8 Innovative leadership (values in management practice)

The essence of innovation

The essence of innovation starts with critical thinking. In the first place, one has to get comfortable with the knowledge that we do not always have the right answer. In fact, in situations where we don’t have the answer, we have an ideal situation for creative innovation. We have to feel comfortable in the gap between what we know and what we don’t know in order to shift into innovation successful y. This refers to a mind-set, as well as a paradigm, as argued earlier. This mind-set is the starting point in our approach to innovation.

We have to investigate what our assumptions are. What we do, what we think, what we dream and

ultimately are able to do, is based on a whole set of assumptions. These include, for example, the functioning of reality, the client, the market, the product, and the role and purpose of innovation. There are no right answers in innovation and there are no right answers in our assumptions. It becomes a practice of asking questions. Crucial y, the right question is more important than the right answer.

At the very beginning of any creativity process or any innovation process one has to start dreaming. The essence of innovation is to be able to discover what does not yet exist and what would contribute a certain value to society. If one does not want to be limited by any earthly limitation, we can only conceive such an innovation in a dream world. Very often, the limitations of innovations, or the fact that innovations eventual y do not appear to be very innovative, start already in the face of dreaming. One has to dream big. Limitations can come later. But dreaming as big as possible is the correct start for any innovation. In order to go from dream to reality there are many different routes. Some of the most common are: deduction, causation, induction and analogical reasoning.

Next we are invited to think in “full color”. Thinking in full color means to see into the issue from different angles, different perspectives, and different possibilities. One should learn to work around decisions from multiple and very often conflicting perspectives. An innovative leader needs to learn to build his or her judgment in paradoxes. The issue is not to solve paradoxes; the issue is to accept them and to live comfortably within the paradoxes. We need to accept these paradoxes in order to be able to move the company into a higher level of integration, a higher level of awareness, a higher level of consciousness, as discussed earlier.

What does it mean to think creatively and innovatively? In many cases, we have to start by analyzing large volumes of ambiguous data. If we want to be in the innovation space we do not have clear, correct and interpretation-free data. Correct and relevant information does not always exist within the innovation space where we wish to work. We are referring to real innovation, meaning “what is not yet there”, and hence the data cannot be there yet either. The next step would be to frame the problem. In the face of dreaming and dreaming big, we have to keep possibilities open as far as we can. However, and there are techniques for doing this, at a certain point in time we will have to frame problems. One cannot innovate within an infinite space of opportunities.

Ultimately, we have to create infectious action, and that infectious action should be based on design principles. A few headlines of design principles are the following: Where possible, we should try and use teams that are as diverse as possible. The easiest and best way to use design principles is to work on well-defined projects. We have to acquire an approach of emerging problem solving. During the process of design we should have a number of cycles of doing, debriefing and learning. Innovation means trying to fail as rapidly as is feasible, learning and correcting the failure. But trying to fail fast, of course, goes against the idea of failure avoidance which we all natural y prefer to do. We would have to be brave and make a mental shift towards accepting failure as a learning tool and not a measurement of competency. Any prototype should be tested vigorously. The entire process should also be run and managed correctly. Too many innovation projects fail due to poor project management.

The innovative individual

Now, based on current research findings, let us investigate a few of the qualities of the innovative individual. The innovative individual is relentlessly curious. Curiosity is the basis of most innovation. Being an individual that is curious is of course something which is more of a quality, a mind-set, than something that can be trained. An innovative individual equal y needs to be passionate and enthusiastic. The road to innovation is not always an easy one and therefore a great deal of energy, enthusiasm and perseverance is crucial to succeed on the path towards innovation. Furthermore, if one is not passionate about the concept, or the project, or the dream we’d like to realize, the chances of realizing that dream are limited. The individual who wishes to become a great innovator has to be tenacious. Innovation takes time, effort and energy, and it will not always be an easy road. An innovative leader, of course, equal y needs to be a very creative person. That creativity might show up very often as a capacity for visualization. Training in visualization is therefore indispensable to support innovation. When talking about creative potential, we therefore could include a capacity of visualization into the creative arts, but that is not essential.

An innovator also needs to be interested in the ability to discover which, amongst others, is linked with the capacity to associate. We have to be able to collect ideas and, in particular, to look elsewhere for those ideas. Many of the most useful new ideas will not be found in the immediate vicinity of the problem. One has to question and observe and have an attitude of questioning everything. Inventions like the Apple Mac are based on questioning the need for a fan in a PC, which at the time were big and noisy. Simple but profound questioning can lead to breakthrough inventions. An interesting tool for doing so could be the use of metaphors. Metaphors allow speaking without getting caught up in the details of the operations.

Simple, but profound questions might also help. What is…? What caused…? Why and why not…? What if…? Those questions might lead us to look for better ways of doing what we think should be done.

A difficult yet crucial activity is to become as intimate as possible with the client. In the section on techniques we will deal with some techniques for doing this. Only if we get a clear and “intimate” understanding of the needs of the client, can we use innovation to fulfill those needs. A starting point might be to look for anomalies. Whilst looking into what is taking place, pay attention to observing with all the senses. Be aware and develop a deep awareness.

Do all this within a network of people. Surrounded by people you might get bright ideas from those that are with you on the journey. For the same reason, use outside experts.

Final y, experiment. Cross physical boundaries and cross intellectual boundaries. Innovations will probably be found where others have not yet been looking.

One of many possible tools to test your “Innovator’s DNA” can be found on www.innovatorsDNA.com.

Give it a try.

The Innovative team

When discussing the innovative team we consider people (the innovative leader, the innovative team members), processes – which we will address later – and a philosophy. In order to establish innovation I would like to suggest the following philosophy: Innovation is the job of everyone in the company, not just of those earmarked to take responsibility for innovation. Disruptive innovation is an equal part of our innovation portfolio. Not all innovation should be disruptive, but it is an important part of the overal portfolio and should receive adequate attention. I believe that an innovative approach that has the most chance for success is one where we deploy multiple smal , properly organized and agile innovation project teams. Those teams should take smart risks. Without taking risks innovation will most likely not happen. However, risks should be seriously considered with a deep knowledge of, and intimacy with the customer.

Teams should ideal y be practical y diverse. Some degrees of diversity might, indeed at first, appear to be counterproductive, but overall it appears that high degrees of diversity pay off in creativity and innovation. Last but not least, an important credo for such teams is to have fun together. Innovation is not only hard work. It should be properly organized, teams should make sense, and the project management should be effective, but it is the fun, the playfulness and the creativity that will be important drivers for innovation.

From a process point of view, a number of processes have proven successful in the past. Further in this chapter, we are going to mention a few techniques, and at the end of the chapter we are going to suggest a specific approach: the Innovation Road Book culminating further in the Cassandra tool. The companion website to this book www.innovationroadbook.com also contains some further reading and information.

Innovative leadership

Innovative leadership has a lot to do with leadership per se, and therefore we refer to the previous chapter, dealing with leadership within this inclusive paradigm. Bringing this closer to innovation, innovative leadership will equal y need a vision. We need to agree on where we would like to go. Without a vision it is very difficult to take any relevant decision. Without a vision, any decision is a good one. Referring back to Alice in Wonderland, I would like to paraphrase the cat. When Alice asks the cat which road to take, the cat asks Alice in turn where she would like to go. When Alice replies that she doesn’t real y know, the cat appropriately replies that if you don’t know where you would like to go, then any road is a good road. This may be fine if you’re Alice in Wonderland but it could be problematic when there is more at stake? In other words, it may not be that important to have a vision in order to work towards real innovation, but in the absence of a vision, it is impossible to take an informed decision right now.

An innovative leader should not be fearful of failure. Failure is an important part of innovation. Without failure, not much learning takes place. Learning is indeed easier in the case of failure. One should not promote failure, but accept it and gain learning from it. An innovative leader should equal y be able to manage conflict. Teams, and specifical y diverse teams, might have high degrees of opposite views, crucial for evolution, but not always easy to manage. In line with this, the innovative leader should also be able to manage diverse agendas. Innovation is not only limited to brand new products or developments. It is equal y a dynamic process of improvements fitting current corporate or departmental agendas.

At a certain point in time, a leader needs to commit resources at the right time, the right amount and for the right purpose. Innovation does need investment and it is always a visionary decision to match the need to the possibility.

Last but not least, innovative leaders are certainly not process optimizers. Though project management should be done correctly, an innovative leader has a different focus, capacity and drive.

Innovation techniques

A number of innovation techniques are available, and have been applied with more or less success. We would like to run through a few of them here.

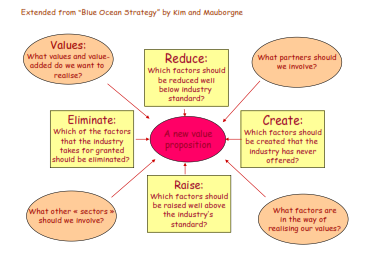

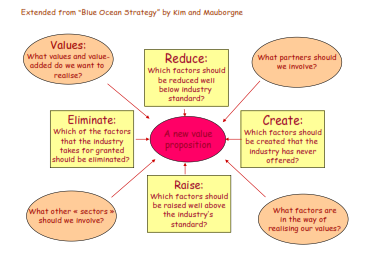

The first one, that I will describe further, is an extended version of what is known as the Blue Ocean Strategy. The Blue Ocean Strategy has been a successful book, suggesting a framework in order to be able to identify Blue Oceans for a company (as opposed to Red Oceans of competition), where a company should be able to thrive. Though in the short term, this no doubt makes sense, in the longer term there is no reason why a Blue Ocean would not become a Red one of competition. However, the model used for the analysis is an interesting one, particularly in order to analyze what to do in order to go from the current to a desired state. Whenever this situation presents itself, this model could be used (see further under the Innovation Road Book).

• Another interesting and useful model is the “Business Model Canvas” of Osterwalder and Pigneur (Wiley, 2010). This model helps us with business model generation. It requires detailed thought for a number of relevant elements of a business model. The model questions areKey partners to the innovation (or the company or project)

• Key activities (the transformation that is taking place)

• Key resources (what is necessary)

• Value proposition (what value is created and where does this value go)

• Customer relationship (relates to the intimacy discussed earlier)

• Channels (of distribution)

• Customer segments (some creativity is required here)

• Cost structures

• Revenue streams

Particularly in respect to customer intimacy, the authors propose a few questions, which they label as

“The Empathy Map”. The questions raised are, in respect to the customer:

• What does she think and feel? What real y counts for her? What are her major preoccupations? What are her worries and aspirations?

• What does she see (senses)? Who are her friends? What is her environment? What does she see (sensorial intake) that the market offers?

• What does she say and do? What is her attitude in public, her appearance, her behaviour towards others?

• What does she hear? What do her friends say, and what does her boss say? What do other influencers say? And who are those influencers?

• What pain does she have? What fears, what frustrations and what obstacles does she see? • What gains can she see? What are her wants, her needs, and how does she measure her success?

Again, to help with the transition from the current to the new, you could either use the Extended Blue Ocean Model or more profoundly, the Cassandra tool described in the next chapter.

We have a long list of techniques and approaches that might be useful in innovation thinking, creativity sessions and brainstorming sessions of different kinds. We will list the best known, but it is clear that in order to real y make sense out of them, some practice will be necessary. Some of those tools (like Soft Systems Methodology) are very rich and powerful, but not that easy to apply. It would need a bit of interest and training to get started with them. Most of the techniques will speak for themselves.

Some of these techniques are:

• Soft Systems Methodology (a methodology designed by Checkland, very popular in IS design and political consensus building, focusing on meaning and shared understanding)

• Rapid prototyping

• Reversal techniques. In order to see the consumer as a consumer, could you for a moment assume she would become a producer? The French energy company has successful y introduced solar panels on roofs for individuals to produce their own electricity, but also to sell the overproduction back to the energy company. By doing so, the energy company has been able to, with lots of small investments, rapidly build a high performing solar network, which they would never have been able to do, on their own.

• Lateral thinking

• Rotating attention. Leave your frame of reference and understanding behind and move into a space of deeper understanding.

• Techniques of direct analogy

• Bisociation (compared to the wider association)

• Subtraction. Take something out of your reasoning that seems crucial: can you imagine a restaurant without food?

• Design for extreme affordability. Can you imagine a (child) incubator without electricity? Can you imagine a refrigerator without electricity?

• Tell a story to “blind” people, and look for their perspective

• Ideation. Come up with a funnel of ideas: the normal ones, the crazy ones, the impossible ones, etc.

• Visual thinking (using visual techniques)

• Story telling

• Scenario building

All of those have successful y been applied in isolation and in a broader methodology (like the Innovation Road Book).

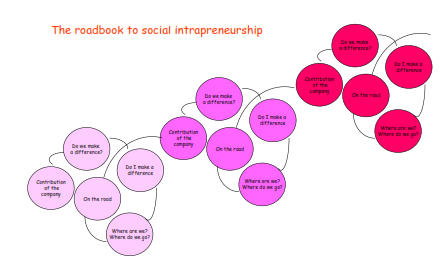

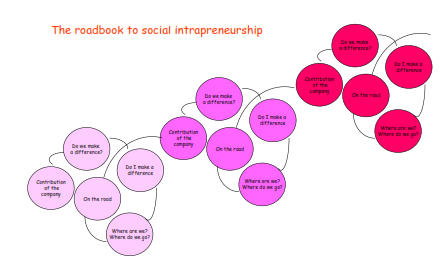

An experience-based methodology for innovative leadership: The Innovation Road Book

In this section of the chapter we suggest a possible approach, a methodology, to take on, and execute leadership in innovation. Obviously the method suggested fits the paradigm shift proposed in this book, and it equal y incorporates a number of questions and questionnaires that have been introduced earlier in the book. The ultimate tool – Cassandra – a tool with somewhat broader application than a purely innovation perspective, will be detailed further in the last chapter of the book. Cassandra is an audit and management tool that allows the manager to audit and analyze a company or a situation from a systemic point of view. It allows for the design of a change agenda, both on a personal level (the personal version) and on corporate level. More interesting, though, is to have both levels together, based on the same tool, within the same innovative paradigm.

The Innovation Road Book is focused on innovation per se, and could be used with or without Cassandra as a final overall systemic change management analysis, leading into a particular change agenda.

This section proposes how to operationalize some concepts developed in the book, in particular related to the innovation part of it. It offers a set of checklists and questionnaires – discussed in earlier chapters – which, together, act as a roadmap to innovation leadership. This roadmap is available for use, either as a step plan for implementing innovation, or alternatively for benchmarking one’s own potential in comparison with other companies. However, in order to use it to its full potential, either training or tutoring might be necessary. The checklists indeed fit a wider concept (as the book argues in depth) and, without a thorough understanding of this concept, the checklists themselves will be less effective and have less impact.

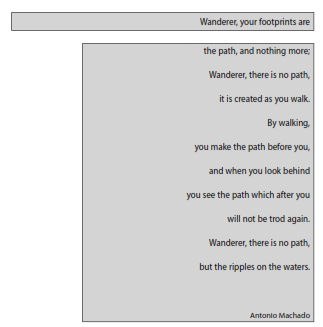

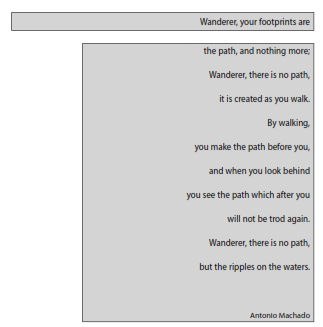

These methodologies form a continuous loop of evaluation, designing, laying down the path by walking (Machado), learning, re-evaluation, re-designing, etc. The remainder of this appendix will mainly focus on assembling a number of checklists and tools that together make up the roadmap.

The values and the vision: what is the contribution of the company?

Values-based innovation starts in the right lower quadrant of Wilber’s systemic model, i.e. with the identification of the (shared) values. Since they very often remain hidden or unknown, and since they are the drivers of the sustainable performance process, the first step involves making them explicit and discussing how far they are shared. Why try to answer the question of what the values of the company are and/or what it contributes to society? If the company would no longer exist, what would society miss? If the creation of employment would be a value for a company, then bankruptcy would certainly cause a loss of value. However, this would imply that the creation of jobs would be a core value of the company (and not a necessary resource constraint). Values-based leadership will be driven by those shared values.

The first stage might start from a very exhaustive list of possible values purely to make it easy for people to start choosing. In the second stage, those values will be negotiated in order to find out what the shared values are. Once these are agreed upon, they can be translated into personal development issues like leadership and learning.

Though this is the first crucial step in the Innovation Road Book approach, we are not going to re-discuss this here. We refer to the chapter on values and the checklists in order to facilitate this important first step.

As discussed earlier, Buckingham and Coffman’s studies of organizational effectiveness produced the following interesting checklist. Exceptional leaders need to create exceptional workplaces where innovation can real y foster. According to them, exceptional managers create a workplace in which employees emphatical y answered ‘yes’ to the following questions (and relate them to the innovation climate and approach in the company):

13. Do I know what is expected of me at work?

14. Do I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work right?

15. At work, do I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day?

16. In the last seven days, have I received recognition or praise for doing good work?

17. Does my supervisor, or someone at work, seem to care about me as a person?

18. Is there someone at work who encourages my development?

19. At work, do my opinions seem to count?

20. Does the mission/purpose of my company make me feel my job is important?

21. Are my co-workers committed to doing high-quality work?

22. Do I have a best friend at work?

23. In the last six months, has someone at work talked to me about my progress?

24. This last year, have I had opportunities at work to learn and grow?

And again, the number of “yes” responses gives you an idea of the organizational effectiveness, or the degree in which employees and managers feel supported by the company in their endeavour to realise an innovation culture.

Benchmarking: from dream to reality (do we make a difference?)

Imagine an organization that has been able to identify values or the anticipated value-add of its existence or activity. The next step in our continuing journey is to establish some kind of benchmark. Compared to other companies, activities or industries, does the organization deliver something that is not yet delivered elsewhere? Can a number of elements, which would give a certain concrete idea of the direction to follow, be identified? Would they real y be different and capable of forming the industry standard? This kind of benchmarking is not for competitive reasons, not for finding blue ocean strategies (as in Kim and Mauborgne, 2005), but for helping to identify the things that make a real difference, both in a detailed and simple fashion. It is this analysis that will help enable our marketing support, our commercial argumentation, our commercial message, etc. It is going to help to translate values, mission and value-added into communication (internal, as well as external).

In a two step procedure, the first makes a rather classical benchmark analysis. The second attempts to evaluate the innovative potential. Is it possible to ensure that what is offered is a real innovation (rather than just a copy of an existing product or service)? Does the proposal have the potential to innovate the market, the industry and to make a social difference? In aspiring to this new development what resources are needed?

For the first step, we base our analysis on an extended version of Kim and Mauborgne’s (2005) blue ocean concept. For the second step we use part of an innovation roadmap methodology (designed earlier within the innovative learning-by-doing platform, for practising managers to learn about management while creating and managing; captured under the framework called Free For All). The roadmap itself contains more steps than the ones used here, but these are restricted to the most essential ones that fit the methodology proposed in this chapter.

The first step is based on the following figure that is itself based on the blue ocean concept. The blue ocean strategy invites a company to develop products and services that tap into a blue ocean (an ocean without fierce competition, compared to a red ocean of “bloody” competition). The approach proposes to ask the following four questions:

1. Which factors that the industry takes for granted should be eliminated?

2. Which factors should be raised well above the industry’s standard?

3. Which factors should be reduced well below the industry’s standard?

4. Which factors should be created that the industry did not previously offer?

The answers to those questions give an idea of how the company, new product or whatever else positions itself in the market. Equal y, the answers, especial y to the fourth question, give an initial indication of the innovative potential of the company, service, etc. Though these factors can be identified individual y, this is typical y an exercise done in an animated workshop, since some of the questions might be rather challenging.

But we want to expand the blue ocean approach with an additional four questions that position the company (or its new product or service) within a broader network (of partners), related to the specific purpose of realizing values, and demand a more intense and varied innovation focus:

• What values and valued added do we want to realise, compared to what exists (at this time)?

• What factors are in the way of realizing those values?

• What partners (companies, organizations) should we involve?

• What other “sectors” should we involve in our activities?

It is worth recalling that one of the remarkable observations in social entrepreneurship is that companies and services are often not limited to one specific sector or industry. The (social) business model innovation advocated here, aims to realize the same openness to others and to enrol solutions into a holistic focus on the value-added of the company (that will be reinforced by the use of Cassandra later on).

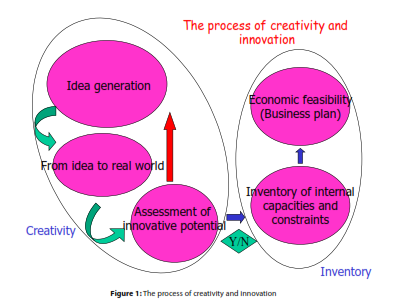

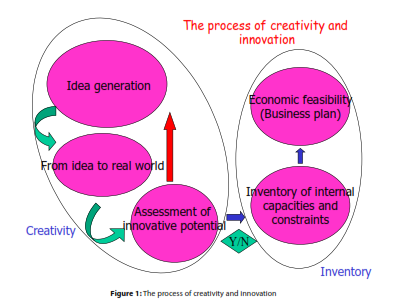

The road book approach

In the overall innovation literature, a rather clear distinction is made between the phase of creativity and the follow-up phase that is commonly addressed as the innovation phase, the phase of creation (detailed planning and production). The first phase receives low priority in innovation literature, though most literature also agrees that success and failure of new product development is often already ‘genetical y imprinted’ at the start of the so called innovation process, based on the quality of the creativity phase. A second, well identified reason for failure can be found in the process of the creation phase. What we call an innovative project in our Masters in Business Innovation and Intrapreneurship (MBI&I) clearly contain both aspects. Where we certainly stress the importance in time and effort spent on the first creativity phase, we do require at least an inventory of the resources and limitations to overcome, for the creation phase.

Based on what common theories suggest, an innovation process, the way we have described it, contains roughly 5 different phases:

• Idea generation

• From idea to real world (how to translate an idea into a concept that can be communicated)

• Assessment of the innovative potential (annex the commercial feasibility) of the project

• Inventory of the internal capacities and constraints in order to assess technical feasibility

• The economic (and mainly financial) feasibility: the business plan

Though a certain progression in time seems logical, certainly in the first three phases some feedback loops will prove to be necessary and extremely beneficial in adding value. However, at a certain point in time and after a number of feedback loops, one should continue into the development phase and the economic viability study. The following diagram il ustrates the process which we will detail with the help of some checklists and relevant issues/questions further on in this document.

Based on the figure above, the innovation process starts with an idea-generation and/or creativity phase. This is the phase in which the wildest dreams are transformed into ideas. Very often, this process gains influence if it can be undertaken in creative groups (rather than by creative individuals).

Frequently a difficult step is to translate ideas into the real world. The idea is clear in the mind of the idea-owner(s), but then needs to be translated into a form that can be communicated to a wider audience. That is not a typical problem for the innovation process, but successful y overcoming it is of paramount importance and key for further successful development. In order to support you in this key step, we offer some ideas of soft systems methodology (SSM) which is a methodology designed to transform ideas into the real world, with the aim is to eventual y design Information Systems. In the MBI&I program, a workshop on SSM and action learning is scheduled, but the main concepts can already be practiced here.

Once the idea is translated from the owner’s mind into a form that can be communicated (with sentences, activities, to-do lists), it is useful to assess its innovative potential. It is difficult to evaluate the innovative potential of an idea if it is not, to some extent, expressed on paper. Therefore, this step can only be undertaken after the ‘translation from idea into activities’.

The logical consequence from idea generation, via translation into a communicative action description in order to evaluate its innovative potential, is a cycle that does not necessarily immediately generate the eye-catching new product or service. Here a likely feedback-loop probably brings you back to the phase of idea generation. Creativity and innovation is very often a process of incremental steps, rather than earth