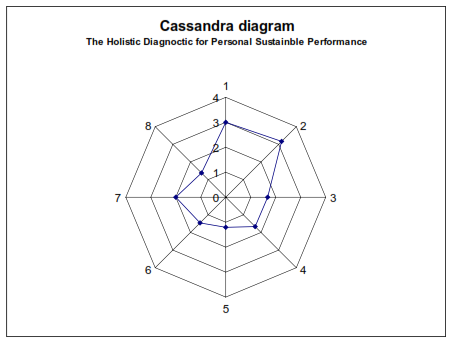

9 Relevance (The concept of the Cassandra tool)

Some Tibetans believe our present world of war, disease, corrupt

inequality and environmental desecration, is the self-destructive

age of Kali, to be fol owed by a new age of peace, ethnic harmony,

environmental balance, and human dignity, yet to come. This future

is Shambhala, sometimes cal ed Shangri-la.

(Laurence Brahm)

Reckless growth, growth for the creation of shareholder value, is increasingly questioned. Or at least, the consequences are. Oil prices are skyrocketing, not only due to an ever-growing demand of oil, but also demand from the emerging economies. We cannot reasonably criticize them since it is our economic model that has created the dream of unlimited growth. However, that same drive for growth is likely to cause economic depression through its recklessness. When this was published in our previous book (Baets and Oldenboom, 2009), at the time of writing, we were not yet in the world crisis that broke out in 2008.

This book has developed an understanding of business thinking and how it could, and should, be rethought. It has defined a number of fairly new managerial concepts, like management by values, co-creation, sustainable performance and sustainability. Above al , it aims to present a coherent new management paradigm, a systemic management paradigm. This paradigm is, on the one hand, embedded in the latest scientific developments and, on the other hand creates space for concepts like corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. It also gives managers the framework within which they are not only able to develop responsibility, but also to make responsibility an important component of sustainable performance. With a systemic approach, as argued in previous chapters, sustainable performance supersedes financial performance.

However, in order to support managers who are willing to make this paradigm shift, there is a need for a methodology – a set of tools that fits the stakeholder paradigm of management. In the appendix we suggest a blueprint for a roadmap: a methodology and a number of checklists. These are designed to help managers to get the process started, to support co-workers, and to give tools for continuous monitoring. The roadmap adopts a very down-to-earth approach to assist managers who have opted for the paradigm shift, with starting the change process.

A real paradigm shift in a company, and a relevant managerial approach that fits this new paradigm, is indeed a major change project. We do not want to repeat here all that has been written on change processes. However, the first step of this change process is the manager’s paradigm shift, since it is his or her belief in this new paradigm that will become the driver of the change process. This belief, this view, this energy, this meaning, which the manager aims to give the company, becomes the heartbeat of the company. The appendix only gives a number of tools, but it does not replace the necessary change process – they are only the supporting tools. Inappropriate use of this appendix, and in particular its application without the paradigmatic context, might make the tools useless and even counterproductive. A company interested in this shift, a shift towards responsible management (corporate and individual) that, by definition, wil be sustainable (see the Ben Eli definition), aims at sustainable performance. Sustainable performance, in turn, targets fulfillment of all the stakeholder interests, and is a learning and change process that most often needs some support and coaching. The methodology described here is able to give that support, provided that a well-trained consultant-coach (trained in the Cassandra approach) coaches this process.

Laurence Brahm has noted a parallel shift in the world of spirit in noting how some “Tibetans believe our present world of war, disease, corrupt inequality and environmental desecration, is the self-destructive age of Kali, to be followed by a new age of peace, ethnic harmony, environmental balance, and human dignity, yet to come. This future is Shambhala, sometimes called Shangri-la.” This chapter is not that concerned with such a meta-theoretical perspective but rather with the role of business in the world. Accordingly, the focus is on social intrapreneurship which, in parallel with social entrepreneurship, re-valorizes the creator, the innovator and the entrepreneur in the manager (instead of the administrator). It aims to make a concrete contribution to society and to realize one or more values. Social intrapreneurship has to do with creation, innovation, learning and making a difference, but always with the purpose of adding value to the stakeholders at large and society. The world would miss a social intrapreneur if he or she would no longer be there. The social intrapreneur makes a difference, not only for the shareholders, but also for all the stakeholders, and for the environment of the company.

Although already suggested, it is worth saying a last time explicitly: Social intrapreneurship, managing for sustainable performance and social responsibility need a new paradigm. This book’s project differs from other books around social and environmental responsibility and the like, in two distinct ways. Firstly, it puts al those concepts into the framework of a new paradigm, and secondly, it clarifies that that paradigm shift is the single most important move to make. The rest follows automatical y. The mainstream paradigm does not allow mental and financial space for sustainable development or responsible management. Without the shift, responsibility and sustainable development will ultimately end up in the mainstream paradigm as marketing actions, or to put it crudely: corporations are doing no more than attempting to say “look how good and kind we are; we have programs on social responsibility and we deal in fair trade products”. Despite the rhetoric and relatively marginal actions, their baseline remains the same. And it is this devastating baseline that eventual y, over the long term, makes responsibility in management and sustainable development impossible. The concept of sustainable performance cannot co-exist peaceful y with the mainstream paradigm.

This can be clarified in more detail through Draper et al’s “Key hallmarks list of a business leader” and, especial y, the following “Memorandum of the social innovator” on the necessary qualities.

• A genuine commitment to contributing value to the economy and the society is visible at the highest level of the business, with values and sustainability principles present in core strategic goals.

• There is a clear vision of the organization in a future (a long term view) where sustainability is core to creating value.

• Key sustainable performance indicators are fully integrated into the governance system of the business.

• Staff are encouraged to deliver the sustainability program through effective performance management, incentives and provision of appropriate tools and resources.

• Future products and services will deliver value to society, sustainability and profits.

• Marketing campaigns and pricing structures help customers make more sustainable choices. Transparency is a key value.

• Close partnerships with suppliers are in place which improve standards and stimulate innovation.

• The environmental impacts (and the stakeholder impact) of the business, both direct and indirect, are well understood.

• The business has a clear understanding of what it would mean to operate within environmental limits.

• There is clear comprehension of the value of stakeholder engagement.

• Stakeholders are involved in identifying and prioritizing material issues, as well as values of the company at a strategic level.

• The business demonstrates consistency on public messages and ‘behind the scenes’ lobbying, with policy proposals reflecting policies and commitments on sustainability and transparency.

• Progressive government action towards a higher degree of sustainability is sought at a national and international level.

• Business risks and opportunities associated with sustainable development are well understood and communicated.

• Environmental and social cost accounting methodologies are recognized and understood by investors and used in describing material realities.

• Community activities have strong links to the core business, its brands and its products/ services.

• Reporting focuses on material issues, and the system for prioritizing these is robust and transparent. The organization doesn’t shy away from difficult and sensitive issues.

• The report forms an integral part of management systems, driving performance, engaging stakeholders, and challenging the industry.

The five shifts required to facilitate the development of sustainable performance in business are:

Shift 1: Take up of a systemic view of the company by the mainstream

Shift 2: Promote the sustainable performance business model

Shift 3: Valorize the intrapreneur in the manager

Shift 4: Accept that whatever is done should have value for society

Shift 5: Re-engineer the metrics of business

If the reader moral y subscribes to this memorandum, the time is ripe for a managerial paradigm shift.

The methodology

The appendix proposes how to operationalize the concepts developed in the book. It offers a set of checklists and questionnaires – discussed in earlier chapters – which, together, act as a kind of roadmap to sustainable performance. This roadmap is available for use either as a step-plan for implementing social intrapreneurship, or alternatively for benchmarking one’s own performance, or sustainable performance, in comparison with other companies. However, in order to use it to its full potential, either training or tutoring is necessary. The checklists indeed fit a wider concept (as the book argues in depth) and, without a thorough understanding of this concept, these checklists will be less effective and have less impact.

The Cassandra methodology has five constituent components:

1. The values and the vision: what is the contribution of the company?

2. Benchmarking: from dream to reality (do “we” make a difference?)

3. The leadership’s checklist: do “I” make a difference?

4. Cassandra: a diagnostic for sustainable performance (where are we and where to go from here)

5. The learning coach: continuous work on the mutual selves (“on the road”)

Those five constituent components form a continuous loop of evaluation, designing, laying down the path by walking (Machado), learning, re-evaluation, re-designing, etc. The appendix itself mainly focuses on assembling a number of checklists and tools that together make up the roadmap.

The main tool we propose is named “Cassandra©”. In Greek mythology, Cassandra (‘she who entangles men’) was a daughter of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, and her beauty caused Apollo to grant her the gift of prophecy (or, more correctly, prescience). However, when she did not return his love, Apollo placed a curse on her so that no one would ever believe her predictions (Wikipedia). This metaphor could hardly be more il ustrative for introducing this shift in paradigm.

Sustainable performance, though it seems to speak for itself, is yet another unknown concept. Unable to find a definition for sustainable performance – rather bizarre in a world filled with discourse about sustainability and responsibility – this chapter offers one. Based on Ben-Eli’s core principles, sustainable performance is corporate (or organizational) performance that seeks a dynamic equilibrium in the

processes of interaction between a company, the carrying capacity of its stakeholders, and the environment in such a way that the company develops to express its full potential without adversely and irreversibly affecting the carrying capacity of the stakeholders and the environment upon which it depends. As previously argued, this rather new concept needs another context and paradigm but, for application, it also needs metrics.

Cassandra: a holistic diagnostic for sustainable performance and personal development

Within the framework of this book, sustainability, sustainable development, sustainable performance and corporate responsibility, only find a conceptual basis within a holistic view on management. Within classic managerial approaches, other than for personal (or corporate) ethical motivation, there is no reason or space for a company to be responsible or sustainable. The President of the EFMD correctly iterated during the Global Compact Summit in Geneva that the average manager does not automatical y think in terms of “responsibility”, so if that is to be changed there is a long way to go. This book does not necessarily stress the length of the journey, but rather the taking of different routes. A highly reductionist view on management, focusing primarily, if not exclusively, on short term financial performance, makes sustainability counterproductive. There are no commonly accepted managerial theories that give the manager tools for managing differently.

Some will argue that economics allows for the accounting of any externalities by including, for instance, the cost of pol ution. There needs to be a clear distinction between the economic calculations of costs for certain externalities and straightforward management of sustainable development. Calculation of costs for externalities that in fact turn them into an economic good, and allowing them to be traded off, is no solution for sustainable development. It simply shifts the costs of economic development from those with economic power to those without economic power, and at the same time keeps that economic development concentrated in the hands of the economical y developed. The market for CO2 emissions is only one example and resembles the active trade of risky country debt a number of years ago. Indeed a number of international banks have been able to make money on selling high-risk loans, without at any point solving the problem of that same towering country debt. Sustainable development cannot be seen other than within the large network of countries and individuals that are all equal y a part of planet Earth. We all have to move forward in co-creation, within a holistic perspective. In certain aspects, it becomes a zero sum game. Sustainable performance and management for sustainable performance therefore needs both new concepts and new diagnostics.

This chapter outlines the development of a diagnostic based on the Wilber holistic model, but adapted to a managerial context. For each of Wilber’s quadrants, we identify, with reference to existing management research, a number of items that together co-construct the quadrant. The diagnostic is primarily an inventory and can be further used as a guide for transforming a manager into someone who is capable and prepared for a different way of management. At a later point the book will develop it as a management tool. At this point, the focus is on the manager as a person; the person who is going to be the transformational leader able to manage his or her company or organization, for sustainable performance. The diagnostic analyzes the individual’s potential for sustainable managerial performance and is, in fact, a tool for personal development.

The manager scores each question on a 1 to 5 scale of agree/disagree or yes/no. It is clear that not all the questions are equal y easy to understand and can be interpreted differently. This tool is used more adequately (and more easily) within a coached framework, but has been successful y tested for non-guided use. High quality coaching and tutoring will always improve its learning potential.

The holistic management quadrants were labeled: values; personal development; mechanistic approaches; and holistic systemic approaches. For the purpose of the development of a diagnostic, we have subdivided each quadrant in two items and we have given the content more of a performance orientation.

The value quadrant is subdivided into the themes of “diversity” and “complexity”. Based on the work of de Anca and Vazquez (2007) and Kofman (2006), the diversity theme has been covered by the following questions:

• Do you base your actions on ethical codes?

• Do you sometimes reflect on the sustainability of your actions?

• Do you pay attention to being anti-discriminatory?

• Do your actions reflect Social Responsibility?

• Do we need to take care of all the parties involved in what we do?

• Is assessing someone’s work environment important?

• In an organization is it important to pay attention to retention of talent?

• Do you believe that a variety in opinions is a value?

• Do you pay attention to communicating effectively with those around you?

• Should leadership be strongly committed?

• Do you see active interest groups as an asset for society?

The questions for the complexity theme are based on the findings of our own earlier work (Baets, 2006):

• Are you most dynamic and creative at the edge of chaos?

• Does evolution need both the new and extinction?

• Is diversity a prerequisite for the emergence of the new?

• Is radical unpredictability an essential characteristic of any organization?

• Is the self-organizational capacity of any group an indicator for sustainability?

• Is interaction between “individual agents” essential for self-organization?

• Is agency (the action) located at the level of interacting individual entities?

The personal development quadrant is subdivided into the themes of “personal wel being” and “leadership and teamwork”. The first theme questions the undeniable link between wel being, happiness in one’s job and the person’s contribution to the development of the company. The analysis is based on the work of Chopra (amongst others, his simple guidelines published in 1994), who is an authority on mind-body medical approaches, and retains the following questions:

• Do I value an active approach for the development of individual competencies and skil s? • Do I also value time which is not immediately productive?

• Do I practice a policy of non-judgment on appearances (facts, humans, etc.)?

• Is joy an active element of my professional or societal life?

• Do I feel valued in my professional environment?

• Do I have real responsibility and the space to maneuver?

• Is there space for the realization of my desires in my function/activity?

• Is courage valued in my professional environment?

• Do I feel an essential part of the whole?

The theme of leadership and teamwork is plugged into an alternative source. As discussed in Chapter 7, a number of years ago, Roger Nierenberg (1999), a well-known conductor, made a remarkable TV program in which he put managers in-between the BBC orchestra members in order to have them experience

the essence of leadership and teamwork. He conducted small exercises with some of the managers and the orchestra and, while doing so, dealt in a brilliant metaphorical way with the essentials of leadership and teamwork. The questions retained for this theme are:

• Is each individual (surrounding me) well trained and prepared to do his/her job?

• Is a constant sense of awareness essential for success?

• Is my professional environment an intense network of communication?

• Is the purpose in my professional environment always clear and shared?

• Do my managers create space for others?

• Are my managers more concerned with projecting a vision and less with correcting what happened previously?

• Does rigid leadership create confusion?

• Does lack of clarity cause tension and under-performance?

• Do I have an external focus that gives meaning to my work?

The two so-called external quadrants are more classic and better known by most managers. The mechanistic performance has been subdivided into “financial performance” and “innovative potential”. Financial performance is not expressed in absolute figures, but rather in comparison with the perceived peer group, and accepts that the financial performance of a person is highly dependent on what he or she perceives to be wealth and a “correct” financial situation. The basic variables are based on Stone’s work (1999) and the questions retained are:

• Is my appreciation of my revenue above average in society?

• Is my appreciation of my belongings above average in our society?

• Is my liquidity position above average in society (can I buy what I real y want)?

• Do I generate enough cash in order to be financial y self-sufficient for what I want to develop?

• Does my cash-flow generation give me a feeling of comfort?

Anticipating that over a certain period of time (this is a longer term diagnostic) the capacity to create and to innovate is essential for performance, the second component of the mechanistic performance quadrant is one’s potential to innovate. This is based on innovative potential from the theories of Edward de Bono (as they are commercialized though a network of consultants). In this case, the questions are based on the work of Advanced Practical Thinking Training Inc. (2001).

• Do I actively pay attention to developing new ideas?

• Am I am able to produce creativity on demand?

• Does my professional environment regard idea generation as a key business practice?

• Do I personal y develop new ideas on a regular basis?

• Does our leadership structure acknowledge innovative thinking?

• Should an organization have a structured process for evaluating/refining new ideas?

• Does our professional culture value idea assessment/refinement as a core competence?

The final quadrant focuses on systemic performance. Its themes relate directly to systemic concepts of performance such as sustainable development, social responsibility, knowledge management, and organizational learning. As established earlier in the book in more detail, those systemic themes are an essential contribution to sustainable performance and therefore need to be present in a holistic diagnostic. The sustainable development and social responsibility questions are based on the work of Stacey (2000), one of the forerunners in linking strategy with complexity to deal with a complex world.

• Do I value unconditional responsibility?

• Do I value essential integrity?

• Do I value ontological humility (is my basic starting point to be humble)?

• Do I value authentic communication?

• Do I value constructive negotiation?

• Do I value impeccable coordination?

• Do I value conscious responses?

• Do I value emotional mastery?

For the knowledge management and management learning theme, the questions are based on Baets and Van der Linden (2000), where the background of the questions is analyzed in detail.

• Should project managers use more than financial factors to measure success?

• Does the rigidity of processes give people very little possibility for correction?

• Because interaction is important, is harmony between people crucial?

• Are confidence and control two contrary variables?

• Do confidence and motivation have a strong influence on exchange and the creation of knowledge?

• Must confidence levels always be built?

• Does interaction without knowledge prevent learning?

• Does interaction without confidence and motivation prevent learning?

• Do motivation and organization seem to interact positively?

• Is interaction always necessary for the construction of confidence?

• If there are agents at group level who do not cooperate, does the learning of the group stop?

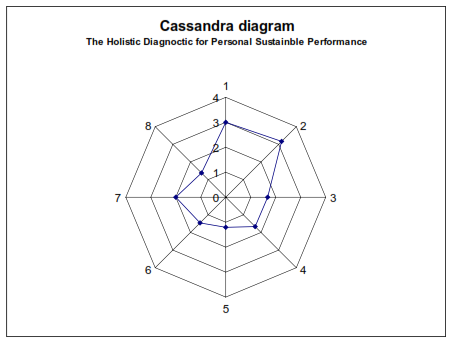

As indicated before, in the Cassandra test the person scores all these questions on a scale of 1 to 5, according to the best of his or her perception. The more honest the answers, the more value the tool will add. The questions are not made in order to be a perfect research tool (though, as explained further, it is correctly tested and validated), but rather to be a good diagnostic. Above al , it is a tool that helps the person develop. In practice this means that the questions are formulated in such a way that ideal y someone would want to have an average value of 5 on all the axes. Of course, this situation is idealized and not realistic, but it provides an actionable picture of the themes that need further attention and/or development. An average score per theme is calculated and a raster diagram represents the eight axes, as in the following il ustrative figure of a possible case.

Values

Axis 1: Diversity

Axis 2: Complexity

Personal development

Axis 3: Personal Well Being

Axis 4: Leadership and teamwork

Mechanistic performance

Axis 5: Financial performance

Axis 6: Innovative potential

Holistic performance

Axis 7: Sustainable development and social responsibility

Axis 8: Knowledge and learning

If this person would like improve their sustainable performance in leadership (his or her own functioning as a manager), he or she needs to develop their personality in areas other than the values quadrant. In the future we will possibly be able to identify most types of managers and types of development paths. For the time being, the idea of this diagnostic is to give a rich picture of the current situation and suggest possible paths for improvement.

Cassandra, the holistic diagnostic for personal sustainable performance has been tested for its stability and validity. The next section gives further insight into some of the observations made during the testing. Overal , however, the tool seems to be well understood by the user and more importantly, easily used by them. The future will show how it works as a tool for personal development and guidance.

In order to make sustainability a concept that is practical y usable for the manager, we have created this diagnostic based on our holistic understanding of sustainability. The tool is oriented to the manager/leader as a person. This is the first step: the personal development trajectory of the learning manager. But the same kind of development needs to be made for the company. The elements developed in this chapter need to be applied company-wide, in order to define a way of management that allows the manager to manage according to a more responsible and more sustainable paradigm; one that is oriented towards sustainable performance. This is the task of the second part of this chapter.

Validity test of the personal version

The Cassandra tool (for personal development) has been construct validated. Detail of this validation can be found in Baets and Oldenboom, 2009. As well as being important to test the construct validity, it served also to demonstrate its novelty, both in subject and in approach (the 8 axes, and the relatively high number of questions compared to more classical approaches). While probably more interesting for the researcher, it should comfort the manager that this tool is sound. The structure invited validation using the technique of Factorial Analysis (FA), based on Malhotra (2004), using data collected amongst Master in Management students, who follow a curriculum within a more systemic management concept.

Seen from the classical point of view of validity of tests, the test results were fine, but at the same time they il ustrated how much variance would be lost if it was only limited to a suggested numbers of variables. As argued, and for the reasons discussed, this approach is one of making a picture as diverse as possible, even if that would be less stable from a classic statistical point of view. The conscious option was to prefer richness of information to stability of tests, whatever the latter would mean.

The corporate version of Cassandra

Based on the principles described earlier, a corporate version of Cassandra has been similarly designed. This version depicts the current potential of a company for sustainable performance,