Appendix: Blueprint of a workbook

The methodology

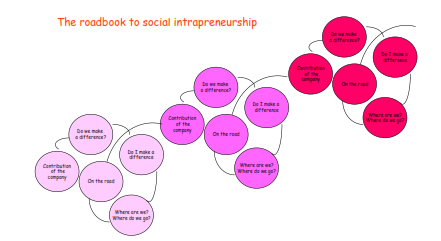

This appendix references and revisits a number of issues and points of discussion from chapters throughout the book and then proposes ways to operationalize the concepts developed throughout the preceding chapters. It offers a set of checklists and questionnaires – discussed in earlier chapters – which, together, act as a kind of roadmap to sustainable performance. This roadmap is available for use, either as a step plan for implementing social intrapreneurship, or alternatively for benchmarking one’s own performance, or the sustainable performance, in comparison with other companies. However, in order to use it to its full potential, either training or tutoring is necessary. The checklists indeed fit a wider concept (as the book argues in depth) and, without a thorough understanding of this concept, the checklists themselves will be less effective and have less impact.

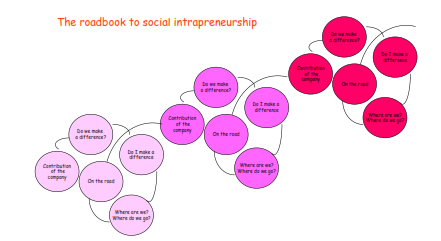

The methodology has five constituent components:

• The values and the vision: what is the contribution of the company?

• Benchmarking: from dream to reality (do we make a difference?)

• The leadership’s checklist: do I make a difference?

• Cassandra: a diagnostic for sustainable performance (where are we and where to go)

• The learning coach: continuous work on the mutual selves (“on the road”)

Those five constituent components form a continuous loop of evaluation, designing, laying down the path by walking (Machado), learning, re-evaluation, re-designing, etc. The remainder of this appendix will mainly focus on assembling a number of checklists and tools that together make up the roadmap.

The values and the vision: what is the contribution of the company?

Sustainable performance starts in the lower right quadrant of Wilber’s systemic model, (i.e. with the identification of the (shared) values). Since, very often, they remain hidden or unknown, and since they are the drivers of the sustainable performance process, the first step involves making them explicit and discussing how far they are shared. It is important to answer the question “What are the values of the company?” and/or “What does it contribute to society?”. If the company would not exist anymore, what would society miss? If the creation of employment would be a value for a company, then bankruptcy would certainly cause a loss of value. However, this would imply that the creation of jobs would be a core value of the company (and not a necessary resource constraint). Sustainable performance will be driven by those shared values.

A first stage might just, in order to make it easy for people to start choosing, start from a very exhaustive list of possible values. In a second stage, those values would be negotiated in order to find out what the shared values are. Once these are agreed, they can be translated into personal development issues like leadership and learning.

It does not take that much of an effort to come up with a whole list of possible corporate values such as: liability, availability of information, involvement, reliability, conflict resolution, consensus, creativity, democratic process, sustainability, ecological awareness, honesty, ethics, organization as a family, decency, shared identity, shared vision, shared values, equal opportunities, community services, harmony, humor/ pleasure, innovation, integrity, quality of living, long term perspective, emphasis on global thinking, nature conservation, humility, mutual support, openness, training possibilities, optimism, personal growth, personal satisfaction, personal freedom, political involvement/activism, recreation possibilities, respect, respect for the law, risk minded, social justice, social cohesion, social responsibility, social security, solidarity, spirituality, strategic alliances, strict moral/religious rules, tolerance, transparency, responsibility, diversity, making a difference, faith, public health and security, prosperity, continuing improvement, peaceful cooperation, friendship, freedom of expression of opinion, conscience of values, world peace, employment and many other values. This list is not in any way presented as exhaustive but as suggestive, and a means to sparking discussion.

Once the real shared values are identified (via an iterative process of workshops or brainstorm session), the next stage is to start questioning how they can be translated into the necessity for personal development and leadership. This questioning should answer how far an employee (any employee but at the same time all employees) is involved and engaged. Only conscious employees, as Kofman cal s them, are able to real y contribute to the realization of the values. Afterwards, a conscious manager needs a space (a workspace) that gives the possibility, the support, and the drive for the conscious employee to contribute to the realization of values.

Kofman, when talking about the necessity for personal involvement and/or engagement, and personal development, uses seven qualities to distinguish conscious from unconscious employees. Together with each employee (or manager) the task is to try and see how far this person has come in becoming a conscious manager and if not, how this could be changed. The first three are character attributes: unconditional responsibility, essential integrity and ontological humility. The next three are interpersonal skil s: authentic communication, constructive negotiation and impeccable coordination. The seventh quality is an enabling condition for the previous six: emotional mastery.

In other words, the idea is that each employee/manager evaluates him or herself on those seven qualities.

• Unconditional responsibility

• Essential integrity

• Ontological humility

• Authentic communication

• Constructive negotiation

• Impeccable coordination

• Emotional mastery

Once comfortable with the fact that employees/managers are conscious (and therefore able to contribute to the realization of values), the next step is to consider the supportiveness of the environment for enabling that realization.

Buckingham and Coffman’s studies of organizational effectiveness produced an interesting checklist. According to them, exceptional managers create a workplace in which employees emphatical y answered ‘yes’ to the following questions:

25. Do I know what is expected of me at work?

26. Do I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work right?

27. At work, do I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day?

28. In the last seven days, have I received recognition or praise for doing good work?

29. Does my supervisor, or someone at work, seem to care about me as a person?

30. Is there someone at work who encourages my development?

31. At work, do my opinions seem to count?

32. Does the mission/purpose of my company make me feel my job is important?

33. Are my co-workers committed to doing high-quality work?

34. Do I have a best friend at work?

35. In the last six months, has someone at work talked to me about my progress?

36. This last year, have I had opportunities at work to learn and grow?

It is almost enough to count the number of yes responses to get an idea of the organizational effectiveness, or the degree to which employees and managers feel supported by the company in their endeavor to realize the corporate values.

Benchmarking: from dream to reality (do we make a difference?)

Imagine an organization that has been able to identify values or the anticipated valued added of its existence or activity. The next step in our continuing journey is to establish some kind of benchmark. Compared to other companies, activities or industries, does the organization deliver something that is not yet delivered elsewhere? Can a number of elements, which would give a certain concrete idea of the direction to follow, be identified? Would they real y be different, and capable of setting the industry standard? This kind of benchmarking is not done for competitive reasons or for finding blue ocean strategies (as in Kim and Mauborgne, 2005), but for helping to identify the difference that makes a real difference – in a very detailed and down-to-earth fashion. It is this analysis that will help enable our marketing support, our commercial argumentation, our commercial message, etc. It will help to translate values, mission and value added into communication (internal, as well as external).

In a two-step procedure, the first performs a rather classical benchmark analysis. The second attempts to evaluate the innovative potential. Is it possible to ensure that what is offered is a real innovation (rather than just a copy of an existing product or service)? Does the proposal have the potential to innovate the market, the industry, and to make a social difference? In aspiring to this new development what resources are needed?

For the first step, we base our analysis on an extended version of Kim and Mauborgne’s (2005) blue ocean concept. For the second step we use part of an innovation roadmap methodology (designed earlier within the innovative learning-by-doing platform and approach, for practicing managers to learn about management while creating and while managing, and captured under the framework known as the Innovation School). The roadmap itself contains more steps than the ones used here, but these are restricted to the most essential ones that fit the methodology proposed in this chapter.

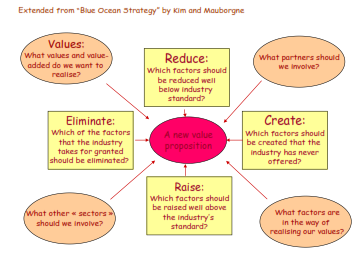

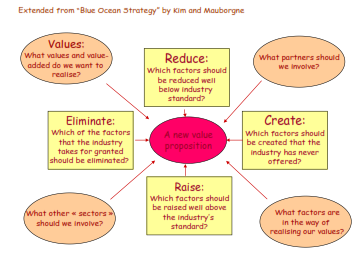

The first step is based on the following figure that is based on the blue ocean concept. The blue ocean strategy invites a company to develop products and services that tap into a blue ocean (an ocean without fierce competition, where it is pleasant to live, compared to a red ocean of “bloody” competition). The approach proposes to ask the following four questions:

5. Which factors that the industry takes for granted should be eliminated?

6. Which factors should be raised well above the industry’s standard?

7. Which factors should be reduced well below the industry’s standard?

8. Which factors should be created that the industry never previously offered?

The answers to these questions give an idea of how the company, new product, or whatever, positions itself in the market. Equal y, the answers, especial y to the fourth, give an initial indication on the innovative potential of the company, service, etc. Though these factors can be identified individual y, this is typical y an exercise done in an animated workshop, since some of the questions might be rather challenging.

However, we want to extend the blue ocean approach with another additional four questions that position the company (or its new product or service) within a broader network (of partners). We also want to relate to the specific purpose of realizing values, and demand a more intense and varied innovation focus:

• What values and valued added do we want to realize, compared to what exists (this time)?

• What factors are in the way of realizing those values?

• What partners (companies, organizations) should we involve?

• What other “sectors” should we involve in our activities?

It is worth recalling that one of the remarkable observations in social entrepreneurship is that companies and services are often not limited to one specific sector or industry. The social intrapreneurship advocated here aims to realize the same openness to others, and to enroll solutions into a holistic focus on the value added of the company (that will be reinforced by the use of Cassandra later on).

The second step in the process from dream to reality involves introspection on the innovative potential of the value added to be created, and on identifying a reasonable list of resource issues that would be related to the value added that is aspired to. The realization of this step is based on the “Innovation Roadmap”, a methodology designed and used for guiding innovation processes of any kind.

The original aim of the Innovation Roadmap was to support the manager in the development of a grounded business plan for a creative idea. In that process, the main focus is on the translation of the idea into a project that can be communicated to, and shared with others. Attention is also given to the screening of the innovative potential of the proposal, before translating it into the necessary resource inventory. Eventual y, that resource inventory, with proposed solutions for any possible snags, is translated into a business plan that investigates and reports on the economic and financial viability of the project.

Creation, innovation, and intrapreneurship are skil s, capacities and approaches that are typical for anyone seeking to remain competitive. During a project, the Innovation Roadmap supports the manager in order to facilitate the discovery of one’s own approach. The support that the roadmap gives should be seen as a structure and checklist; one will still need to walk the talk. One needs – as Machado says – to lay down the path in walking.

In the overall innovation literature, a clear distinction is made between the phase of creativity and the follow-up phase that is commonly addressed as the innovation phase (detailed planning and production). The first phase receives low priority (in the innovation literature), though most of that literature also agrees that success and failure of new product development is often already ‘genetical y imprinted’ at the start of the so-called innovation process, which is based on the quality of the creativity phase. A second commonly identified reason for failure can be found in the process of the creation phase. Where we certainly stress the importance of time and effort spent on the first creativity phase, we do require at least an inventory of the resources and limitations to overcome for the inventory phase, rather than the creation phase.

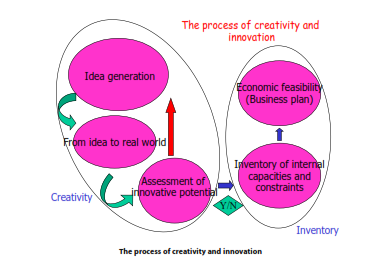

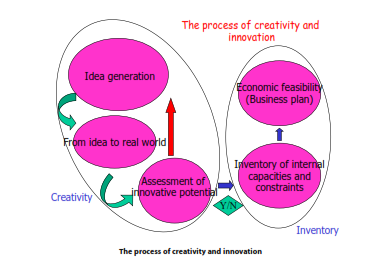

In short, based on what common theories suggest, an innovation process contains roughly five different phases:

1. Idea generation

2. From idea to real world (how to translate an idea into a concept that can be communicated)

3. Assessment of the innovative potential (and the commercial feasibility) of the project

4. Inventory of the internal capacities and constraints in order to assess technical feasibility

5. The economic (and mainly financial) feasibility – the business plan

Though a certain progression in time seems logical (certainly in the first three phases), some feedback loops will emerge as necessary and are extremely effective in adding value. However, at a certain point in time, and after a number of feedback loops, one should continue in the development phase and the economic viability study. The following diagram depicts the process, which will be detailed – with the help of some checklists and relevant issues/questions – further on in this appendix.

For the purpose of social intrapreneurship, we use only the third and fourth stage of the entire Innovation Roadmap. The figure above establishes the context of the approach. The innovation process starts with a phase of idea generation and/or creativity. This is the phase in which the wildest dreams can be transformed into ideas. Very often, this process gains momentum when undertaken in groups creatively (rather than by individuals).

A difficult step, very often, is then to translate the ideas into the real world. The idea can be clear in the mind of the idea-owner(s), but requires translation into a form that can be communicated to wider audiences. That is not a typical problem for the innovation process, but it is of paramount importance and key to further successful development. In order to support this vital step, techniques like soft systems methodology (SSM) are designed to transform ideas into the real world, with the aim of eventual y designing Information Systems.

Once the idea is translated from the owner’s mind into a form that can be communicated (with sentences, activities, to-do lists), its innovative potential has to be assessed. It is difficult to evaluate the innovative potential of an idea when it is not somehow embedded into a message and descriptions on paper. Therefore, this step can only be undertaken after the ‘translation’ from idea into activities.

The logical progression from idea generation, via translation into a communicative action and description in order to evaluate its innovative potential, is a cycle that does not necessarily immediately generate the eye-catching new product or service. Frequently, it is the insertion of a feedback loop that brings the process back to the phase of idea generation. Creativity and innovation very often proceed via a process of incremental steps, rather than individual earth-shattering breakthrough ideas. Indeed, this feedback loop often needs to be taken a number of times but the cycle of three phases remains the backbone of the creativity process.

In our social intrapreneurship approach, we take up the Innovation Roadmap methodology, presuming that a workable form of the project or the entire company is available.

Once a “go” decision is taken, the next phase involves researching the internal capacities and constraints that are key to a future successful implementation. In this phase an inventory is made of resources and constraints and, in case constraints would hinder the process, possible solutions need to be considered. Needless to say it is possible, though not indicated on the figure, to have additional feed-back loops bringing you back from the inventory phase into (again) the idea generation phase (and its subsequent steps). The more the innovation process can be kept dynamic, the higher the chances for innovative products. This fourth phase can also be integrated into the social intrapreneurship approach.

Final y, the economic and financial feasibility study converts ideas, capacities, and constraints into a business plan. The business plan very often acts as the communication tool for going to market in order to find support, finance, etc. for proposals, and should be considered as such. It is also a communication tool and should, therefore, be made attractive and clear. Though the business plan deals with the economics and financials of the project, most of those are already identified earlier on in the process. Therefore, we suggest that the business plan is more about financial feasibility and justification, than about economic viability which, implicitly, has already played a role much earlier in the process. Therefore, it is rather an outcome than an input. The important role of the business plan as communication tool, in the process from development to real market, needs to be kept in mind.

Assessment of the innovative potential

Many definitions of innovation exist and each has a different focus. In general, however, they tend either to concentrate on the creativity phase, the idea generation phase, or the process innovation side (that describes how to get from an idea to a realized product or service). A second criterion on which most of the definitions differ is the focus either on the breadth or on the depth with which innovation is associated. Certainly, in the first phases, breadth is important, and this is captured by West and Farr’s definition of innovation “as the intentional introduction and application within a role, group, or organization of ideas, processes, products or procedures, new to the relevant unit of adoption to significantly benefit the individual, the group, organization or wider society.”

Their definition of innovation also fits strongly with the concept of social intrapreneurship. In fact, in this definition, social intrapreneurship becomes a perfect example of an innovation. Accordingly, this part of the Innovation Roadmap can assess, at this stage, the innovative potential of the project. Possible outcomes could be to re-iterate the project (given the outcome of this phase) and select a new idea or, alternatively, to opt for the inventory of constraints and capabilities for successful realization inside the company and to continue the procedure.

Lessons learned from existing research are presented as useful checklists that can help in assessing the innovative potential of the project. This next section provides some general lessons (taken out of standard literature) and is followed by a section focused more on specific, experience-based learnings.

Some general lessons learned about innovation (that the user should turn into questions about his or her company or project)

• Character and culture are human creations, not facts of life. Context is therefore important

• All people have creative potential

• One cannot separate creativity and the possibility of generating new products (sometimes called the capability to transform ideas into viable solutions)

• Creativity is different from creation (production, re-production, etc.)

• Creativity often needs motivation

• Creativity has to do with freedom of choice and choice itself

• For creativity, multiplicity is important because multiple realities always exist

• Recognition of demand is a more frequent factor in successful innovation than recognition of technical potential. Already in this phase (and not for the first time in the business plan) demand requires some attention

• Training and experience of people inside your company are crucial for innovation

• Were any lessons learned from other (external or internal) innovations?

• Don’t innovate for the future, but for the present

• Effective innovation starts small and is often not revolutionary

• Innovation and learning go hand-in-hand; innovation and management are a different ballgame

The recommendation is to make a list of those lessons that the company does explicitly take into account (and comment on them, describe their context, etc.), and those that might need more attention. Not all of them are always equal y applicable.

Questions that should always be addressed concern the innovative potential of the project:

• Why (goals)?

• What (product-novelty)?

• When (timing)?

• Where (targeting)?

• How (marketing mix)?

Certain identified potential fail factors are worth considering during this stage, when they can still easily be avoided:

• Go for the “better” product (without clients)

• A me-too product (is often too slow)

• Obstruction (unexpected) of the competition

• Products for low-margin markets

• Badly prepared introduction

• Fast introductions

• The newer, the better

• Position a new product as the successor of another one

• Change the positioning of the product (too fast)

• Pricing too low

• Organizational limitations and barriers such as culture, limited managerial support, lack of competencies. Though those aspects get much more attention in the next phase, some initial exploration should take place here.

Moreover, those observations should be turned into questions that merit responses, comments and contextualizing.

Potential success factors worth considering at this stage (are they present in the company, project or product?) include:

• Intrinsic value of the product

• Structured and well-managed development and introduction process, insofar as there is already a clear idea about this (perhaps a wish list could be made)

• Understanding the needs of users

• Attention to marketing and publicity

• Efficiency of development

• Effective use of outside technology and external scientific communication

• Seniority and authority of responsible managers – commitment

• Team composition

• Individual creativity

The strongest positive correlations with success are:

• Product advantage (costs, innovativeness, quality, satisfying needs)

• Proficiency of pre-development activities (initial brainstorm, screening, thorough market analysis, technical assessment, financial/business analysis)

• Good protocol of all specifications

Ticking all those questions/issues should ensure a reasonable potential to add value to the market.

Inventory of capacities and constraints

Once the concept is ready to be evaluated against the capacities and constraints of the company, the creativity phase gives way to the inventory phase. In this phase the project is assessed against the expected strengths and weaknesses that your company has in respect of innovation. In some cases, the corporate environment, for many different reasons, is somewhat hostile to new, truly innovative projects. This can be due to a range of factors from the organizational structure, through the lack of commitment from top management, to the culture of the company itself.

Support in this phase can again be provided by a few checklists. The first ones are more general in nature and are based on what is commonly known as the NPD (New Product Development) literature. They mostly relate to the establishment of the additional innovation process. By recognizing possible pitfal s early on, firms can possibly avoid them. The latter checklists, and some of their learnings, are based on research into some real-life projects.

Some challenges for the future NPD process of your project:

• Not everything can be realized. Therefore, making trade-offs between different “important” aspects of a new idea is essential. Attempt to identify these aspects and prioritize them.

• Dynamics: how to deal with changing technologies, preferences, opinions, ecology, economy. Is your project vulnerable to rapid changes?

• Details: small decisions can have large consequences (possibly even on a larger scale)

• Time and timing. How crucial are these?

Some possible fail factors:

• Team that is not empowered enough

• Political (hidden) agendas, on various levels

• Inadequate sourcing

• Incomplete design team

In essence, the NPD process, which will eventual y follow your project, is an uncertainty reduction process. NPD also involves seeking and keeping sponsorship. Often, innovation needs sufficient cash, and the following additional success factors are critical:

• Commitment from the top to the project

• Planning and design

• Involvement of employees in the project

• Education and training

• Internal communication

If these are not addressed, then this is the stage to spend some time on them.

The introduction of social intrapreneurship is, at the end of the day, a large change management project, as well as a new ‘concept’ development project, hence the deployment of lessons learned in the new product development experience. For certain cases and companies, this phase might be less adequate. The book leaves it to the judgment of the reader, or the consultant using this methodology, to decide whether this might be a value adding part of the process.

Some experience-based lessons learned:

The checklist presented here is based on the learnings of a number of real-life innovation projects that have been studied. Since the cases were ‘assembled’ at the end of the innovation project, some of the issues are clearly related to the process itself. Not all of them are applicable to any particular project. For improving a social intrapreneurship change process, certain lessons will add more value:

• Reasons for delays often mentioned are: changes in the project team, insufficient resources (availability of people), no clear specifications, insufficient interface between teams, universal optimism and opportunistic planning, outside influences

• Insufficient project management skil s

• Insufficient communication on decisions

• Frustration of team members

• Unclear responsibilities

• Not all expertise required is available

• Reinvention of the wheel

• Insufficient management commitment that contributes to stress, pressure, and insufficient resources

• Contracting problems if third parties are involved

• No proper risk analysis available

• Changes in the concept that occur during the project realization are often not checked for risks and consequences

• Market tests are often executed far too late

Having detailed all of this, and deciding to go for it, the next areas of focus are the leadership’s checklist and the management diagnostics.

The leadership’s checklist: do I make a difference?

As argued earlier, the role of the leader, and what it might involve, is v