Chapter 13—Work the toughest issue: how much to bid?

The simple-minded, obvious approach to bidding is to read your customer’s request for proposal, come up with a project design, estimate what the package will cost, add profit and perhaps a contingency, and submit that amount as your bid, without giving the matter another thought. That might work often enough in road construction or provisioning where the technology is well settled, and the work content is well defined and understood, but in any high tech or otherwise unusual project, it often is recipe for failure, especially if the market is shrinking or competition is intense.

Our goal in this book is to move well beyond this obvious bidding approach. We will try to gain some appreciation of the dynamics of the bidding situation, and also some appreciation of what bid amount is appropriate to ensure you getting your share of the work. Even when other factors are involved, bid amount is vitally important. Much more often than not, the low bid wins. Such is the state of the world. People like bargains. So your goal always will be to bid as low as you can and still make a reasonable profit when you win. Another even more important goal will be to win often enough to be able to remain a viable, competitive organization.

The winning formula we advocate in this book is simple. We have spilled a lot of ink developing the nuances of it, and will spill even more in later chapters, but here is the basic process:

-

Get an early start and maintain momentum (Chapter 1).

-

Be clear about who the customer is and who “we” are (Chapters 2-3).

-

Find out what the customer truly wants (Chapters 4-7).

-

Find out the “competitive range” of bid amounts (Chapter 8).

-

Give the customer confidence that we are capable and reliable (Chapter 9).

-

Find a baseline project design that minimally meets the customer’s needs and that the customer can afford (Chapters 10-11).

-

Look at the competitive situation—how many effective competitors are out there, which ones are “hungry,” what they are able to offer in terms of project design (Chapter 12).

-

Work the issue of how much to bid (this chapter, with support from the next chapter).

-

Get your proposal right and keeping the game going (Chapters 15-18).

Our main concern in this chapter is with a concept we call the “competitive bid.” Shortly we will provide a definition for it, and discuss underlying principles of a model for estimating it. Following those principles, you might want to build for yourself a computer model to help you work through a best bid analysis in a systematic and repeatable manner. Or, you might wish to contact the authors to obtain such a model, already built in MS Excel®.

A competitive bid, as that term is used in this book, is not a bid that guarantees a win, or even that promises a high probability of a win. There is no such thing, unless you are in a probably illegal collusion with your customer. A competitive bid is based on a process designed to get you your share of the work, provided you are competent in the realm in which you are bidding. This book will not make you competent in any field if you are not, but we do provide many suggestions that will help you be more competent (see Appendix A).

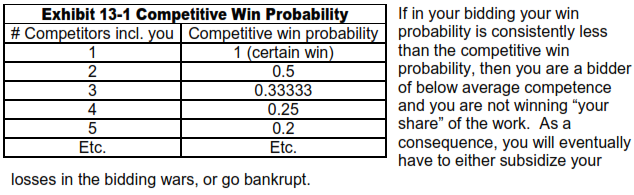

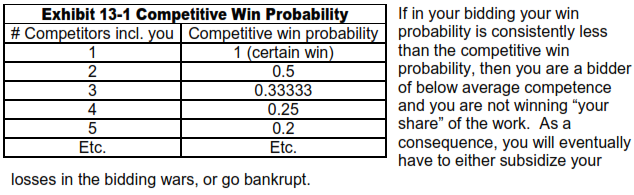

We begin with a question that is not merely rhetorical. It has a widely accepted mathematical answer: If there are N+1 bidders including you, and all bidders are equal (an important qualifier!), what is the win probability of each? Based on a pretty much universally accepted principle called the Principle of Insufficient Reason, it would be 1/(N+1). This principle originated with the famed mathematicians Jacob Bernoulli (1654-1705) and Pierre Simon Laplace (1749-1827). Basically, the principle says that if there is insufficient reason to believe otherwise, and if N+1 outcomes of an event are possible, each outcome has probability 1/(N+1). It is due to this principle that we say that the probability of heads on a “fair” coin toss is ½, and the probability of a five on the toss of a “fair” single die is 1/6. Recall that a coin has two faces and a die has six sides.

Accordingly, we can create the following table:

So, a logical starting point in determining your bid amount would be to determine your competitive win probability, all things being equal. That begins with determining the value of N, the number of competitive bidders that will enter the competition, other than you. You can safely exclude bidders who have little or no chance of winning. Such exclusions, of course, are a judgment call, the first of several you will have to make to decide on your bid amount. (Sorry, there are few certainties in this process. Some subjective judgments are inevitable.)

Of course, you and your competitors can’t bid any amount you want and expect to win. In the real world, there is something called the “competitive range.” If any competitor bids outside this range, it is reasonable to assume that the customer will throw out that bid. Therefore we posit that all bidders contained in your assigned value of N are aware of the competitive range and know that they must bid within it to have any chance at all of winning.

If the potentially successful bidders are all aware of the competitive range, it follows that the customer must also be aware of it. But, it is reasonable to ask, will all of the potentially successful bidders and the customer all have in mind exactly the same range? The answer is probably not, unless the customer publishes it, which has probably never happened and probably never will. For one thing, the customer may not, on any given day, know exactly where the bottom and the top of the range are. However, it is fair to say that an astute customer and an astute bidder will know the bottom and top values to a reasonable approximation.11

There is always some uncertainty associated with determining the boundaries of the competitive range, but nevertheless, a best attempt at nailing down these values is a very worthwhile exercise for every competitor. The reason why should become clear shortly.

The parameter N+1 exerts a pressure on all astute competitors to either bid lower, come up with a technology offering more pleasing to the customer, or both, if they hope to win. But that is not the only factor that has such an effect. It is convenient to give that other factor the name “competitive pressure.” You have more competitive pressure when, for example, at least one serious bidder is “hungry,” as when that bidder’s management says “this is a must win for us—pull out all of the stops.” You also may have more competitive pressure when one serious bidder has a known “edge,” that is, some perceived advantage which might cause the customer to look with favor on that competitor’s bid even if it is a bit higher than some of the others. The edge could be a number of things, such as excellence of design, a track record of good project results, or even a political consideration, like being located in Alabama (it happens!).

In addition to N+1 and competitive pressure, another factor which tends to drive bid amount is cost risk. This is the ever present possibility that your cost estimate missed something in a fixed price or risk sharing bid, or that you might overrun your estimate in a cost plus bid and alienate your customer. Depending on circumstances, the effect of such alienation might range from essentially no effect to contract cancellation and / or a strong bias against you in future bids. Clearly, the lower you bid, the more your cost risk.

Given what has been said so far in this chapter, we submit that the following should be done in every bidding situation, as a minimum:

-

Determine N and calculate 1/(N+1).

-

Strive to arrive at a some combination of bid amount and product offering that results in a win probability of at least 1/(N+1).

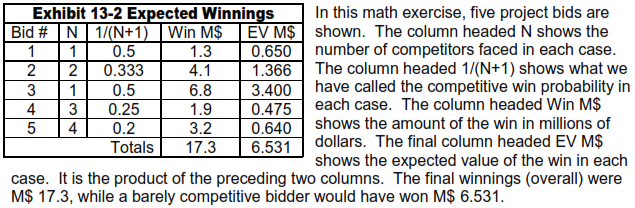

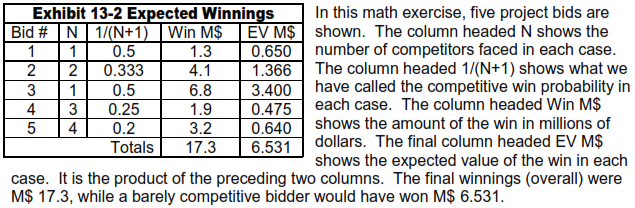

If you have concerns about the usefulness of doing this, you might want to conduct a brief analysis of your own bidding history similar to the following example.

If you do this analysis for yourself and your actual winnings were less than the sum of the EV M$ column, you have work to do! What kind of work? You could have one (or more) of several kinds of problems. Let’s look at a few possibilities.

-

Risk aversion. You could be so concerned about the possibility of losing money that you are afraid to lower your bid below what you believe to be a comfortable value. This may stem from a previous bad project experience. Suggestion: Review your risk management process. Look ahead to chapter 14.

-

Waste. You may have a lot of wasteful processes. See Appendix A. If you have been considering beginning a Six Sigma initiative, this would be a good problem to start your “belts” on.

-

Inexperience. Are you trying to punch above your weight in the technologies you are bidding? If you are, you will probably keep getting clobbered. Consider either staying longer in the minor leagues, or hiring the kind of people you need to compete with the big boys.

-

Poor cost analysis. Does your cost team understand the kinds of work you are bidding? Are they competent? See Appendix D.

Assuming that you are free from any of the above problems, it may be that you are just not keeping your pencil sharp enough when you are trying to determine your bid. Let’s keep firmly in mind that the goal is to create a bid that gives you at least a 1/(N+1) win probability. Is this easy? Not usually. It can be very hard. The larger the value of N, the harder it gets. In fact, for any value of N greater than 5, it’s all but impossible. In fact, for N > 5, a bidding situation is more like a lottery than a competition. The outcome is likely to be, or appear to be, essentially random.

For competitions where N  5 there is some hope of profiting from a comparative analysis, meaning an analysis in which you compare your own state of readiness to the readiness of you competitors. By your readiness we mean, to what extent have you created a worthy project management structure and process; to what extent do you understand what your customer needs; to what extent can you satisfy your customer that you are meeting those needs; to what extent is your customer happy with you; to what extent is your design solution balanced and efficient, etc. In other words, to what extent are you doing the things recommended in chapters 1 through 11 of this book?

5 there is some hope of profiting from a comparative analysis, meaning an analysis in which you compare your own state of readiness to the readiness of you competitors. By your readiness we mean, to what extent have you created a worthy project management structure and process; to what extent do you understand what your customer needs; to what extent can you satisfy your customer that you are meeting those needs; to what extent is your customer happy with you; to what extent is your design solution balanced and efficient, etc. In other words, to what extent are you doing the things recommended in chapters 1 through 11 of this book?

The Best Bid model, mentioned earlier in this book, contains a questionnaire that asks you about such matters. It asks you the very same questions about each competitor. Other questions pertain to the issue of competitive pressure. One possible answer to the questions about competitors is “Don’t know.” If you give that answer, the model assumes that the competitor is just as ready as you are. For competitors that are more ready, and for high competitive pressure, the model assumes that bids will be clustered more tightly at the lower end of the competitive range. This makes it harder for you to win.

The Best Bid model puts a high premium on knowing your competitors and the state of the market. The better your state of knowledge in these subjects, the lower will be its recommended bid amount, and the more likely it will be that you will win, assuming that you can see your way clear to bid that low!

Creative and mathematically adept types among our readers might well profit from building a model along the lines discussed, and using it to predict a best bid. Others might want to acquire the Best Bid model your author has already created. Contact the author if you want to do that.

A caution: The Best Bid model we have built, and any similar model built by a reader will by definition be an economic model. As most economists will (or should) admit, economic models have a long history of being wrong. Therefore you should not wholly trust the Best Bid model, or your substitute for it, until you have ignored its recommended bid amounts at least five times, and made your own bid amount assignments instead. After you have done that, you can check the results. An excellent way to check the model results is the simple expected value calculation demonstrated earlier in this chapter. If using the model results would have resulted in too many losses, the Best Model has a calibration adjustment to correct that. If you decide to build a model, yours should have such a calibration adjustment feature, too.

Your author has worked with proposal managers who would never put their trust in any model for determining bid amount. Mostly, these are people who have great confidence in their ability to “read” a complex situation and come up with a winning solution. To such people, we offer our congratulations. But we do make one recommendation. After each bid amount decision, take the time to write a memo to the file explaining exactly how you came up with the bid amount. After the award has been made, take that memo out and read it. How accurate were your predictions?

Chapter 13 Review Questions

1. Explain in your own words the concept of a competitive bid, as that concept is developed in this book.

2. If you are to stay in the contracting business, without subsidy, why must your bids be at least competitive, on average?

3. On your last major pursuit, did you know who all of your effective competitors were?

How did you find out?

4. For several consecutive days, a researcher gave 20 mice in a cage only an ounce of cheese. The mice frantically scrambled for the cheese and most of the mice went hungry. After observing their behavior, the researcher began to give them all the cheese they wanted. The mice ate in a casual, leisurely way and no mouse went hungry. Is this situation a good analogy with the notion of varying levels of competitive pressure in the Best Bid model?

5. Is the Rule of Insufficient Reason reasonable? Explain your answer. (There has been some controversy about this rule.)

6. Customers of a Cadillac dealer are probably more willing than customers of a Chevrolet dealer to pay for unnecessary frills and “loving care.” Are your customers more like Cadillac customers or Chevrolet customers? If they are more like Cadillac customers, we recommend you give this book to a friend who needs it and instead read “Customers for Life” by Carl Sewell, et al. But even if your customers are more like Chevrolet customers, Sewell’s book is still an excellent source for ideas on pleasing customers.

5 there is some hope of profiting from a comparative analysis, meaning an analysis in which you compare your own state of readiness to the readiness of you competitors. By your readiness we mean, to what extent have you created a worthy project management structure and process; to what extent do you understand what your customer needs; to what extent can you satisfy your customer that you are meeting those needs; to what extent is your customer happy with you; to what extent is your design solution balanced and efficient,

5 there is some hope of profiting from a comparative analysis, meaning an analysis in which you compare your own state of readiness to the readiness of you competitors. By your readiness we mean, to what extent have you created a worthy project management structure and process; to what extent do you understand what your customer needs; to what extent can you satisfy your customer that you are meeting those needs; to what extent is your customer happy with you; to what extent is your design solution balanced and efficient,