VI For the Future

Chapter 17—Keeping the game going

Review of the nature of advanced contracting

The kind of contracting this book is about is the kind of contracting in which the bidder is judged on his total proposal package. Bid price is a very important part of the package, but hardly all of it. Many factors may be considered to determine the winner in a given case. To distinguish it from the kinds of contracting where low bid is the only consideration (other than being qualified to bid), we call it advanced contracting. That label seems justified, because to remain competitive bidders must be “up to speed” in their technical discipline, and must stay that way.

Some organizations engaged in advanced contracting are also engaged in a multitude of other activities. Generally, however, there exists one or more identifiable components of such an organization whose primary raison d’etre is the advanced contracting function. This discussion will be indifferent to any organizational matrix within which the advanced contracting function may happen to be embedded, since the focus will be on certain planning and decision problems unique to the advanced contracting business.

A characteristic of the advanced contracting business which distinguishes it from the more traditional forms of competitive contracting such as most simple construction, drayage, provisioning, concessions, etc., is the multiplicity of criteria which the contract sponsor may apply in determining the winning bidder. In traditional contracting, award of a contract to other than the low bidder generally requires specific justification, and in many instances is so exceptional as to be newsworthy.

In advanced contracting each bidder is judged on his total “bid package,” and on the basis of other special criteria as well. The bid package typically consists not only of the traditional letter or form disclosing the bid amount, but a host of other disclosures, such as:

-

Demonstration of understanding of the technical nature of the project being bid.

-

Demonstration of competence in the technologies involved in the project.

-

Outline of a proposed technical approach.

-

Identification and qualifications of key personnel who will be involved.

-

Proposed schedule of performance.

-

Location of the contractor’s facilities.

-

Location of principal subcontractor facilities.

-

Level of unemployment in contractor’s locale.

-

Contractor’s present workload and work capacity.

-

Recent similar contract awards.

-

Contractor’s technical and managerial reputation.

-

Size and resources of contractor’s organization.

Another distinguishing characteristic of advanced contracting might be called “high technological flux.” In traditional contracting, new technology tends to be absorbed only after it has proved convincingly superior to the “old way.” In advanced contracting, on the other hand, new technology may develop on an almost daily basis; the advanced contractor must at least stay abreast of the state of the art of all of the technologies germane to the contracts he wants to bid.

To be aggressively competitive, he sometimes must even advance the state of the art. Technological flux influences his ability to win contracts, and it affects his ability to perform contracts he may have been awarded. This is especially true of contracts where a new state of the art must be created in the course of performance. Such contracts may be said to carry a high technical risk.

A third distinguishing characteristic of advanced contracting is the diversity of contract funding arrangements. In the traditional situation, the qualified contractor submitting the low bid wins the contract, and he is expected to perform using the amount of the bid as his sole reimbursement. There may be exception clauses in his contract which afford some protection in the event of strikes, natural disasters, inflation, etc., and there may be bonuses for early completion and/or penalties for late completion. All of these arrangements are used in advanced contracting, too, as well as some others which the conventional contractor seldom encounters, such as cost-plus-fixed-fee funding, or cost-plus-fixed-fee with incentives. When a request for proposal specifies one of the cost-plus-fixed-fee types of funding, the amount of the bid may well be lower than when a fixed price arrangement is specified, since the risk to the contractor is generally less.

Usually, cost-plus-fixed-fee funding and its variants are used by sponsors in recognition of the fact that the contract subject matter involves high technical risk. Because of this risk, the level of performance achievable for a given amount of money is always in doubt, right up to the time the money is actually spent. Similarly, the amount of money needed to reach a given level of performance is in doubt, right up to the time the performance actually is achieved.

Thus, the cost-plus arrangement allows the contractor to pass on some (perhaps most) of his risk to the contract sponsor, who generally has deeper pockets than the contractor.

In summary, three major characteristics have been identified which distinguish advanced contracting from more traditional forms:

-

Multiplicity of criteria which the sponsor uses to select the winning bidder.

-

High technological flux.

-

Diversity of funding arrangements.

In the next section, we will address a set of important planning and decision problems that are unique to organizations that survive by winning bids in the arena of advanced contracting.

The advanced contracting annual planning cycle

Advanced contracting organizations, like most other serious firms, usually have an annual planning cycle, that is, at about the same time each year certain aspects of their situation are reviewed, and certain decisions are made as to probable future actions. In general, the decisions will include such matters as approaches to take in obtaining new business, budgets for business search and proposal activities, including budgets for internal research and development. Also considered will be management of continuing work on existing projects (“backlog”), and profit goals.

The advanced contractor’s annual planning exercise is often an update of a three-, five-, or seven-year master plan. Because of the uncertainties in the advanced contracting business, however, plans which go beyond the forthcoming year tend to contain a lot of wishful thinking, except for backlogged business which may sometimes extend several years into the future. Even backlogged business occasionally has a way of drying up and disappearing for one reason or another, which introduces further uncertainties.

While the annual planning sessions set the tone for the coming year’s activities, it is a rare advanced contracting organization which completes a year with its annual plan intact. There are many reasons for this. For one thing, in many firms the contract turnover is high, i.e., the gross revenues in a given year may contain only a relatively small amount of business which was backlogged at the beginning of the year.

Another reason is the high degree of technological flux already mentioned. Sometimes technological breakthroughs or difficulties affect contracts in such as way that planned cash flows are suddenly changed, up or down.

Yet another reason is that annual plans tend to make definite assumptions about the outcomes of pending competitions for new business, about the number and kind of new business opportunities that will arise as the year progresses, and about the outcomes of those competitions. While the assumptions may seem very reasonable at the time they are made, things usually turn out to be different, which means that the annual plan must be adjusted one or more times during the year.

With all of the uncertainties, it is very common for advanced contracting firms to engage in a substantial amount of re-planning and revised strategizing as the year progresses. Indeed, in a great many firms, the re-planning required consumes much more time and effort than the original annual plan. Going even further, one can say that in many firms with high contract turnover (usually the smaller firms) one of the principal functions of first level line supervisors is to re-plan their manpower needs in terms of available funds, sometimes as often as weekly. Similarly, middle managers are concerned with re-planning because it is needed to determine realistic departmental and divisional work force levels and work priorities. Top management also is concerned because, in the high state of flux characteristic of advanced contracting, potential profits can evaporate quickly if planning does not keep up with developments.

The advanced contracts business is highly labor intensive, and a large fraction of the labor force tends to consist of highly paid technical professionals. Thus, cash flows for labor costs are usually by far the largest component of the negative cash flow for any contract. Further, adjustments to the labor force (except by natural attrition) are difficult to make in most instances. Hiring new professionals to fill out a deficient labor force is time consuming and expensive, and the new people are usually of limited effectiveness for at least a month or two, while they are learning their new jobs. Unfortunately, a labor force deficiency today may turn out to be a surplus tomorrow, considering the uncertainties. Laying off professionals to reduce a surplus labor force is agonizing to top management because of the human values involved, and also because, after a certain point, it tends to weaken a firm’s technical capabilities and overall employee morale.

Because of the nature of the labor force in the advanced contracts business, a primary goal of most re-planning is to achieve stabilization of the labor force insofar as possible. Indeed, many advanced contracts firms treat this stabilization as a goal secondary only to the overall profitability of the firm. In some cases, immediate profit gains are sacrificed for the sake of stability, on grounds that stability will enhance longer term profits. Planned schedules are sometimes modified for the same reason.

With the preceding discussion providing the necessary background, it is now possible to describe a typical advanced contract firm’s planning cycle. We let it begin at some convenient “time zero” as a point of reference. Beginning at that time, management undertakes to establish its instantaneous situation as a baseline for the planning. This baseline typically comprises the following seven elements:

-

Human resources. The array of technical and managerial talent embodied in the skills of personnel comprising the firm’s current work force.

-

Physical resources. The inventory of equipment and facilities usable by the technical and management personnel in the performance of their work, including items such as scientific equipment, computers and computer codes, factory machines and tooling, test facilities, office buildings, vehicles, etc.

-

Financial resources. Cash reserves, securities, receivables, lines of credit, etc., which are available for use in the course of business.

-

Inflexible financial commitments. Debts, bond redemptions, contracted services, leases, pensions, etc., and other factors which act to limit the range of business operations.

-

Flexible financial commitments. Payroll, payroll related expenses, rentals, travel, services, consultants, etc., the level of which can be adjusted by management to meet changing conditions.

-

Backlogged business. Business already under contract and the implications of that business for use of human and physical resources, and the likely effect of that business over time on financial resources, inflexible financial commitments, and flexible financial commitments.

-

New business prospects. New business for which there is a non-zero win probability of capture in the coming year and the implications of that business for use of human and physical resources, and the potential effect of that business over time on financial resources, inflexible financial commitments, and flexible financial commitments.

The backlogged business represents obligations that must be met over the coming year and perhaps longer. Normally, these contracts will make possible net positive cash flows which will be the basis of at least a part of yearly profits. Also, they will require use of at least part of available resources. Sometimes there is uncertainty about the continuation of all or part of backlogged business due to sponsors’ possible desires to expand or reduce the scope of the work.

If the firm has a large backlog of highly certain business, with low contract turnover, it may elect to give relatively little consideration to new business prospects. As a rule, however, advanced contracting firms are highly concerned with seeking out new business, and with structuring their planning to take it into account.

From this point, it will be helpful to proceed using a numerical example. To that end, let us imagine a small firm called TEK-R-US that is currently doing its annual plan. We will focus first on the positive cash flow effects of backlogged business and the prospects for new business, returning later to other effects that may result.

Suppose that TEK-R-US has three contracts backlogged. Following is the relevant information:

-

ABC Project. A certain source of $250,000 per month for the first six months, $100,000 per month for the next four months, and $50,000 per month for a final two months of the current year.

-

DEF Project. A certain source of $50,000 a month for the first eight months. After that time it is hoped, but not certain, that the sponsor will exercise an option resulting in an additional $25,000 per month for four more months of the current year. A probability of 50% has been assigned to exercise of the option.

-

GHI Project. This project is experiencing severe technical difficulties. It may be cancelled. If cancelled, it will yield $100,000 per month for the first two months and nothing thereafter. If not cancelled, it will yield $100,000 for four additional months. A probability of 50% has been assigned to cancellation.

We assume that TEK-R-US also has identified three projects that it has better than a zero probability of winning. Suppose that the following describes these potential projects:

-

JKL Project. If won, this project is expected to produce no revenue for the first three months. After that, it is expected to produce revenues of $100,000 per month for the rest of the year. A win probability of 55% has been assigned to this project using the Best Bid model.

-

MNO Project. If won, this project is expected to produce no revenue for the first five months. After that, it is expected to produce revenues of $50,000 per month for the rest of the year. A win probability of 38% has been assigned to this project using the Best Bid model.

-

PQR Project. If won, this project is expected to produce no revenue for the first seven months. After that, it is expected to produce revenues of $150,000 per month. A win probability of 22% has been assigned to this project using the Best Bid Model.

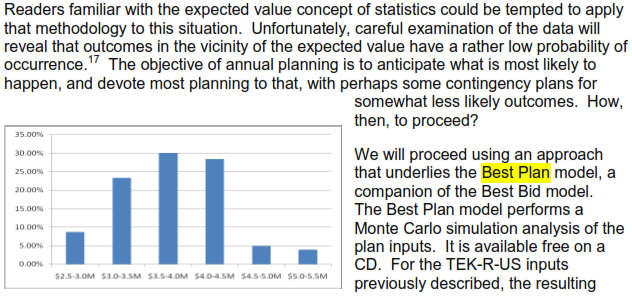

histogram is shown nearby. The most likely outcome is revenue between $3.5 and $4.0 million. That has a probability of 30%. There is an almost equal probability of an additional half million in revenue. The probability of about a half million less is 23%.

TEK-R-US would apparently be wise to focus its planning on revenues of about $3.5 million, with contingency plans for as low as $3 million and as high as $4 million.

In addition to a histogram such as that shown here, Best Plan also discloses the most likely combinations of wins. In this case, the most likely combination is to fail to get the project DEF option, project GHI does not get cancelled, and all three competitions for new work are lost. This combination has revenues of $3.1 million. Almost equally likely, however, is the outcome where the DEF option is picked up by the customer and TEK-R-US wins the project JKL competition. This combination has revenues of $3.7 million.

Strongly suggested by the results is that TEK-R-US should try to find more projects to bid, else the year following the current planning cycle could be a very bad year.

The Best Plan Model provides additional information as well:

-

Revenues and costs by month due to project operations.

-

Staffing profiles by month by skill code for each active and anticipated project.

-

Material costs by month for each active and anticipated project.

-

Profit and loss due to project operations by month and cumulatively.

The Best Plan model is a management tool to assist bidding and project management. It is not intended to be an accounting model for the firm. Its concern is with the effects of project operations.