3.6 Behavioral characteristics and financial service usage

Behavioral and personality traits can affect people’s financial behavior. For some aspects of it, such as propensity to complain to financial consumer protection authorities, they may be even more significant than sociodemographic characteristics (Mazer, McKee, and Fiorillo 2014). Among the objectives of this research was to explore to what extent behavioral and personality characteristics correlate with the level of financial service usage.

During the quantitative survey, respondents filled in a personality test questionnaire on their attitude toward money per Furnham’s Money Beliefs and Behavior Scale (Furnham 1984). According to this methodology, people’s beliefs about money are measured against the following six dimensions:

1. Obsession refers to being obsessed/anxious about all aspects of money.

2. Power/Spending refers to treating money as a means of power.

3. Retention refers to being careful with money.

4. Security/Conservative refers to traditional approaches to money.

5. Inadequacy refers to feeling of having not enough money.

6. Effort/Ability refers to the means by which one obtains money.

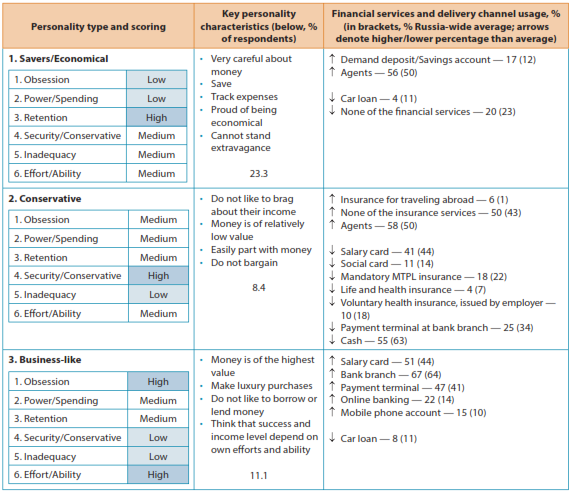

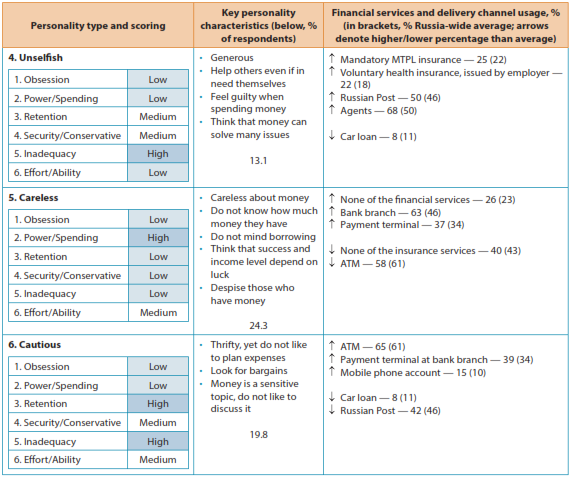

For the purposes of this research, an adapted version of the Furnham questionnaire was used.42 Based on statistical analysis, the research identified six main personality types based on their prevailing attitudes to money, which conditionally were called ( i) savers/economical, ( ii) conservative, ( iii) business-like, ( iv) unselfish, ( v) careless, and ( vi) cautious. Table 6 presents the types with the scoring per the dimensions of the Furnham Money Beliefs and Behavior Scale, along with the findings on the correlations between them and the level of financial service usage.

The research revealed that the correlations between the identified personality types and financial service usage were certainly evident, though not as strong as between sociodemographic characteristics and financial service usage as discussed in Chapter 2. In terms of specific products, the “savers” segment (as the name would suggest) shows higher usage of savings products, and lower usage of car loans. The “business-like” segment shows higher usage of salary cards (which may correlate with higher employment levels in this category), as well as much higher usage of all types of delivery channels, including the innovative ones, as compared to average figures. Among the “careless” segment, the share of nonusers of any financial services is slightly higher than average. Overall, somewhat higher correlations were found between the personality types and the usage of the delivery channels rather than the usage of specific products.

This information may be useful to providers as they design and market their services and delivery channels (e.g., marketing a product as prestigious for the “business-like” segment, or as a “good deal” product for the “cautious” segment). This also may be helpful for policy makers and other stakeholders working on financial literacy programs and standards for financial services descriptions (e.g., appealing to the need for security by the “savers” segment, or a need for doing something good with the help of money by the “unselfish” segment).

As this is the first such attempt at tracing financial service usage to personality characteristics, more research is necessary in this area that would test various other methodologies evaluating personality types — in terms of their applicability and usefulness for predicting or explaining the usage of financial services.

Table 6. Correlations between personality types and financial service usage

Detailed breakdowns of the survey results are presented in Annex 3.