Expansion and Contraction

There’s a phrase we hear all the time: “Don’t reinvent the wheel.” The way it applies here is that I believe there are some very original ideas in this book and this system, but there are also some things that are simple truisms that you already know— things like “buy low and sell high.” I’m sorry, but I can’t take credit for that one; it’s been said somewhere else before. Real estate investment has been around a long time, and sometimes it seems like there isn’t much new that can be said about it. Yet, often it is not just that perhaps there is a new idea, but rather a new way to conceptualize what is going on around you and how you can better analyze and take advantage of it.

From watching markets ebb and flow, like the tides, I was able to create the following original way of looking at markets.

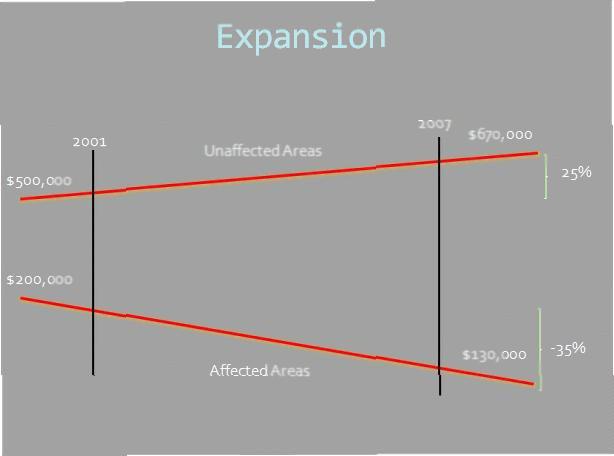

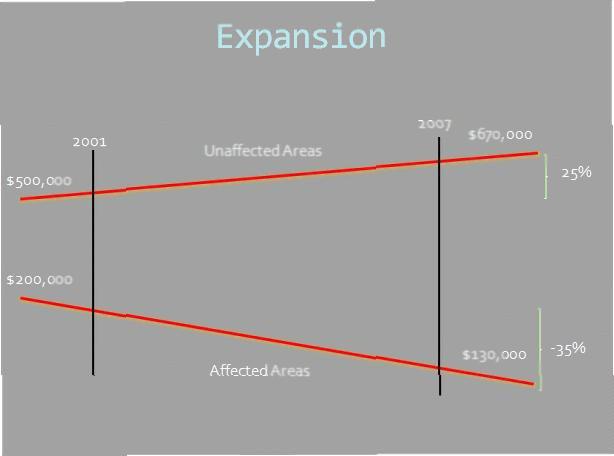

Expansion

Expansion within the market occurs during the later part of the down cycle. Expansion represents the large disparity between the prices of entry level housing and high end homes. This occurs because during a recession in a geographic area the people most likely to be affected are the lower priced or entry level buyers. When jobs are lost, usually the lower paid workers are affected more due to higher qualified employees entering the market. This makes it difficult for people who are renting to become home owners due to unstable employment and lower wages. Affluent, more stable wage earners earn on, mostly unaffected by the recession. The higher end or high demand properties will continue to be stable or grow. Over time, the disparity between the two prices greatens, creating the expansion.

During what I term “expansion,” foreclosed properties and pressured sales are thousands of dollars below the retail market. Example: Right now, there are homes in my area that I can buy for $140,000 where there is an almost identical home on the same block selling for $190,000. But this system is not about simple, quick turnaround. Yes, I could buy and resell that within six months and make $10,000 to

$20,000. But I would probably have to put almost that much into them in order to make them retail-able.

After Arizona boomed, I did my research and found some interesting possibilities

in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2004, I called a real estate agent there her comment was “What are you talking about? Our market’s flat; it’s only going up about five percent a year; it’s not a good market.”

I answered, “I think you’re sitting on the best market in the Country!”

I bought there on expansion. I bought the cheapest, lowest priced, distressed property that I could find. Not necessarily in bad areas, but in high foreclosure areas. During 2005, these general areas went up fifteen percent, but I made a fifty-five percent total return. Why? Because it had all that room to swing back up. And remember, these receded markets first have to catch up to the regular market before they can move forward. But you can make these huge gains on them.

In Sacramento in 1997, there were condos for sale for $6,000. A few miles away, I had relatives living in $475,000 homes. The whole thing confused me at the time. How could this be? Now I get it. It’s expansion. But nobody ever taught this concept before. Yet it looked so perplexing from the outset that it scared me out of the market.

Expansion is the Opposite of Stimulants.

Expansion typically happens in “bedroom communities.” In a recession, people tend to move inwards toward the jobs. Thus, the areas NOT affected by positive ripples are the most receded, with the highest foreclosure rates. This is where you want to buy early. Once you hit around ten percent appreciation and you can no longer find cash-flow properties and you’re buying strictly on appreciation, then you want to flip-flop to identifying the stimulant markets and getting into those. Here is what I mean by an “expansion” market:

As you can see, there is a definite disparity between luxury homes and “affordable housing” (call it “starter homes” or “rental properties”—all of these terms work). Despite what one might consider a recession, the higher end properties continue to rise or at least hold value, but the lower end is dropping like a stone, losing significant value. If a large employer moved out of a geographic area, this is the sort of

market we might be looking at. Lower wage earners would be out of work. They would have to sell in order to leave the area and go to where the jobs now were. Higher wage earners might be, say, commuters, people living in luxury developments who could afford to work in a far-away metropolis while living far from that

metropolis, out where they could hear the birdies chirp in the morning. These people are not affected by the loss of some local factory and so their homes continue to rise in value.

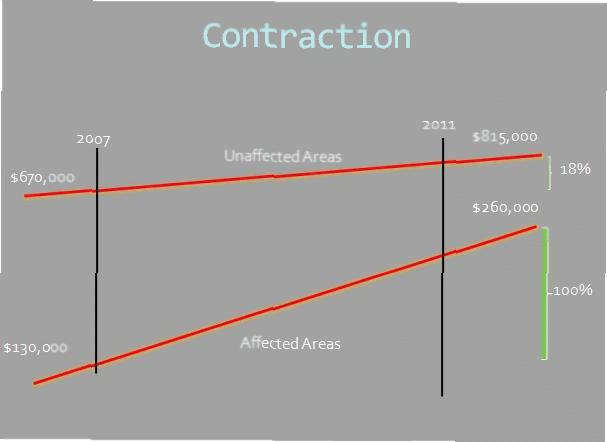

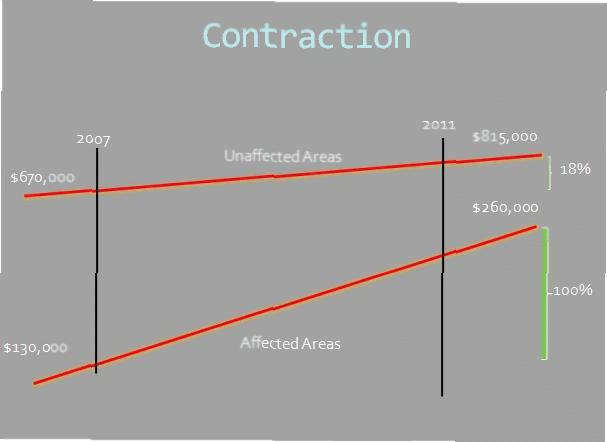

Contraction

Contraction is just the opposite of expansion. When a market is in the fourth quarter of a growth cycle, the high demand for housing places pressure on the lower and mid range priced homes. The pressures are caused by the incredible increase in values in such a short period of time. When people hear of the rapid growth in a geographical area, they buy urgently and aggressively like sharks in a feeding frenzy. During this feeding carnage, the lower end properties begin to close the gap between them and the higher end or more desirable areas. In some cases it is difficult to discern between the property types.

Here is what contraction looks like:

Now, you might wonder why the high end properties have not appreciated as greatly as the lower end. This is because there is not an infinite ceiling to housing prices in a geographical area during a given period of time.

Looking at the two illustrations, we see that in real dollars, the average lower end home did not actually increase in value all that greatly. In 2001, it was $200,000. In 2011, it may go up to $260,000, an increase of only $60,000. But it is what happened in between that is what is most interesting to us. $200,000 dropped to

$130,000, then doubled in value to $260,000. What we would have wanted to do is buy not at $200,000, but when the property was $130,000. That’s something only a person well-versed in market cycles knows how to do—somebody like YOU.

Understanding expansion and contraction allows us to create greater margins in the same markets that others are struggling in. We will identify the weaker areas in the Down Markets. Weaker areas may be areas of the highest foreclosure rates or not the most desirable locations. In growth markets these same properties will trade within a few percentages of their perfect counterparts.

Tides

Here is another way to visualize housing markets. Picture an ocean’s tides. You are probably already familiar with the quote made most famous by President Kennedy when he said, “A rising tide lifts all boats.” That one has been

used in many a business guide, as well as by all sorts of economists.

But let’s take the “tides” analogy in a different direction. We can call high tide “the good times.” The water is deep about fifty feet from the shore and even the driest part of the beach, up near the highway, is getting wet.

That normally dry area that is finally feeling the moisture of the waves is new housing construction. A geographic area is doing so well, so fine in fact, that new housing needs to be built. Dry sand is finally getting wet (I keep slipping between metaphor and reality).

During these good times, if we tried to buy land fifty feet from the shore, we would drown—as waders, we would find it too deep, and as investors we would find it too expensive. In either case, we would indeed go under and not come back up. On the other hand, we know this much about the tides: they change. They cycle. Gradually, it becomes low tide. The water that once reached far, far into the mainland recedes, leaving everyone high and dry. It is safe now to walk around thirty, forty or fifty feet from the shore. Now it is safe there.

Here is what is most important to understand as we compare tides to housing markets: When a market gets hot, more housing gets built. The physical size of the market grows. An area that was four contiguous square miles expands to become five contiguous square miles. New developments sprout up. What was once open space becomes suburban housing.

Further analysis… The new housing being built where housing had not existed before becomes the most desirable housing. Why? Because it’s newer. It has been designed to meet the needs of today’s market. Housing built twenty-five years ago was built based upon what the public wanted way back then. Things change. Consumer tastes change.

This is very good for developers; they create a very desirable product and can sell it at a premium price. Even if what they have built is not necessarily intended to be luxury housing, it still can sell for more than older housing simply because people like “new.” Talk to someone in advertising. “New” is one of the all-time best words in advertising. Tide laundry detergent has been called “New Tide” for decades. Is it really new? No! It’s just that we, as consumers, get excited by that word. We don’t want other people’s hand-me-downs; we want new!

This new construction on the outskirts of town will be over-priced. We, as investors, don’t want it.

So what

do we want during this high tide period?

Nothing. This is the time for us to be getting out of a market, not into it. We cannot “buy low” at this time; so instead, we “sell high.”

Now, let’s study those tides again. It’s low tide now. What happens to housing during low tide? Well, it differs a little from real low tide on a beach. There, the land farthest from the water dries up and blows away. In real estate, the opposite happens. Remember—new is still new. Even when it starts to get a little old, if it is the newest thing around, that still makes it…well, it makes it the newest thing around. The newest thing will remain the most desirable, particularly when it is developed in a new area that has greater privacy, perhaps larger yards, more acreage, quieter, better paved streets— whatever the amenities are that the public most demands today.

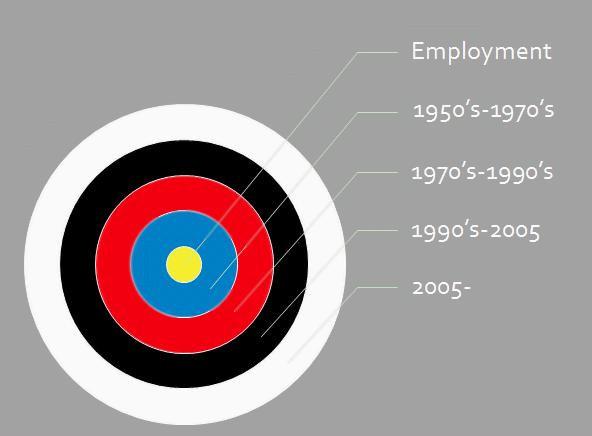

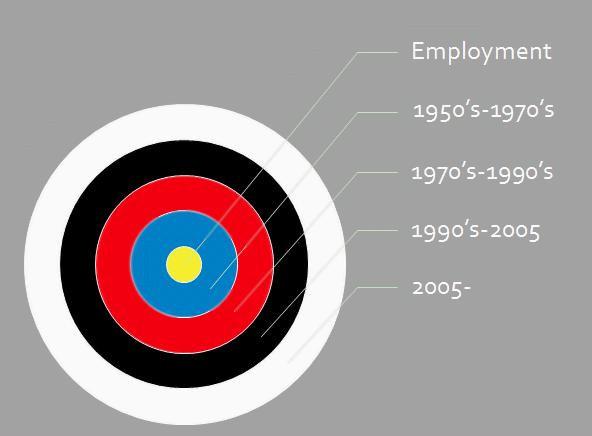

Bull’s Eye!

Let’s switch now from tides to targets. When we were at high tide, the black outer ring of housing was built—all that nice, new stuff. The yellow in the center? That’s industry. That’s where the jobs probably are. Even though that black outer ring is farthest from the employment, it will most likely be inhabited by the most affluent people, people who can afford something nice and new and want the quiet and solitude of being a bit farther from industry. These people can afford to commute a little farther.

Consider this: If you could afford to live anywhere, would you want to raise your children in the shadow of a big, dirty factory? Of course not. Yes, for there to be a target at all, there must be that yellow center of industry (think about what we said earlier about “stimulants”). But historically, that metropolitan area probably started with only the yellow industrial center and the red ring just outside of it. As each high tide of good economy arrived on the scene, another ring of newer residential construction was built, each further out, farther from the industrial center.

Here’s what I want you to learn: When that tide first became high and the second residential area was built—the blue ring—those properties sold for more than the red ring, but the need for the blue ring’s existence caused the red ring’s properties to also appreciate in value. “A rising tide lifts all boats!”

But when low tide had its turn in the market cycle, the blue circle was newer than the red circle and so it retained its value more—it was still the place to be if you were still living in this general area. And what happened to the red area? That’s where the foreclosures happened. That’s where the property abandonment occurred. That’s where housing stayed and stayed on the market, unable to be sold.

THAT is when we want to buy houses in the red circle, and the red circle is where we want to be buying. For when that tide begins to rise again, that red circle is where the renters will find places like yours to live.

When the next high tide occurs, the white ring of even newer housing will be created. Home values in the red and blue rings will rise with the white. Things will be good—if you already own investment housing in the red ring. You will have lots of tenants knocking at your door and they will be willing to pay high rents. You will make money, although at some point I might encourage you to sell, because this is when you will get your highest price from those guys who always think things will just keep going up, up, and up and never come down. But hey, we know better than that. We understand tides. They come in and then they go back out again. They don’t just keep getting higher and higher forever.

Low tide cycles around again. The white ring is the newest and so it retains its value. What will get hurt the most? The red ring, for it is now the oldest. Where should we be investing now? Now would be the time to buy in the blue ring. We could not afford to invest there before—we would not have been cash-flowing as landlords. But now the red ring properties are becoming pretty darn old and distressed. The blue ring has also seen better days, but again, it is more the kind of place where we want to be. We do not want to buy in extraordinarily bad, seedy, crime-infested neighborhoods. We cannot cash-flow in the best, but we also don’t want to be in the worst.

This is the way of the cycle—like an ocean’s tide; like a dart board target. Visualize it and understand it and you will be able to make money at it.

Buying During Expansion—Retail versus Wholesale

Okay, so now we know to buy during Expansion rather than Contraction. Expansion means that the supply of housing has “expanded” and so we can buy things at a lower price. Supply and demand. The more there is of something on the market, the cheaper it will be priced—it’s called competition. The opposite is Contraction, where there are more people than there are places for them to buy; the amount of available housing has “contracted.” In those markets, there are bidding wars to buy even the most modest homes, overpricing them. This is great if you are selling, but it is anathema if you are buying.

So let’s say you’re in an expansionary market, which you’ve identified because I’ve taught you how. You’ve identified the neighborhood where you should be buying. So let’s cover one last thing, something I’ve alluded to a few times: We want to buy “wholesale” instead of “retail.”

Now what does this mean? In other areas of life, it means, for example, that the shoe store owner buys his shoes from a manufacturer for $20, which is called the “wholesale” price, and then he sells them at his store for $80, which is the “retail” price. So how on earth could we be using those same terms when it comes to real estate, unless we are a developer who “holds back” a few units for himself?

Even during a market expansion, some properties will be priced better than some others. This is not merely comparing luxury homes to lower-end homes. It means that, even when comparing apples to apples, some properties will be “distressed” while others will not.

What distresses a property? Well, of course, there is the image conjured up by the word “distressed” itself. Run down. Ugly. Falling apart.

This is fine, as far as we are concerned, but only up to a point. There is an entire science to understanding how much money can be invested into a property in order to make it financially viable. Here is also where we differ from the Fix and Flippers. A lot of them will buy a property so that they can fix it up really nicely as a kind of “repairman’s hobby.” That’s great if it gives you genuine pleasure. As far as making a profit, though, there is definitely a point of diminishing returns. What you have to bear in mind as a person buying property to hold for a while is that you need only make it habitable for rental tenants. A Jacuzzi in the master bath might be desirable to a buyer, but it’s a bit over-the-top as an amenity to a renter.

We, as people who will be buying property to rent, need only look at a physically distressed property and decide, “How much money will it take in order to simply make this place habitable?” Once that data is arrived at, we can then calculate that additional amount into the purchase price and then run our numbers again in order to decide if things will cash-flow well for us. If it is still what we might consider “wholesale” at that time, then we might want to buy it. But sometimes adding in that extra cash to bring it up to code only serves to make it “retail,” which means it is no longer any different from any other house on the market.

One of the ways in which a property is truly at a “wholesale” price versus a “retail” price is if it is in foreclosure or is a bank-owned property. Here is a real-life example that I was involved with:

What we are looking at here are two properties, nearly identical properties, in the same neighborhood for sale at the exact same time. Study the pictures closely. There are no discernable differences. The one on the left is owner-occupied and is for sale with a regular real estate agent. The property on the right is a foreclosure.

Now, what might shock you is not only that the foreclosed property sold for

about $40,000 less (and that’s REAL money, people), but look how much longer it was on the market. The higher priced property took less than a month to sell, but the one for $40,000 less took over four months to sell. How the heck can that be?!

Perception is everything . Properties that have been foreclosed are perceived by the public as having less value. Prior to going into foreclosure, the property owner will not have been able to have invested much, if any, money into the property. A piece of rain gutter may be falling down. The kitchen garbage disposal might not work. A window may be broken. When you are struggling to pay the mortgage so that the bank doesn’t take your home away, these little repairs are not your priority. You’re taking every dime you have and giving it to your mortgage lien holder, not Home Depot or some handyman. So the “retail” property is most likely to be in “move in” condition, while the “wholesale” property may need a few bucks tossing into it in order to be habitable.

Have you ever heard of what Realtors and “retail” buyers go through in order to make their property have “curb appeal?” When they are showing it, they mow the lawn, they hang a few new pictures, they clean the place up until it’s immaculate, they put potpourri around to give the place a beautiful scent. No effort is missed.

The “wholesale” property owned by the bank via foreclosure? You may be taking your life in your hands when you walk inside. Dead rodents may be under the sink, stinking up the place. I mean, this is no “little step down,” people; this is the difference between pride of ownership and “Animal House.”

So what does this do to the price? The “retail” property is doing all this so that you can envision your lovely family growing up and growing old there—a real homestead. The “wholesale” property is “as is,” and if you don’t like it, tough on you.

Even in an expansionary market, people are more apt to rush in to buy the “retail” property. It is geared toward owner/occupants, and there are more of those than there are residential real estate investors. The “wholesale” property? Not only will it be pretty gross and dirty, in need of some minor repairs, perhaps, but your only competition to buy it might be “Lowball Larry.”

Now Lowball Larry, he’s a funny guy. Larry thinks that no matter how low the price is, if he waits long enough, it will go even lower. Lowball is the wise guy who, no matter what anyone ever pays for anything, will always counter with, “I could have gotten it cheaper.” The problem is, Lowball rarely ever makes a deal because he waits too darn long. The property in our pictured example was on the market one hundred thirtysix days. Lowball Larry figures if he waits a year or two, then the price will be really low—maybe around $75,000. And he’s right; if it’s around that long, it probably will be far lower.

But we don’t want to be like Larry and never get the deal. We see the property on the left and its price; we see the property on the right and its price. We see how long the property on the left was on the market before it sold. Now if we see the property on the right, see how much lower its price is, and see how much longer it’s been on the market, we should know that IT’S TIME TO JUMP IN AND BUY!!!! The old gambler’s adage is, “don’t get greedy,” and that’s exactly what Lowball Larry’s problem is. What I’ve shown you is a perfect example of retail versus wholesale.

Since we are assuming that this is an expansionary market, our numbers should actually work well with either property, but our numbers will really work well with the wholesale property, the cheaper one, the bank-owned one, the one that smells funny. Buy that one and buy it NOW.

WANT to Sell versus HAVE to Sell

I don’t want to focus exclusively on a wholesale property being in distressed condition. I know that probably conjures up all kinds of negative images, not just purely esthetic, but also as it broaches the topic of investing money into the property in order to simply make it habitable.

Perhaps a better way of describing things is to say that “Wholesale” pricing is when a seller HAS to sell, while “Retail” pricing is when a seller WANTS to sell. There are some situations where the wholesale property is not necessarily physically distressed, but there are other mitigating factors. For example, prior to foreclosure and a bank assuming ownership of it, one way in which a person can avoid foreclosure is to quickly sell the house before foreclosure action has occurred. This is a smart move for a person with mortgage payment problems because it enables them to save their credit; there are very few things worse than a foreclosure on your credit report. At that point, they are really just trying to get rid of the house for what is owed on it. If, by chance, the party in question put up a standard twenty percent down payment and, perhaps, paid off a bit of the principal before hitting hard times, you might be able to buy it for, say, twenty percent less than what it was worth when he bought it.

For example:

Original purchase price: $200,000

Mortgage: $160,000

Principal paid $5,000

Amount seller needs: $155,000

This formula can get even better when we factor in that the home price may have appreciated over time:

Current value: $250,000

Amount seller needs: $155,000

In this scenario, you might be able to purchase the property for $95,000 less than its retail value. That’s a perfect definition of “buying wholesale.”

There are some other situations where a property falls into the NEED to sell versus WANT to sell category. Sometimes a large and prosperous employer guarantees to relocate their employees and find them housing. This perk may include purchasing their old home from them and then reselling it. When this happens, the employer really isn’t set up for being a landlord, so they’ll simply try to dump the house as quickly as possible. What is the quickest way to dump a house you don’t want to own? Sell it at “wholesale”! If the company is doing well, losing $30,000 or $40,000 on a deal like this isn’t the end of the world—it’s like a bonus paid to a good employee and their accountants will find some creative way to write it off.

Bottom line: Be on the lookout for “wholesale” housing prices in the neighborhood where you want to buy. Be wary of a deal that’s too good to be true, but be willing to be a little more flexible than if you were going to live in it yourself. Buying wholesale versus retail can be the difference between winning and losing in the real estate investment game.