CHAPTER 4: WHERE I CAME IN

Nothing takes as long as growing up. An hour is a hundred

minutes, a day is a week, a week a month. And each month, waiting for the

seasons to change, seems like two. A small house is huge, the front lawn a

football field, a damned-up stream an Olympic swimming pool.

Lightning bugs provide eternal fascination. Kick-the-can and

hide-and-seek lasts all evening long. Fun goes on forever, but on our few bad

days, the suffering does, too. And as the clock turns, we want to grow up

faster. The process is far too slow. But the inevitable happens. An hour turns

into thirty minutes. The days and weeks grow shorter. The months and years

flash by. Things get smaller, nature gets overlooked, our calendars get

crowded. Fun comes only in glimpses, no longer a day-long affair. The things we

plan or anticipate too quickly come and go. Time rushes by, and we realize

those long, long days we had growing up were simply not real. When we are old,

the short, short days we know pale in comparison when we remember, in

retrospect, that nothing goes by quicker than growing up.

—Roy H. Park, Jr. (2004)

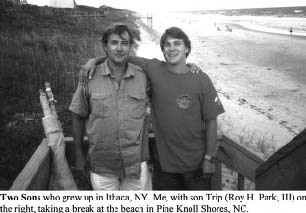

While all this was going on, this transplanted southern-born

kid was growing up a Yankee in Ithaca, NY. Although I remember aspects of my

early years, they mostly come back as strobe-lighted flashbacks, like passages

in a book highlighted by a magic marker.

At the age of four, I was hyperactive enough to drive my

mother crazy. Maybe all kids are. I know it applies to my grandchildren.

Looking back at the old movies my father took back then, I spent most of my

time running around and making noise. Of course those old projectors did tend

to make movement jerkier and faster than it actually was.

Shortly after we arrived in Ithaca, I am convinced, more to

get rid of me than anything else, my mother enrolled me in an experimental

Pre-K school at Cornell University. Back then the school was essentially

carrying out experiments in educational methods, and we were the guinea pigs. I

learned that they observed us through one-way glass, and they performed a lot

of experiments to study the interaction among us four- and five-year olds.

While the other kids were scrambling around on the jungle

gyms and swinging on swings, I developed a healthy, or some might call it

unhealthy, interest in animal life. It included col

lecting every bug I could find on the playground. I guess

that was regarded as an indication of a high IQ because they gave me a really

fine score at the school. (Perhaps it is merely a coincidence, but Cornell is

known to this day as the home of renowned entomologists, not to mention a certain

amateur lepidopterist and author of Lolita named Vladimir Nabokov.)

My interest in living things sustained itself through the

years. I raised orphaned robins, raccoons, opossums, and cottontail rabbits as

well as baby chicks, turtles, alligators, and iguanas. I even built a homing

pigeon coop in our backyard when I was twelve years old.

All this experience eventually led to extremely high marks

in biology and science courses, but not so high marks in languages, history,

and, particularly, math. This lack of interest in figures was to make my later

education much more difficult.

When we finally moved out of our crowded apartment and into

our first home, it was in a district that put me in the fairly elite Cayuga

Heights School. I was enrolled along with a large number of Cornell professors’

sons and daughters. It is interesting to note that our house on White Park Road

was three houses down the street from the revered physicist and Nobel Laureate,

Hans Bethe, and I walked by his house each day to catch the school bus when I

entered high school. The best memories I have are that we all kept our noses

clean and got a good basic education. Many of us stuck together right through

high school, and even college.

I remember my first girlfriend. I was about eight years old,

when, as with young women, her growth spurt came early and she was taller than

me. I had a bike. She didn’t. She would follow me as I was riding along, and I

felt guilty about her running along beside the bike on the way to school. But I

got over it since being on the bike made me taller than she was.

Believe it or not, when we got a little older, most of my

elementary school counterparts even attended dance classes. One of my mother’s

favorite memories is of a young lady a good foot taller than I was at the time

who took a liking to me. She would always grab me as her partner. Since she

developed early, and tended to hold me tightly behind my head while we were

dancing, I came close to smothering on these occasions. My mother still reminds

me of my attempts to come up for air on the gym dance floor.

I have fun kidding my grandsons about their possible

girlfriends today, and until recently even the oldest before he reached

fifteen, maintained he wasn’t that interested in girls. When I was growing up,

our crowd had plenty of interest in girls, and I had my first date at age

eleven, and she was back at our fiftieth high school reunion in 2006.

My father drove us to a movie theater, and after we got a

little ways into the picture, I put my arm around the back of her seat.

She snuggled over toward me to the extent the seat would

allow.

I thought things were going pretty well. About fifteen

minutes later, my arm began to feel numb, but I left it behind her anyway. I

thought she would think I didn’t like her if I moved it. When we finally left

the theater, I had no feeling on my right side. Pops picked us up, and it took

hours for my arm to regain circulation and be usable again.

Another not-so-favorite memory was of my mother’s taking me

shopping in downtown Ithaca. These shopping trips were always embarrassing

because my mother, with her genteel Southern upbringing, never went anywhere

without a hat. She had two she favored. Both made her stand out in our small

town like a lighthouse during an eclipse. One had a bunch of red cherries off

the side, the other a cluster of pheasant feathers that stood straight up. The

good news was that I could always spot the hats above the counters and aisles

of whatever store we were in. So I never got lost.

GROWING UP IN ITHACA As John Mellencamp reminisced in his

1987 song “Cherry Bomb,” when you think about those days, you just have to lean

back and smile.

During these early years, while most kids were earning a few

bucks with paper routes, tossing papers from baskets on their bikes, I was

putting all my eggs in one basket with something unique: an egg route. At my

father’s instigation, I was talked into it by a local farmer, and I had to be

careful riding my bike with such fragile cargo. I could deliver the cartons to only

one or two customers at a time before reloading.

It went well for a while, but a problem arose when the

customers (I had signed them on with advance payments of 12¢ a carton) ran out

of eggs. And so did the farmer. In fact, he abruptly left town, so there was no

way I could fill the advance orders.

For a while I thought I would have to come up with the money

myself. Fortunately, my customers were forgiving and I avoided filing

bankruptcy at an early age.

After the eggs crossed the road with the chicken, I held an

array of summer jobs through my teens and later during college.

There was never a summer that I didn’t work. I mowed lawns,

weeded, and killed Japanese beetles eating the neighborhood’s hollyhocks for a

penny each by dropping them into a jar of kerosene. For a couple of years, I

even tended an experimental iris farm. The owner was a Cornell professor, whose

nephew, Anthony Perkins, later starred in Psycho. He was said to visit his

uncle each summer, but I never saw him.

During my preteen years in Cayuga Heights, I also fell in

with a group of neighborhood kids who mostly went to Cayuga Heights School, and

who ran in age from seven to thirteen. We played games in every yard in the

neighborhood, from hide-andseek to kick-the-can to football. One yard was large

enough to field a baseball diamond.

With my next-door neighbor, we put on our version of a

carnival for a couple of years. It included a merry-go-round with pump handles

(substituting for the wooden horses and other animals on the real thing), caged

birds and animals, magic acts, horseshoe pitching, and other reasonably safe

try-your-skill sideshows.

Our animal acts included white fantail pigeons, which lived

in a coop but flew freely around the property. We safely colored them every

shade of the rainbow with Easter-egg dye. We attracted quite a few kids. Most

important was the admission charge, but in true carny spirit, we also charged

separately for each exhibit, such as the baby rattlers, which were actually a

couple of baby rattles in a toy crib, and it was too late to get your money

back after discovering the hoax. Not only were the admissions nonrefundable,

but we nicknamed one of the youngest marks “sugar bowl” because after he ran

out of pennies for the exhibits, he would run home to get the coins his mother

kept in a sugar bowl, assuring us that he would be right back.

As we grew older, the carnival attractions were replaced by

riskier activities. In those days in New York you could buy cherry bombs that

would disintegrate a mailbox like it was cardboard.

We discovered another application for this firepower. If you

lit a cherry bomb and put a coffee can over it, you could make the coffee can

blast out of sight.

Predictably, the neighbors complained about the noise, and

on one of our more active days, a patrol car came by just after I had put a

cherry bomb under a can. The only thing I could think to do was to hold the can

down with my foot, since we were in plain sight and couldn’t run.

When the firecracker went off, the can lifted my leg about

two feet in the air and numbed it for the rest of the day. It’s a good thing I

didn’t stand with both feet on the can, not being able to fly. The police, of

course, confiscated our firecrackers and threatened us with jail if we messed

with fireworks again.

And, yeah, as I said, we played the real kick the can, and I

still get goosebumps when I hear “Olley Olley in Free,” or however it goes in a

song or mentioned as in Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone episode Kick the Can. We

also did all the other usual things kids did back in the 1940s, too, playing in

our own and invading our neighbor’s lawns until we were exhausted, refreshed

only by warm water from garden hoses.

We played until the light gave out, climbed trees to the

top, tunneled under the forsythia bushes, caught crawfish in the streams, kept

garden snakes in the window wells, shot at each other with BB rifles, camped

around fires in the woods, and built forts for protection during our snowball

fights. We made piles of leaves in the fall, and when we got tired of jumping

into them, we set them on fire without worrying about fire trucks coming by.

In the winter, we sledded down the middle of the road on the

hill where we lived. In the summer, we used red Radio Flyer wagons, which had

no brakes. We rode our bikes on sidewalks, in traffic, and through front lawns

and woods without helmets.

As summed up in Mellencamp’s words in “Cherry Bomb,” “I’m

surprised that we’re still livin’.” But I also spent a lot of time alone, in

safer pursuits, en

tertaining myself by reading, sculpting, drawing, painting,

and collecting and keeping fish and animals. From these early days and

throughout most of my life, I have been a naturalist, keeping and studying

everything from praying mantises to alligators and iguanas, tree frogs to

raccoons, even opossums. I’ve kept saltwater fish tanks for years, with corals,

invertebrates, and fish including many versions of Finding Nemo clownfish. To

this day I have dozens of descendents of the dinosaurs called birds flying

around in a conservatory.

And along with birds’ nemesis, cats, I have owned dogs from

tiny Chihuahuas to Alaskan malamutes, mutts, and Russian wolfhounds, and from

Rottweilers to Belgian, German and Australian shepherds.

My mother told me I even had a goat when I still lived in

Raleigh, and it pulled me around in a little cart. I have seen pictures but

don’t remember it. My father did not share my indiscriminate passion for animal

life. Depending on his mood, he ignored or was only vaguely aware of my

menagerie. Occasionally he petted some of our dogs on their heads—and sometimes

petted me on my head, too.

I also have fond memories during those early years in Ithaca

of the many summers I spent with my maternal grandparents at Livingson

Apartments in Allentown, PA, where Dent Hardware, the family business of my

grandfather, Walter Reed Dent, was located. I watched many baseball games on TV

with him, and made many visits to the Trexler animal preserve with my

grandmother. I remember her allowing me to walk downtown to a pet shop,

accompanied by my new friend, the janitor’s son, whenever I visited, and bring

back anything I wanted. One time when I brought back a white mouse, and my

friend, who was black, brought back a black mouse, we laughed and kidded each

other all the way home to the apartment over our respective choices.

My grandfather was a lot of fun to be with. We got along so

well because to me he was young at heart and he knew how to talk to kids. He

had a great sense of humor and a great exit line. When he got tired of playing

with us, he’d ask if we’d like to see him walk like a duck. We’d say “Yes,” and

he’d exit the room and not come back.

When I later went away to Lawrenceville, he kept up a steady

stream of correspondence. His letters were funny and clever. Occasionally he

would call me on the phone. When we got together, he loved to play games. He

watched games on television for hours, until glaucoma, which was difficult to

treat at the time, took his sight. When he couldn’t watch TV anymore, he gave

in to old age and made his own exit proudly into the light, not walking like a

duck.

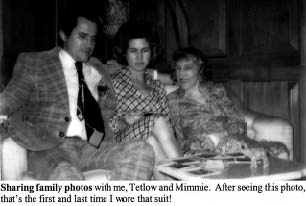

After my grandfather passed away in Allentown, my

grandmother came to live with us in Ithaca. I called my grandmother “Mimmie,”

since I couldn’t pronounce “Mildred.” She called me “Buddy,” since she knew how

much I disliked the “Junior” part of my name. When things were tough, her

advice to me was that this, too, would pass. She told me that pain, whether

physical or mental, does not last a fraction as long as the good things that

happen to you, and when the pain is gone, you can’t remember it. The few good

things are the things that last, she said, and her beliefs would serve me well

in dealing with my father in the future.

Roy H. Park, Jr.______________________ 71

As I mentioned, my great-grandmother, Love Caswell Houghton

(who I called “Muddie,” probably in another of my attempts to communicate at an

early age, in this case to say “grandmudder”) moved in with us when the family

first came to Ithaca. She also came with us when we moved to our first house on

White Park Road. When she began to fail she expressed a desire to return to her

native Raleigh for her final years. My mother took her south on the train and

found her a room in the Sir Walter Raleigh Hotel next to a longtime family

friend, Margaret Hall, a resident of the hotel for years. Our friend, whom I

knew as “Maggie,” looked after her until my great-grandmother passed away in

her beloved Raleigh.

My grandmother, “Mimmie,” God rest her soul, died peacefully

in my parents’ house in Ithaca, in her sleep, at age 109. After a century of

giving, this frail little lady had clung to life with tenacity. She was always

cheerful and a good listener, and she made everyone feel like the most

important person in the world. Her love of animals and her devotion to my

mother and her grandchildren were evident to all who knew her. She loved poetry

and literature and wrote hundreds of poems throughout her life. This had an

enduring influence on me. An avid student of the Bible, she knew the truth of

Ecclesiastes that death is the destiny of every person, and that the living

should take it to heart. One of the poems she wrote was read at her memorial

service on February 21, 2001: O God, in peace and tender love Grant thou a

soul’s request A body worn—a heart grown tired Yearns for thine holy rest.

Fleet winged would I now embark Into that joy-strewn past

Traversing e’en the dark unknown To reach thy blessed heart.

And find my savior dwelling there Within the far off gate

With only His sweet gracious love Apart from bitter hate.

So Father from whom comes all good Guide through our

faltering light Call Thou a vagrant spirit home This pilgrim of the night A

body tired, a weary heart Longs for the perfect rest Against thy shelt’ring

heart of love Within thy holy breast.

—Mildred Goodwin Dent I remember every Christmas that my

grandparents would come to Ithaca. It was one of the few times that Pops would

put aside his work in the evenings, or on a Sunday, for a game of Monopoly with

my grandfather and me. It was my father’s favorite game, but I was warned by my

grandfather to keep an eye on the board. If both of us became distracted at the

same time, Pops tended to make a few moves on the board that weren’t the result

of throwing the dice. He didn’t look at it as cheating; he just wanted to win.

And winning, in life as in Monopoly, was what mattered most to him.

CHRISTMAS SHOPPING Another Christmas memory includes the

last-minute shopping that Pops did for my mother. A day or two before

Christmas, he would take me with him to the best women’s store in town,

Holley’s, where he would invariably buy fancy negligees for my mother, ones

which would embarrass even Victoria’s Secret. My mother would immediately

return them a few days after Christmas. Their taste in sleepwear ran in

different directions, but the routine was always the same.

Sometimes when Pops ran out of time to shop for her, he

would give her cash and ask me the morning of Christmas Eve to come up with a

creative way to package it. I would quickly construct a cardboard house or

something with nooks and crannies into which he could tuck money. On one

occasion I was asked to find the unoriginal series of boxes that fit into each

other. The payoff, of course, would be concealed in the smallest and last box

she would open, but each box would have to be wrapped, and that was also

delegated to me.

To be fair, my father was young and obsessively busy then,

and as time went by he would plan ahead and pick out more substantial gifts for

her, such as jewelry or cars.

The worst part was Christmas Eve, after he had purchased

gifts for all his business associates, employees, and friends, including the

maitre d’ of the Dutch Kitchen in the old Ithaca Hotel, and we got in his car

around 4:30 pM to deliver them. My job was to run up through slush and snow to

each house or business he frequented and hand out the gifts while he waited in

the warm car. This took place no matter how bad the weather, but it was one of

the few occasions I could spend time with him. I figured it was one of the ways

I earned my keep. But this circuit-riding gift-giving had another unfortunate

aspect—it delayed the start of Christmas dinner each year, which in turn

delayed the opening of family presents on Christmas Eve.

We opened gifts on Christmas Eve in our house. The arrival

of Santa Claus, and our truly important presents were reserved for Christmas

morning. Christmas was real family time—and there was precious little of that.

FAMILY TIME When I was about ten years old, we were on a

rare family outing, a two-week cruise through the Bahamas. My mother and Pops

wanted me dressed for the part. They bought me a brilliant red jacket, which I

thought made me look like an organ grinder’s monkey. Plenty of girls my age

were on board. That jacket stood out like a beacon, but their reaction to it

was the opposite of attraction. After enough snickers from them, I discovered

that the small public bathrooms had portholes just large enough to accommodate

a red jacket.

Into the Atlantic it went. When my parents asked where it

was, I said I must have left it in the room. When it wasn’t in the room, I

suggested that someone must have stolen it. My father spent the rest of the

cruise looking for anyone my size wearing something red. Years later I told

them what really happened. Pops thought that was clever of me and shared the

story with his associates on many occasions.

Then there were the trips to Florida. To save money, my

father would drive all the way from Ithaca to Fort Walton Beach and stay at

Bacon’s-by-the-Sea, a rustic motor inn on the Gulf of Mexico.

It was in the top ten of Duncan Hines’s favorite motels at

the time, and Pops rented a two-bedroom unit with a kitchenette to save the

cost of eating out. Not because my mother loved to cook.

But there was plenty of eating out on the way to Florida,

alongside what used to be Route 1 and on side roads as well. Since it took

several days to reach Florida, Pops’s routine for sustenance was to stop at a

country store for cans of sardines, saltine crackers, and sharp cheddar, what

he called rat cheese. We ate the sardines right out of the can, and all through

his life my father enjoyed sardine and onion sandwiches.

Hardly adventures in good eating. But because we were

roughing it, it was an adventure.

When my sister was very young, she remained at home. But as

we got older, we would both go along for the ride. I have to admit that I

picked on her a lot. There was constant noise and action in the back of the

car. I remember the many times my father’s big arm would reach back over the

seat with a rolled-up newspaper in hand, and try to swat me and my sister when

we became unbear

ably obstreperous. We would both duck down on the floor of

the car until the flailing tube of newsprint withdrew.

My sister and I squabbled plenty as all kids do, but our

parents never taught us time travel by threatening to knock us into the middle

of next week, or the concept of justice, pointing out that one day we would

have kids of our own and they hoped they’d turn out just like us. But on an

occasion or two I was taught the meaning of anticipation when my mother said

“just wait until your father gets home.”

In the normal course of things, particularly while I was

still in elementary school and my father’s business was growing exponentially,

we seldom saw him at home at night or even during school breaks. He worked

through every weekend and would close his den double doors after dinner and

work far into the night. As my sister and I grew up, we saw little of either of

our parents because they traveled a great deal. In fact, with the help of a

nanny, we almost raised ourselves. My sister and I seldom ate with my parents.

We took our meals with our nanny in a room off the kitchen my mother called the

“breakfast nook.” And in later years when we were both sent off to prep

schools, and then college, we saw even less of them.

But before that there was one more instance of family time.

As Pops became more successful, he decided to buy a boat. We lived adjacent to

beautiful Cayuga Lake (the one celebrated in Cornell University’s song, “Far

Above Cayuga’s Waters”). It is about a mile across at its widest point and some

forty miles long and you can go through the locks at the end to access the

Inland Waterway. You can pilot a boat from Cayuga Lake into the Atlantic Ocean

and some pretty sizable boats have made their way back into our lake.

To most people, a sixteen- to twenty-three-foot boat would

have been adequate, but my father went all out. He bought a thirtysix-foot

Chris-Craft cruiser with a cabin area that would sleep four people and a dining

area that would feed a small army.

My sister and I thought this was great when we were young.

Our mother would pack lunches in an ice chest for the Sunday outings, her

specialty being deviled eggs, which I still like today. My father’s specialty

was carrying as many newspapers and briefcases as he could put on board without

sinking the ship.

I remember that after Pops first got the hang of piloting

the boat, after backing it out of the dock and feeling the power of the prop,

he felt his power as captain of the ship. As we neared the Ithaca Yacht Club, a

sailing regatta was in full force. My father spotted the uniform line of white

sails racing down the lake around the buoys that marked the course. He thought

it would be fun to show off his new prize and stir things up, not realizing

that sailboat competition was mighty serious on Cayuga Lake.

Our thirty-six-foot “stinkpot,” as the sailing crowd calls

anything with a motor, plowed into the racing sailors, cutting off wind and

causing sails to droop and boats to topple. My fa

ther thought it was great fun. He interpreted the waving

fists as friendly waving hands, having no idea that he had just blown out a

championship race. He was blackballed from joining the Yacht Club for a year.

On a few occasions we spent the night on the yacht, and I

remember one night Pops anchored too close to shore. I was the first to wake up

the next morning to the sound of girls’ voices and laughter. I pulled myself

out of the bunk and went out on the back deck in my underwear to see what was

going on. Standing in my jockey shorts, I realized that we had grounded at the

Girl Scout camp and I was suddenly on stage in front of girls my age. While my

father appealed to them to push the boat out enough from the shore so he could

crank up the engine again, I retreated deep in the cabin, hoping none of them

had recognized me.

Boating weekends were exciting enough while my sister and I

were young. But after a couple of years both of us got tired of spending the

whole day on the lake, sitting around while our father read newspapers and

plowed through his work. The fun faded as we cruised the lake at low speeds

while he worked, and we made up every kind of excuse not to go out with him on

Sundays.

Father’s unique use of newspapers did not add to the

aesthetic aspects of voyages in the boat or travel by car. Aside from using a

rolled-up newspaper as a swat, he was also an obsessive newspaper consumer, and

once read, they were quickly disposed of, no matter where he happened to be.

One of his acquaintances recalls a Sunday outing on the boat, by then piloted

by a hired hand. “Park sat in the back taking the sun and reading his papers

and throwing them over his shoulder. What he didn’t realize was that the papers

were going into the water. I mean he was throwing them all over the lake.” The

lake patrol noticed his papering of the lake and pulled up to the yacht and

gave Pops a ticket. According to this friend’s recollection, my father sold the

boat the next day.

My father would have a good laugh at the story, saying,

“Well, that’s a good story, but that isn’t exactly right.” He said that the

part about the newspapers going into the lake might be true. The truth is he

sold the yacht after we all got tired of cruising around in his floating

office.

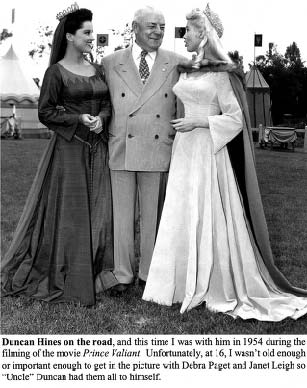

A WIDER WORLD I was twelve years old when I met the

legendary Duncan Hines. My father described him as being like “the glamorous

uncle a lot of families have. The uncle who would travel around the world and

live the good life, go to all the best restaurants, and come home to tell the

family how good it all was.” I remember the first meal with Duncan and his

wife, Clara, at our home in Ithaca. Hines’ first wife of thirty-three years,

Florence, passed away in 1938, and it wasn’t until 1946 that Hines took a

second bride. Clara was an effervescent conversationalist who, I felt in our

first meeting, didn’t particularly care for kids.

Aside from seeing Hines as the romantic, roving uncle, my

father saw him as a personable, charismatic, and photogenic man who loved to

travel, enjoyed eating, and was easy to like. Pops maintained that the large

portrait of Duncan Hines that dominated his office captured the honesty,

integrity, and ruggedness of the man. He said this man lived well and had, in

turn, taught him how to live. “He had a flair for showmanship, and he had the

brains to figure out a need and fill it.”

At this first meeting, the Hines charisma had little effect

on me. He struck me as a grandfatherly figure with an outwardly pleasant

demeanor. But as I learned later, you didn’t want to disappoint him or get him

mad. When he started carving the turkey, the first thing he did was place one

of the huge drumsticks on my plate. I’m sure he thought all children liked

drumsticks, and that he was being kind by serving me first. I was horrified. I

had always detested the dark meat of turkeys and chickens. When I looked at the

dry, unappetizing leg on my plate and started to say something, I received a

swift kick under the table from Pops. This meant shut up, eat it, and look like

you’re enjoying it. I ate it, but didn’t enjoy it. That part was impossible to

fake.

Roy H. Park, Jr.______________________ 79

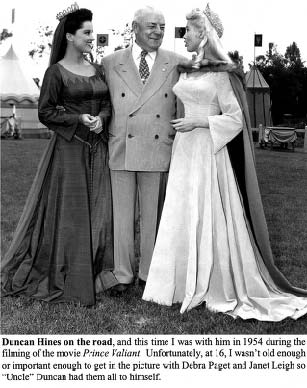

I got to know Hines a lot better later in, of all places,

California. Travel during the years my sister and I were growing up was

strenuous for all concerned, in part because of sibling rivalry. Our parents

learned early on that traveling with two squabbling kids was not peaceful, so

they would alternate us on their business trips. I remember one time my mother

told me after they returned from a trip with my sister that she asked her,

“Wasn’t it wonderful to have such a peaceful time without your brother picking

on you?” To which my sister replied, “I kind of missed it.”

For the next seven years, my parents took to the road with a

vengeance, accompanying Duncan and Clara Hines to promote the food products.

The quartet took their dog-and-pony show to hundreds of towns, going on radio

and television, persuading mayors to proclaim a “Duncan Hines Day,” and

autographing the Hines books in Hines-recommended restaurants. Television was

just starting up, and Hines was a natural entertainer, so he got a lot of

airtime.

The “Day” conc