CHAPTER 5: TO FRESH WOODS AND PASTURES NEW

Tomorrow to fresh woods and pastures new.

—John Milton To fully acknowledge John Milton, this chapter

title would begin with “Tomorrow.” For me it was yesterday. During the three

years I spent in New Jersey at the Lawrenceville School (although the thought

did occur to me it was a way to simply eliminate me as an encumbrance to my

parent’s travels), I did miss home. Having gone through the first year of high

school in Ithaca, I missed my friends and my female counterparts at Ithaca High

School, since Lawrenceville was not coeducational at the time.

The school did have a number of proms and other get-togethers,

to which I invited some of my former Ithaca girlfriends. My Raymond housemates

and I also watched the predecessor of MTV, American Bandstand, and since the

high school girls who appeared on the show lived in nearby Trenton, New Jersey,

we had a regular pen-pal party going. A number of them were invited to the

Lawrenceville proms.

During this time, I lost track of what my parents were up

to, but my mother and father kept close track of me. I had read J.D. Salinger’s

The Catcher in the Rye, which was published around the time I was in prep

school, and I managed to prevail on my father to let me and two of my

classmates spend a weekend in New York City. We stayed at the New York Athletic

Club, which had for the first time decided to allow women in the dining room,

but still not the rest of the areas in the club. My classmates saw the New York

trip as an opportunity to smuggle any receptive woman they met on the street

into the club, alas without success.

So we took this as an opportunity to kick off our drinking

career. I remember the night after our healthy indulgence attending a first-run

movie. Back then a “first-run” movie was equivalent to a Broadway show. It was

a full house, and we had seats in the front row of the balcony. I was,

unfortunately, more sick than drunk, and I finally lost my dinner over the

side. The recipient below was smart enough to track me to the men’s room after

he found the seat empty directly above him, and went there to clean off the

results of my evening. I have seen this in many movies since, and I’m sure I

was not the first to close the stall door and stand on top of the toilet to

avoid being spotted when he looked under each stall. That is where I heard,

during his cleanup, most of the swear words that would stand me in good stead

for the rest of my life.

I made the mistake, during a Thanksgiving break, of telling

my mother about some of the things that happened in New York, and she started

referring to The Catcher in the Rye. She asked me questions even the author hadn’t

thought about.

Assuring her that I avoided women of the night during this

trip, I was also assured by my parents that it would be the last trip I would

take to New York during the remainder of my Lawrenceville stay. My father had

always feared a paternity suit, something that he might have to end up paying

for. So he kept a watchful eye over my escapades even into my college years.

This monetary concern kept my youth fairly tame, although I attracted and was

attracted to some very good-looking and active women in the two colleges I

would later attend.

Other than this, for the most part I stayed out of trouble

at Lawrenceville. Back then (and still now), I did not go to bed before

midnight. Late night was when I did most of my studying, and, I might add, my

best work. Unfortunately the lights cut off in the dorm around 10:00 pM, and

it’s hard to sit at a desk and study while you’re holding a flashlight. So I

rigged up a device with an eight-volt battery wired to a light over the desk.

The problem was to avoid being caught with a light on, so I wired the battery

along the baseboard and the back of the door to the door latch so that when the

knob turned, it broke the connection with the battery.

One night the dorm counselor spotted the light in my

second-floor room from the ground outside and crept upstairs to check it out.

When he quietly twisted the knob to the door, it cut off the light, leaving me

sitting in the dark at my desk. I told him I had a waking dream and was

sleepsitting.

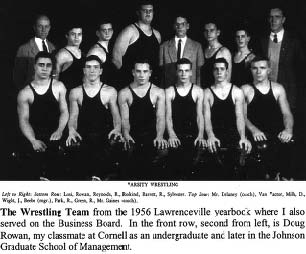

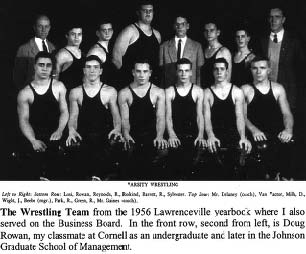

At Lawrenceville, I met classmates with whom I have stayed

in touch through the years. One was Doug Rowan, who later was in my class in

what is now the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell. We were both

varsity wrestlers at Lawrenceville, and some of my best memories are there.

Wrestling creates ties that bind. During the season, we ran five miles a day,

worked out in the gym, and practiced day after day and weekends. I represented

the team in my weight class, but I wasn’t the only one trying out. We all had

backups in our weight class, and I had to wrestle off with mine before every

match for the privilege of representing our team.

One of my opponents had both a psychological and a physical

advantage over me, since he was born with only one arm. Now you might think that

someone with two arms could easily beat someone with one, but it was not true

in this case. At least not in collegiate wrestling which is quite different

from professional wrestling.

In the mat position that starts a match, a right-handed

competitor on top has his left arm around the opponent’s waist, with his right

gripping his opponent’s right arm at the elbow. This guy’s single arm was on

the left side so there was nothing to grip. You were off balance to begin with,

and during the match, he also had 25 percent less to hold on to. He was as

quick as lightning, and to compound things, his left arm was the size of a leg.

I managed to prevail once I got over my sympathy for him, and represented the

team in most of the matches.

I’m not sure there are many sports that cause so much per

sonal uneasiness and deprivation before the “game is on.” In

wrestling, you are part of a team but not part of a team effort. It is a

distinctly individual sport. The team is dependent on each member’s winning to

raise its overall score, but no supporting teammate is there to compensate for

your blunders. You are very much alone when you are out on the mat.

Most of us were a pound or two overweight for the class in

which we wrestled, so the day before the match we smelled the food we couldn’t

eat while existing on concoctions of honey and orange juice to pull us through

final weight-reducing exercises.

As night approached I sat unfocused over my homework, accom

plishing nothing, pacing the floor, or sweating in bed. Some

of my teammates had enough confidence to go peacefully to sleep, but they were

rare. Wrestlers have unpredictable ups and downs and a champ today can be

pinned on his back looking up at the lights tomorrow. Most of us knew this only

too well, and to the unfortunate roommate of some wrestlers the match was

fought all through the night with groans and technicolor nightmares.

When the morning came our stomachs were as empty as a

fraternity keg at midnight. We sat in the swaying bus headed toward our

opponent’s school, eating just enough chocolate to keep energy going. Some of

us were convinced we were doomed to wrestle reincarnated Roman gladiators. We

had been filled with propaganda about the crushing victories of our opponents.

On arrival we would tumble off the bus and get into our uniforms. Before the

matches began, the two teams would sit across from each other, each of us

trying to ignore his opponent. Your weight class is announced, you step out on

the mat, and though you may have aged a year in the last day, you could

sometimes take comfort that maybe your opponent had, too. Contrary to popular

belief, athletes who compete alone seldom hear the encouragement or advice from

their teammates, particularly in wrestling with ear guards on. Had I heard my

teammates’ advice, I would have been the top dog in my weight class among the

military and prep schools we competed against. In the final championship match,

my opponent managed to pin me with five seconds left. My teammate, Doug, had

shouted for me to simply roll off the mat to break my opponent’s hold with ten

seconds left. Had I done that, since I was ahead on points, a first-place medal

could have been mine. Overall, I won some and lost some, but the Lawrenceville

wrestling team in its 1955−1956 season boasted the best record of any team in

the previous ten years. We had six wins and two losses and retained our title

as state champions for the fifth straight year.

Aside from wrestling, I was a member of the Inquirers Club,

on the Editorial Board of the school newspaper, the Lawrence, for which I

reported and also contributed cartoons, and on the Business Board of the school

yearbook, Olla Podrida. Looking back through some graduation comments from my

classmates scrawled in the yearbook and addressed to some of my respective

nicknames of “Royus,” “Royondo,” “Parkey,” and “Roy-Boy,” I note that one of

them said, “I hope you will continue with your creative writing.”

Among the notes I also saw was, “In spite of the fact that

you referred to me as despicable, I still think you are a pretty good

guy….Maybe when you look back at the past, you’ll see that I’m not the bully

you thought.” I was a little guy and, understandably, not fond of bullies. In

my senior year we moved off campus into The Lodge, and one of my housemates enjoyed

picking on students smaller than he was. I was at the top of his list. About a

month and a half into this, I got fed up and decided to go extracurricular with

my wrestling abilities. I have my fair share of patience, but there comes a

time when I just plain tire of taking crap. This was one of those times.

It is amazing how your adrenaline soars when you really get

mad. He was unprepared for wrestling and was subjected to the best I could give

in front of his classmates, and that was the end of his bullying me. Not only

had I earned his respect but it also had an unanticipated impact on his general

behavior—he stopped picking on the other small people he had formerly targeted

as well. He could never be sure whether one of them might step up and repeat my

performance.

My years at Lawrenceville gave me not only an excellent

education, but something that lasted a lifetime—self-confidence.

In years to come, I would need every bit of it, too.

Getting back to my father’s business, by the mid-1950s

despite distribution in only 23 states, the Duncan Hines cake mixes were number

two among all brands in sales. Becoming a marketing force to be reckoned with

led directly to a merger proposal from Procter & Gamble in 1956.

I was in my senior year in Lawrenceville when P&G

approached my father and offered him a deal. Having abolished much of the

drudgery in the laundry room, P&G decided that it was time to march into

the kitchen. The Duncan Hines brand struck them as a useful wedge for breaking

into that market. I didn’t hear a lot about the behind-the-scenes negotiations,

but my father said he had arrived at a figure that he would accept, and with a

few refinements to be ironed out, told me he was going to hold to a “take it or

leave it” deal. I didn’t learn until many years later that my father’s

Hines-Park Foods operation was under financial stress. The company was

struggling because the costs of developing, packaging, advertising and

distributing the product line were not yet being offset by anticipated

revenues. Something not uncommon in a start-up business, and my father was not

dealing from a strong position.

At the time, Stewart Underwood had become corporate

secretary and general manager of the marketing division of the Duncan Hines

Institute, and owned a fair amount of stock in Hines-Park Foods. Underwood was

on his way to his honeymoon in Myrtle Beach, SC, when Pops had the state police

pull him over and tell him to go to the nearest phone to call my father. Pops

told him that P&G had made an offer and he wanted to know if Underwood was

willing to sell his shares. Having worked for my father for sixteen years and

knowing the state of business at that time, Underwood said he would be more

than happy to sell. This allowed a P&G buyout to be made without any holdout

shareholders.

I should mention here that while I was at Lawrenceville,

shortly after Underwood’s marriage, his young wife was asked by my father to

drive me from Ithaca to Lawrenceville. Pulling up in her Chrysler convertible

with a beautiful young woman made me an instant star at my Raymond House dorm.

At any rate, after the P&G offer we took another one of

our few family vacations and went into the Laurentian Mountains in Quebec,

Canada. It turned out to be an extended vacation. Pops had told the people at

P&G that he was leaving town and could not be reached, and no one was to be

told where he was. He said he would check with his secretary from time to time

from various locations, and that he would return for the closing once P&G

decided to accept his terms. We camped out in a resort completely removed from

communications, and every morning my father would go down to the nearest

village to check in with his office via the public phone. In a sense he was

truthful in saying he was in a location where he could not be reached.

The days dragged into weeks and the numerous phone calls

P&G made to my father’s secretary were reported back to him verbatim. My

father knew his terms would be nitpicked, and the P&G lawyers came up with

every twist and turn on the deal that a magician could imagine. All of which

were crisply turned down by my father’s secretary, simply saying that she had

no way to communicate these alternative offers to him.

Quebec is a French-speaking province, and although I took

French at Lawrenceville, I disliked it intensely. My dislike of and lack of

fluency in the language did not serve me well, since the girls who worked in

the resort spoke only French, but I managed to find ways to communicate.

At first I felt isolated and bored, since we stayed longer

than most guests, but I began to be welcomed at the nightly campfires for the

staff after the day was over. Sometimes I snuck back into my room in the

cottage we rented well after midnight. I was thankful my father was totally

absorbed by his work; with his attention elsewhere, I was pretty much on my

own.

I will never forget the night when one of the young

waitresses took my French version of “See you later” to mean “See you now” and

decided to follow me back to the room. Instead of a kiss good night at the

door, she slid past me inside the room. Since my parents were sleeping next

door, and my sister in the adjoining bed, I felt the visit would be

inappropriate, but it took me quite a while to explain to the girl that she had

to go. She left in a huff. Word spread among the young people I hung out with,

and they came to the conclusion there was something wrong with me. Frankly,

although I tried to explain the situation, I came to the conclusion that they

were correct. Well into the second month of our stay, my father finally

returned from his phone call in the village to say that his full terms were

going to be accepted without change by P&G, and that we could return to the

United States.

On the drive back home, I learned the price tag on the deal,

which my father promised P&G he would not publicly disclose, but he did

tell me that it would be enough to get him into whatever new career he wanted.

Although paltry compared to today’s acquisition prices, back

then it was a good piece of change. My father never told anyone what he sold

the company for, and except to say he got 360,000 shares of tax-free P&G

stock, I will keep his secret on the dollar value of the sale. The merger

between Hines-Park foods and P&G was announced on August 17, 1956, and my father

signed on as a consultant to P&G for the next six years. By the end of

1956, P&G had introduced twelve mixes into their new line of Duncan Hines

baking products from flap jacks, muffins, and rolls to brownies, coffee, and

sponge cakes. And I had graduated from Lawrenceville and was back in Ithaca as

a freshman at Cornell.

TO THE (BIG) RED AND (SNOW) WHITE FIELDS OF CORNELL One of

the first things I did after arriving at Cornell was try out for the wrestling

team which I made during the first half of my Freshman year. The opponent in my

weight class had been a fellow student at Ithaca High who had gone on to become

an Olympic champion. During tryouts I gave it my best shot and held my own

without getting pinned, but in the long run, he solemnly assured me, putting

aside any remnants of our high school friendship, “That will not continue to

happen.”

I took his word for it and along with being on a fast track

for scholastic probation, bagged wrestling as a sport. Enrolling in the

alterate standard physical education class required, I met with another

champion in one-on-one sports when I took fencing during what proved to be the

short time I survived at Cornell. My instructor was a world-class champion in

this sport, and I would, ironically, end up traveling with him (I’ll just call

him “Mr. Raul”) several years later while working in my father’s business

during a summer recess.

When I became a freshman at Cornell University, I went in

with the largest class (thirty) of graduates ever from Ithaca High School. We

have a reunion every five years and almost everybody who’s still alive shows

up. I am not sure I want to go back for my fiftieth reunion because, at the

last one, some of my classmates looked pretty old, a sad reminder of what I may

look like when I grow up. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want to risk reminding

a long-lost classmate “you were in my class.” I might be asked what I taught!

At the start of my freshman year at Cornell, I attended a then-compulsory

summer retreat for freshmen. I spotted during this two-or three-day affair

someone whose air of innocence and wholesomeness was magnetic. We started to

date in the early part of our freshman year. It was like the courtship between

a couple of fourteen-year-olds, and I treated her like she was the queen she

was soon to become. That could have been my mistake because I felt she was

untouched, if you know what I mean, certainly by me, but avidly sought after by

others.

In those days at Cornell a Queen of the Freshman Class was

crowned and the lovely young lady I considered my girl, was the one who was

chosen. I got to escort her to the ball but, a few days later, when I called

her for a date, I was unable to reach her. Every junior and senior male on the

campus, of which there were thousands, zeroed in on my angelic freshman queen

and the last time I ever dated her was the night of her inauguration. I can’t

blame her for passing me over, since she had her pick of 15,000 men at Cornell.

Sometimes you get and sometimes you get got, and I did feel foolish thinking

about the opportunity I may have missed.

Apart from being serious about her, during my freshman year

at Cornell I did everything a freshman could humanly do to avoid getting

serious about anything else. I cut classes, put my feet up, and took it easy.

Why? Because the content of almost 90 percent of my freshman courses had been

sufficiently covered, as I saw it, at Lawrenceville. In biology alone, I cut so

many lectures (in those days you received a point off for each one cut) that my

A+ at Lawrenceville turned into a barely passing 60 at Cornell.

It would never happen today, but I also had a car and a

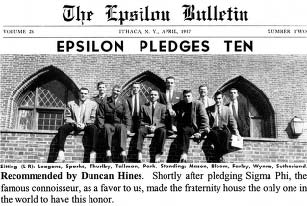

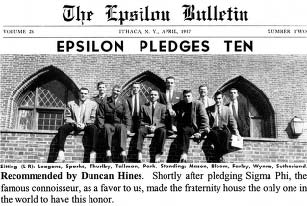

parking permit as a freshman at Cornell. Big mistake. I was also the Art Editor

of “Sounds of Sixty,” our class newsletter. I pledged Sigma Phi as a beginning

sophomore, and my fraternity membership became another excuse to play instead

of work. It wasn’t long before I was on scholastic probation, shortly to be

combined with social probation.

A number of people I had met during prep school who attended

Cornell with me, some from Lawrenceville, formed a gang of hell-raisers to an

extent unimaginable at Cornell. We pulled every stupid, mindless stunt in the

books, from filling our two-story dormitory halls with straw from a

construction site to putting work-site signs and flashing lights throughout the

building. We stole toilet seats out of the dorm and put various objects in the

beds of all of our classmates during the day while they were at classes.

That behavior, in addition to my visibly low grades (which

are supposed to go up and not down when you are on scholastic probation) put me

on the road to academic perdition. I busted out of Cornell at the end of the

first semester of my sophomore year.

Needless to say, my father was not thrilled with this, but

he did go to bat for me. He called his contacts in his home state to see if The

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill might give me a second chance. I

went down, and as a favor to my father, I was given the following scenario: If

I took two courses in Cornell’s Department of Communication Arts during what

was left of the second sophomore semester after I busted out, as well as two

correspondence courses from UNC and received at least a B average in all of

these (step one), and if I attended a double summer school session at UNC—took

four courses—and maintained this B average overall (step two), then (if I could

maintain a B average in all eight courses across the board), I would be

admitted as a sophomore at UNC. That meant I had lost a half-semester of

college, which wasn’t too bad, providing I was able to perform.

Extreme motivation is usually a product of extreme need. To

redeem myself, and to redeem my father, as well, I pulled it off and entered

the Journalism School at The University of North Carolina in 1958. Needless to

say, the motivation that I generated did not leave me and has lasted throughout

my life.

I moved in the direction of journalism because I truly liked

to write and although I did have an above-average artistic talent, I knew I could

never begin to make a living at it. Journalism was not a deliberate choice

because my father started out in it, but I would have to think that genetics

played a role. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

One of the courses I took at Cornell during this period was

creative writing, and as a class assignment, I convinced my professor, William

B. Ward, that I should write an article on why I busted Cornell. He was

lukewarm to the idea, and after it was completed, it earned a C+. Fortunately,

the rest of my articles were not affected by this low mark, and more as a

challenge than anything else, I began to submit this article to magazines.

I will never forget when I received a call from one of the

editors at Seventeen saying they liked the article and asked for my permis

sion to run it when the magazine had a “hole.” Without

telling my professor, I gave the editor permission and kept my fingers crossed.

About two months later I received another call saying they

had a hole to fill, but they would have to “judiciously” edit my article to

about half its length to fit, and said that if they couldn’t do that I would

have to wait until a bigger hole in a future edition. I took the chance, signed

off on the release, and a month later the article appeared in the October, 1959

issue of Seventeen. As a feature in the issue, they even hired an artist to

illustrate, cartoon style, the events that led up to my Cornell demise. I think

one of the most satisfying things I have ever done was telling Professor Ward

his low-graded article had been published.

Not only was the article a success, but the your Letters

section of the December issue of the magazine was dominated by letters from

kids around the country praising the article. I also received several pounds of

fan mail at The University of North Carolina from students simply addressed

with my name at UNC. I later was told that the magazine, itself, had also

directly received many letters that, regrettably, they had thrown away, so I

never saw any of them.

Needless to say, this case history was used in the class

taught by my professor at Cornell right up to his recent retirement, as an

outstanding example of how to succeed in creative writing. It was headlined why

i Busted CoLLege. For those inclined to read this, my first major piece of

confessional journalism, I have reprinted it, warts and all, but with enduring

pride along with student comments in Appendix A in this book. As the saying

goes, when you have a lemon, make lemonade.

Of special note was the letter published in the December

issue of Seventeen from Cornell Associate Dean Rollin L. Perry, which read: “I

want to say how much I enjoyed the article by Roy H. Park, Jr. I was very close

to Roy and his situation here at Cornell and believe he has done a straightforward

and sincere job of writing of his experience. Nothing but good can come from

such honest reporting.”

(Back to Contents)