BEFORE MY TIME

Where I was born and where and how I have lived is

unimportant. It is what I have done with where I have been that should be of

interest.

—Georgia O’Keefe

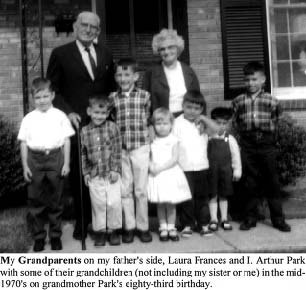

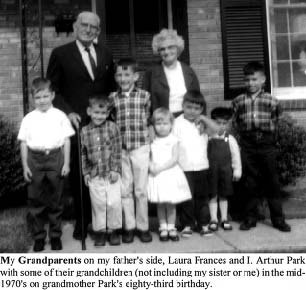

My father was born in Dobson, North Carolina, on September

15, 1910. The youngest of four children and the second son of Laura Frances

(Stone) and I. Arthur Park, Roy H. Park started life on a prosperous farm in

Surry County near the Virginia border northwest of Winston-Salem, NC. This was

unfortunate, since he detested farm life from an early age. I have heard that

he did everything he could to avoid the labors involved with farming, even

taking up reading the Bible before he reached his teens. This put him under the

protection of his mother, the daughter of a Baptist preacher, and he was able

to avoid much of the work in which his father and older brother were engaged

that was required on a farm. Whenever his father commented on his absence in

the field, his mother would tell her husband to leave their son alone because

he was studying the “Good Book,” and that was more important than pitching hay

or shoveling manure.

He was, therefore, highly motivated to leave farm life as

soon as he could. It was said that he came down with pneumonia in December of

his first year of high school and at age thirteen, spent the rest of the year

in bed with what his doctor diagnosed as rheumatic fever. His mother, a former

schoolteacher, believed that an idle mind was the devil’s workshop, so she kept

him busy with lessons sent from school. He returned to Dobson High School in

the Surry County seat, some fourteen miles north of Elkin, the next fall. He

took a test to see if he could rejoin his classmates and did so well that the

school allowed him to skip a grade.

In high school he also delivered newspapers, and worked as a

county correspondent for three weekly newspapers. His hustling drive, coupled

with skipping a grade, enabled him to graduate from high school in 1926 at age

sixteen. That same year, he headed “down east” to get a higher education, with the

idea that he might become a physician. He first applied to Duke University,

took the entrance exam, and was offered a scholarship.

But Duke lost a potential medical student when my father’s

brother, who by this time was a student at North Carolina State College in

Raleigh, drove over to Durham to see him one day. He was driving a fairly new

Chevrolet Roadster, and told my father if he transferred to State, he’d let him

drive the car every now and then. So as one of the youngest students to attend

NC State, at age sixteen he enrolled to study business and journalism, and

worked, while attending classes, to put himself through.

“My father was a farmer, but my oldest brother graduated

from State and my two sisters went to Woman’s College [now The University of

North Carolina at Greensboro],” my father recalled. “I knew that if I needed

help from my family, it was there. But I always felt that if you could maintain

your independence, you could take great pride in it.” I was later to learn the

truth in that.

There is one thing many people don’t know about the

journalism courses in which my father enrolled at NC State. I found it in my

files among the many copies of my father’s talks and speeches, some with his

notes or alternate comments scribbled along the margins in his awful

handwriting. It was part of his acceptance speech when he was inducted into the

North Carolina Journalism Hall of Fame in 1990.

Stretching things just a bit, he called The University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hill his alma mater, saying in a speech he gave many

years after graduating that, “Of course I am a graduate of North Carolina

State…but when I began college, this School of Journalism was on its campus

over in Raleigh…and didn’t move to Chapel Hill until after my senior year. “Although a coincidence, not a trade, when

about the same time the Engineering School was moved from Chapel Hill to the

Raleigh campus, my father went on to say: “It was the kind of trade that makes

both parties winners….I don’t have to tell you that The University of North

Carolina School of Journalism is among the best known journalism schools in the

country…and I am proud to consider myself an alumnus of this School of

Journalism.” My father concluded his speech saying, “In fact, my son, Roy H.

Park, Jr., and his son, Roy H. Park III, are both graduates of this School of

Journalism.” (In 1990 the president of The University of North Carolina, C.D.

Spangler, Jr., wrote him a letter saying, “I am proud that two great

universities within UNC can lay claim to you. Your comments about the

Engineering School at UNC-Chapel Hill and the Journalism School at North

Carolina State University convince me that I would benefit from a brush up on

the history of the switch.”)

Geography aside, at North Carolina State in 1926, even the

$150 yearly tuition and $16.50 a month for food was a lot of money for someone

who didn’t have any, and I suspect that’s when my father’s real work ethic

began. Although I share my father’s passion to work hard, he was as true a

workaholic as ever existed.

In his junior year, he was out driving with his friends one

evening in the early spring and he ran into a parked car. He decided that

rather than go home for the Easter break, he would get a job to pay to fix the

car. I suspect that this reflected his penchant for work, and his decision not

to spend the break at home also kept him off the farm.

One of the ways he earned a few bucks, along with a fellow

student with the unusual and unlikely moniker of “Pea Vine” Reynolds, was to

sell magazine subscriptions. My father said many times the woman of the house

would not come to the front door, but would call down from an upstairs window

or porch to ask what they wanted when the door bell rang. My father’s answer

was “COD, lady,” which would bring the prospect down to the front door. When

they discovered a delivery was not being made, Pops would meekly say that COD

meant, “come on down,” and then go into his routine about being a poor student

working his way through college by selling magazines. Most of the time it

worked.

Reynolds, at age seventy-nine, said in a telephone interview

from his Lumberton, NC, home, “Roy’s got what you might call a broad viewof the

future. An’he figgers things better ’n any man I ever seen.” Both Reynolds and

Park must have done some fancy “figgering” because Reynolds says of their

magazine hustling, “I started in [college] with two hundred dollars. I paid all

the tuition myself, all the costs and finished with a new car, two thousand

dollars in cash, and that was in the middle of the Depression.” Pea Vine and

Park went their separate ways after gradation in 1931, but kept in touch, and

years later he would come back into my father’s life.

Because my father had worked as a reporter for the campus

publication the Technician since his freshman year, he was able to find a

part-time job as an office boy with the Associated Press in Raleigh. He

operated a mimeograph machine, stuffed envelopes, and ran errands for $4.50 per

week, attending classes until noon and working afternoons for the AP.

He also wrote fillers for area newspapers (at 10¢ a column

inch), and kept pestering the Raleigh bureau chief, W. Joynes McFarland, to

“let me write some real stories.” After he threatened to go home to Surry

County “because I couldn’t live in Raleigh on four dollars and fifty cents per

week,” McFarland found a spot for him on the AP staff.

Working with the Governor’s Office, Raleigh newspaper

publishers, the college extension editor, and others, his wages grew along with

his responsibilities, including correspondence for two northwestern North

Carolina newspapers. Another of his duties was covering executions by

electrocution at Central Prison. “Nobody liked doing that,” he said, “so we’d

get ourselves a Coke with some ammonia in it before we went to the prison. And

sometimes we’d put in something a little stronger. I thought it was very

foolish at that time to sit there with a clock and see how long they

struggled,” he recalled. “It was pretty bad. It gave me nightmares.”

By 1930, at age nineteen, my father had earned enough

credits to graduate, and was making a stately $18 per week at the AP.

He said the money was not as important as contacts with the

influential people he got to know, but it helped pay for school. And these

contacts were to prove helpful as graduation approached.

But he decided to enroll in graduate studies so he could

serve as the Technician’s elected editor-in-chief. Jobs were scarce, and the

position paid a salary of $37.50 a month plus one-fourth of the profits. “This,

plus freelancing for out-of-town newspapers, paid better than the few dollars a

week I would have received as a newspaper reporter in those days,” he said.

I don’t want to leave the impression that my father’s

college life was all work and no play, since he did take time to relax and have

fun. He said he had two old cars. “That was so I’d be sure one was always

running. I’d park them on a hill so I’d be sure I could get them started. One

was a Willys-Overland—that was the fancy town car,” he said.

In 1931, my father was honored by his senior classmates as

“best writer.” As one of 311 in his June graduating class, with a minor in

journalism, he was among 37 to receive a BS in Business Administration from NC

State. His college annual, Agromeck, predicted that he would be “a lord in the

fourth estate.” It was an oddly accurate prediction for a college annual, but

in forty years it came true.

But back then it was the beginning of the Depression and

jobs were scarce. Planning ahead, my father had been reading the want ads long

before he graduated. As they say on the farm, timing has a lot to do with the

outcome of a rain dance, and it makes sense to go after a job when one opens up

that you might be able to get.