A TOUGH INTERVIEW

One day he saw a blind ad for a public relations job in the

Raleigh News & Observer. It was signed Box 731, which was located in

Raleigh’s historic Century Station. Instead of mailing in his application, he

hand-delivered his response to the postmaster in a colored envelope to make it

stand out, then stationed himself in front of the box the next morning to wait

for the person who came to pick up the mail.

Eventually a man came in to open the box, and my father

eased over to introduce himself, pointed to the pink (sometimes he said it was

blue) envelope, and asked if the owner of the box would kindly read his

application first. The man turned out to be H.B. (Red) Trader, the secretary to

Uria Benton Blalock, head of the Farmers Cooperative Exchange as well as the

North Carolina Cotton Growers Association, one of the largest cotton marketing

associations in the South.

Before the day was out, my father was able to call on his

earlier contacts from the Governor’s Office to the president of NC State to ask

them to make calls on his behalf. Before the sun went down, Blalock had

received telephone calls endorsing him from O. Max Gardner, governor of North

Carolina; Josepheus Daniels, publisher of the News & Observer; John Park,

publisher of the Raleigh Times; the NC State president; and three other influential

local men. This made it difficult for Blalock to avoid asking my father to meet

with him. As my father later told an interviewer, “My letter got a favorable

response. Anticipating that it would, I had bought myself a white cotton suit

and showed up for the interview wearing it.”

The job was director of public relations, which involved

editing and publishing a newsletter, the Carolina Cooperator, for co-op

members, and my father felt it was a perfect match. But the job offer was not

immediately forthcoming.

At their meeting, Blalock said, “Look at all these letters.

I’ve got letters from people with a lot more experience than you have. I’m

going to hire another candidate, but I wanted to tell you that I was impressed

by your initiative. If you keep going like this, maybe one of these days you’ll

amount to something.” My father replied that he wanted to amount to something

then, and Blalock did not immediately turn him down.

Instead, he took my father, who was still a student, along

with him on a business trip to Kannapolis, NC. It was hot in Blalock’s Lincoln

limousine, and they would occasionally stop for a cold drink along the way. My

father said Blalock would ask him to call the office and tell them to sell so

many pounds of cotton, or buy so many. He’d write it all down and call it in,

but thought it was one hell of a poor company to work for if they were spending

money buying futures on this and that, with a fellow like him telling them what

to buy. My father soon guessed, however, that Blalock was just finding out how

many mistakes he would make. A few days later, Blalock called my father into

his office to repeat the bad news. He told him, “You’re a pretty smart and

resourceful young man, but you’re too young. You ought to stay in touch, and

after you learn something about journalism maybe we’ll have a place for you.”

But my father didn’t give up. He told Blalock he’d saved

some money and said, “I know I can do this job. I’ll bring my own typewriter if

you’ll give me a place to put it and a lamp. You don’t even have to give me an

office. And I’ll work for free for three months. If you don’t ask me to stay,

I’ll come by and thank you for the experience I got and go on my way.” “We’re a

large organization and can’t do that,” Blalock told him. But then he thought

for a moment and asked my father what he figured the job should pay. My father

replied, “I think it’s worth two hundred and fifty dollars a month.”

To which Blalock said, “You’re the damnedest young fellow I

have ever seen. I’ll give you a hundred dollars a month.” My father responded,

“You talked me into it.”

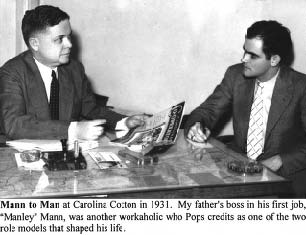

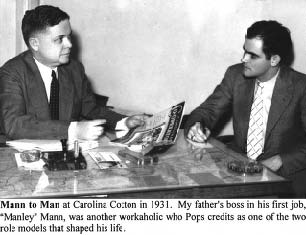

Thus began my father’s first business career, thirty days

before his graduation. When he reported for work, his direct boss at Carolina

Cotton was M.G. “Manley” Mann. My father credits him as one of the two people

who gave him a role model for success, the other being his future partner

Duncan Hines, who was internationally famous as an arbiter of taste. A tough

taskmaster, Mann was another workaholic who expected work to be on time and

done right. My father said Mann was good at business, but he liked him because

he said he was also a dreamer, and that was something they both had in common.

My father always felt it was OK to have dreams, as long as you were able to

work hard enough to put a foundation under them. And he was good at that.

As director of public relations, my father stayed with the

Cotton Association for eleven years in public relations, advertising and speech

writing. He impressed his employees and their growing number of customers with

his flair for creative editing and his skills in public relations and sales

promotion. There was a lot of money in cotton in those days, and one of the

more remarkable things he did was figure out a way to enhance the public image

of cotton garments. As the traditional fabric of work clothing, being tough and

comfortable, it was favored by the working class, and looked down upon by the

socially elite and those who wanted to be. My father figured that if he could

change that image he could substantially broaden the market.

He came up with the idea of holding Cotton Balls, highly

publicized statewide affairs, which included parades and formal dances attended

by the daughters of some of North Carolina’s most prominent families. The

promotion included “Maids of Cotton,” young women dressed in all-cotton gowns.

Park arranged for the manufacture of special gowns for the women and tuxedos

for their escorts, and all in attendance wore cotton.

Including the lady who would become my mother, Dorothy

Goodwin Dent.