Fact-finder. The Fact-finder role may be charged with assembling competitive specifications for the different ERP vender's products. Another role might be a Delphi Process Coordinator role which would interview the company's subject matter experts using the Delphi Process to normalize and improve the in- put.

Extending the Model

In high risk, highly contentious or long duration decision-making the deliberative phase of the decision-making process may be best structured as its own team. This will help keep the decision-making process roles and responsibilities from becoming entangled with roles and responsibilities in the wider team context. The additional clarity will improve the wider team's functioning, including the implementation phase of the decision.

When a team takes this approach it is creating a sub-team and should follow the typical steps of identification, goal-setting, roles definition, and so forth.

Section 4

Criteria

In This Section

1. What Are Criteria?

2. How Does Criteria Analysis Work?

3. How Simple Can This Be?

What Are Criteria?

Criteria are requirements.

In goal-setting, criteria describe acceptable threshold values for outputs. For example, a goal of reducing defects per million parts might be 20%. If the team reduces defects by any number greater than or equal to 20% they are successful.

In decision-making, criteria are used to select among alterna- tives. So to continue the example, if the team needs to select a Lean consultancy to help the effort, the number of associates located in the Midwest might be a criteria. That criteria might have a cutoff threshold value, or it might not.

In this example, the decision criteria helps select an input that will help achieve a goal criteria. However, the input criteria and the output criteria are not directly comparable.

How Does Criteria Analysis Work?

In decision-making, multi-criteria analysis requires the team to identify what will best lead to a successful implementation. That is to say, what factors of the decision improve the team's chances of meeting its overall goals. As these factors are identified, the team draws up a ranges of values, possibly including thresholds. The factors and their value ranges are criteria.

There are many approaches to multi-criteria analysis. Some use hierarchies of criteria. Other approaches use different crite- ria comparison techniques, including weighting, pair-wise analysis and other methods. In some cases the process emphasizes quantitative measures, while in others relative or rank ordering may be sufficient.

Likewise, teams may approach setting alternatives' criteria val- ues in different ways. Some of these include:

• Using independent external sources

• In an open collaborative process similar to caucus voting

• Using a discrete approach like the Delphi Process or one that is similar to a secret ballot

• Selecting the most expert member or members of the team to to assign a value to each criteria

Which approach works best will depend on the team.

One of the more important considerations is that team set its members expectations for the approach early. The team should do this before selecting a decision to work on.

How Simple Can This Be?

Most teams make more decisions then they realize. Most of those decisions are small and efficient.

In many decisions the need for efficiency doesn't preclude using criteria analysis. However, it does argue for using the simplest elements of criteria analysis for the majority of decisions.

Hierarchical criteria, pair-wise comparison, criteria weighting, the Delphi Process, and other detailed approaches are all candidates to be skipped in the majority of cases.

Instead, the bulk of decisions may require nothing more than:

• A clear itemization of criteria

• Simple ranked or comparative values

• A consistent, collaborative value setting process

Section 5

Ranking

In This Section

1. Why Is Ranking Decisions Important?

2. How Do We Rank Decisions?

3. Ranking Alternatives

Why Is Ranking Decisions Important? Teams rank decisions to identify the highest value decisions. Teams face decisions with different levels of importance. A team may need to focus on a few decisions to the exclusion of others.

The best return on time spent may not be obvious. Moreover, different team members may see the relative importance of deci- sions differently. This can easily lead to friction, lost time, and possibly a poor use of the remaining decision-making time.

How Do We Rank Decisions?

The more consistent the ranking process the more likely team members will accept it decision-by-decision and the more easily the decisions will be evaluated for importance.

There are many approaches to ranking. All of them attempt to remove the gut feeling approach.

The most common approach is for team members to apply a simple questionnaire to every significant decision. In order for ranking to be minimally distracting the questions should be:

• Applicable to essentially all decisions

• Simple, few and quickly answered

• Consider all important axes

Clearly these are somewhat competing objectives.

The five most common types of questions address the follow- ing:

• How quickly is the decision required

• What is the cost of being wrong

• How many other decisions does this decision impact

• Will we know if we made the right choice

• What is the value of being right

There is some overlap in these questions, particularly in the cost and value questions. In addition, they may not be equally helpful for every decision. However, they cover the majority of decisions and can be answered reasonably quickly.

Ranking Alternatives

Ranking also happens within many decisions. Frequently the alternatives in consideration are few enough that ranking them is not worthwhile.

In some case ranking is more important. This is generally true when:

• The number of alternatives is large

• The differences between alternatives are not clear cut

• Multiple choices will be made as part of the resolution

In those situations the team needs to use at least one ranking method. As with other aspects of the decision-making process, teams should identify the method in advance of needing it. And like all team activities, the method should be as simple as practical.

Some of the more common alternatives ranking methods are:

• Criteria analysis

• Voting

• Estimation calculations

• Averaged numerical rank

Criteria were covered in an earlier section of this chapter.

Voting

Voting typically takes the form of:

• One member one vote, or

• Zero or one votes per member per alternative

Other voting options include:

• Public or secret ballot

• One voting time or a prolonged open poll

• Single cast or a votes that are changeable

• Multiple rounds of voting

Clearly the number of possible configurations is much larger than most decisions require. The simplest straw poll is often the best.

Weighted Estimates

A weighted estimate usually is done by canvasing team members or subject matter experts for an estimates of the value or rank of alternatives.

One approach is to use a formula. A well-known example is PERT estimation. PERT is a project management technique. A PERT estimate is done by:

1. Asking for the low, high and most likely values

2. Adding low, 4x most likely and high

3. Dividing by 6

Average Numerical Rank

This is perhaps the simplest approach. It sums the one to N ranking of each alternative by each member to find the overall ranking.

Section 6

Cause and Effect

In This Section

1. Why Do We Make A Decision?

2. Implementability and Implementation

Why Do We Make A Decision?

Teams make decisions in order to make progress against their goals.

It is not uncommon for specific decisions to become disassoci- ated from their goal. This mainly happens due to the decision- making process not providing explicit links to a decision's cause.

Fixing the problem of disassociated decisions is relatively easy. All significant decisions should be documented both to facilitate deliberation and for future reference. Extending that practice to clarify the goals driving the decision-making process requires just two things.

First the team needs to clearly document the cause of deci- sions. Second, the cause link needs to be integrated with crite- ria, voting and other activities. Basically, the decision-making process needs to be explicitly aligned with goals, and the mem- bers need to be regularly reminded of the goals.

This may seem like a too obvious problem and a trivial solution. However experience says that a surprising number of decisions become fully unglued from their cause. Even more have one or a few members become distracted from the reason for the decision-making effort.

Implementability and Implementation

Decisions are decided to be implemented. That statement may also sound obvious. However, in some cases, some or all of the participants to a decision may not keep this in mind.

The reasons for this include:

• Decision-making that has become fractious causing partici- pants to settle without focusing on implementation simply to extricate themselves

• Participants moving on to other issues

• Participants wishing for implementation to fail for some rea- son

• Designing a creative resolution may have become the object for some participants

• The participants may not be including implementation factors in their thinking or criteria

Some aspects of the need for of implementability are similar to the concept of design for constructability in the building industry. But in decision-making the outcome can be relatively worse. This is in part due to the sometimes abstract nature of decision– making output. In decision-making the team can not create a definite blueprint, resulting in a more difficult assessment of implementability.

Once getting to an implementable resolution, teams need to re- main aware of the chain of events of decision-making. Success- ful implementation requires that a team not only keep an eye on the resolution, the immediate cause of the implementation effort, but also the original goal.

Without care, the chain of reasoning may become distorted. The effect is much like a string can telephone relay that tends to distort a message as it hops from station to station.

The approach to maintaining clarity during implementation is similar to the approach a team uses to maintain the link be- tween goal and decision-making. It is:

• Clear documentation, and

• Repeatedly reviewing cause and effect, as needed

Section 7

Implementation

In This Section

1. Some Suggestions

2. Address Decision-making Explicitly

3. Take the STAIRS

4. Be Ready To Integrate

5. A Project Managers Perspective

6. Using MetaTeam

Some Suggestions

This chapter explored structured decision-making processes. It reviewed some of the elements of structured decision-making and the reasons for including them in the design of your team's process.

In this last section we offer a few quick suggestions.

Address Decision-making Explicitly

Generally it is best to collaboratively outline the team's overall approach to decision-making up-front. Teams should minimally address how the process will deal with each of areas that are discussed in the sections of this chapter. Those are:

• Grouping

• Roles

• Criteria

• Ranking

• Cause and effect

Keep it simple, but be complete. Decision-making is one of the parts of teamwork where careful specificity early on is most criti- cal to productivity.

Take the STAIRS

When the team is preparing to make a distinct set of high-value decisions you need a more specific model of how to do it. As in all things, be explicit about the model. And make sure it links into the overall decision-making process.

There is an acronym for the parts of any good model: STAIRS. STAIRS stands for:

• Stages of activity

• Techniques of analysis

• Actors' involvement

• Inputs needed

• Rules for moving through stages

If you write up this information you have a better chance of eve- ryone committing to the resolutions.

Be Ready To Integrate

There are many source of information and guidance on decision-making. We encourage you to use them. As you do consider the overall approach of each.

Typically decision-making models lean in one of two directions:

• Effectiveness

• Correctness

Effectiveness is a focus on creating an implementable decision. It is concerned with participation, commitment, and other human factors.

Correctness is a focus on creating the optimum decision. Its concern is finding the best alternatives, using rational analysis to choose between them, and using other decision sciences tools and techniques.

Both of these biases in technique is needed. According to the situation one or the other can be most needed. And many for- mal approaches do try to balance effectiveness and correctness. But you should be ready to integrate the two from the best approaches you can find, as needed.

A Project Manager’s Perspective

If you are PMI-oriented project manager you are familiar with mapping out the inputs and outputs, and tools and techniques, of your processes. In that case, you may want to put decision– making on the same footing that the PMBOK puts Risk Management.

We discuss risk management in the chapter on risks. In that chapter we make the case that risk management is a specialized form of decision-making.

Not only is risk management a specialized form of decision- making, but decision-making as a process is likely to be more complex than risk management by virtue of:

• Greater breadth of scope

• Greater ambiguity in many decisions, and

• Less well-known roles and approaches

Treating decision-making as a project management process means identifying its inputs and outputs. Using Risk Manage- ment as a guide, we can make suggestions. The inputs you might use include:

• The Risk Register

• The RAM

• The Scope Baseline

The outputs may be:

• A Decision Management Plan

• A Decision Register

• A Decision Log

• Updates to the RAM

Using MetaTeam

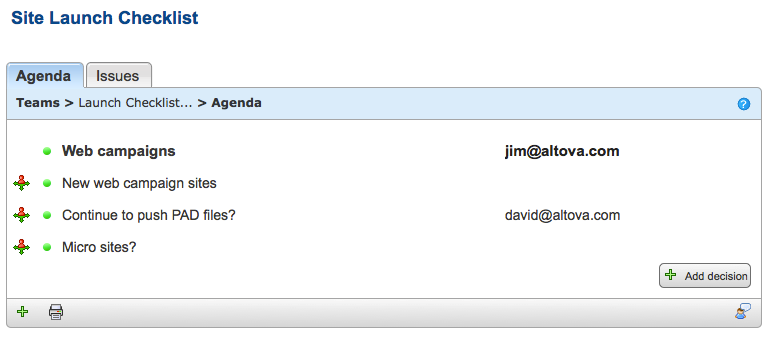

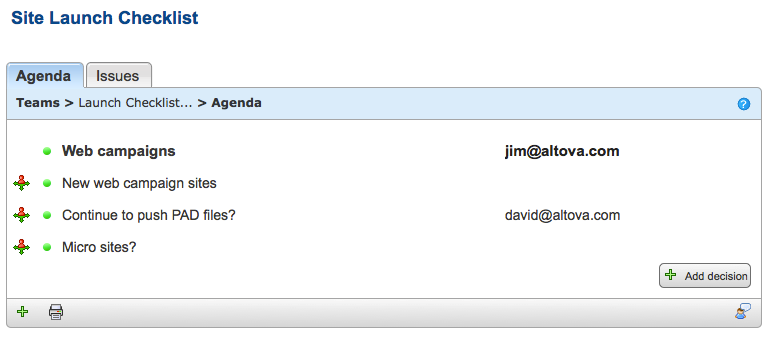

To use MetaTeam to implement structured decision-making start by doing the following:

• Log in

• Select your team from your My Teams page

• Click the Decisions button in the top nav bar.

• Click the Add link at the bottom to create new agendas to group your decisions.

• Within an agenda, click the Add link to create decisions.

• Click a decision's name to open it.

• Notice that you can add alternatives, set the decisions rank, add criteria and use the collaboration tabs within the decision, and within alternatives.

For more suggestions, tips and screenshots look in the MetaTeam blog. The Collaborative Decision-making and Multi- criteria Analysis labels are good places to start.

An agenda grouping three decisions within MetaTeam