The Leader

Who Went From

What to Why

Mario, the VP of sales at a software company, said those words to me (Jamie) three years ago.

Like so many leaders across the world, Mario believed this was a true statement. And why not? The evidence to support it seems to be all around us. Leaders everywhere struggle to build high-performing teams. Some never manage to create teams that perform at world-class levels. If they do, it has frequently come from a great deal of effort, expense, and time. But for Mario, the most compelling evidence was his own personal story as a leader up till that time—a story similar to ones I’ve heard from countless leaders.

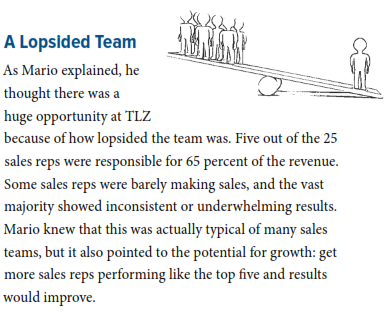

A year earlier, Mario had been a successful director of sales at an international tech company, where he had led several years of 25 percent annual sales growth for his team. That success had caught the attention of the CEO of TLZ, a large software company, where sales in one of their key divisions had been flat for a couple years. The CEO of TLZ was looking for someone to lead dramatic sales growth in that division and offered Mario the VP Sales position.

The Big Opportunity

Mario saw the move as a career-making opportunity. He believed in TLZ’s product line and thought that as a senior leader in one of their key divisions with control over building and developing the sales team of 25 reps, he could play a big part in establishing TLZ as a global leader. He also believed that as someone who had studied best practices for building a high-performance team— particularly a sales team—and who’d implemented many of them, he could deploy the right plan for turning things around at TLZ.

So Mario accepted, and after moving his young family across the country to TLZ’s head office, he quickly got to work rolling out the various strategies of his plan.

Hitting a Pothole

But Mario found it harder than he had expected to turn around TLZ’s sales team. After a year, sales growth was nowhere near his target of 25 percent. The poor results were a blow to Mario’s confidence, and to his job security.

The CEO was obviously disappointed, but was willing to give Mario more time. However, if Mario couldn’t start to improve sales in the next couple quarters, enough to demonstrate that he could hit 25 percent annual growth, he knew he would be looking elsewhere for work. Mario also knew that opportunities would be harder to find with the failure to deliver at TLZ on his record.

A Chance Encounter

Around this time, a mutual friend who had heard me speak on the latest in people performance insights suggested Mario call me for advice.

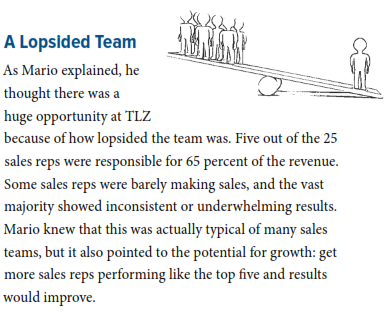

When Mario and I got together, one of the first things I asked was why he had original y thought he could turn the sales team around. What made him think there was any potential for growth?

Mario had just laid out a very simple and effective strategy for dramatically improving performance and growth in any team. All teams, sales or otherwise, have a range of performance levels—usually a small number of top performers, followed by a long tail of mid-range performers, and some low performers. Clearly, getting more top performers and more people performing closer to the top level will lift up any team. It’s the right strategy to turning around a team in a relatively short time period. However, executing it successfully requires that the leader base their plan on a full understanding about what underlies performance at work.

In order to help Mario, I needed to get a clearer picture of what his beliefs on high performance were and where he might have gone wrong. To flush these out, I asked him to tell me about his plan and what his experience had been so far.

The Best Laid Plan

Mario had two essential parts to his plan. One was simply to let some low performers go and replace them by hiring high performers. The other part of his plan was to raise the performance of everyone on the team with a number of initiatives. These ranged from improving processes, like how marketing supported sales, to upgrading or adding things like on boarding and training programs, sales support systems, mentoring, and coaching. Another key initiative was restructuring the team into differentiated sales roles—having some reps specializing in new business and others in account management.

Mario’s plan made perfect sense—bring in high performers, while also creating the structure and systems to develop high potentials into high performers.

Unfortunately, problems began to emerge early on. Some of the new hires that Mario had expected to perform at a high level turned out to be low performers. And while some of the people on his team had shown improved performance from all the training, systems, and process improvements, others hadn’t.

To deal with the hiring challenge, Mario had started to work with various vendors to help attract and recruit more top talent, including passive candidates (top performers who were open to new opportunities but not actively looking), but the problem persisted—some hires didn’t work out, and every new hire that failed was an expensive mistake. As for the strategies to improve the performance of the high potentials, he’d explored dozens of solutions— new training programs, new systems, and so on. Some seemed to move the needle a little, but he still wasn’t seeing the results he needed.

to realize that his essential problem was the time it took to find and develop the right people—and nobody could give him more time. Except his CEO, and he was already running short on patience.

As Mario explained to me, one of the mistakes he had made moving to TLZ was taking for granted how many years it took to create the high-performing team he’d had at his past company. Back then, just like every other leader building a team, he had made hiring mistakes, but he had been able to weed them out over time. It had also taken time to find out which high potentials would turn into high performers, because of course, not everyone with potential realizes it. Reflecting back on things, he realized he’d spent years creating what eventually had become a solid, high-performing team.

Now, Mario was confident in his strategy and all the systems he was implementing, but he knew that to realistically build a great team at TLZ, he’d need a couple more years—time he didn’t have.

An Information Problem

“Those mistakes are indeed common,” I said, “and for many leaders, it unfortunately takes time to gain critical information about their people. But seeing that your goal is to find more people like your top performers, obviously the information you are able to gain on these people is vital to finding more like them. So, let me ask—what information and data do you collect about your high performers? What tells you they are your high performers?”

“I look at their results, of course. Their sales numbers.”

“Is that how you identify your top performers—whoever delivers the best results?”

“Actually, no.” Mario explained that he had learned long ago that revenue alone isn’t a reliable indicator of performance. The rep who is slacking on the job could be the lucky one who answers a call from a client with a massive order. Another rep who is always making her calls and developing great relationships could have a client base in a sector that is struggling. The difference in revenue between two reps can often be a reflection of external factors and luck, and not on performance.

To see who was really performing well , Mario tracked as many performance metrics as he could—some related to quantity, like number of calls and demos; and some related to quality, like how well the sales rep built rapport with their prospects. By analyzing these metrics, Mario could clearly see who on his team was performing at a high level and who was not.

A More Honest Picture

I was impressed that Mario had identified and collected data on the metrics that actually track performance, rather than just ranking his people according to results. If you want a more honest picture of who your top performers are, it’s important to look past results into key performance metrics. Mario had done a good job here, but it raised a critical question: “How do you use this information to find others who can achieve the same performance numbers as your top people?”

Mario thought about that and said, “Well , I suppose I look for people who have performed well elsewhere.” Mario explained that when he’s screening resumes or interviewing someone, he’s digging for evidence of high performance or impressive achievements in their past.

“But when you hire people who’ve been top performers elsewhere, they still frequently turn out to be low performers for you—Sasha, for example.”

Mario nodded, saying that’s what makes it so hard to build a high-performing team.

“Your experience is typical, as I’m sure you know,” I said. “Just because someone performed well somewhere else doesn’t mean they will perform well on your team. In a poll we ran, we discovered that less than half of people who were high performers at their previous jobs turned out to be high performers in their new jobs. And these were people who had the same skills and experience as the top performers in their new company.”

“Those aren’t good odds,” Mario said, adding that they were probably his odds too.

A Critical Truth

“Mario,” I said, “when you told me the story of that rep, Sasha, who eventually disappointed you, you first referred to him as a ‘high performer.’ You used that label in a sense to define him.”

“That’s what I thought when I was hiring him. But it’s not how I would define him now.”

“Would you describe him as a low performer?” I asked.

“I would have when he was on my team, but I hear he’s joined his wife’s business and is doing a great job there. So obviously, labeling Sasha one way or the other isn’t right.”

“That’s a great insight, Mario. In fact, what you’ve described actually reveals a critical truth about high performance, which is, high performance is not a permanent quality about a person. Performance depends on the context—to a much greater degree than we would expect. In the workplace, the context is the particular job someone is doing and the company they are doing it for.

When we look at people like Sasha and label them as “high performers,” we run the serious risk of not seeing the truth, which is how much the context—the particular job and the company—mattered for Sasha to perform at a high level.

“So, what other information do I need to know?”