What the Science Says

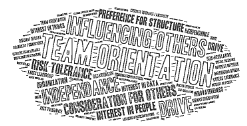

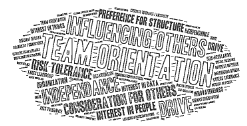

“Historical data on high performance tells us that there’s a specific cluster of core attributes that make a person who they are—attributes such as how well they recover from setbacks and their openness to change, to name a couple. Unlike performing well , these are things about a person that don’t change when they move from one context to another, or one job to another. Studies have shown that without this information, we can’t make reliable predictions about how someone will perform in a new job.”

As I explained to Mario, when we move from one job to another we leave our past performance behind, but we

“I gather you first thought Sasha had all the qualities you look for.”

“When I interviewed him, yes. But obviously not when I got to know him better.”

Psychological Traps

“Your experience with Sasha,” I said, “is a great example of a trap we’re all susceptible to called the halo effect— our tendency to think someone is good in lots of areas if they’ve impressed us in one area. For example, you might have first noticed how well-spoken Sasha was, and then begun to think he’d be good under the kind of pressure your sales reps are exposed to.”

Mario agreed and said he’d watch out for that trap. Unfortunately, we can’t really prevent ourselves from misreading people. It’s how our brains work.

“Many critical attributes are also hidden and not observable during an interview,” I said. “You might have the impression somebody is reliable because they showed up on time and answered questions well , but what happens

So one challenge is to somehow get past the limitations of human perception and ensure we get accurate, objective data on who someone is and their core attributes, prior to putting them to work. But perhaps the bigger problem is that we often don’t know what attributes actually impact performance for the job we’re hiring for. The truth is, most of us guess. And the reality is often surprising, and sometimes counterintuitive. In our research, we have found companies where the top customer service agents

Surprising Results

When I got together with Mario, I went through the results.

The data revealed several significant findings. Drive was indeed a critical attribute, with Mario’s top reps showing scores for drive well above the rest of Mario’s reps, and well above the average person. But Mario’s top performers scored quite a bit lower for problem solving than his lower performing reps—indicating that, contrary to what Mario believed, sales performance in his organization did not depend on people who were open and willing to learn and solve challenging problems.

There are certainly some sales roles where problem solving would be critical, but not on Mario’s team. In fact, problem solving might have been vital for the sales roles at Mario’s previous company, which relied on a more consultative approach, where the reps had to have a deep understanding of the customer and their problems before showing how the product could help. The top reps at TLZ didn’t have to know as much about their prospects, or solve complex customer problems. Instead, the attributes that drove their success were ones that helped them quickly build rapport and demonstrate the benefits of TLZ’s product line.

Another major insight was that every high performer on Mario’s team who was in a new-business sales role scored well above the normal range on their ability to recover from setbacks. And virtually everyone that wasn’t a top performer had a normal or below normal score for this attribute.

“I’m guessing,” Mario said, “that it’s not realistic of me to expect someone who doesn’t score high for their ability to recover from setbacks to become one of my top new-business reps.”

“The data is telling you that it’s at least very unlikely.”

Mario took a long look at the profile data of his reps and pointed out that nearly all his top reps scored well below normal for their preference for structure while his low performers had normal or even high scores. “I’ve been trying to impose more structure on the team. Maybe I shouldn’t, or at least not for my top people.”

The Power of Why

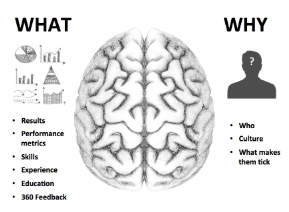

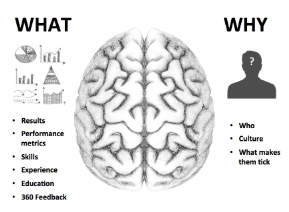

“What you are looking at,” I said, “is the data on why your reps perform the way they do. So I’ve called it WHY data. The data you have been collecting on your performance metrics to date is what I term WHAT data. In other words, you’ve been looking at what your reps have been doing— how many calls they are making, how many demos, and so on. That’s what they do. Most organizations look at this type of data; and many, like you, Mario, do a great job in this area.”

WHAT data is extremely valuable, because it can help tell you who your top performers are. But WHAT data provides only half the picture, because it can’t tell you why your top performers are your top performers. And it can’t tell you what to realistically expect from the people on your team who you might consider high potentials. It’s like using only half our brain.

The Other 50 Percent

In the same way that we need to use both sides of the brain—the rational left hemisphere as well as the intuitive right hemisphere—to perform well in the world, we need the data on what our people do as well as why they do it to know how to create high-performing teams. In a sense, WHAT data provides 50 percent of the information we need to make good decisions about people, and WHY data provides the other 50 percent.

The Three Steps to Why

Leaders who are using WHY data to build high-performing teams follow three basic steps.

Step One: Understand the Individual

The first step is to look at every individual on your team and understand their core attributes—what makes them tick.

Mario said, “I’d like to know this information, not just for my current team members, but for everyone who wants to join my team.”

“I think that’s a good idea,” I said. “You can certainly start to profile anyone applying to your team.”

Step Two: Understand the Role

The second step is to profile the high performers for each different role on your team to figure out their common core attributes. This will reveal what is actually driving performance on the job and provide a success profile for each role.

“I have two different sales roles—a new-business role and an account-management role,” Mario said. “I can see by looking at the top performers for each role that there are some critical differences between the attributes driving success for these two roles.”

“Yes,” I said. “Just like no two individuals have the same profile, no two roles are the same.”

Step Three: Compare Individuals to Roles

The third step is to compare every individual to the roles on your team to figure out who belongs where, who is likely to succeed, and who to invest in.

“I’d like to move to this third step,” Mario said, “by taking a closer look at some of my reps.”