6

The House of Astonishment

It was indeed a house of astonishment. The day before the last day of spring vacation, Mr. Caduggan, who had been having what he called "a jawb" getting the attic door open, finally did get it open and mounted the steep stairs beyond it carefully, testing the treads.

A few minutes after he had reached the top he came licketty-splitting down again, with Popeye at his heels in a three-legged run.

"Mrs. Blake, Mrs. Blake!" shouted Mr. Caduggan. "Oh, Mrs. Bla-ake!"

Portia was startled from her room by his intemperate bellows, and Mr. Caduggan drew up short at sight of her.

"Where's your mama, Portia?"

"In the pantry looking over the china, I think," Portia said. "Why? What is it? What's the matter?"

But Mr. Caduggan was already on his way down the next flight of stairs, with Popeye just behind him, barking impulsively. Portia followed, of course, and Julian joined them in the front hall.

"What goes? Is the house afire?"

"I don't know," Portia said. "I guess not or he'd say so."

They ran after him through the hall, through the dining room, to the pantry. Popeye barked.

Mrs. Blake and Aunt Hilda turned from their work, startled by the racket, and Aunt Hilda nearly dropped a teacup.

"What in the world?" said Mrs. Blake.

"Well, I tell you, ma'am," Mr. Caduggan said gustily, heaving with mystery and importance. "If you'll just step up-attic for a minute, I think there's something there you'll want to see."

Foster and Davey, who had been in the laundry, sitting cozily in a washtub reading comics, dislodged themselves and came to find out what was happening.

"What in the world?" repeated Mrs. Blake, dusting her hands on her dusty apron. "What can it be, Mr. Caduggan?"

"I'd rather you saw for yourself, ma'am," he replied cryptically.

"Is it something good or something bad?" Portia pleaded as they all mounted the stairs to the second floor.

"Wait and see," said Mr. Caduggan.

"Is it something dangerous?" asked Foster, alight with hope.

"Is it a live thing?" asked Davey. And then he asked in a lower tone: "Is it a dead thing?"

"Wait and see," replied Mr. Caduggan imperturbably.

At the attic door he turned and said: "One at a time, please, up these stairs. They ain't none too steady. Need bracin'. Mrs. Blake, you first, ma'am."

Mrs. Blake ran lightly up the wooden steps, then Aunt Hilda, then the children (Julian first, as usual).

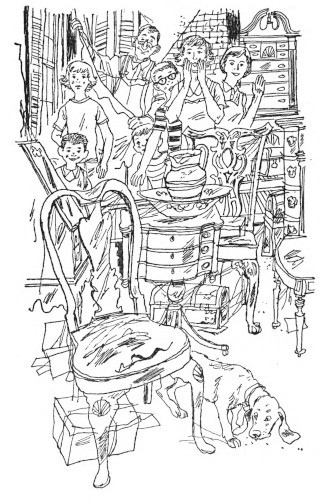

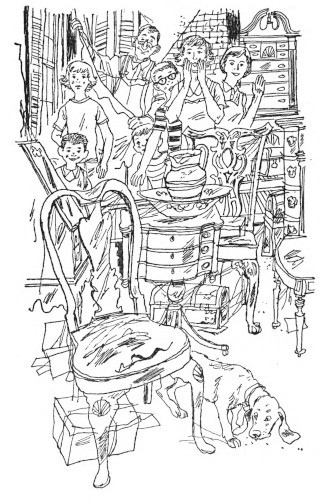

It was dim "up-attic" and like the rest of the house, full of objects and full of dust. Mr. Caduggan went to a window and ripped off the dark and rotting window shade.

"There," said he.

Mrs. Blake drew in her breath. So did Aunt Hilda.

"Duncan Phyfe!" exclaimed Mrs. Blake, in the low voice of awe.

"Duncan who? I don't see anybody," Foster said.

"Chippendale!" exclaimed Aunt Hilda. "Can it really be? But it is, it is! Oh, Barbara, look! Queen Anne!"

Portia and Julian wondered if their mothers had gone mad.

"Are they talking about all those old bureaus and things?" Foster demanded; he could see that they were, and he was disgusted. Downstairs the house was a regular furniture store, it was so full of tables and sofas and chairs and desks; and now here was all this excitement about still more furniture. He could not understand it.

Mr. Caduggan attempted to explain. "Well, see, the furniture up here is real old; what they call antique, see. It's like two hundred years old, give a little take a little, and what's more it was made when folks knew how to make furniture. My dad was a cabinetmaker, and his dad before him. I learned about good furniture from them. Look at this, for instance; this is real fine work: satinwood inlay. My, my, look at that work."

Portia could see that the pieces were beautifully made, beautifully ornamented with carved shapes of shells, urns, even of flames. But Julian inclined toward Foster's view.

"Still it's only furniture," was his judgment. "If it was gold or jewels or Greek statues, or something, I could understand it. But just a lot of old furniture when you've got a lot of old furniture—I don't see why it's so great."

"Look, my young realist," Mrs. Blake said. "Regard it in this light. The tall cabinet over there, with the urn-shaped finials is called a highboy. Aside from its beauty, it is extremely valuable. If I can ever bear to part with it, it will not only pay the bill for all the new copper piping this house must have, it will probably pay for the entire electric system as well. And that is only one among these priceless things...."

"Wow!" Julian conceded.

"And of course I will have to part with some of them," his aunt continued. "As you know, the Blake family is far from rich. What Mr. Caduggan has discovered is not only a treasure-trove; it is a lifesaver!"

The children looked at the furniture with new respect after that, though it was impossible for them to take great interest in it. Enthusiasm concerning furniture is something that belongs to grownups. Mrs. Blake and Aunt Hilda were in a trance of joy, prowling about among the pieces, opening little doors and drawers, exclaiming with wonder and delight. No less engrossed and pleased was Popeye, lured hither and thither by a stimulating age-old smell of mouse. He snuffled, scuffled, whined, and scratched, thoroughly contented.

Foster pushed his way between objects to the dormer window. From this he could look down with a new eye at "The Property"—leafless bushes, ragged loop of drive, brown slopes studded with crocuses. Eli Scaynes rounded the corner trundling a wheelbarrow full of sticks and twigs. He looked very small, and so did Julian's dog, Othello, sniffing about in the orchard. Neither knew that anyone was watching him, and that made each of them look lonesome.

"Come on, Dave; let's go outdoors," said Foster, and the two of them went pounding down the stairs.

"But why do you suppose Mrs. Brace-Gideon kept all those marvels in the attic?" Mrs. Blake wondered.

"Well, judging from the way she furnished her house, these simply weren't to her taste," Aunt Hilda said. "Not fashionable enough, probably."

Besides the furniture, this part of the attic was crowded with a great collection of bedroom crockery, pitchers, basins, bowls of all sizes and shapes; boxes piled on boxes, and trunks on trunks; there was another dressmaker's dummy, rather stouter than Baron Bloodshed; there was an agitated-looking sewing machine, an agitated-looking typewriter, both rusty; and a large, elaborate bird cage that must once have housed a parrot.

"Things and things to look at and discover, all summer long," Portia gloated. "Now where does this door go, I wonder?"

"Well, let's find out."

The door was at the end of the attic storeroom. Julian turned the handle and gave a shove; for a wonder it yielded easily.

Opening off a narrow corridor were six small rooms, three to a side, each with an iron bedstead, a washstand, a small looking glass, and a mousetrap. The little rooms smelled musty and dry, the wallpaper was stained, and fallen plaster lay on the floors. Portia found a broken rosary in one room, and on the wall of another there was a tacked-up faded postal card, showing the picture of a lighthouse. It looked very forlorn.

"I guess this is where she kept her servants," Julian said.

"In these horrid little rooms?" Portia was shocked. "Why, they're like the rooms in a jail!"

But then she remembered the tale of how Mrs. Brace-Gideon had been in the habit of acquiring two kittens for pets each summer, and then when it was time to return to the city, she would take them to the vet's and have them chloroformed (until Baby-Belle Tuckertown had outwitted her).

"I think Mrs. Brace-Gideon was a—was a—what's that word that means you do whatever you want no matter who doesn't want you to?" Portia demanded.

"Ruthless?"

"Yes. I think she must have been a ruthless, ruthless lady!"

"Aunt Minnehaha says she wasn't so bad," Julian said. "Just too rich to understand much. Anyway, lots of people treated their servants that way in those days."

Portia looked at the narrow corridor, at the narrow, neglected rooms. They made her feel dreary, as though other people's dreariness still lingered there.

"Well, I know one thing," she said. "Someday, I'm going to fix these rooms up so they'll look cheerful."

That afternoon Portia and Julian were dispatched to Gone-Away to invite Mrs. Cheever for a cup of tea.

"If anyone knows why those beautiful things are stuck away in the attic, she will," said Mrs. Blake.

And it was true. After they had escorted Mrs. Cheever back and after she had cautiously mounted the attic stairs and done her share of grown-up furniture-worshiping, they all returned to the drawing room for tea poured out of a Thermos bottle, and she told them what she remembered.

"It all comes back to me, now," Mrs. Cheever said, holding her teacup daintily and watching its fragrant steam. "Yes, yes, indeed it does. Mrs. Brace-Gideon had two houses, you know: this one for summertime, and another still grander—oh, very grand, a mansion!—in Pittsburgh. Shortly before she died, she sold the Pittsburgh house with the intention of removing to California for the winters. (That is how she happened to be in San Francisco at the time of the earthquake.) And it seems to me—yes, I do recollect—that she sold the house furnished, except for some very old pieces in the attic. They were not to her taste at all, oh, not at all, but they had been in the family for generations, so out of sentiment she kept them...."

"Thank fortune," said Mrs. Blake.

"Thank fortune," agreed Mrs. Cheever. "Family sentiment, yes, of course, but no doubt her shrewd eye for value played a part, too.... So she stored them here (temporarily, she thought).... Now as I recall, the American pieces, the Duncan Phyfe and so on, had belonged to her grandmother—I think it was her grandmother—but I know that all the rest had been brought in a sailing vessel clear around the Horn by her great-grandfather, a Captain Deuteronomy Dadware. I remember his name because how could one possibly forget it?"

Mrs. Cheever sipped her tea delicately. She was wearing a crimson wool dress, a high lace collar, and many long chains of beads. The bow that always sailed on top of her crimped white hair was the same color as her dress. The walk in the March wind and now the hot tea had caused a wintry pinkness to come into her cheeks. She looked very nice, Portia and Julian thought. They were sitting cross-legged on the floor, drinking their own tea and eating whatever was available.

"Aunt Minnehaha, was Mrs. Brace-Gideon what you would call a ruthless woman?" Portia asked.

"In certain ways she was, yes, indeed she was," replied Mrs. Cheever decisively. "She was very determined. She not only wanted to have her own way; she simply had to have her own way, and because of her strong will and her great wealth she very often got it. Nature, weather particularly, was a severe trial to her because it simply would not comply or submit. When we had bad spells of rain or cold, my father said it must be harder on Mrs. Brace-Gideon than anybody because she couldn't do a thing about it. She couldn't write to the management or to the New York Times. She couldn't fire anybody or bribe anybody. She, with all her money, had to live through bad weather just like the beggar in his hut.

"But," continued Mrs. Cheever, "she was just when she saw that justice was required, and she was very brave.

"One day, one of her maids, Nelly, fell off the end of a Gone-Away dock—I forget how—into deep water. She couldn't swim a stroke and was beginning to gulp and go under, but Mrs. Brace-Gideon stood on the end of the dock and shouted: 'Nelly, I forbid you to drown! I forbid it! You wait right there!'

"And do you know Nelly didn't drown because she didn't dare to; she managed to keep her head above water somehow until Mrs. Brace-Gideon—who couldn't swim a stroke either, mind you!—jumped right into the lake wearing her hat and holding her parasol, in all her heavy clothes and her heavy corsets and her heavy jewelry! It's a wonder she ever came up again, but she did, thank fortune, and clinging to a piling, she reached out her parasol so that Nelly, poor creature, could grasp it and be towed in. Then Mrs. Brace-Gideon, holding on to Nelly with one arm and the piling with the other, began calling for help in the loud, strong operatic voice she had, and everybody heard her and came running. My father said he never forgot Mrs. Brace-Gideon being hoisted out of the lake still wearing her big wide picture hat. In those days, of course, ladies' hats were always skewered on with hatpins."

"I wish I'd seen her," Julian said.

"What other brave things did she do?" Portia wanted to know.

"Well, one night—haven't I told you this? But no, I'm sure I haven't—one night, when she couldn't sleep, she became aware of a sound downstairs, a very small but suspicious sound. It was late—oh, I think two or three o'clock!—so she got up, put on one of the magnificent dressing-gowns she had, and tiptoed out to listen.... Well, sure enough, she heard the sound again, whatever it was like, a sort of careful clinking or chinking, I imagine, and she was convinced it was a robber!

"So she crept down the stairs. Crept! For such a commanding woman, she could be very quiet when she needed to.... A light was coming faintly from the drawing room—this very room (or so she said).... At the foot of the stairs she picked up that cast-iron pug-dog doorstop—you know the one?"

"I do," Julian said feelingly. "I tripped over it and fell down, hard, the first time I ever came exploring in this house!"

"Then you know how solid it is. So Mrs. Brace-Gideon tiptoed to the drawing-room door and peeked in, and there, yes, there was a man—a burglar—kneeling on the floor, with a dark lantern beside him and a pistol in one hand! And the door of the safe was open before him!"

"A safe? You mean it? In this very room?" Julian's eyes were shooting sparks.

"Well, that's what she told us, Julian. But you must remember that Mrs. Brace-Gideon was not what one would call a trusting person; no, she was not. So the safe may very well have been concealed in some other room. However, the rest of the story is absolutely true. Every bit of it."

"So she saw this burglar...." Portia prompted breathlessly.

"So she saw him. She was a large woman, as you know: imposing. And I am sure that outrage must have made her twice as large, twice as imposing!... Well, she stepped quietly up to this creature, this burglar, and she said: 'Halt! I command you to halt!' Oh, she had an imperious voice! It could be terrible when she was giving orders....

"The poor burglar was so startled that he dropped the pistol, and Mrs. Brace-Gideon, with great presence of mind, moved in and put her foot on it firmly, and then she hit him on the head with the cast-iron pug-dog! Well, over he went, just plain keeled over on the floor, entirely unconscious. And while he was unconscious, she went to the windows, ripped off the portiere cords, and bound him up with them, trussed him up tight like a good rolled roast, and when that was done—and the safe closed up again, I'll be bound—she began ringing bells for the servants as hard as she could. The coachman was sent for the constable; the burglar, still unconscious, was carried off to jail; and then, only then, Mrs. Brace-Gideon crossed her ankles gracefully and permitted herself to faint on the divan of the Turkish cozy corner!"

"Goodness!" said Mrs. Blake.

"I'm glad this house isn't haunted," Aunt Hilda declared. "I think Mrs. Brace-Gideon might have made a very dominating ghost."

Julian stood up, putting his cup and saucer on the tray.

"I'm just wondering about that safe, though," he said. "I mean maybe it's still here, somewhere. Would you mind if I sort of investigated, Aunt Barbara?"

"Do! By all means," said Mrs. Blake.

So from that moment, until it was time to escort Mrs. Cheever back to Gone-Away, Portia and Julian prowled and crouched about the room, tapping at the walls and wainscoting, testing the floor boards, feeling around picture frames for concealed catches—"because it just might be behind a picture door, like the sheep-lady door," Julian said.

But their search was to no avail.

"Never mind," said Mrs. Cheever, as they walked back through the windy dusk. "Just as I told you, Mrs. Brace-Gideon was not a trustful person. No, she was not. I am certain she would never have told anybody where the safe truly was; or if she had to tell them truly at the time, she would then have moved it elsewhere. You may still find it, children, but I doubt there'll be a penny in it."

"It's just that it's fun to look," Julian explained. "It's fun to think about."

"Oh, I wish I didn't have to go back to the horrible, loathsome, disgusting old city!" Portia groaned.

"Never mind," Mrs. Cheever said again. "Think of how beautiful it will be when you come back: all the reeds of Gone-Away tipping and swishing, and the redwings calling, and the bullfrogs grumping, and the roses just—Oh, I declare I can hardly wait for it myself! No matter how old a person gets, he's never old in spring!"

Only three of them: Foster and Portia and Mr. Blake took the train from Creston the next morning. Mrs. Blake would have to stay behind for several weeks until the house was in more livable shape.

Portia and Foster would miss their mother, of course, but they knew they wouldn't fare too badly. Mrs. Bryant would clean the house each morning. Mr. Blake knew how to cook steaks, chops, hamburgers, and hot dogs. He could also bake a potato. Portia knew how to cook pancakes and fudge. Foster knew how to make chocolate milk. As for Gulliver, his food came out of a can.

"So we'll be all right, we'll be fine," Mr. Blake assured his wife.

"Of course you will, I know you will," she said. "But, Paul darling, do see that Foster really brushes his teeth, not just strokes them. And do watch him with the catsup. If you let him, he'd pour it on his food the way Vesuvius poured lava on Pompeii. I don't see how he knows what he's eating. And then about Portia—"

But fortunately for Portia, the train arrived at that moment.

From its windows, after only ten days, the country they traveled through already seemed less the property of winter. All the snow patches were gone, and the trees, especially the willows, showed a color of life in their twigs.

"It won't really be very long before we come back," Portia said, to comfort both herself and Foster. "It only seems long."

"That's just the same as being," Foster said.