5

The Sheep-Lady's Secret

The next eight days flew by for the Blake family. Every morning they returned to the Villa Caprice ("I wish I could think of another name for the place!" Mrs. Blake kept saying), and every day they worked like beavers. Nor were they alone. Julian and Aunt Hilda always came with them; Uncle Jake when he could steal the time. Mrs. Cheever lent a willing hand, and so did her brother; and then there were the newcomers, newcomers who soon became friends: Mr. Lance de Lacey, the plumber, and his assistant, Henry Bayles; Mr. Matt Caduggan, the carpenter, and his assistant, Joe Baskerville; Mr. Ormond Horton, the painter; and old Eli Scaynes, who did not care to be called "mister" and who was going to "do something about the grounds."

The children liked Mr. Caduggan the best because he brought his dog to work. It was a large tan animal with one game leg and a bent ear, and its name was Popeye.

"Only dog in the world likes spinach," Mr. Caduggan explained. "That's why we call him Popeye. Used to be his name was Duke, but one day while I was to the phone at dinnertime, he come up to the table while my wife wasn't looking, raised up on his hind legs, and et up all the spinach in the dish. Left the liverwurst that was right there, left the ham baloney. Just et up the spinach. So we call him Popeye."

All the men were nice, however. Mr. de Lacey had a beautiful singing voice and the word "Mother" tattooed on his arm in red and blue ink. Henry Bayles handed out free chewing gum. Joe Baskerville was good at cracking jokes. Mr. Ormond Horton had a cat at home that was going to have kittens, and he promised one to Portia. Eli Scaynes knew the name of every bush, bird, flower, and tree, and was a very practiced talker.

The house that had been locked in silence for so many years rang now with sounds of calling and talking, and occasionally of groaning, as Mr. Blake received the news from Mr. de Lacey that he would "have to have all new copper piping," and from Mr. Caduggan that "the carrying timbers under the main floor is settling so bad they'll all have to be propped up on lolly-columns."

There were all the other busy sounds of banging and thumping and sawing and scraping. The ancient smell of mildew and neglect was replaced by robust smells of soap and polish; later there would be a strong odor of wet paint.

Nearly every day somebody discovered something new and important.

Mrs. Blake discovered a Lowestoft tea set wrapped up in very old newspapers at the back of a cupboard. It was white with a pattern of green ivy leaves.

"Why, I remember hearing about that tea set," Mrs. Cheever told her. "Mrs. Brace-Gideon never cared much for it; she thought it too plain. The one she preferred was a fancy one, all curlicues and gold and roses, but she knew that this one was valuable, so she kept it, thank fortune."

"Thank fortune," echoed Mrs. Blake fervently.

Mr. Blake discovered the cellar. "A full cellar!" he exulted. "Someday we can have a furnace and spend the Christmas holidays here."

"Or just plain live here all the time," said Foster.

Portia discovered a closet full of Mrs. Brace-Gideon's old party dresses: bowed and beaded and bugled and spangled and fringed; draped with festoons of ribbons and lace, and each one weighing pounds. "When Lucy Lapham gets here, we can dress up every day," she said.

Foster discovered the dumb-waiter.

In the pantry, which, planning for the future, he had entered several times already by the small serving window, he had noticed in a casual way that there was a door set into the wall. It was a square door, a cupboard door he supposed, set about three feet above the floor. One day he gave it a whack by accident, and hearing that the whack made an unusually hollow drumlike sound, he decided to open the door. It was hard work to get it open because it was stuck in its frame. (Everything in the house was stuck, being swollen with damp and disuse, and all the Blakes developed good muscles and bad blisters that summer simply from the amount of lifting, yanking, shoving, pushing, and pulling that was required of them.)

Finally, though, Foster managed to wrench the thing open, and looked in at what appeared to be a very small elevator in a shaft.

"Hey, Dave!" yelled Foster. "Come look at this!"

Davey came from the kitchen, where he had been industriously grinding up acorns in the coffee grinder; a fact unknown to Mrs. Blake.

"What is it?" he inquired. "An elevator?"

"Not for people. Maybe for dogs," said Foster, who had never seen a dumb-waiter in his life.

"Maybe for children?" Davey wondered.

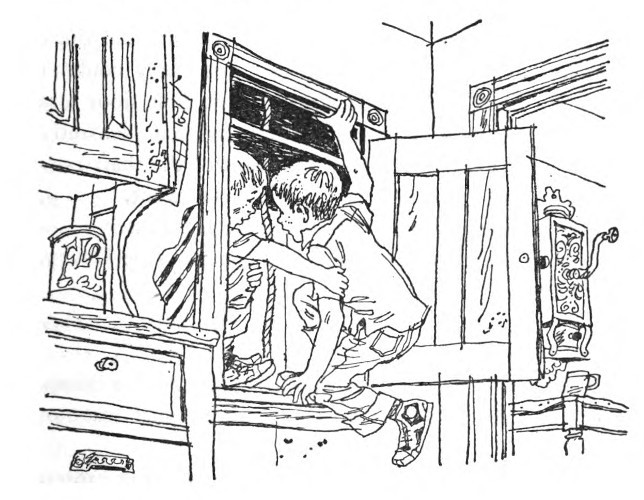

"Well, come on. What are we waiting for?" invited Foster; and he hiked himself up and into the box of the dumb-waiter. "Come on in, Dave; there's room for two if we sit kind of squeezy."

Davey fitted himself in by Foster. It was rich with dust in there, but by now they were very much at home with dust, so who cared. They had to sit cross-legged and pull in their elbows, and if they had been a few years older, they would have had to bend their heads down, too, but as it was they fitted very well.

Foster grasped the prickly hemp rope that hung at one side, gave it a tug, and with a croak and a wobble, their elevator rose up in the shaft.

"Man!" cried Davey in delight. "Give her another yank, Foss, and see if she goes up to the roof!"

It was dark as they went up the shaft, but not badly dark, not pitch dark, because the door below stood open, letting in the light.

Foster maneuvered the dumb-waiter up as far as it would go: to another door on the next story, but there was no latch on the inside, so of course they couldn't open it. Then they went down to the first floor and then up again. The ascending box lurched pleasantly on its rope, knocking against the walls of the shaft now and then and creaking and croaking as it went.

"Up to Pluto, up to the moon!" cried Foster.

"Up to the moon in an old soup spoon!" sang Davey, in a burst of inspiration.

This seemed so terribly funny to them both that they began to giggle.

They reached the top of the shaft again with a bump, and paused there in the exciting darkness that was not dark enough to be scary.

"Up to the moon in an old jelly spoon!" sang Foster, and the giggles redoubled.

At that very instant, outdoors on the front porch, Mr. Caduggan and Joe Baskerville, after a mighty effort and some strong language, managed to force the great front door to open at last. It swung in heavily, rustily, with a slow reluctant groan, and as it gave way, the March wind entered, blew in a current through the hall and the dining room, finally reached the pantry, and firmly slammed the dumb-waiter door.

Total blackness in the shaft.

The giggles stopped abruptly.

"Hey!" yelled Davey.

"Ma-a-a!" yelled Foster. "Daddy!"

They called and called, but no one heard them. After a while, because it seemed the only thing to do, they began to cry.

Portia, coming upstairs to refresh herself with a look at her beloved round room, heard most curious noises: a keening and wailing and then some thumps. But where were they coming from? Where in the world? She listened a moment, then hurried into her parents' room: the big one that had belonged to Mrs. Brace-Gideon herself.

But the room was empty.

Empty of people, that is. Otherwise, it was occupied by large furniture, large mirrors, and on the wall opposite the door a large square oil painting of a motherly-looking barefoot lady wearing a Grecian robe and balancing a sort of pitcher on her shoulder. In the background, above an arrangement of sheep and ruins, fat pink sunset clouds swam in a school.

"Ma-a-a! Boo-hoo!" came the wail, directly it seemed, from the picture itself or from the wall behind it.

Portia felt her scalp creep and, turning, ran from the room, through the hall, and down the stairs, calling in her turn.

"Mother! Daddy! Mother! Daddy!"

Oh, I don't want it to be a ghost, she thought. Oh, I don't want our lovely house to be haunted!

Her mother, holding a ruler and a pair of pliers, emerged from the drawing room. Her father, holding a monkey wrench and a can of machine oil, came bounding up from the cellar stairs.

"What is it, Portia?"

"Upstairs, upstairs—oh, I hope it isn't a ghost—somebody's crying in the wall!"

"What?"

"Listen! Just listen!"

With their faces turned toward the ceiling they listened. Faintly they heard the wailing.

"That's not a ghost; that's Foster!" declared Mrs. Blake, running for the stairs. Her husband and daughter were close behind.

"In your room," Portia directed, and when they entered it, her father and mother were as puzzled as she had been.

"But there's nobody.... Foster!" called Mrs. Blake. "Where are you, darling? Can you hear me?"

"We—we're in here. In the elevator thing," gulped Foster's voice, right behind the sheep-lady's picture.

"Oho!" said Mr. Blake, with the tone of one who is inspired. He leaped across the room to the picture and ran his fingers along the heavy gilt frame. "Fake!" he exclaimed. "I thought so! It's not a picture hanging on a wall; it's a door!"

His searching fingers found the partially concealed latch on the right side of the frame, and after the usual struggle of wrenching and tugging, managed to open the picture door. Foster and Davey, two dirty owls, blinked in the sudden light, tear tracks shining on their cheeks.

"Oh, darling!" cried Mrs. Blake, hugging Foster out of the dumb-waiter; then she reached for Davey and hugged him out, too.

"Great Scott, those ropes are ancient!" said Mr. Blake. "Thank the Lord they didn't fail! Luckily they were closed away from the weather all this time. Otherwise—" But he left the sentence unfinished.

Mrs. Blake was so relieved that she began to scold. "Never again, Foster, do you hear? Never! It was a dreadfully stupid thing to do! Those ropes are more than fifty years old: maybe even sixty or sixty-five! They might very well have broken and then—" But she, too, left the sentence unfinished and gave her son another hug instead.

Foster was so relieved that he began to boast. "It was neat! I yanked that old jalopy up till it hit the top, bang! And then I yanked it down till it hit the bottom, bang! And then I yanked it up again, and I bet that old jalopy never went so fast before. It was neat, wasn't it, Dave?"

"Ye-es," Davey said. "But I guess we better never do it again."

"Nope," said Foster soberly, remembering the pitch-black shaft. "I guess we better never."

"But why in the world do you suppose Mrs. Brace-Gideon had a dumb-waiter landing in her bedroom?" Portia asked. "And why did she hide it with that picture?"

"Mrs. Brace-Gideon was a lady of leisure," her mother said. "She probably took her breakfast in bed. The dumb-waiter would bring her tray up each morning, nice and hot, from the kitchen pantry."

"And the painting, no doubt, was put there to conceal a plain functional door with what she considered to be a thing of beauty," said Mr. Blake, studying the picture.

Portia thought of the dumb-waiter and the sheep-lady, and Baron Bloodshed, and the crystal chandelier, and all the other curious or lovely things they had discovered.

"What a place!" she said thoughtfully. "You know what this house is, Mother? Daddy? It is a house of astonishment!”