4

The Victors

"Well, this is ridiculous; there can't possibly be anybody there," Uncle Jake said, looking both annoyed and sheepish.

"We must be suffering from battle fatigue," Mr. Blake agreed. "Let's solve this thing right now!" And he whipped out a flashlight.

The two men strode purposefully through the doorway. Julian followed, looking rather more tentative than purposeful.

"Oh, Paul, be careful," quavered Mrs. Blake, and Aunt Hilda, who was her sister, quavered: "Jake, don't do anything rash!"

But they had hardly time to say the words before they heard a boom of laughter. Uncle Jake stuck his head out.

"Come in, all of you, and see the watchdog Mrs. Brace-Gideon left to guard the door she couldn't bolt!"

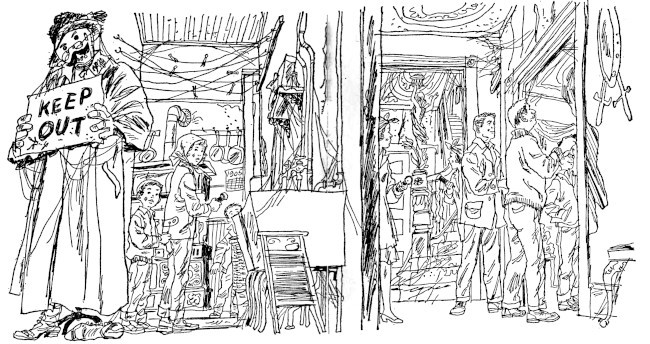

Somehow or other Portia managed to be first, and she couldn't help gasping at the sight before her: the appalling figure dressed in black. It stood there glaring at her, with eyes that had a reddish shine, and in its black-gloved hands it held a placard printed with the words: KEEP OUT!

Of course the thing wasn't real, Portia realized, just some sort of rigged-up trick, but it wasn't very friendly, either, and she was thankful she had not come upon it by herself.

"Heavens, I'm glad I didn't run into this character when I was alone!" her mother said, echoing her thoughts.

On closer inspection the fearsome creature turned out to be built on a dressmaker's dummy.

"Modeled along the noble lines of Mrs. B.-G. herself," Uncle Jake surmised, and gave the thing a friendly spank.

It was dressed in a man's cape-sleeved long black overcoat, riddled with moth holes and furred with dust. Its head was a stuffed stocking top on which a gruesome face had been devised: eyes made of red-glass buttons behind a pair of pinned-on spectacles; a guardsman's mustache cut out of felt; and a dreadful mouth in which white beads were stitched to look like teeth. On its head it wore a Tyrolean fedora tipped a bit to one side. This and the mustache gave it an aristocratic, though shabby, appearance.

"Baron Bloodshed fallen on hard times," Mr. Blake observed.

(Always after that they called the creature Baron Bloodshed, and they were so delighted with him that later, instead of throwing him away, they moth-proofed him and put him in the attic, where he went on scaring people for years, since they kept forgetting he was there.)

"Look, he's even got feet," Foster said; and sure enough, peeping out beneath the long overcoat, there was a pair of dried-up button boots. Foster picked one up to have a look but dropped it when he saw the mouse's nest inside.

"Yikes! I don't think they're living in it, though."

Portia dipped a cautious hand into one of Baron Bloodshed's pockets and was rewarded by finding a small rusted buttonhook. She dipped into another and found an Indian-head penny, dated 1883, which she decided to keep for luck, kindly offering the buttonhook to Foster.

"All right; I don't know what it's for, though," Foster said. "But come on; everybody's gone ahead.”

Training their flashlights forward, they started after the others: through a dark laundry, thronged with tubs and laced with clotheslines overhead; through the dark kitchen with its dimmed old pots and pans hanging from hooks and its big rusted range under an iron canopy. Portia noted the old-fashioned coffee grinder fastened to the wall, the name of the stove, which was "The Marchioness," a tattered calendar for the year 1905. Foster noted a small window into the pantry, just the right size for him to go in and out by quietly and conveniently. Then they pushed open the screechy swinging door and went into the dining room, moving through it rather quickly, for in the darkness it looked gloomy, furnished heavily as it was with carved oak and having walls that were cordially adorned with crossed swords, crossed halberds, crossed battle-axes, and crossed spears. Foster thought that he might enjoy these; but later. Not now.

They followed the sound of voices through the front hall, where on the newel post of the broad stairway a bronze lady four feet tall stood on one tiptoe foot, flourishing a gas lamp over her head. And then they turned left into the large, elaborate room that Mrs. Brace-Gideon had always called her "drawing room."

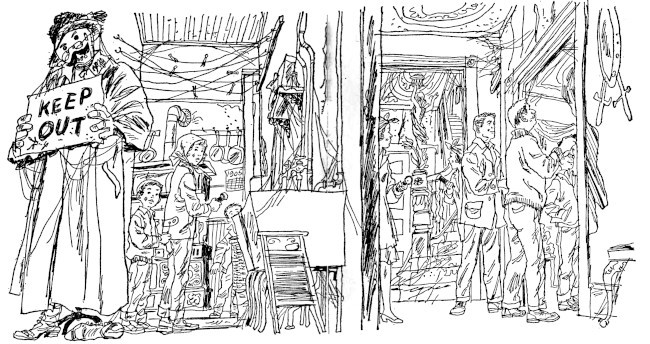

Everyone was there, twinkling about with flashlights.

Portia and Foster had only seen the room once before, and they had forgotten how big it was and how crowded with furniture. There was a huge piano, red and gold, with stout carved ladies holding up the keyboard. Near it stood a shrouded harp, and above that, hanging from the middle of the ceiling, was a great bag like a wasp's nest, and they knew there was a chandelier inside it.

"Paul, let's get some daylight in the place," Uncle Jake said. "Then we'll know what we've got here."

The men went out the way they had come, and presently, after a noise of wrenching and banging, one window opened its eye and the daylight came in; then another and another.

"Good heavens, look at the dust!" said Mrs. Blake.

"Look at the cobwebs," said Foster.

"Look at the mildew," said Aunt Hilda.

"Look at the stuffing coming out of the chairs," said Portia.

"Oh, dear," said Mrs. Blake.

The place really was a spectacle of decay. At one end of the large room a curtain made of bamboo beads hung sadly, many of its strands fallen to the floor in little heaps; and in one corner a deep divan piled with cushions was tented over with a canopy draped on a pair of spears, and simply sagging with a weight of dust.

"A Turkish cozy corner!" Aunt Hilda sighed with pleasure. "Great-Aunt Ida had one exactly like it. I'm sure there's not another left in all the world."

"This one won't be left for very long, either," Mrs. Blake assured her. "Foster, don't sit down on it!"

"Heck, why not?"

"It's probably full of spiders," Portia told him.

"Or maybe rats?" Foster suggested hopefully.

His mother looked far from happy.

Aunt Hilda went over to one of the windows and, after a short struggle, managed to open it wide. The first fresh air in more than fifty years came into the room, chilly, but it brought a smell of spring. Beside the window, heavy curtains of torn damask flapped softly, shaking down more dust.

Julian came into the room carrying a stepladder that he'd found in the laundry.

"What are you going to do, Jule?" asked Portia.

"I want to set the chandelier free," he said, opening the ladder and ascending. "Hold onto it, will you, Porsh? I don't know how strong it is."

Standing on tiptoe, he began to unfasten the dark baize cover of the chandelier; dust smoked up from it; dead moths, dead spiders, dead gnats showered down.

"Ow, watch it, Jule!" protested Portia, spitting out dried moth wings.

"You're all right; you've got your head tied up in a rag. All you have to do is keep your mouth closed, but I can hardly breathe," Julian said, and sneezed six times, as if to prove his point.

"Look out below!" he called in a moment, and Portia skipped aside as the baize bag dropped to the floor in a cloudy heap.

"Wow! Look at that!" shouted Foster. "It's like an upside-down fountain!"

And that was the way the chandelier did look. Elaborate, sparkling, it had been closed away from dust all these years, and its many lusters trembled, fresh and bright as drops of ice water.

"What a lovely thing!" cried Aunt Hilda. "Barbara, do you realize what you have? A Waterford chandelier!"

"Waterford? Really? Yes, I do believe it is!" Mrs. Blake's face, which had been rather worried and upset, began at once to have another look.

Foster jumped up and down as hard as he could to see if he could make the chandelier tinkle, and he did: it even sounded like ice water, or like the pieces of ice in ice water.

"Foster, for pity's sake, stop!" said his mother. "Julian, as long as you've brought the ladder, would you mind taking down those dreary curtains? And now let's start our house cleaning."

Soon they were all at work; even Foster had a cloth, which he flapped and whacked at everything, stirring up much more dust than he disposed of.

"It's fun to sweep and clean when there's plenty of real dirt," Portia said enthusiastically, wielding her broom. "The trouble is there's not usually enough to make anything look any better when you're through."

Outdoors the men still banged and hammered at the window boards, with Davey supervising. Indoors there was a commotion of sweeping and sneezing. The gloomy curtains dropped from their rods, pair by pair, and each time the room grew lighter. Already it seemed a different place.

Somewhere outside a bird began to sing: a real bird, not a sparrow, not a jay; and then, as if the whistling song had been a signal, the sun came out.

"Mrs. Blake, Mrs. Blake!" shouted Davey Gayson, thrusting his head in at the open window. "There's flowers out already, about a hundred of them or a million! I brought you some. Look!" He held out a handful of crocuses: small lighted cups of white and lavender and yellow. "They're all over!" he said triumphantly, feeling as if he had invented them.

Mrs. Blake took the little bunch of flowers. The bird sang. The chandelier chimed softly as air moved in the room, and then the sunlight caught it and all the many lusters blazed and dazzled.

"Oh, I think we're going to love this house," said Mrs. Blake.

"Going to? I love it already," Foster declared.

"So do I, I'm crazy about it," Portia agreed, giving her brother a hug before he could defend himself.

As for Julian, he felt so fine that he went over to the piano and played a chord that sounded like a broken bedspring.

"Perhaps some day we can afford to buy that piano a new set of insides," Mrs. Blake said, dusting off one of the stout gilded ladies that held up the keyboard. "But until then it's just going to stay here as it is; I could never bear to part with it."

"Oh, never!" Aunt Hilda agreed. "Just looking at it makes you think of all those big, fat, glorious singers that Great-Aunt Ida used to talk about: Schumann-Heink and Nordica and Nellie Melba. And of boxes at the opera stuffed with people named Vanderbilt and Astor, all flaming with diamonds and waving fans made of feathers...."

"It doesn't look as if it should make piano noises," Julian said. "I mean it's so fancy and gaudy, it ought to make kind of a loud racket of tunes like a jukebox or a steam calliope."

"Or a fire engine," added Foster, influenced by the combination of red and gold; and having uttered the words, he became a fire engine himself, howling and wailing like a siren and careening busily about the crowded room, taking each corner on two wheels.

"Out, Foster, out! Out!" commanded his mother, flapping her dustcloth at him. "Go find Davey and stay outdoors!"

Willingly the fire engine departed through a window, siren going full blast.

By noon the room was beginning to show signs of being conquered. The moth-eaten rugs had been flung out of the window; so had the curtains, and so had the doleful swags above the Turkish cozy corner.

"But, Mother, please leave the bamboo curtain, will you? Please?" Portia pleaded. "Listen to the sound it makes." She ran her fingers across the strands, which did make a delicious sound: small hailstones rattling on dry leaves.

"Well, I don't know. It is rather pretty. All right, I will," her mother said. "But on one condition, dear: that you will string the beads and put the fallen strands back up again."

Portia agreed willingly to this (and lived to regret it later, for it proved to be a most tedious job and took hours. Still it looked very pretty in the end).

A sound of noon whistles, one from Attica, one from Pork Ferry, came through the open windows, and then a welcome call from the men. They had brought the lunch from the station wagon, and everyone was starved. They all went out by way of the window, and Davey led them to the place where the crocuses, "a hundred of them, or a million," were starred over a gentle slope that once had been a lawn.

"Is the water running in the pipes yet?" Foster wanted to know, and when his father told him it wasn't, he said: "Hooray, then we can't wash, we can't wash, we can't wash!"

"Yippee!" was Davey's comment, but Aunt Hilda said: "Not so fast"; and she produced a gallon Thermos jug. "Hot water for washing hands only; we can't waste it on faces. And here's a bar of soap."

"Heck," said Foster, but he did the job.

Then all of them, with clean hands and dirty faces, settled down to the delightful occupation of eating sandwiches and deviled eggs and fruit and Aunt Hilda's angel cake. The sun was warm on their heads, and the air smelled of spring, and they kept looking up proudly at the queer old towered house that they were bringing back to life again.

All they were able to do that day was to clean the drawing room and the front hall. By the time they were done, the walls had been cleared of hanging wallpaper strips and dusted down; the floors had been swept, scrubbed, and waxed. The divan of the Turkish cozy corner, gingerly dismantled (and proved to be the archaeological site for many civilizations past and present of clothes moths, silver fish, spiders, and beetles), had been thrust out the window, since the front door refused to budge, to join the other discards on the grass.

Mrs. Blake kept wandering about the room and pausing to observe it, first from one angle, then another. She looked very happy and dirty. All of them were dirty, black as sweeps and exhausted, but all felt sustained by the satisfaction of accomplishment.

"Time to call it a day," Mr. Blake said at last, peering in at the window. "We've liberated thirty-seven windows and the back door. And that's enough!"

He also admired the work of those who had stayed indoors, and climbed over the sill to exclaim about the drawing room. So did Uncle Jake.

Portia and Julian were sent in search of the little boys, who were finally located in the greenhouse, resting among ancient flowerpots. They had had an extremely busy afternoon exploring what Foster grandly called "The Property."

"We found a brook way back in the woods," he said. "We own the piece of it that goes through 'The Property,' don't we, Daddy?"

"It's ours to use, at least."

"There's a bridge across it," Davey added. "Kind of a. It's pretty rotten, I guess."

"He fell through," Foster said casually.

"Oh, Davey," cried Mrs. Blake. "Are you soaked? What will your mother say!"

"I dried off all right; it was a good long time ago," Davey assured her. "So she won't care."

"Well, I just hope you don't catch cold!"

All of them, in straggling procession, trailed along the nearly obliterated drive. Mr. Blake had a swollen thumb from banging it with a hammer; Uncle Jake had a crick in his back. Mrs. Blake had a bruise on her shinbone, and Aunt Hilda had one on her elbow. Julian had a cut on his hand, and Portia had a splinter under her fingernail. As for the little boys, their jeans were stuck with last year's burs; old goldenrod fuzz clung to their sweaters; and where the brambles had managed to reach their skin, they were scratched.

"We look more like a left-over army than ever," Mr. Blake observed. "But I'm not quite sure whether we're the victors or the vanquished."

"Why, we're the victors, Daddy. You know that!" Portia chided him.

"I wish all battles were as pleasant," her mother said. Then she said: "I don't think yellow after all. No. Something warmer. Coral or rose; or a rose pattern."

"Linoleum?" Foster asked.

"Curtains," replied his mother.

That night before he went to bed Foster emptied the pockets of his jeans, which, if they had been clean in the morning, now looked very tired and dirty, just the way he liked them.

The pockets yielded a good assortment: a brass ring from a portiere, several flaky pieces of mica, two rather bashed-in oak galls, a pine cone, a bone of unknown origin, an empty milkweed pod, and Baron Bloodshed's buttonhook.

He set the oak galls, the pine cone, and the milkweed pod on his bureau to decorate it, but put everything else back in his pockets. Pockets, after all, are to keep things in.