CHAPTER IV

EFFIE AND BOBBIE

WHEN Maya awoke the next morning in the corolla of a blue canterbury bell, she heard a fine, faint rustling in the air and felt her blossom-bed quiver as from a tiny, furtive tap-tapping. Through the open corolla came a damp whiff of grass and earth, and the air was quite chill. In some apprehension, she took a little pollen from the yellow stamens, scrupulously performed her toilet, then, warily, picking her steps, ventured to the outer edge of the drooping blossom. It was raining! A fine cool rain was coming down with a light plash, covering everything all round with millions of bright silver pearls, which clung to the leaves and flowers, rolled down the green paths of the blades of grass, and refreshed the brown soil.

What a change in the world! It was the first time in the child-bee’s young life that she had seen rain. It filled her with wonder; it delighted her. Yet she was a little troubled. She remembered Cassandra’s warning never to fly abroad in the rain. It must be difficult, she realized, to move your wings when the drops beat them down. And the cold really hurt, and she missed the quiet golden sunshine that gladdened the earth and made it a place free from all care.

It seemed to be very early still. The animal life in the grass was just beginning. From the concealment of her lofty bluebell Maya commanded a splendid view of the social life coming awake beneath. Watching it she forgot, for the moment, her anxiety and mounting homesickness. It was too amusing for anything to be safe in a hiding-place, high up, and look down on the doings of the grass-dwellers below.

Slowly, however, her thoughts went back—back to the home she had left, to the bee-state, and to the protection of its close solidarity. There, on this rainy day, the bees would be sitting together, glad of the day of rest, doing a little construction here and there on the cells, or feeding the larvæ. Yet, on the whole, the hive was very quiet and Sunday-like when it rained. Only, sometimes messengers would fly out to see how the weather was and from what quarter the wind was blowing. The queen would go about her kingdom from story to story, testing things, bestowing a word of praise or blame, laying an egg here and there, and bringing happiness with her royal presence wherever she went. She might pat one of the younger bees on the head to show her approval of what it had already done, or she might ask it about its new experiences. How delighted a bee would be to catch a glance or receive a gracious word from the queen!

Oh, thought Maya, how happy it made you to be able to count yourself one in a community like that, to feel that everybody respected you, and you had the powerful protection of the state. Here, out in the world, lonely and exposed, she ran great risks of her life. She was cold, too. And supposing the rain were to keep up! What would she do, how could she find something to eat? There was scarcely any honey-juice in the canterbury bell, and the pollen would soon give out.

For the first time Maya realized how necessary the sunshine is for a life of vagabondage. Hardly anyone would set out on adventure, she thought, if it weren’t for the sunshine. The very recollection of it was cheering, and she glowed with secret pride that she had had the daring to start life on her own hook. The number of things she had already seen and experienced! More, ever so much more, than the other bees were likely to know in a whole lifetime. Experience was the most precious thing in life, worth any sacrifice, she thought.

A troop of migrating ants were passing by, and singing as they marched through the cool forest of grass. They seemed to be in a hurry. Their crisp morning song, in rhythm with their march, touched the little bee’s heart with melancholy.

Few our days on earth shall be,

Fast the moments flit;

First-class robbers such as we

Do not care a bit!

They were extraordinarily well armed and looked saucy, bold and dangerous.

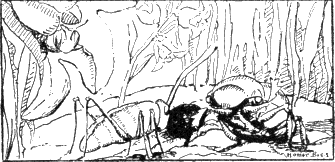

The song died away under the leaves of the coltsfoot. But some mischief seemed to have been done there. A rough, hoarse voice sounded, and the small leaves of a young dandelion were energetically thrust aside. Maya saw a corpulent blue beetle push its way out. It looked like a half-sphere of dark metal, shimmering with lights of blue and green and occasional black. It may have been two or even three times her size. Its hard sheath looked as though nothing could destroy it, and its deep voice positively frightened you.

The song of the soldiers, apparently, had roused him out of sleep. He was cross. His hair was still rumpled, and he rubbed the sleep out of his cunning little blue eyes.

“Make way, I’m coming. Make way.”

He seemed to think that people should step aside at the mere announcement of his approach.

“Thank the Lord I’m not in his way,” thought Maya, feeling very safe in her high, swaying nook of concealment. Nevertheless her heart went pit-a-pat, and she withdrew a little deeper into the flower-bell.

The beetle moved with a clumsy lurch through the wet grass, presenting a not exactly elegant appearance. Directly under Maya’s blossom was a withered leaf. Here he stopped, shoved the leaf aside, and made a step backward. Maya saw a hole in the ground.

“Well,” she thought, all a-gog with curiosity, “the things there are in the world. I never thought of such a thing. Life’s not long enough for all there is to see.”

She kept very quiet. The only sound was the soft pelting of the rain. Then she heard the beetle calling down the hole:

“If you want to go hunting with me, you’ll have to make up your mind to get right up. It’s already bright daylight.” He was feeling so very superior for having waked up first that it was hard for him to be pleasant.

A few moments passed before the answer came. Then Maya heard a thin, chirping voice rise out of the hole.

“For goodness’ sake, do close the door up there. It’s raining in.”

The beetle obeyed. He stood in an expectant attitude, his head cocked a little to one side, and squinted through the crack.

“Please hurry,” he grumbled.

Maya was tense with eagerness to see what sort of a creature would come out of the hole. She crept so far out on the edge of the blossom that a drop of rain fell on her shoulder, and gave her a start. She wiped herself dry.

Below her the withered leaf heaved; a brown insect crept out, slowly. Maya thought it was the queerest specimen she had ever seen. It had a plump body, set on extremely thin, slow-moving legs, and a fearfully thick head, with little upright feelers. It looked flustered.

“Good morning, Effie dear.” The beetle went slim with politeness. He was all politeness, and his body seemed really slim. “How did you sleep? How did you sleep, my precious—my all?”

Effie took his hand rather stonily.

“It can’t be, Bobbie,” she said. “I can’t go with you. We’re creating too much talk.”

Poor Bobbie looked quite alarmed.

“I don’t understand,” he stammered. “I don’t understand.—Is our new-found happiness to be wrecked by such nonsense? Effie, think—think the thing over. What do you care what people say? You have your hole, you can creep into it whenever you like, and if you go down far enough, you won’t hear a syllable.”

Effie smiled a sad, superior smile.

“Bobbie, you don’t understand. I have my own views in the matter.—Besides, there’s something else. You have been exceedingly indelicate. You took advantage of my ignorance. You let me think you were a rose-beetle and yesterday the snail told me you are a tumble-bug. A considerable difference! He saw you engaged in—well, doing something I don’t care to mention. I’m sure you will now admit that I must take back my word.”

Bobbie was stunned. When he recovered from the shock he burst out angrily:

“No, I don’t understand. I can’t understand. I want to be loved for myself, and not for my business.”

“If only it weren’t dung,” said Effie offishly, “anything but dung, I shouldn’t be so particular.—And please remember, I’m a young widow who lost her husband only three days ago under the most tragic circumstances—he was gobbled up by the shrewmouse—and it isn’t proper for me to be gadding about. A young widow should lead a life of complete retirement. So—good-by.”

Pop into her hole went Effie, as though a puff of wind had blown her away. Maya would never have thought it possible that anyone could dive into the ground as fast as that.

Effie was gone, and Bobbie stared in blank bewilderment down the empty dark opening, looking so utterly stupid that Maya had to laugh.

Finally he roused, and shook his small round head in angry distress. His feelers drooped dismally like two rain-soaked fans.

“People now-a-days no longer appreciate fineness of character and respectability,” he sighed. “Effie is heartless. I didn’t dare admit it to myself, but she is, she’s absolutely heartless. But even if she hasn’t got the right feelings, she ought to have the good sense to be my wife.”

Maya saw the tears come to his eyes, and her heart was seized with pity.

But the next instant Bobbie stirred. He wiped the tears away and crept cautiously behind a small mound of earth, which his friend had probably shoveled out of her dwelling. A little flesh-colored earthworm was coming along through the grass. It had the queerest way of propelling itself, by first making itself long and thin, then short and thick. Its cylinder of a body consisted of nothing but delicate rings that pushed and groped forward noiselessly.

Suddenly, startling Maya, Bobbie made one step out of his hiding-place, caught hold of the worm, bit it in two, and began calmly to eat the one half, heedless of its desperate wriggling or the wriggling of the other half in the grass. It was a tiny little worm.

“Patience,” said Bobbie, “it will soon be over.”

But while he chewed, his thoughts seemed to revert to Effie, his Effie, whom he had lost forever and aye, and great tears rolled down his cheeks.

Maya pitied him from the bottom of her heart.

“Dear me,” she thought, “there certainly is a lot of sadness in the world.”

At that moment she saw the half of the worm which Bobbie had set aside, making a hasty departure.

“Did you ever see the like!” she cried, surprised into such a loud tone that Bobbie looked around wondering where the sound had come from.

“Make way!” he called.

“But I’m not in your way,” said Maya.

“Where are you then? You must be somewhere.”

“Up here. Up above you. In the bluebell.”

“I believe you, but I’m no grasshopper. I can’t turn my head up far enough to see you. Why did you scream?”

“The half of the worm is running away.”

“Yes,” said Bobbie, looking after the retreating fraction, “the creatures are very lively.—I’ve lost my appetite.” With that he threw away the remnant which he was still holding in his hand, and this worm portion also retreated, in the other direction.

Maya was completely puzzled. But Bobbie seemed to be familiar with this peculiarity of worms.

“Don’t suppose that I always eat worms,” he remarked. “You see, you don’t find roses everywhere.”

“Tell the little one at least which way its other half ran,” cried Maya in great excitement.

Bobbie shook his head gravely.

“Those whom fate has rent asunder, let no man join together again,” he observed.—“Who are you?”

“Maya, of the nation of bees.”

“I’m glad to hear it. I have nothing against the bees.—Why are you sitting about? Bees don’t usually sit about. Have you been sitting there long?”

“I slept here.”

“Indeed!” There was a note of suspicion in Bobbie’s voice. “I hope you slept well, very well. Did you just wake up?”

“Yes,” said Maya, who had shrewdly guessed that Bobbie would not like her having overheard his conversation with Effie, the cricket, and did not want to hurt his feelings again.

Bobbie ran hither and thither trying to look up and see Maya.

“Wait,” he said. “If I raise myself on my hind legs and lean against that blade of grass I’ll be able to see you, and you’ll be able to look into my eyes. You want to, don’t you?”

“Why, I do indeed. I’d like to very much.”

Bobbie found a suitable prop, the stem of a buttercup. The flower tipped a little to one side so that Maya could see him perfectly as he raised himself on his hind legs and looked up at her. She thought he had a nice, dear, friendly face—but not so very young any more and cheeks rather too plump. He bowed, setting the buttercup a-rocking, and introduced himself:

“Bobbie, of the family of rose-beetles.”

Maya had to laugh to herself. She knew very well he was not a rose-beetle; he was a dung-beetle. But she passed the matter over in silence, not caring to mortify him.

“Don’t you mind the rain?” she asked.

“Oh, no. I’m accustomed to the rain—from the roses, you know. It’s usually raining there.”

Maya thought to herself:

“After all I must punish him a little for his brazen lies. He’s so frightfully vain.”

“Bobbie,” she said with a sly smile, “what sort of a hole is that one there, under the leaf?”

Bobbie started.

“A hole? A hole, did you say? There are very many holes round here. It’s probably just an ordinary hole. You have no idea how many holes there are in the ground.”

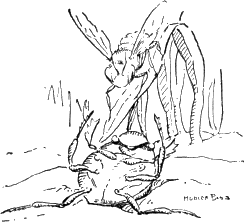

Bobbie had hardly uttered the last word when something dreadful happened. In his eagerness to appear indifferent he had lost his balance and toppled over. Maya heard a despairing shriek, and the next instant saw the beetle lying flat on his back in the grass, his arms and legs waving pitifully in the air.

“I’m done for,” he wailed, “I’m done for. I can’t get back on my feet again. I’ll never be able to get back on my feet again. I’ll die. I’ll die in this position. Have you ever heard of a worse fate!”

He carried on so that he did not hear Maya trying to comfort him. And he kept making efforts to touch the ground with his feet. But each time he’d painfully get hold of a bit of earth, it would give way, and he’d fall over again on his high half-sphere of a back. The case looked really desperate, and Maya was honestly concerned; he was already quite pale in the face and his cries were heart-rending.

“I can’t stand it, I can’t stand this position,” he yelled. “At least turn your head away. Don’t torture a dying man with your inquisitive stares.—If only I could reach a blade of grass, or the stem of the buttercup. You can’t hold on to the air. Nobody can do that. Nobody can hold on to the air.”

Maya’s heart was quivering with pity.

“Wait,” she cried, “I’ll try to turn you over. If I try very hard I am bound to succeed. But Bobbie, Bobbie, dear man, don’t yell like that. Listen to me. If I bend a blade of grass over and reach the tip of it to you, will you be able to use it and save yourself?”

Bobbie had no ears for her suggestion. Frightened out of his senses, he did nothing but kick and scream.

So little Maya, in spite of the rain, flew out of her cover over to a slim green blade of grass beside Bobbie, and clung to it near the tip. It bent under her weight and sank directly above Bobbie’s wriggling limbs. Maya gave a little cry of delight.

“Catch hold of it,” she called.

Bobbie felt something tickle his face and quickly grabbed at it, first with one hand, then with the other, and finally with his legs, which had splendid sharp claws, two each. Bit by bit he drew himself along the blade until he reached the base, where it was thicker and stronger, and he was able to turn himself over on it.

He heaved a tremendous sigh of relief.

“Good God!” he exclaimed. “That was awful. But for my presence of mind I should have fallen a victim to your talkativeness.”

“Are you feeling better?” asked Maya.

Bobbie clutched his forehead.

“Thanks, thanks. When this dizziness passes, I’ll tell you all about it.”

But Maya never got the answer to her question. A field-sparrow came hopping through the grass in search of insects, and the little bee pressed herself close to the ground and kept very quiet until the bird had gone. When she looked around for Bobbie he had disappeared. So she too made off; for the rain had stopped and the day was clear and warm.