CHAPTER V

THE ACROBAT

OH, what a day!

The dew had fallen early in the morning, and when the sun rose and cast its slanting beams across the forest of grass, there was such a sparkling and glistening and gleaming that you didn’t know what to say or do for sheer ecstasy, it was so beautiful, so beautiful!

The moment Maya awoke, glad sounds greeted her from all round. Some came out of the trees, from the throats of the birds, the dreaded creatures who could yet produce such exquisite song; other happy calls came out of the air, from flying insects, or out of the grass and the bushes, from bugs and flies, big ones and little ones.

Maya had made it very comfortable for herself in a hole in a tree. It was safe and dry, and stayed warm the greater part of the night because the sun shone on the entrance all day long. Once, early in the morning, she had heard a woodpecker rat-a-tat-tatting on the bark of the trunk, and had lost no time getting away. The drumming of a woodpecker is as terrifying to a little insect in the bark of a tree as the breaking open of our shutters by a burglar would be to us. But at night she was safe in her lofty nook. At night no creatures came prying.

She had sealed up part of the entrance with wax, leaving just space enough to slip in and out; and in a cranny in the back of the hole, where it was dark and cool, she had stored a little honey against rainy days.

This morning she swung herself out into the sunshine with a cry of delight, all anticipation as to what the fresh, lovely day might bring. She sailed straight through the golden air, looking like a brisk dot driven by the wind.

“I am going to meet a human being to-day,” she cried. “I feel sure I am. On days like this human beings must certainly be out in the open air enjoying nature.”

Never had she met so many insects. There was a coming and going and all sorts of doings; the air was alive with a humming and a laughing and glad little cries. You had to join in, you just had to join in.

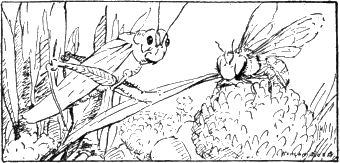

After a while Maya let herself down into a forest of grass, where all sorts of plants and flowers were growing. The highest were the white tufts of yarrow and butterfly-weed—the flaming milkweed that drew you like a magnet. She took a sip of nectar from some clover and was about to fly off again when she saw a perfect droll of a beast perched on a blade of grass curving above her flower. She was thoroughly scared—he was such a lean green monster—but then her interest was tremendously aroused, and she remained sitting still, as though rooted to the spot, and stared straight at him.

At first glance you’d have thought he had horns. Looking closer you saw it was his oddly protuberant forehead that gave this impression. Two long, long feelers fine as the finest thread grew out of his brows, and his body was the slimmest imaginable, and green all over, even to his eyes. He had dainty forelegs and thin, inconspicuous wings that couldn’t be very practical, Maya thought. Oddest of all were his great hindlegs, which stuck up over his body like two jointed stilts. His sly, saucy expression was contradicted by the look of astonishment in his eyes, and you couldn’t say there was any meanness in his eyes either. No, rather a lot of good humor.

“Well, mademoiselle,” he said to Maya, evidently annoyed by her surprised expression, “never seen a grasshopper before? Or are you laying eggs?”

“The idea!” cried Maya in shocked accents. “It wouldn’t occur to me. Even if I could, I wouldn’t. It would be usurping the sacred duties of our queen. I wouldn’t do such a foolish thing.”

The grasshopper ducked his head and made such a funny face that Maya had to laugh out loud in spite of her chagrin.

“Mademoiselle,” he began, then had to laugh himself, and said: “You’re a case! You’re a case!”

The fellow’s behavior made Maya impatient.

“Why do you laugh?” she asked in a not altogether friendly tone. “You can’t be serious expecting me to lay eggs, especially out here on the grass.”

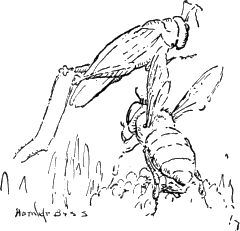

There was a snap. “Hoppety-hop,” said the grasshopper, and was gone.

Maya was utterly non-plussed. Without the help of his wings he had swung himself up in the air in a tremendous curve. Foolhardiness bordering on madness, she thought.

But there he was again. From where, she couldn’t tell, but there he was, beside her, on a leaf of her clover.

He looked her up and down, all round, before and behind.

“No,” he said then, pertly, “you certainly can’t lay eggs. You’re not equipped for it. You haven’t got a borer.”

“What—borer?” Maya covered herself with her wings and turned so that the stranger could see nothing but her face.

“Borer, that’s what I said.—Don’t fall off your base, mademoiselle.—You’re a wasp, aren’t you?”

To be called a wasp! Nothing worse could happen to little Maya.

“I never!” she cried.

“Hoppety-hop,” answered he, and was off again.

“The fellow makes me nervous,” she thought, and decided to fly away. She couldn’t remember ever having been so insulted in her life. What a disgrace to be mistaken for a wasp, one of those useless wasps, those tramps, those common thieves! It really was infuriating.

But there he was again!

“Mademoiselle,” he called and turned round part way, so that his long hindlegs looked like the hands of a clock standing at five minutes before half-past seven, “mademoiselle, you must excuse me for interrupting our conversation now and then. But suddenly I’m seized. I must hop. I can’t help it, I must hop, no matter where. Can’t you hop, too?”

He smiled a smile that drew his mouth from ear to ear. Maya couldn’t keep from laughing.

“Can you?” said the grasshopper, and nodded encouragingly.

“Who are you?” asked Maya. “You’re terribly exciting.”

“Why, everybody knows who I am,” said the green oddity, and grinned almost beyond the limits of his jaws.

Maya never could make out whether he spoke in fun or in earnest.

“I’m a stranger in these parts,” she replied pleasantly, “else I’m sure I’d know you.—But please note that I belong to the family of bees, and am positively not a wasp.”

“My goodness,” said the grasshopper, “one and the same thing.”

Maya couldn’t utter a sound, she was so excited.

“You’re uneducated,” she burst out at length. “Take a good look at a wasp once.”

“Why should I?” answered the green one. “What good would it do if I observed differences that exist only in people’s imagination? You, a bee, fly round in the air, sting everything you come across, and can’t hop. Exactly the same with a wasp. So where’s the difference? Hoppety-hop!” And he was gone.

“But now I am going to fly away,” thought Maya.

There he was again.

“Mademoiselle,” he called, “there’s going to be a hopping-match to-morrow. It will be held in the Reverend Sinpeck’s garden. Would you care to have a complimentary ticket and watch the games? My old woman has two left over. She’ll trade you one for a compliment. I expect to break the record.”

“I’m not interested in hopping acrobatics,” said Maya in some disgust. “A person who flies has higher interests.”

The grasshopper grinned a grin you could almost hear.

“Don’t think too highly of yourself, my dear young lady. Most creatures in this world can fly, but only a very, very few can hop. You don’t understand other people’s interests. You have no vision. Even human beings would like a high elegant hop. The other day I saw the Reverend Sinpeck hop a yard up into the air to impress a little snake that slid across his road. His contempt for anything that couldn’t hop was so great that he threw away his pipe. And reverends, you know, cannot live without their pipes. I have known grasshoppers—members of my own family—who could hop to a height three hundred times their length. Now you’re impressed. You haven’t a word to say. And you’re inwardly regretting the remarks you made and the remarks you intended to make. Three hundred times their own length! Just imagine. Even the elephant, the largest animal in the world, can’t hop as high as that. Well? You’re not saying anything. Didn’t I tell you you wouldn’t have anything to say?”

“But how can I say anything if you don’t give me a chance?”

“All right, then, talk,” said the grasshopper pleasantly. “Hoppety-hop.” He was gone.

Maya had to laugh in spite of her irritation.

The fellow had certainly furnished her with a strange experience. Buffoon though he was, still she had to admire his wide information and worldly wisdom; and though she could not agree with his views of hopping, she was amazed by all the new things he had taught her in their brief conversation. If he had been more reliable she would have been only too glad to ask him questions about a number of different things. It occurred to her that often people who are least equipped to profit by experiences are the very ones who have them.

He knew the names of human beings. Did he, then, understand their language? If he came back, she’d ask him. And she’d also ask him what he thought of trying to go near a human being or of entering a human being’s house.

“Mademoiselle!” A blade of grass beside Maya was set swaying.

“Goodness gracious! Where do you keep coming from?”

“The surroundings.”

“But do tell, do you hop out into the world just so, without knowing where you mean to land?”

“Of course. Why not? Can you read the future? No one can. Only the tree-toad, but he never tells.”

“The things you know! Wonderful, simply wonderful!—Do you understand the language of human beings?”

“That’s a difficult question to answer, mademoiselle, because it hasn’t been proved as yet whether human beings have a language. Sometimes they utter sounds by which they seem to reach an understanding with each other—but such awful sounds! So unmelodious! Like nothing else in nature that I know of. However, there’s one thing you must allow them: they do seem to try to make their voices pleasanter. Once I saw two boys take a blade of grass between their thumbs and blow on it. The result was a whistle which may be compared with the chirping of a cricket, though far inferior in quality of tone, far inferior. However, human beings make an honest effort.—Is there anything else you’d like to ask? I know a thing or two.”

He grinned his almost-audible grin.

But the next time he hopped off, Maya waited for him in vain. She looked about in the grass and the flowers; he was nowhere to be seen.