CHAPTER XXXIII

THE HIGH MOMENT OF THEIR LIVES

WAYNE dined at the Club with Walsh the next evening and told him of the break with his father. Walsh listened in frowning silence to the end.

“It’s a mistake; it’s a great mistake. I’m sorry it’s happened.”

“There was no other way; it had to come. He had no right to jump me because he’s in trouble. I’m not responsible for all his mistakes; I’m one of them myself and it’s enough. He’s hot because he let go of the mercantile company; he has to find some excuse now for doing it and he says you tricked him into selling. The money you paid him went into the hole without making any impression on it.”

“I paid him a fair price and he knows it. The figures were all checked by the audit company. But you had no business breaking with him. I don’t like it. He means to be square; he’s taken his business too easy and now that some of these fancy schemes he’s in have gone bad and the banks are worrying him you oughtn’t to have allowed him to get hot. You oughtn’t to have done it, boy. And, besides, you might have helped him. You must be good for nigh on to eight hundred thousand dollars—all good stuff. It’s all clean. You don’t owe anything, do you?”

“No; nothing worth mentioning.”

“You ought to help him. It would be the fine thing to do. He’s your father—you can’t get away from that.”

But Wayne was not in a mood for magnanimity. Walsh dwelt at length on his duty, on what was, in the old fellow’s phrase, “the right thing.” He indicated concrete instances of what might be done to help Colonel Craighill back to a firm footing. Certain things should be dropped as worthless encumbrances; the real estate ventures would work out in time; various stocks now pledged as collateral should be redeemed. The pledging of half of Wayne’s estate would strengthen his father immensely with the creditors and might save him from ruin. Wayne listened attentively to Walsh; he saw that it might be done, but he felt no impulse to act on Walsh’s suggestions: he was Roger Craighill’s son no longer.

“Sorry I can’t see it your way, Tom, but I have my side of the case, too. That row yesterday proves how far apart father and I have been. If our relations had been right and what they ought to be he would have asked me for help, or I would have gone to him. But he’s always taken that high and mighty way about things, treating me as though I were a fool, incapable of understanding. He doesn’t really appreciate the serious trouble he’s in. He hardly admits that it’s a temporary embarrassment; you know his way. No, Tom, I don’t feel called on to do the dutiful-son act and dump down on his desk the good assets I inherited from my grandfather and have added to a little bit on my own account. I don’t owe father anything—not even money. I’ve ordered my cars sent to a public garage; I’m going up now to pack my things.”

“The house is all clear; that’s yours.”

“Yes,” replied Wayne with sudden asperity; “it’s my own house I’m leaving.”

“Um. I hope these troubles of the Colonel’s won’t be hard on the little woman up there.”

He spoke half to himself, and when Wayne asked what he had said, Walsh grunted “Um” and rose from the table.

Wayne found a letter in the club office. It was from Jean, written in New York. A large, plain sheet of paper with the writing confined to a square in the centre; the handwriting small, even, distinctive. It was the first message he had ever received from her and he carried it to a quiet corner of the lounging room to read.

“My grandfather is again in Pittsburg. He persists in pressing his claim against your father, though I have begged him to drop it. I am sorry to trouble you about such a matter, but if you can see him I wish you would try to persuade him to go home. He has brooded over his claim until he is no longer himself, and he insisted on staying there at the boarding house when I left.

“The Richardsons have been kind to me in every way. I am at their house and shall be here all the time I spend in New York. I go to my work over on the East Side every day, and the settlement house people look out for me and help me find the models I need.

“I hope you are well and that the new work with Mr. Walsh will prosper.”

Many readings could not torture into this unexpected message any personal interest in himself. This was one reflection, but it was something that she had thought of him in her perplexity. Her shabby old grandfather, with his long-neglected claim, was an unfortunate encumbrance; it was too bad the girl had to be bothered with him. It flashed upon him that he might go to New York and see her, but he dismissed the idea at once. It would only distress her, and he was Wayne Craighill, and to call on Jean at the Richardsons might injure her—a bitter reflection, but one he met squarely. In the end, after he had studied it in all possible angles, he felt happier for this contact with something that had touched her hand. It was almost like her own presence, this sheet of paper with its simple, straightforward message, and the block of script that showed the artist’s “touch.” He would find the bothersome grandfather to-morrow and settle the old claim out of his own pocket and send him back to Denbeigh.

Wayne ordered a motor from a public garage, and rode to his father’s house. It had been his intention to get his things together and leave without seeing his father again. The lower floor was deserted and he kept on to his own room. The remodelling of the house shortly before his mother’s death had made no change in the rooms that had been set apart to him in his youth. There were things there—pieces of furniture that had been in his grandfather Wayne’s house, a number of old engravings and some books, that he could send for later. He packed his trunk as for a journey; making a pile of the excess clothing to be called for later by the club valet. Then he filled a suit case and portmanteau and rang for the house man to carry them down. As he stood at the door taking a last look at the walls that had known him so long, the little travelling clock on the mantel, which had timed him during his years at St. John’s and at the “Tech,” tinkled nine, and on the hint, he picked it up and reopened the portmanteau to make room for it.

The clock on the stair was still chiming as he closed the door. He was rather sorry now that he had not made an effort to say good-bye to Mrs. Craighill—poor Addie; this was, in all the circumstances, almost desertion, this leaving her to fight her troubles alone. To his surprise her sitting room door was open and she stood just outside it, leaning over the stair rail, as though intent upon something below. She raised her hand warningly.

“What’s the matter, Addie?”

“There’s someone in the library with your father. I heard you when you came, and then a moment later this card was brought up. Your father was in my sitting room talking and he seemed very angry at being interrupted—it was a matter of business, he said, and the man had no right to follow him home.”

Wayne took the card which she had in her hand; it bore the name of Andrew Gregory written in pencil. The old claimant, denied access to Colonel Craighill at his office, and smarting under his wrongs, had sought audience here.

“I have heard angry voices once or twice. You had better see what’s the matter.”

She stole downstairs after him. The portières in the library doors were drawn, but voices could be heard quite distinctly, and Wayne recognized the shrill pipe of Gregory raised in angry denunciation; Mrs. Craighill was greatly perturbed and clung to Wayne’s arm as the angry debate continued. The discussion seemed to be approaching an acute phase, and Wayne strode toward the door. Gregory had not been treated right; Wayne had felt that from the beginning, and for Jean’s sake he had meant to effect some adjustment with the old man; but Gregory’s presence in the house created a new situation. Jean’s letter was in his pocket, asking him to see that no harm came to her grandfather. It was his first commission from her hand and the thought of this sent him on to the door. Gregory was not sparing of vituperation; he heaped harsh Saxon epithets upon Colonel Craighill, who roared back at him angrily.

“Get out of my house! You had no right to come here with your preposterous claim; I told you my lawyer would attend to you!”

“You didn’t send me to your lawyer when you wanted my property, you lying hypocrite. And I’m going to publish you to the world now for what you are. There’s no bigger scoundrel in the State of Pennsylvania than you; but now——”

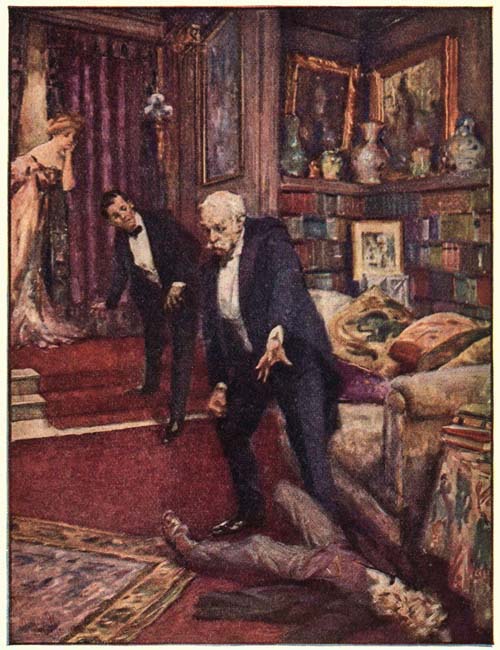

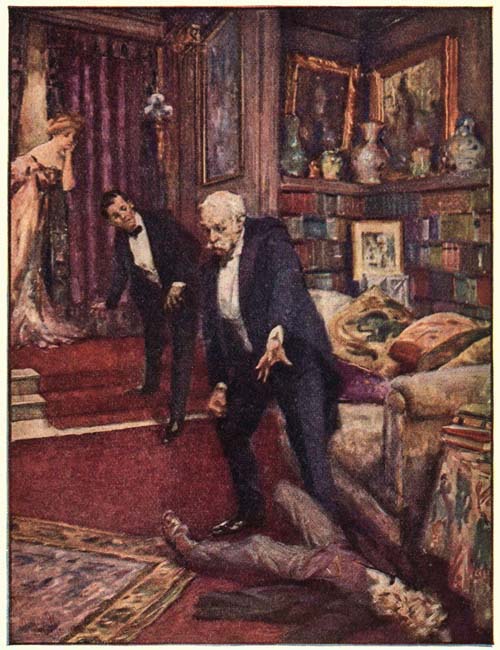

There was a dull sound as of a blow struck and a heavy fall as Wayne flung back the curtains. Colonel Craighill stood there, gazing down at old man Gregory, who lay upon his side, very still. Colonel Craighill’s arm was extended, his body pitched slightly forward, as though palsied at the moment the blow had been struck. He turned a white face toward Wayne, who sprang into the room, with Mrs. Craighill close behind.

Wayne straightened the crumpled figure on the floor and Mrs. Craighill brought water and brandy from the dining room. The two bent over the fallen man, whose breath came in hard gasps. His eyes opened and shut several times and he tried to speak; then his muscles relaxed and he lay still. The marks of death were on him. Wayne and Mrs. Craighill exchanged a glance. She was perfectly cool and said calmly:

“It looks bad. Shall I call a doctor?”

“Wait a moment.”

“THERE WAS A DULL SOUND AS OF A BLOW STRUCK”

Wayne turned to his father, who had sunk into a chair and was cowering there, his eyes staring at the silent, inert figure stretched out on the floor. He knelt and put his head to Gregory’s breast.

“He’s dead, father,” said Wayne quietly.

“Oh, God! he can’t be dead! My blow could never have killed him!”

“There’s no pulse—it’s all over. We’d better think about this pretty hard for a minute. It will be too late when the doctor comes and the servants find out. We must know what story you want told about it.”

Mrs. Craighill still crouched by the old man, and she put her hand to his heart now and satisfied herself that it had ceased to beat. She remained where she was, while Wayne stepped to the doorway and flung the curtains together.

“You struck him, and he is dead; what are we to do about it?” he demanded of his father.

“Why, it isn’t possible, Wayne!” cried Colonel Craighill. “It was more in the way of pushing him from the room than a blow; it may have been on the breast—perhaps over his heart; I can’t remember, but it couldn’t have killed him—it’s a faint—he will come around again all right. Try the brandy, Addie. If we call a doctor——”

He was pitiful in his agitation and kept twitching at his collar and wringing his hands.

“The man is dead,” said Mrs. Craighill. “We must have the doctor; but Wayne is right: before he comes you must know what you are going to say to him; the matter will be reported; we must know what to say.”

“It was heart disease; the blow could never have killed him,” muttered Colonel Craighill.

Wayne knelt again by the quiet figure and laid his ear to the pulseless heart. Mrs. Craighill watched him as he rose, waiting for him to tell her to call the doctor. It was the high moment in all their lives, as she fully realized.

“The situation is just this, father,” and Wayne’s calmness seemed to reassure Colonel Craighill.

“Yes, yes!” he faltered.

“A man has died here in your house. You admit you struck him; and no matter whether death resulted from excitement or from your blow, the thing is ugly. A doctor must be called. Addie, go and telephone for Dr. Silvan, for Gardner, too, and for Wynn—try their houses. Silvan is nearest; call him last. There’s no time for quibbling—what are we going to tell them when they come, and the coroner and the police? It’s for you to say.”

“Oh, my God, Wayne, what am I to do? I tell you I didn’t kill him; I couldn’t have killed him, it was more—why Wayne, you know——”

“The man’s dead, in your house, and you confess that you struck him. What are we going to say about it?”

Mrs. Craighill could be heard in the telephone room calling the doctors. Colonel Craighill paced the floor nervously. He whirled round, his face twitching with excitement, and caught Wayne by the shoulder.

“If we could ignore the blow—if we could say—the man—died—dropped dead—that would be true—quite the truth.”

“But you told me you struck him.”

“Yes, yes; but it was the slightest touch of the hand—it was more in the way of pushing him from the room—you could hardly say I struck him—you could hardly call it an assault, could you, Wayne?”

It was the plea of a man begging for mercy; but contempt and scorn were gathering might in Wayne’s heart. Mrs. Craighill was calling the third doctor, who lived nearest, and the time was short.

“You are Roger Craighill. What you say of this matter will be believed. But when the doctors ask how it happened, wouldn’t it be as well to remember that I was in the house—and that I have no reputation to lose?”

The peace of the dead man at their feet hung upon the room. Colonel Craighill lifted his head, but he did not face his son.

“I don’t understand you,” he gasped.

“Yes,” said Wayne, “I think you do understand,” and he spoke the words slowly, with a sharp precision, but he smiled slightly. He forgot himself, his own life and its better aims; the new aspirations that had visited him during his long self-communing in the hills; the thought of his own honour; the precious faith in life and love that Jean Morley had roused, in him—all went down before this undreamed of, this exquisite vengeance. He had offered to assume responsibility for the death of this old man who lay stiffening there on the floor, and Roger Craighill—his father—would suffer it, would accept the sacrifice and connive at its fulfilment!

Wayne’s eyes were not good to see as he watched his father for some sign. A long silence followed in which neither moved, and when Colonel Craighill turned toward his son it was with a guarded, furtive glance, as though he had hoped to find him gone.

“The doctors are on the way, all of them,” said Mrs. Craighill at the door. “What else is there to do?”

“Nothing,” said Wayne, “but this: when they come, if there’s any question of a blow having been struck, I did it—I did it. And,” he deliberated, “you’d better call Tom Walsh at the Allequippa Club and tell him to come up. He’s a good hand with the newspapers and the police. Good night.”

Wayne rode back to the city in the motor that had carried him home, and at the garage Joe, gossiping with the loafing chauffeurs, heard him order out his racing machine.

They had not met since Wayne’s long absence in the hills, but Joe had learned from Paddock that Wayne was in a place of safety. Wayne’s appearance at the garage and demand for the racer brought Joe up standing, and he took charge of the machine without a word.

Wayne hardly noticed him, so deep was his preoccupation; and this in itself seemed ominous to Joe.

“So you’re going are you, Joe? Well, we’re likely to be gone a long time,” Wayne said, throwing his bags into the car. At the Allequippa Club he cashed a check for a thousand dollars and supplied himself with cigars.

And so they plunged into the night, over the rough roads of spring.