CHAPTER XXXIV

THE HEART OF THE BUGLE

THEY came to Harrisburg, with the sun low in the west and a soft haze enfolding the capitol dome—that proud assertion of a commonwealth’s strength and power that greets the eye of western pilgrims bound for Washington, and speaks of the pride of statehood—and no mean state, this!

The iron bones of the ponderable earth shook mightily when Pennsylvania was born. No light day’s business, the bringing forth of this empire! Mountains to rear and valleys to cut; broad rivers to set flowing in generous channels; forests to marshal and meadows to unroll, fair and open and glad with green things growing. Winter, running before the hounds of spring, hides snow like a miser in a myriad pockets of the hills and flies northward across the blue lakes to escape the gleeful laughter of freed springs and singing brooks.

Scratch the crust and you may kindle the world’s hearth; scatter seed and fields were never so green. A fair prospect for the eye, but greater the hope in the heart of man. Fortunate nation this, to have so secure a keystone in the arch of states! The spirits of the pioneers, haunting the hilltops, gaze down in pride upon the teeming valleys. You, sober ones of the broad brims, the axe has gone deep into the forests you came to people; and you in whose blood the Scottish pipes skirl and in whose heads flash the wit of Irish mothers, no land ever received sounder or saner or nobler pilgrims. And you, too, plodding Dutchmen, far-flung drift of the Rhenish Palatinate, you were not so slow and dull after all, but wise in your sowing and reaping. And call the roll of names dear to the Welsh hills and mark the lusty response. The soundest race-stocks in the world are grafted here. Let us be wary of these tales of plunder and corruption. The soil that knew Franklin is not so lightly to be yielded to perdition. Let us have patience, sneering ones; the last lumbering Conestoga has hardly faded into the west, and the making of states is rather more than a day’s pastime! Verily, you paid dearly for this house of your law-makers—marble and bronze and lapis lazuli forsooth! But have a care that Wisdom and Honour are enthroned in those splendid halls—and with no pockets in their togas! Then let him that defileth the temple perish by the sword!

Wayne and Joe sat on a bench in the capitol grounds and fed the squirrels. They had inspected the building with care and Joe pronounced it good. The mood of depression with which Wayne had left home clung to him, but Joe, watching him narrowly, felt that the cloud was less dark to-day.

“This is nice grass,” Joe observed. “I wonder why town grass is always nicer than country grass?”

Wayne smiled, and Joe was encouraged.

“You rankest of cockneys! There was good grass in the world before the day of lawn mowers. What do you think we’re going to do now?”

This question had troubled Joe since their flight. He had an immense respect for Wayne; it was inconceivable that Mr. Wayne Craighill, a gentleman of property, a member of clubs, and a person otherwise indulged and favoured by Fortune, should not weary of this idle adventure and go home. He was confident that his companion would come to himself soon, but he would follow him to the world’s end. Just now, as evening stole over the town, Joe was hungry and Wayne’s indifference to the stomach’s pinch was inexplicable. He did not dare propose that they seek food. Wayne was chief of the expedition and it was not for a mere private in the ranks to make suggestions.

“Did you ever try tramping?” Wayne asked presently.

“I can’t say that I ever did, sir. You mean followin’ the railroad and dodgin’ the cops? Sleepin’ in barns and jails and takin’ a hand-out and a dog-bite at back doors. I ain’t choosy, but I ain’t for it, Mr. Wayne. I like the varnished cars myself.”

Wayne did not debate the matter. He did not see his future clearly; the world was bitter in his mouth. He was fumbling the alphabet of life like a child with lettered blocks, soberly piling them in false positions with the X of unknown quantity in the middle. Once more he had suffered defeat at his father’s hands. The newspaper accounts of Andrew Gregory’s death, on which he had pounced the day after his flight, had been the briefest: he had dropped dead while calling at the home of his old friend, Roger Craighill! Cheated again in satisfying his hatred of his father, the knowledge that Roger Craighill had lied to the doctors was poor consolation. He had submitted himself, a willing Isaac, to be laid on Abraham’s altar, but the right to perish had been denied him. He was utterly morbid; there was no health in him. He was still, in Stoddard’s phrase, a man in search of his own soul, though he did not know it. He had stood between the pillars of life without power to shake them down. He sat, as it were, on the steps beneath the high arch, a defeated Samson. But he would never go back; that was definitely determined; and by continuing his exile he might perhaps intensify his father’s penitence, for Roger Craighill had, he assumed, some sort of conscience that would rest uneasy under the suppressed fact that he had laid violent hands on Andrew Gregory.

He felt, at times, a pity for his father’s wife. She knew! And a man of less imagination could not have failed to picture the new relations of Roger Craighill and his wife with the common knowledge of that night hanging over them. There were people who might feel his loss out of their world; there were Wingfield and Walsh, and there was Paddock—he believed they would be sorry and miss him, but one man more or less in the grand sum of things is nothing. He had failed in good as in evil intentions—failed even Jean who had asked him to care for her grandfather and save him from any such catastrophe as that which must now have brought misery upon her, for the old man’s death had undoubtedly interrupted her work, and she must hate him for his worthlessness. He accepted his fate sullenly; his life was ill-starred, its ordering futile.

He recalled Joe from his contemplation of the squirrels and they went to a hotel that Joe had known in other days, and lodged for the night. Wayne had let his beard grow, and his clothes were the worse for rain and dust. But the differences between them were reconciled by these changes, and they looked like two mechanics in search of employment. The thousand dollars with which Wayne had left home had melted slowly. The bulk of the small bills was an embarrassment and he divided them with Joe.

The idea of losing himself in the world, of wandering free in the spring weather, took hold of his fancy. He had watched tramps from car windows with indifference or contempt, but he had read of men of wisdom who forsook the life to which they were born for the open road. Perhaps in the general sifting processes of nature and life this had been his predestined fate! He did not care one way or another. He was willing that henceforth Fate should shake the dice and he would abide by the decision. The lords of destiny might pass any judgment they liked upon him: he was Wayne Craighill, and he would make no defense to any indictments they might lodge against him in their high tribunal.

He bought a pipe as better suited to his new rôle as a man of the road and they set out for a walk in the streets of Harrisburg. Laughter flashed out from open windows; boys and girls went sweet-hearting through the quiet streets; gay speech, floating out from verandas and doorsteps, contributed to the sense of spring. A girl’s voice, singing to the strumming of a banjo, gave him a twinge of heartache. He was an alien in a strange land and the openness and simplicity and sweetness of the town life drove in upon him the realization of his own detachment from the world of order and peace. They went down to the river and listened to the subdued murmur of the Susquehanna moving seaward under the stars.

Wayne suddenly remembered Joe, sprawled on the grass beside him.

“See here, Joe, you’re a good fellow and you’ve been bully in standing by me. But you’d better cut loose here. You must go back home to your job. It’s not square to drag you along with me; I’m a busted community and I don’t know where I’m going to land. I’m not ready to go home yet—you ought to understand that.”

“I’ve signed my papers,” replied Joe. “I’m not playin’ for my release. I’m not much stuck on walkin’, but if that’s the sport, I’m in. If it’s crackin’ safes or burnin’ barns I’ll divide the job. I’m no quitter.”

Wayne said nothing, but he laid his hand for a moment on Joe’s arm.

They went back to the hotel—not of the best—where they played billiards for an hour and went to bed. Wayne did not know it, but Joe watched until well past midnight to make sure that Wayne did not go down to the bar; then he scrawled and mailed a postal card to Paddock.

“All O.K. and sober. Don’t follow; I’m on the job”; a message which Paddock bore promptly to Wingfield who passed it on to Walsh. Poor Paddock! His sad little smile gained in pathos those days! Wingfield at the Allequippa was better let alone; he leaned on Walsh, who had found a new and blacker cigar, and would not speak of Wayne.

“We’ll leave the machine here until we want it again,” said Wayne in the morning. “And we can express the suit cases to the next stop. We’ll travel incog, as Jones and Smith. I’ll match for the Smith; it’s a name I’ve always admired.”

He flipped a coin and pronounced himself Jones.

“Where shall we send the stuff?” asked Joe.

The porter was at that moment announcing a train in the hotel office and Wayne caught a name.

“Send it to Gettysburg,” he said.

They stepped into the street and were at once launched upon their expedition. A shower in the early morning had laid the dust and sweetened the air; the sky was never bluer; the young leaves brightened in the sun; the horizons were wistful with the hope and faith of May. The country silence soon enwrapt them like a balm. Joe began to whistle but gave it up. He looked back upon the haze that hung above the capitol and was homesick for paved ground and the buzz of trolleys.

“It’s kind o’ lonesome,” he observed, so plaintively that Wayne laughed.

“Oh, you’ll begin to like it after a while. When you get used to travelling this way you won’t buy any more railroad tickets. I’ve read books about people who walked everywhere—all over Europe—because it’s the best way to see the country.”

“I guess we’re more likely to write home for money. I wonder if they wouldn’t give us a bite at that house over there.”

“Not much they won’t! You’ve got to be very regular at meals when you go to tramping and, besides, it isn’t ten o’clock yet.”

“It would be nice if apples were ripe. We tackled it at the wrong season for fruit. I think I could eat raw lettuce out of that garden.”

For the greater part Wayne trudged in silence. They paused now and then to rest and beside a little creek they cut themselves sticks. Morning was never so long and at eleven o’clock Joe declared himself famishing and Wayne mercifully agreed to seek food.

“I’ll tackle this house,” suggested Joe, “and try the dog’s teeth, but I’ve always liked these pants,” he added ruefully.

“As we’re young at the game we’ll omit that feature of the tramping business,” Wayne replied. “For to-day we will be two scientists studying the farming methods of the country. We will pay for our dinner and save our trousers.”

They chose the largest farmhouse in sight, made their appeal, and dined at the family table. Wayne paid generously for their entertainment and smoked a pipe with the farmer, who gave them permission to sleep in his barn. In the morning they dipped themselves in the neighbouring creek and paid for lodging and breakfast at a house farther on. They were a little footsore, but finding that Wayne had no intention of submitting himself to the indignities suffered by professional tramps, Joe went forward in livelier spirits. He was not without his pride, and he was ambitious that his hero should be respectable. At intervals Wayne chaffed him in his old familiar fashion, and this brought Joe almost to singing pitch.

“I guess this is all right,” he vouchsafed, as they lounged in the shade and ate a luncheon purchased at a country store. A pail of milk procured at a farmhouse graced their banquet. Sobriety, Joe reflected, was assured so long as this life continued.

They preferred haymows to the beds that were offered them, and when it was found that they paid their way no one denied them. It grew intensely hot on the second day, and at night a thunder-storm swept the land with loud cannonading. The lightning glowed at the cracks of the loft where they had found lodging; it seemed at times that the barn was wrapt in flame. They slept late the next morning, breakfasted and resumed their leisurely course. They rested often and indulged in siestas of length at noon. The wind and sun tanned them; Wayne with his reddish beard was hardly the man we have seen at the Allequippa Club.

They came upon a becalmed automobile in which a gentleman and a number of ladies were touring to Washington. The party was chafing at the enforced delay; and the two wanderers promptly shed their coats and lent assistance. When the damage was repaired the gentleman appraised their services and tendered payment. Joe, with scornful rejection on his tongue, was surprised to see Wayne accept the bill and lift his cap in acknowledgment. They watched the car gather speed and dip out of sight beyond a hill.

“I didn’t suppose we’d take tips,” remarked Joe meekly, looking at a two-dollar bill in his own hand.

“My dear companion in misery, we gentlemen of the road refuse nothing! And besides, it was cheap at the price. Any well-regulated garage would have taxed him ten dollars. And it pleased me to see that I’m so well disguised. I’ve sat at the same table with that man and he didn’t know me from Adam. The barber and tailor make us, Joe—remember that I said so. I’m learning something new every day and by the time we’ve walked around the world we’ll be educated men.”

“I’m afraid you’d lose me,” grinned Joe. “I heard a train whistle a while ago. It almost gave me heart disease.”

There were times now when Wayne seemed himself, but he was more and more inexplicable. When he sprawled under a tree during their long noonings Joe knew that he did not sleep, but stared silently at the sky; and as they trudged along many hours would pass in utter silence. And so, by devious ways, they came to Gettysburg.

They had gone astray many times when, at nightfall, they came unawares upon the battlefield. A fog born of recent rains rose from the wet earth and hung in broken clouds. They paused beside a fence, uncertain of directions. Suddenly a cry from Joe arrested Wayne’s attention. Near at hand a horse and rider seemed flung upward into the misty starlight. The erect figure of the man, the arched neck and upraised foot of the horse, were startlingly vivid. The weird spectacle held them fascinated. At any moment the mystical horseman might take flight and gallop into the enfolding fog in pursuit of his lost legion. Other figures, equally fantastical, and ghostly monuments rose against the starry sky out of the drifting fog-ribbons. Joe, staring about, cried aloud in fear as he stumbled against a cannon. Wayne explained that they were on the Gettysburg battlefield and that these were memorials of dead soldiers.

“It’s too woozy for me,” declared Joe, and they sought the town and found their bags and lodging for the night.

They woke in the morning to find it Memorial Day, with excursions of veterans pouring in for a celebration. They followed their own devices, keeping away from the crowd, and late in the afternoon rested at the foot of Warren’s statue on Little Round Top. Wayne had bought a map and he opened it to fix the lines of Pickett’s assault. His blood tingled as he grasped the significance of the famous charge, gazing down upon the field of death. He explained it to Joe and they rose as by one impulse and took off their caps.

“They were men, Joe; it takes men with the real stuff in them to do that.”

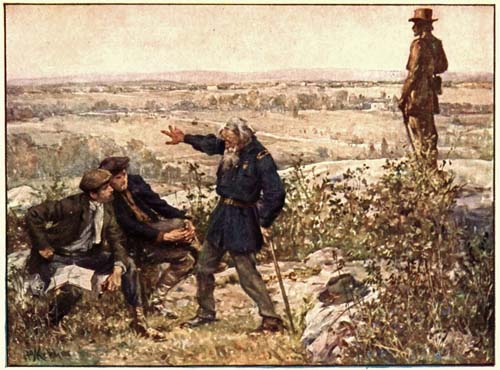

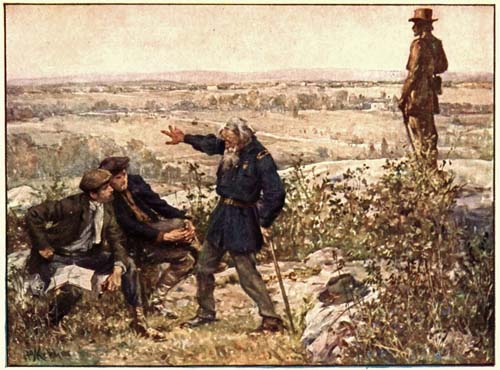

Scattered over the field, sightseers followed the events of the long-vanished July days. An old man in the blue blouse of the Grand Army of the Republic toiled slowly up Little Round Top and stationed himself near them. He was muttering to himself, and so intent upon his own thoughts that he did not see them. He pointed with his hat as though demonstrating some controverted point, and shook his head, and Wayne and Joe eyed him wonderingly. The veteran’s lean figure was erect; he thrust his stick under his arm and looked down upon the battlefield, the wind playing softly in his gray hair. He turned toward Cemetery Ridge and saw the men behind him. A wild look came into his bleared eyes and he grasped Wayne’s arm, whispering:

“It’s in the bugle! It’s in the bugle!”

“You were a soldier in this battle?” asked Wayne, not understanding.

“I was in many battles, young man. It’s the bugle that does the mischief; pluck the heart out of the bugle and drum and men won’t kill each other any more. Many a man I’ve bugled down to death.”

He dropped his head upon his breast. A bird sang in the thicket below. On the heights beyond a bugle sounded, faint as though from a far-off time. The old man shrank away; then he began to speak, in the hoarse, broken voice of age, but coherently, as though reciting an oft-told tale:

“We had a boy captain with beautiful brown eyes, who had left college to go into the army. That boy, with his handful of cavalry, felt bigger than old Napoleon and we were as proud of him as he was of us. Early in the war we were sent out on a scout along the Chickahominy and were going back to our brigade when we ran plump into a bunch of the enemy’s cavalry that had been out feeling our line. They were just coming up out of a ford, and it was a surprise on both sides, but our captain laughed and said:

“‘The charge, trumpeter!’

“I let go with the bugle and we slapped into them right at the edge of the water. There was a bad mess for a few minutes, then back we went with the gray boys at our heels. We fought up and down the road, as though we were only playing a game; sometimes we drove them and then they drove us. On our second dash I felt my horse’s hoof plunk soft onto a dead man, and I remember how queer it made me feel. We had to win that ford, and the other fellows wanted it just as bad as we did. Well, it was nearly dark when we began that foolishness, and a good many of the boys had dropped out of their saddles, and a few horses were running up and down with us, just for company I guess, or because they knew the calls and followed the bugle. I remember how the little moon hung over the trees and the stars came out, but our captain kept up the fight. It was all like a lark, but silly, for we were in between the lines where we might have brought on a general engagement with all the racket we were making. I remember thinking the game would last forever, as we charged and wheeled and flung ourselves at the gray boys; and every time we swung at them again there were more soft thumps where my horse struck dead men. I have dreamed about that a thousand times—the scared little moon, and the rattle of accoutrements and the pounding hoofs, and the yells, and the crack of pistols; but it was mostly the sabre, splashing and cutting. I felt that now I had got the hang of it, it would be just as easy to bugle the stars out of the sky as to sound charge and recall there by the ford. Well, we got the ford all right, but when we splashed through to the other side there was only about half of us left, and I felt sick and giddy when I looked down and saw the little captain was gone and the lieutenant was riding by me where that brown-eyed boy had been.

“That was only the beginning and I got hardened fast enough; but when the war was over I used to wake up at night and think of all the battles I’d fought in, and try to count up the men I had bugled out to die. Then I married and had a home for a while, but my wife died, and those old times began to get bigger and bigger and now I never look back to anything but just those days of the camp, and the fights; and the bugle sings in my ears all the time as though it was calling to the men I sent into battles where they died!”

“War’s an ugly business; somebody has to be killed,” said Wayne kindly, moved to pity by the veteran’s emotion.

“I’ve trumpeted my thousands down to death,” he answered; and then, clearing his throat, he went on:

“I dream every night that I’m on a high place—not here, but a grayish sort of hill with a gray cloud hanging over it, and I look down and see long lines of them marching.”

“Them?” Wayne asked.

“GHOSTS, THE GHOSTS OF DEAD SOLDIERS”

“Ghosts, the ghosts of dead soldiers, marching with their heads bowed down the way tired soldiers march at night. And when one line passes, another trumpeter strikes up and another army of the same tired ghosts follows right after. It’s all mighty still—you never hear any sounds at all except the trumpet, and it’s muffled and choked—not even when the cavalry come along or the artillery. You know how moving guns rumble like thunder when they go along a hard road? Well, you never hear even the cannon, but the cavalry ride with their heads down, like the infantry, and the horses with their noses against their knees almost; and the artillerymen sit on the caissons with their arms folded and their heads bowed as though they were asleep. I can’t make out where they came from or where they are going; they just came out of nowhere and go nowhere—but they never stop coming. And the trumpeters blow back all the men that have ever died in battle since the world began—so that they are years and years passing by—that’s the way it seems in my dream. Then I’m all alone on the hill, and I know it’s my turn to sound the trumpet; and something clicks in my throat when I try to blow, and I can’t make a sound, and as I keep trying and trying I wake up; but I never can make them come. I can’t bring back my dead men out of the dust the way the others did, and I sit up and cry when I remember how I killed them.”

He ceased as abruptly as he had begun, stared fixedly at Wayne and Joe and then slowly descended, muttering and shaking his head. When he was out of sight the two stood silently gazing after him. Wayne drew his hand across his forehead several times before he spoke.

“Men live for things and they die for things. That poor old fellow has lost his mind brooding over the horror of war. They didn’t do it for themselves—the men who fought that war—they did it for the country, and for you and me who weren’t born. I wonder—I wonder how it would be to do something just once that was for somebody else?”

Then he remembered what Jean had said to him in his father’s library, that we must serve ourselves before we attempt to serve others. He applied this to himself tentatively, wondering whether any philosophy was really applicable to his case. Joe spoke to him; he wanted to discuss the old soldier’s story, but Wayne did not heed him. He was looking dreamily down upon the tranquil landscape. Then he slapped his hands together as was his way when a new thought took hold of him.

“Joe.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I wonder how it would seem to go to work.”

“Well, there’s always your roost in the high buildin’ and buttons to press for the slaves,” suggested Joe cheerfully.

“Don’t be a fool, Joe. I mean work—the kind that real men do, digging or planting, or any kind of thing that breaks your back and makes you dead tired—the workmen do who would do that——” and he levelled his arm toward the field where Pickett’s legion had charged through the hail-swept wheat field.

Joe was not equal to this; here was a man born immune from the primal curse, first turning tramp and sleeping in barns, and now soberly threatening to go to work. So unaccountable a frame of mind put Joe on guard; very likely Wayne was preparing for another spree and Joe was troubled.

The next morning Wayne, without explanation, laid their course toward the north; but Joe thought he knew where they were going.