3. The 7 Factors that Influence User Experience

Read time: 4 mins

User Experience (UX) is critical to the success or failure of a product in the market, but what do we mean by UX? All too often, UX is confused with usability, which describes how easy a product is to use. While it is true that UX as a discipline began with usability, UX has grown to accommodate much more than usability, and paying attention to all facets of UX in order to deliver successful products to market is vital.

“To be a great designer, you need to look a little deeper into how people think and act.”

— Paul Boag, Co-Founder of Headscape Limited

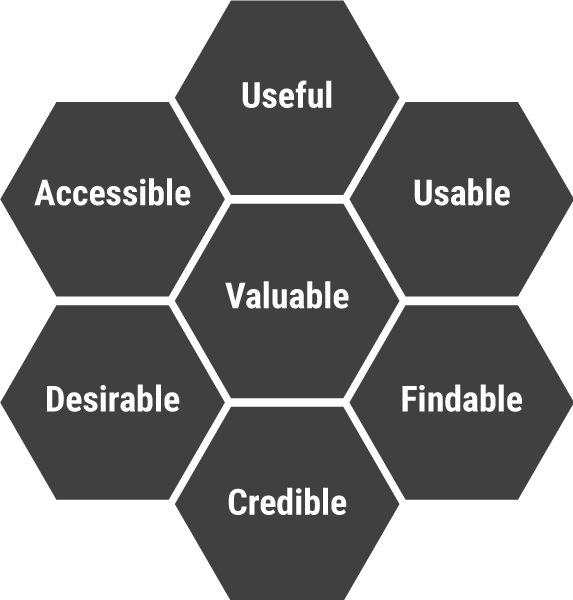

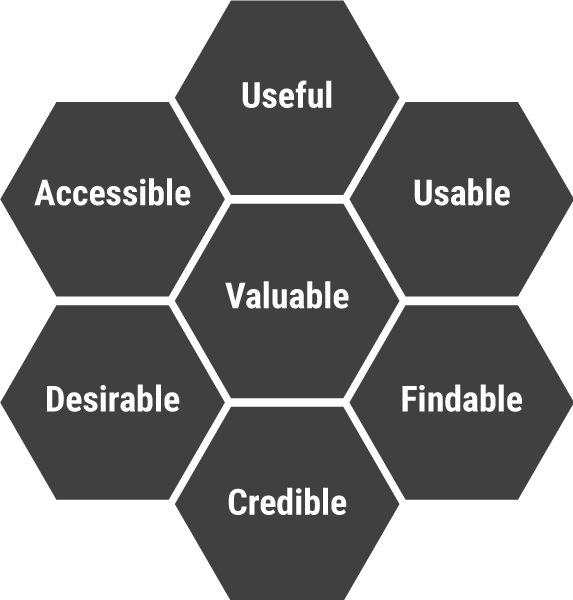

There are seven factors that describe user experience, according to Peter Morville, a pioneer in the UX field who has written several best-selling books and advises many Fortune 500 companies on UX. Morville arranged the seven factors into the ‘User Experience Honeycomb’, which became a famous tool from which to understand UX design.

The 7 factors are:

- Useful

- Usable

- Findable

- Credible

- Desirable

- Accessible

- Valuable

Let’s take a look at each factor in turn and what it means for the overall user experience:

1. Useful

If a product isn’t useful to someone, why would you want to bring it to market? If it has no purpose, it is unlikely to be able to compete for attention alongside a market full of purposeful and useful products. It’s worth noting that ‘useful’ is in the eye of the beholder, and things can be deemed ‘useful’ if they deliver non-practical benefits such as fun or aesthetic appeal.

Thus, a computer game or sculpture may be deemed useful even if neither enables a user to accomplish a goal that others find meaningful. In the former case, a teenager may be using the game to vent angst after a hard exam at college; in the latter, an art gallery visitor may ‘use’ the sculpture to educate herself on the artist’s technique or tradition, gaining spiritual pleasure at the same time from viewing it.

2. Usable

Usability is concerned with enabling users to achieve their end objective with a product effectively and efficiently. A computer game which requires three sets of control pads is unlikely to be usable as people, for the time being at least, only tend to have two hands.

Products can succeed if they are not usable, but they are less likely to do so. Poor usability is often associated with the very first generation of a product—think the first generation of MP3 players, which have since lost their market share to the more usable iPod. The iPod wasn’t the first MP3 player, but it was the first—in a UX sense, at least—truly usable MP3 player.

3. Findable

Findable refers to the idea that the product must be easy to find, and in the instance of digital and information products, the content within them must be easy to find, too. The reason is quite simple: if you cannot find the content you want in a website, you’re going to stop browsing it.

If you picked up a newspaper and all the stories within it were allocated page space at random, rather than being organized into sections such as Sport, Entertainment, Business, etc., you would probably find reading the newspaper a very frustrating experience. The same is true of hunting down LPs in a vintage music store—while some may find rifling through randomly stocked racks of assorted artists’ offerings part of the fun and ritual, many of us would rather scan through alphabetically arranged sections, buy what we want, get out and get on with our day. Time tends to be precious for most humans, thanks largely to a little factor called a ‘limited lifespan’. Findability is thus vital to the user experience of many products.

4. Credible

Twenty-first-century users aren’t going to give you a second chance to fool them—there are plenty of alternatives in nearly every field for them to choose a credible product provider. They can and will leave in a matter of seconds and clicks unless you give them reason to stay.

Credibility relates to the ability of the user to trust in the product that you’ve provided—not just that it does the job it is supposed to do, but also that it will last for a reasonable amount of time and that the information provided with it is accurate and fit-for-purpose.

It is nearly impossible to deliver a user experience if the users think the product creator is a lying clown with bad intentions—they’ll take their business elsewhere instead, very quickly and with very clear memories of the impression that creator left in them. Incidentally, they may well tell others, either in passing or more intentionally, in the form of feedback, so as to warn would-be customers, or ‘victims’ as they would view them.

5. Desirable

Skoda and Porsche both make cars. Both brands are, to some extent, useful, usable, findable, accessible, credible and valuable—but Porsche is much more desirable than Skoda. This is not to say that Skoda is undesirable; they have sold a lot of cars. However, given a choice of a new Porsche or Skoda for free, most people will opt for the Porsche.

Desirability is conveyed in design through branding, image, identity, aesthetics, and emotional design. The more desirable a product is, the more likely it is that the user who has it will brag about it and create desire in other users. Yes, we’re talking about envy here; whilst we can salute Skoda’s indomitable spirit—not least for having made very innovative strides and made the most of resources behind the Iron Curtain—we’ll tend to yearn after the other car here, the one that screams ‘Look at me!’ and is pure power and affluence on four wheels.

Author/Copyright holder: slayer. Copyright terms and license: CC BY 2.0

Porsche, founded in 1931, is synonymous with power and style. As a brand, it embodies opulence and glamour, commanding heads to turn on chic, urban streets. Skoda, despite having a nearly 40-year head start in the business, doesn’t pluck the same chord in the popular psyche.

6. Accessible

Sadly, accessibility often gets lost in the mix when creating user experiences. Accessibility is about providing an experience which can be accessed by users with a full range of abilities—this includes those who are disabled in some respect, such as the hearing, vision, motion, or learning impaired.

Designing for accessibility is often seen by companies as a waste of money—the reason being the enduring misconception that people with disabilities make up a small segment of the population. In fact, according to the census data in the United States, at least 19% of people had a disability in 2010, and it is likely that this number is higher in less developed nations.

That’s one in five people in the audience for your product who may not be able to use it if it’s not accessible—or 20% of your total market!

It’s also worth remembering that when you design for accessibility, you will often find that you create products that are easier for everyone to use, not just those with disabilities. Don’t neglect accessibility in the user experience; it’s not just about showing courtesy and decency—it’s about heeding common sense, too!

Finally, accessible design is now a legal obligation in many jurisdictions, such as the EU. Failure to deliver accessibility in designs may result in fines. Sadly, this obligation is not being enforced as often as it should be; all the same, the road of progress lies before us.

Author/Copyright holder: Birmingham Culture. Copyright terms and license: CC BY 2.0

Making products accessible to users who have various levels of ability is vital. ‘Disability’ is not a dirty word—it’s a condition that could well apply to all humans, at least to a very slight, almost imperceptible degree regarding any of a person’s five senses, physique, cognition, etc.

7. Valuable

Finally, the product must deliver value. It must deliver value to the business which creates it and to the user who buys or uses it. Without value, it is likely that any initial success of a product will eventually corrode as the realities of natural economics start to undermine it.

As designers, we should bear in mind that value is one of the key influences on purchasing decisions. A $100 product that solves a $10,000 problem is one that is likely to succeed; a $10,000 product that solves a $100 problem is far less likely to do so.

The Take Away

The success of a product depends on more than utility and usability alone. Products which are usable, useful, findable, accessible, credible, valuable and desirable are much more likely to succeed in the market place. So, factor all of these considerations into your designs—you won’t just safeguard what you’re selling from obscurity; you’ll vastly increase your chances of establishing a brand name as you watch the conversion rate climb, too.

References & Where to Learn More

The US census results for disability – https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/miscellaneous/cb12-134.html

Peter Morville’s original work on the 7 facets of user experience may be found here – http://semanticstudios.com/user_experience_design/

User Experience: The Beginner’s Guide

Beginner course

User experience, or UX, has been a buzzword since about 2005—and customer intelligence agency Walker predicts that it will overtake price and product as the key brand differentiator by 2020. Chances are, you’ve heard of the term, or even have it written somewhere on your portfolio. But there’s also a good chance that you occasionally feel unsure of what the term “user experience” actually encompasses. Through User Experience: The Beginner’s Guide, you will gain a thorough understanding of the various design principles that come together to create a user’s experience when using a product or service. You’ll learn the value UX design brings to a project, and what areas you must consider when you want to design outstanding user experiences. This course is a great introduction to the ever-evolving and growing field of user experience, and a fantastic way to start the next chapter of your career progression.

Learn more about this course

How Course Takers Have Benefited

“I learnt a good deal from various lesson items and design examples. I also appreciate how repeating key topics helped me memorize them and kept me well involved. Thank you.”

— Veena Sankaranarayanan, Australia

“Perfect balance between knowledge, capacity to transmit the knowledge and sense of humor.”

— Juan Xabier Monjas Campandegui, Spain

“I liked how the instructors were able to link what they are saying to real life scenarios, it helped to consolidate learning for me.”

— Prince Onyeabor, Nigeria

View the course curriculum