foundation of our science.

Systema Naturae (1735), trans. M. S. J. Engel-Ledeboer and H. Engel (1964)

Chapter 7 – FIFA World Cup 2026

While it may seem unnecessary to structure the data about a football tournament as a database when a single chart can do the same job competently, a database can be used to collect searchable data about multiple instances of a competition thus allowing reasonable comparisons e.g., of a team’s performances over many different World Cup tournaments.

The 2026 tournament data used are that from the Bid United (the successful North American bid) site.

For the 2026 tournament, to get to one of the two apex games (final or third place game), a team will have to do well in the group phase and then win all its games until the semi-finals.

(N.B. the names used below for the tournaments and their components may not be what FIFA have used or may use but that is of no consequence in this analysis. However, the use of names instead of meaningless text strings as component-attributes of primary keys means that these names cannot be changed.)

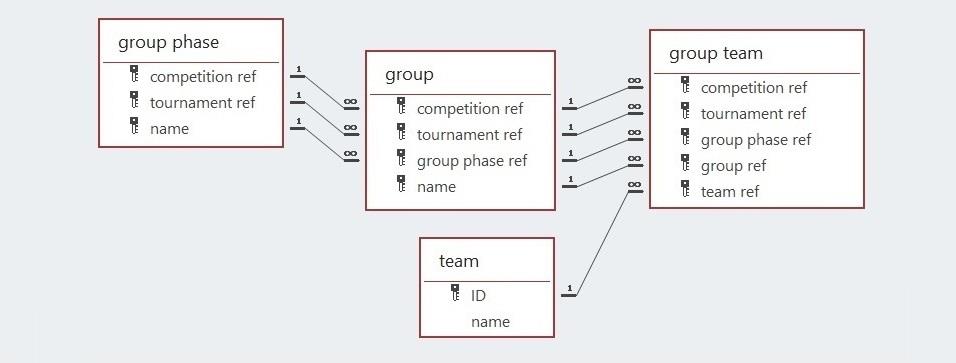

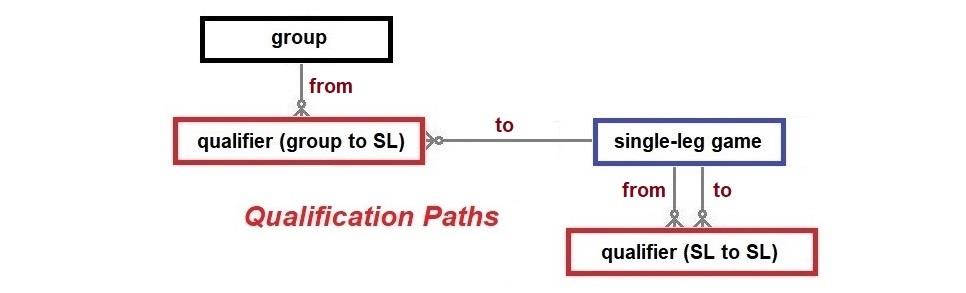

The 48 teams who will start the tournament will be assigned to 12 groups. Further information about the publication of the logistical details (e.g., venues and start times of the 102 games and the allocation of the qualifiers to groups) can be obtained from the Bid United site. To enable the specification of the criteria for progress, identifiers will have to be assigned to each group and single-leg game. This is because the two types of progress catered for by this model are that from a group to a single-leg game and that from one single-leg phase to the next.

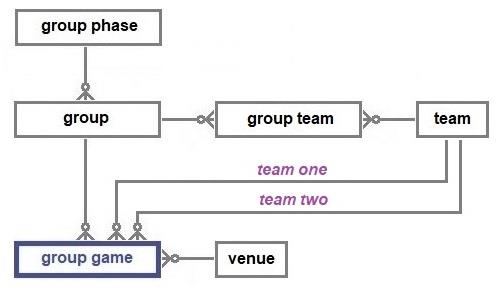

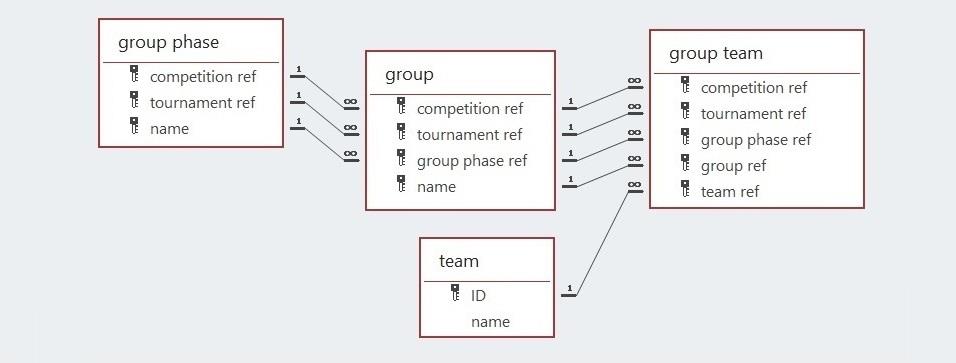

The twelve groups are assumed here to be named using the letters A through to L, a common naming convention. The model above represents the data structure necessary to record the teams in each group.

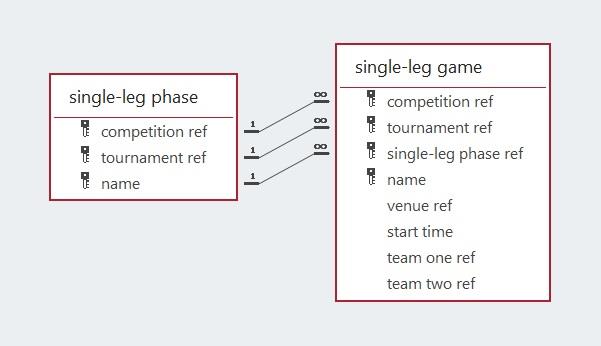

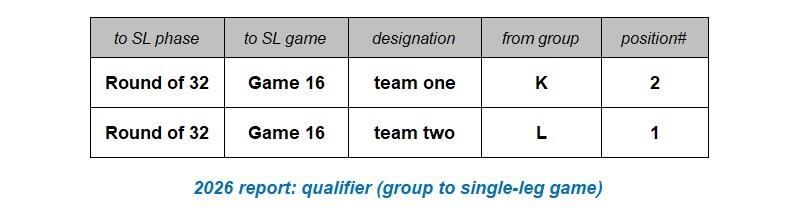

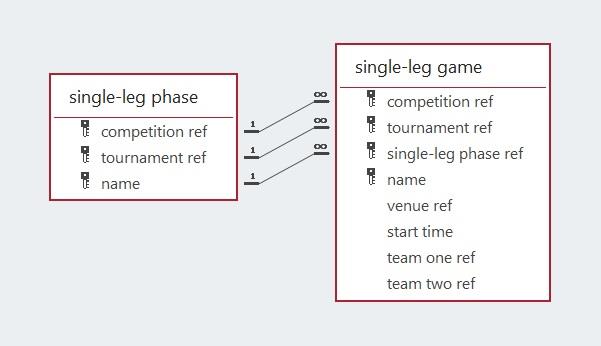

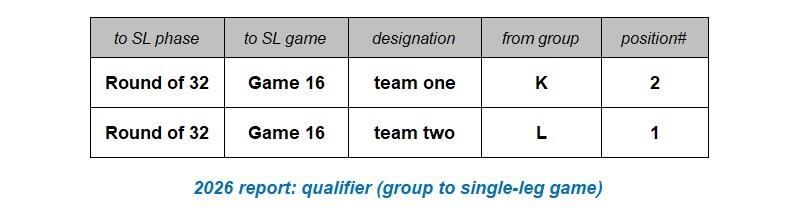

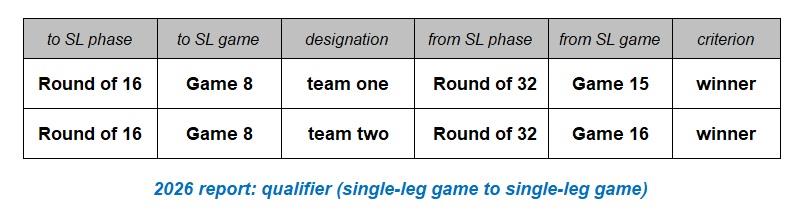

After the completion of the group phase, thirty-two teams progress to the first of the single-leg phases, the Round of 32. In this database, all games are named using the format “Game n” where n is an integer, e.g., Game 16.

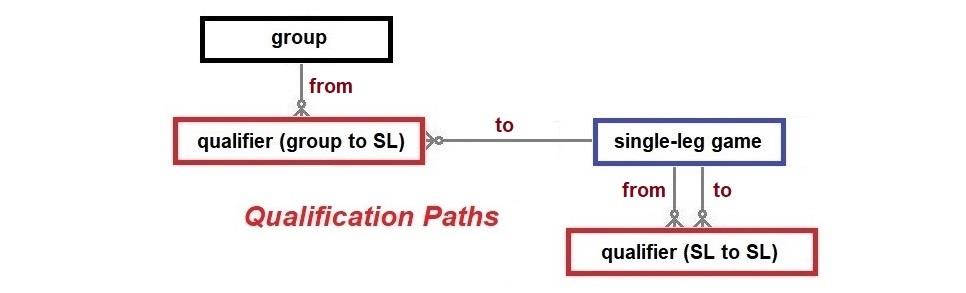

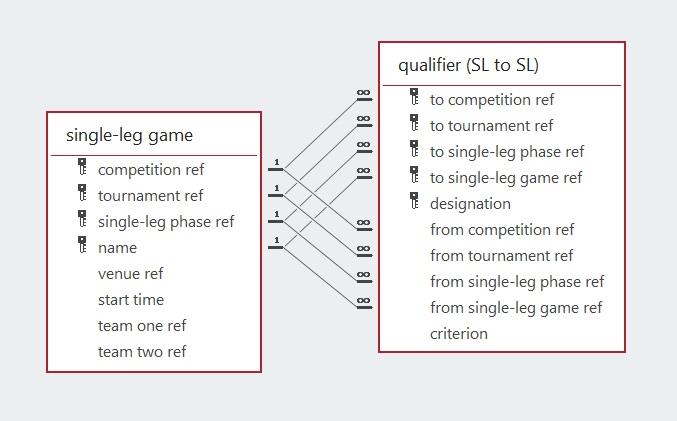

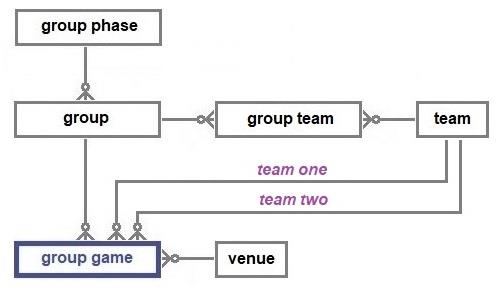

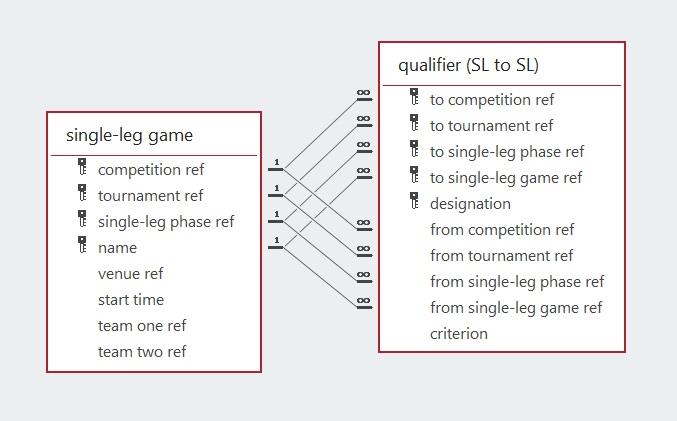

The model below represents the use of the group position (winner, runner-up, or one of the best eight of the third-placed teams in the twelve groups) necessary for a team to qualify to play in the single-leg phase of 32 knock-out games. The model also includes the specification of the qualifying team’s designation as either team one or team two, even though the concept of home or away teams is not used in these tournaments. Eight of the thirty-two qualifiers for the Round of 32 can only be specified after the groups with the eight best performing third placed teams are known. The model and report that follows is that specifying the qualifiers from a single-leg game to the next single-leg phase. The reports below use test data as the required information has not been made available yet. The reports have also dispensed with the common attributes, i.e., the competition and tournament references.

With respect to the apex games, while the self-evident qualification criteria from the semi-finals do not need to be specified, it will be necessary to designate the qualifying teams as either team one or team two for logistical reasons (not shown).

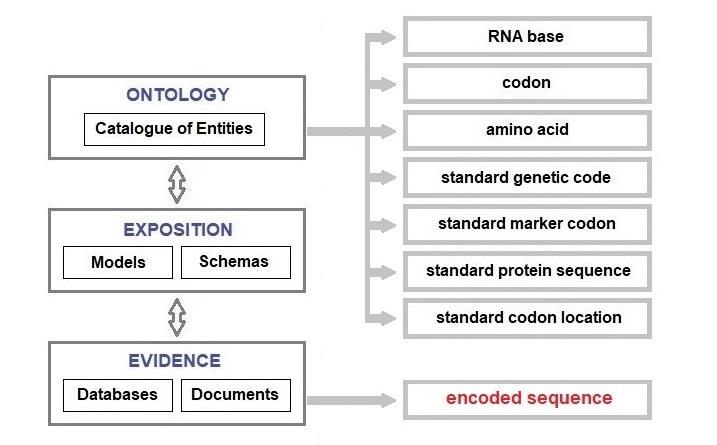

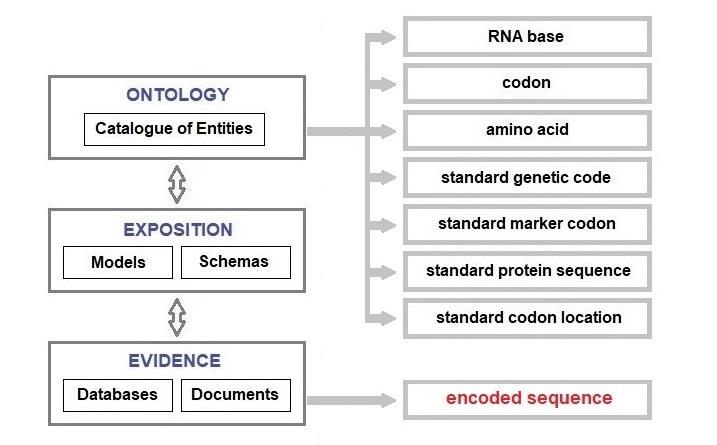

Chapter 8 – Protein Sequences

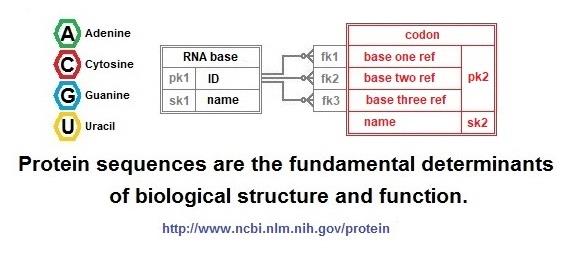

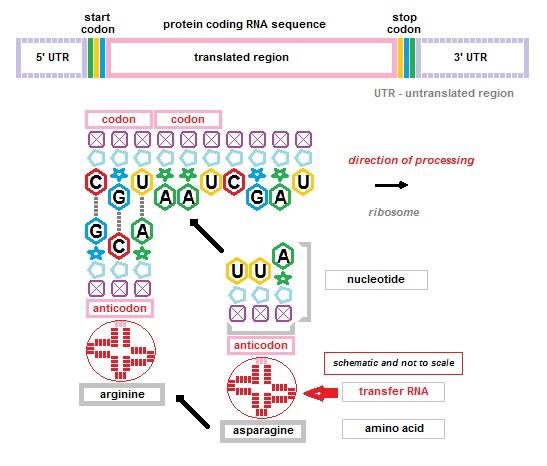

In 1902, Emil Fischer and Franz Hofmeister independently and simultaneously proposed that proteins are the result of the formation of peptide bonds between amino acids in a linear structure. In this discussion, the term protein sequence will be used to describe a linear unbranched chain of amino acids. This chapter provides information about the standard genetic code and the encoding of a human protein. It provides some of the evidence observed underpinning the 'central dogma of

molecular biology' (Francis Crick 1970), i.e., DNA makes RNA makes protein.

The model discussed here does not include the 24 known (at the time of writing) non-standard genetic

codes nor the involvement of the exotic amino acids selenocysteine and pyrrolysine. It does, however, show how transfer RNA performs the function of a foreign key by implementing a relationship between a codon and an amino acid thus enabling the manufacture of protein sequences by ribosomes.

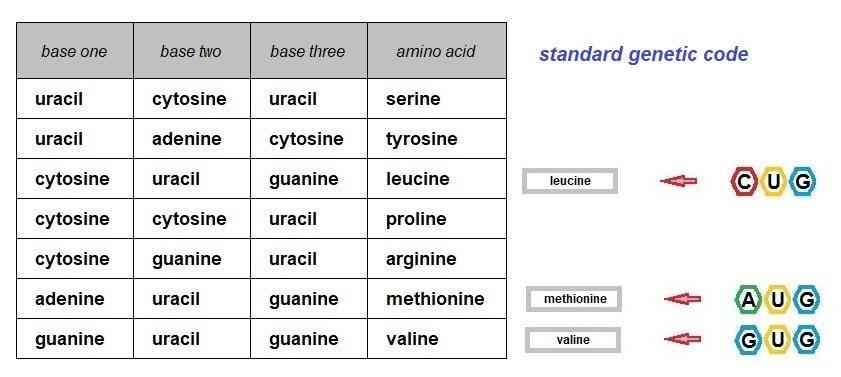

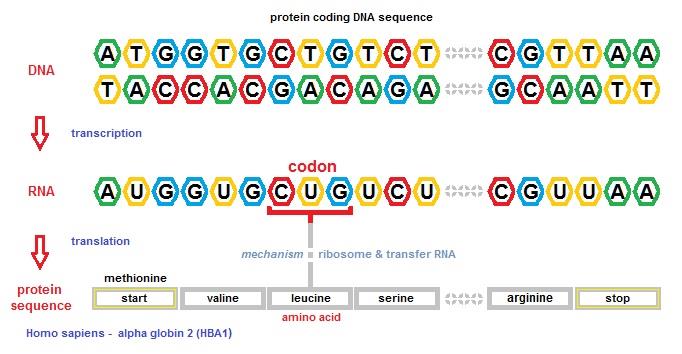

DNA encodes protein sequences and other genes e.g., functional RNA. The encoding of the sequence of amino acids in a protein sequence is done using the 4 DNA nucleobases, (adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine) arranged in groups of three, the codon. The codon defines the sixty-four arrangements that make the encoding mechanism explicable. Codons also include those that function as start and stop markers of the encoded protein sequences.

Marshall Warren Nirenberg, Har Gobind Khorana and Robert William Holley were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1968 for deciphering the genetic code. The encoded sequences of amino acids in DNA are transmitted from one generation of cells to the next via a number of different regenerative and reproductive techniques, all involving the replication of DNA, though with random

mutations.

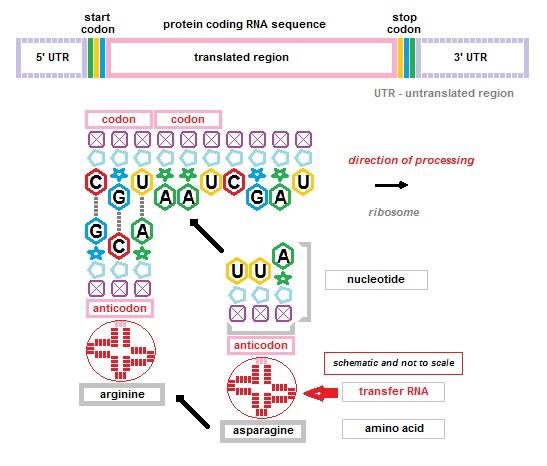

Transfer RNA associates each type of amino acid with an anticodon. The anticodon uses the complementarity of the bases (A/U and C/G) to add new amino acids to a growing chain of amino acids (see above) with the help of a ribosome until a stop codon is encountered on the messenger RNA.

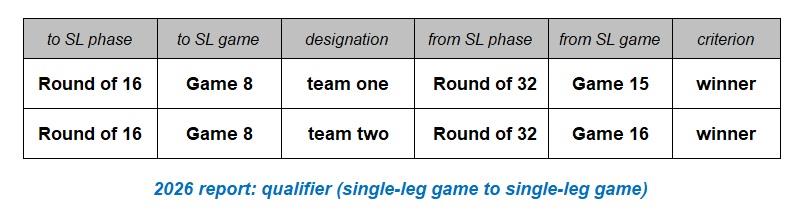

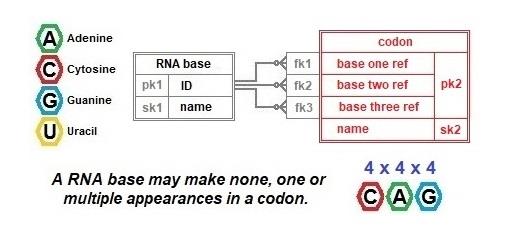

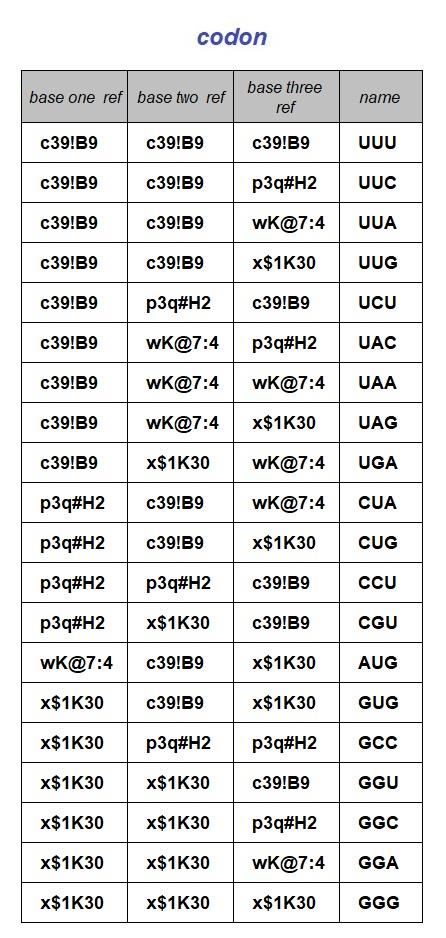

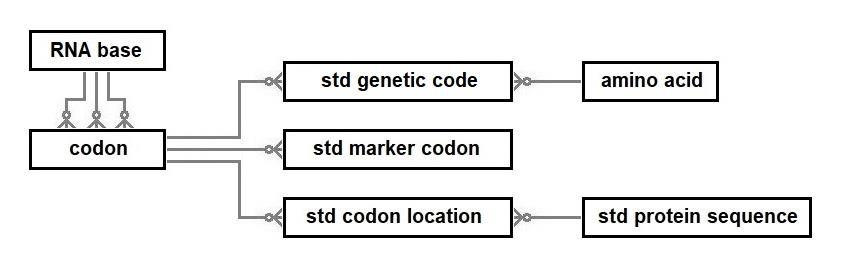

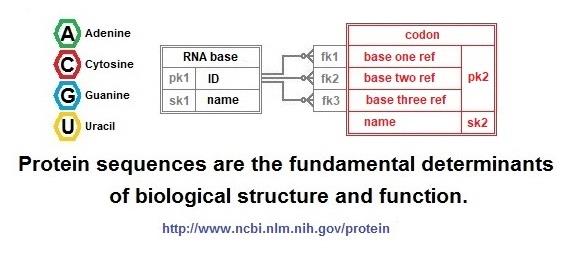

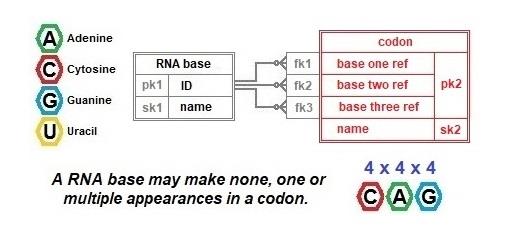

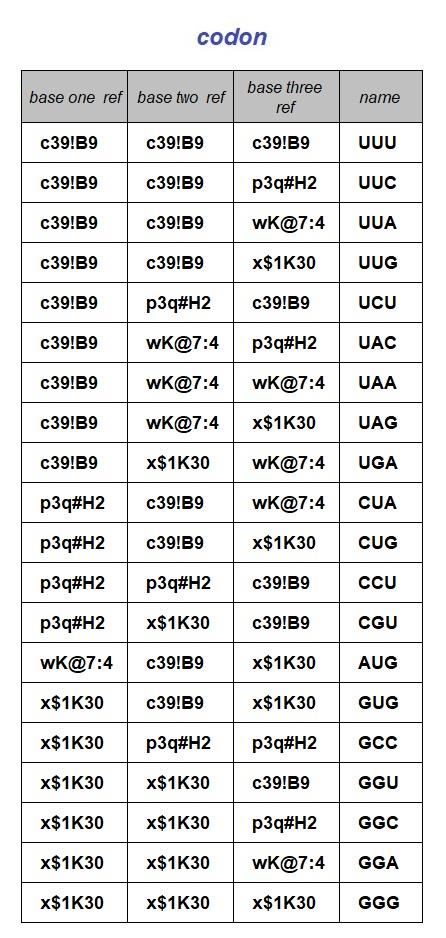

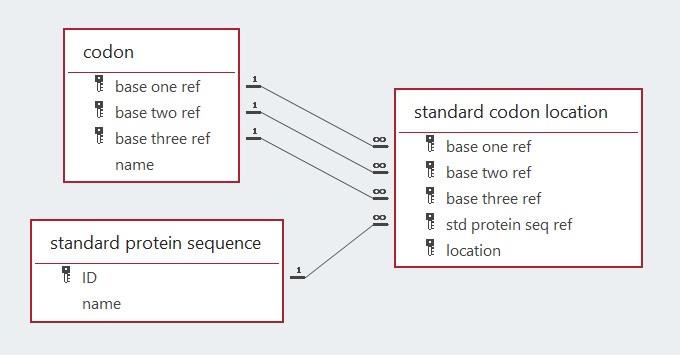

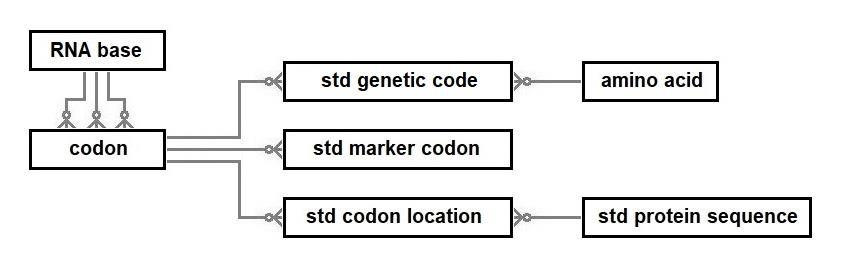

The database proposed below has another illustration of the use of keys to enforce rules. This happens in the definition of a codon. To ensure that only sixty-four codons are specified in the database, a composite primary key using three foreign keys has been defined. The sixty-four possible codons may conduct a total of sixty-seven possible translations when the standard genetic code applies, albeit, depending on the context because of the dual functionality of three of the codons.

As I have no idea of what is happening in academic or commercial genetic research, I have presumed that as far as non-specialists are concerned, the statements above are justified. (The Guardian

newspaper had a report of an artificial pair of protein bases 24 Jan 2017). For information about genetic codes and protein encoding, I have relied pretty much exclusively on the National Center for

Biotechnology Information (thank you NCBI, great material). I have assumed that the NCBI is a trusted authority on this subject.

As an autodidact on this subject, I may be exhibiting the Dunning-Kruger effect insofar as I may not be qualified (i.e. without the required specialist knowledge) to understand the consequences of not modelling other known, obscure and complex relationships between nucleotide sequences and the subsequent translation of codon sequences. That is a risk I took because the model proposed below is meant to explain the protein encoding mechanism and does not purport to describe all relationships between nucleotide sequences and protein synthesis.

On the other hand, you should, of course, independently verify all statements here (nullius in verba) before formulating any view as to the utility or otherwise of the model. Further investigation of non-standard codes and the recoding of some codons will require extensions or amendments to this model, one that is limited to the standard code only. However, even if my model is wrong or incomplete, it is reassuring to know that the mechanisms that transcribe DNA to RNA and then translate the messenger RNA into a sequence of amino acids are understood well enough by other individuals to enable some of them to design processes and tools to use DNA to store non-genetic

data.

Chapter 9 – The Standard Genetic Code

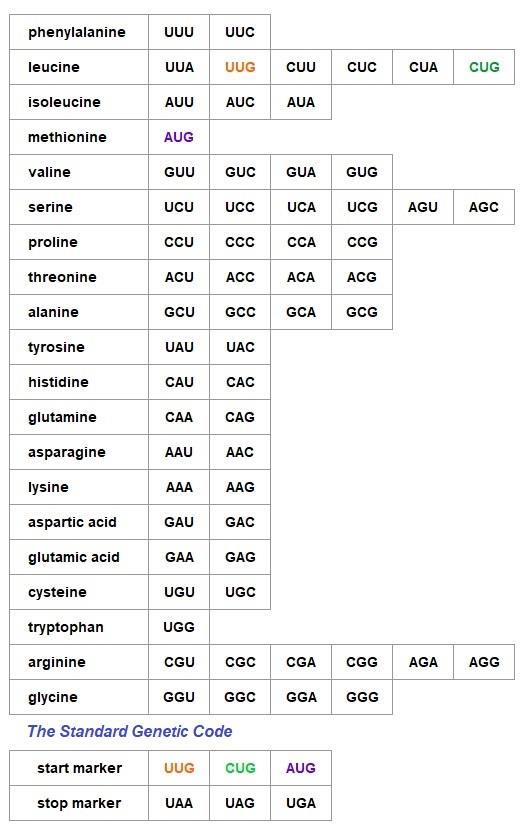

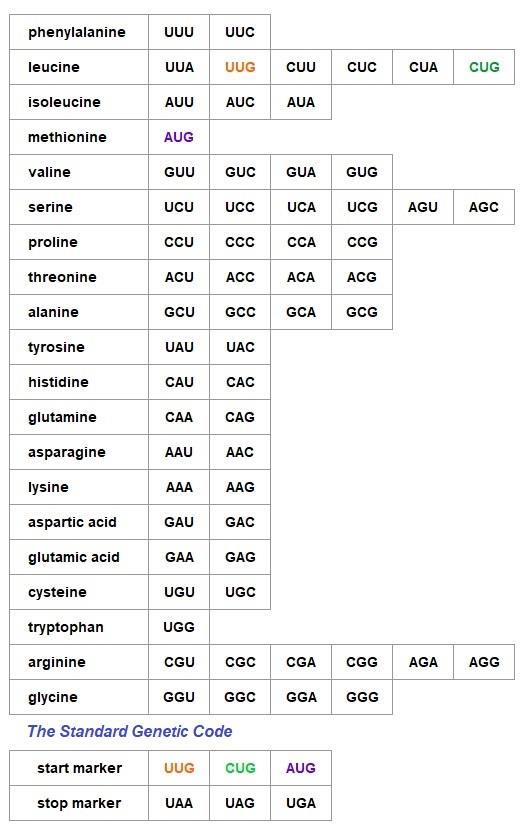

Proteinogenic amino acids may be coded for by none, one or many codons. For example, serine is coded for by six different codons, tryptophan is only coded for by UGG and selenocysteine and pyrrolysine are coded for by none directly. Codons may also code either for start or stop markers.

The following two articles may throw more light on the matter of the non-standard behaviour of codons but there will be no further mention of the non-standard codes nor selenocysteine and pyrrolysine here.

Dual functions of codons in the genetic code (Alexey V. Lobanov, Anton A. Turanov, Dolph L.

Hatfield, and Vadim N. Gladyshev)

Selenocysteine, Pyrrolysine, and the Unique Energy Metabolism of Methanogenic Archaea

(Michael Rother, and Joseph A. Krzycki)

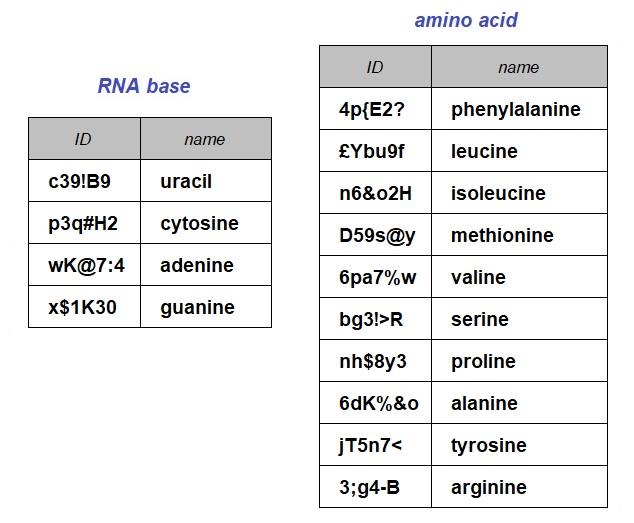

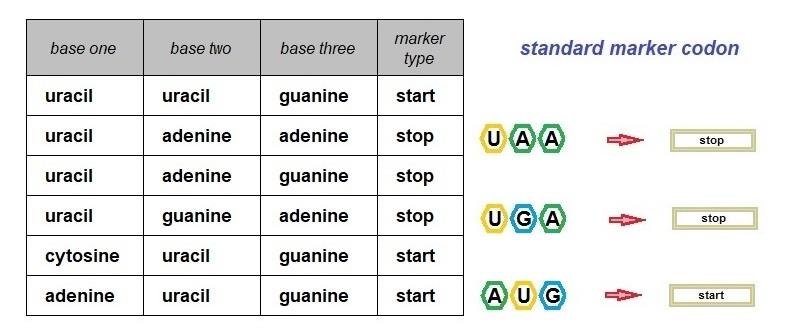

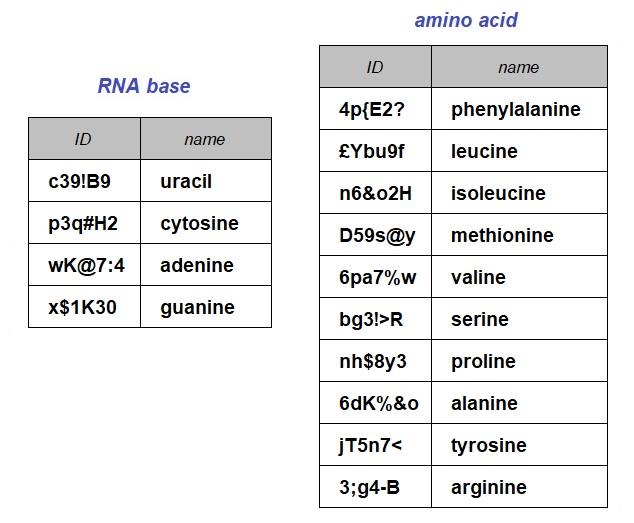

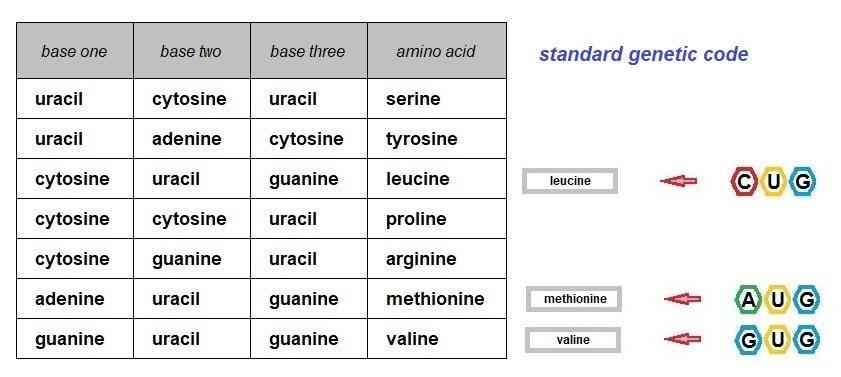

The objective of this data collection exercise is to report on the sequence of amino acids encoded in the DNA by translating the sequence of codons for a protein using the standard genetic code. The tables below provide the 4 RNA bases and some examples of amino acids and codons that feature in the explanation that follows.

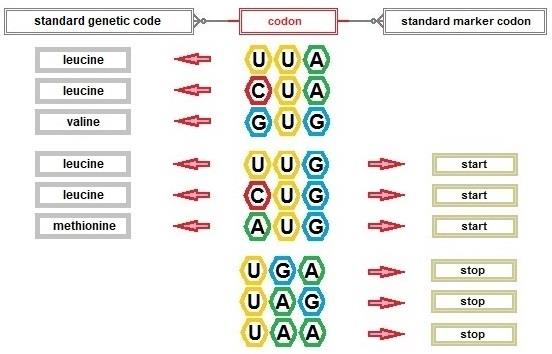

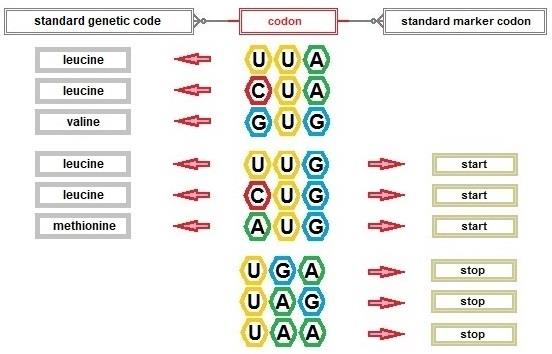

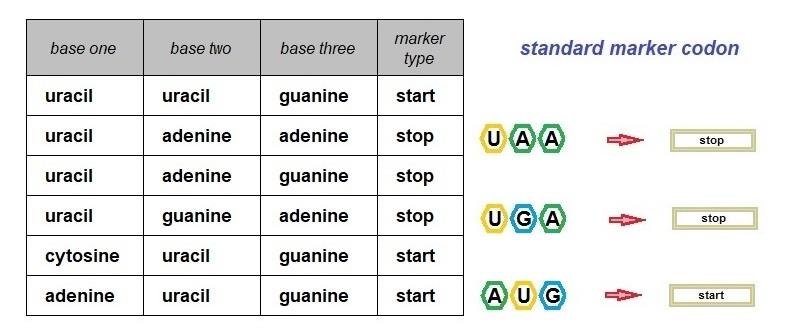

The standard genetic code currently allows initiation from UUG and CUG in addition to AUG . Each of the three codons can function as both an amino acid code and as a start marker in the standard genetic code. This does not cause confusion during protein synthesis because after their first appearance in messenger RNA and before a stop codon is encountered, the three start codons will code for the amino acids shown below.

The above relationships will be implemented as two tables, the sixty-one standard genetic code

table ( the transfer RNA role) and the six standard marker codons table.

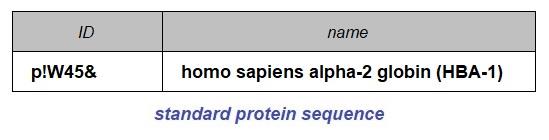

Chapter 10 – Encoded Protein Sequence

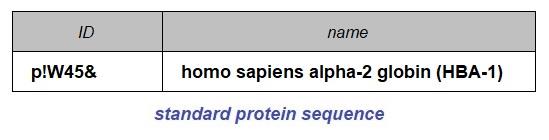

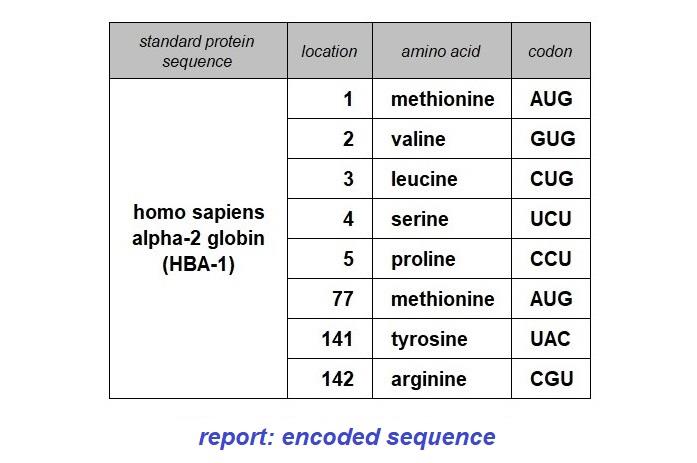

As discussed above, the sequence of amino acids in proteins can be deduced from the location of codons in protein coding nucleic acid sequences. I have categorised protein sequences into standard and non-standard protein sequences depending on whether the standard genetic code applies or if a non-standard genetic code applies. To illustrate how the sequence for a standard protein sequence

is deciphered, I shall use sequence data from the NCBI for the messenger RNA of the human HBA1

gene. The protein sequence is homo sapiens alpha-2 globin.

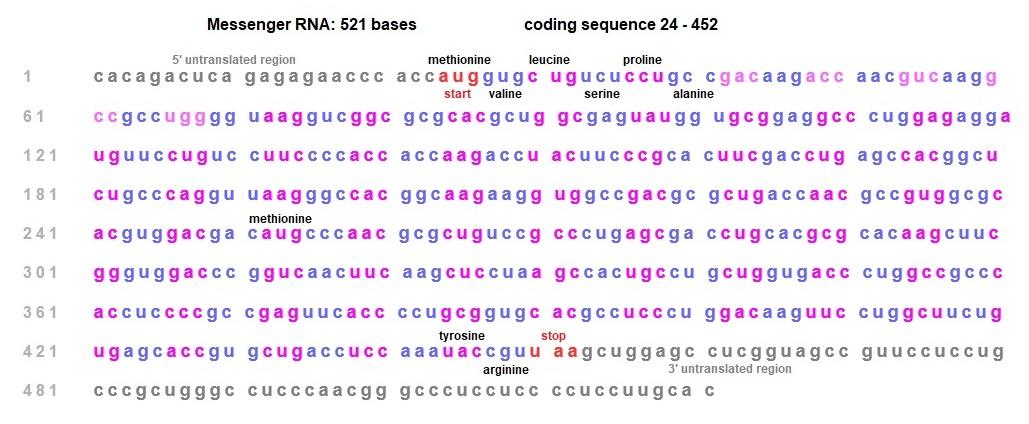

source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/3859549

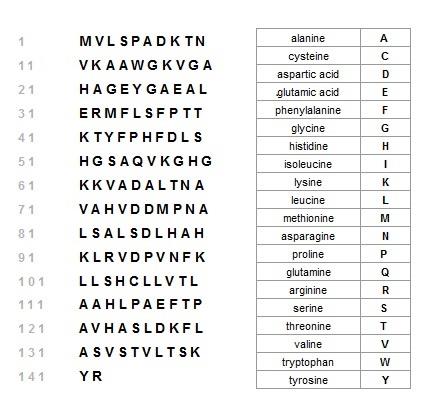

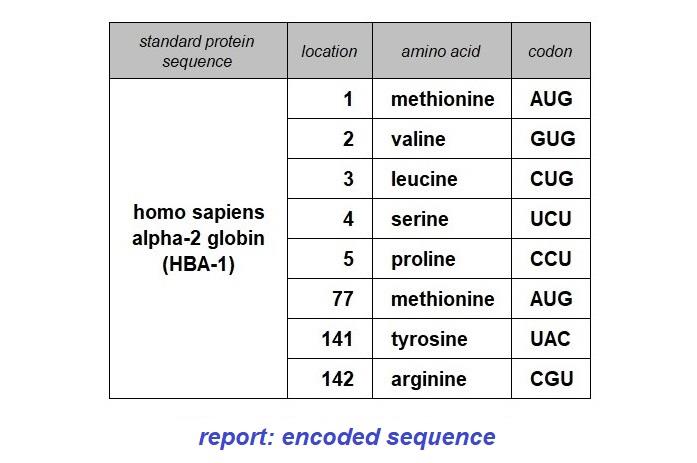

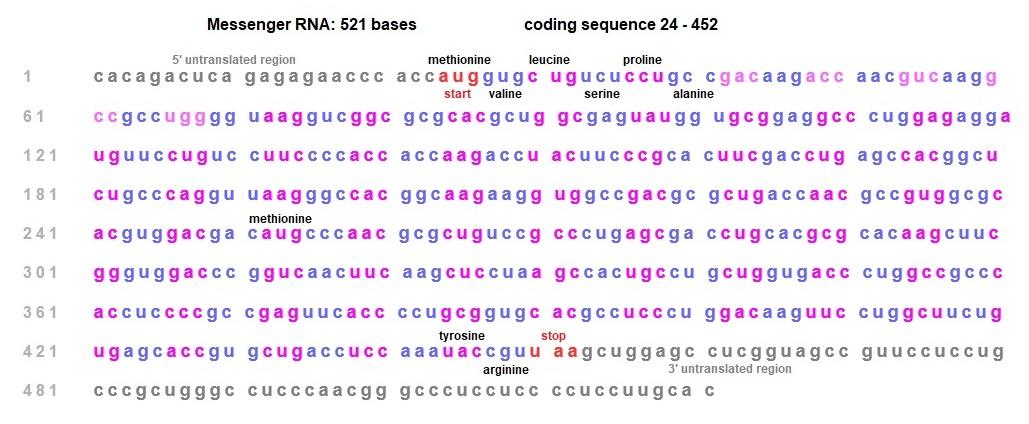

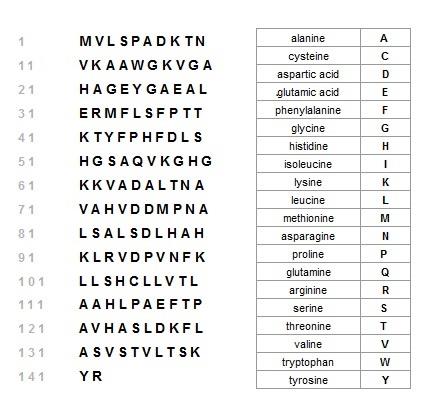

In the sequence below, I have greyed-out the initial and final strings of bases that comprise the 5' and 3' untranslated regions (non-coding). The sequence of 142 codons in the coding sequence starts with the AUG codon ( both a start codon and one that codes for methionine), and the chain of amino acids terminates when the ribosome reaches the UAA codon. The translation of codons to amino acids for the sequence is also shown further below using a single letter to represent each of the twenty amino acids that may be coded for in the standard genetic code. The alternate convention is employed on the source page provided above.

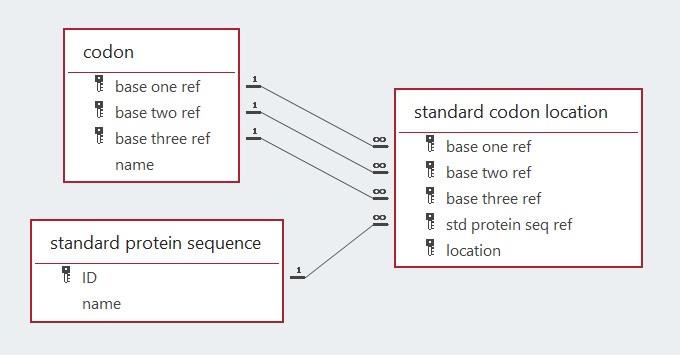

The table above records some of the locations of the codons for the protein product of the HBA1

gene. Although the amino acid reference is not present, the amino acid can be identified via the codon table followed by the standard amino acid codon table. The table below is a report of the codon sequence with the corresponding amino acid sequence also provided, a more human-friendly version.

That covers the remit of this model of the encoding of standard protein sequences in nucleic acids.

The transcription and translation of nucleic acids to protein sequences are, in my opinion, staggeringly wondrous phenomena and that they now seem somewhat explicable to humans is a cause for celebration with the finest wines available to humanity.

It should be borne in mind that the data model of the encoding of protein sequences discussed here has not been reviewed by anyone other than the author.

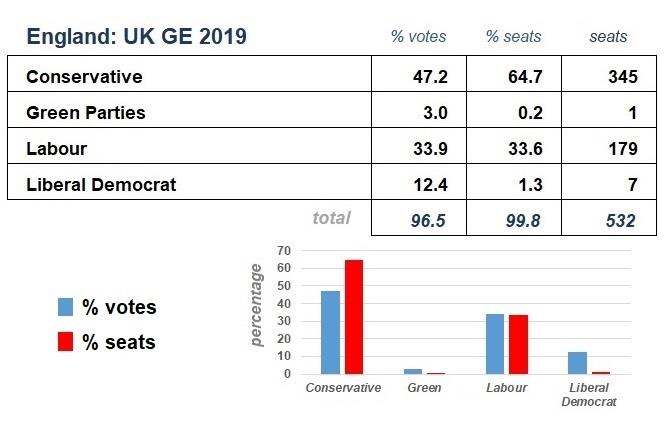

Chapter 11 – UK 2019 Electoral Data

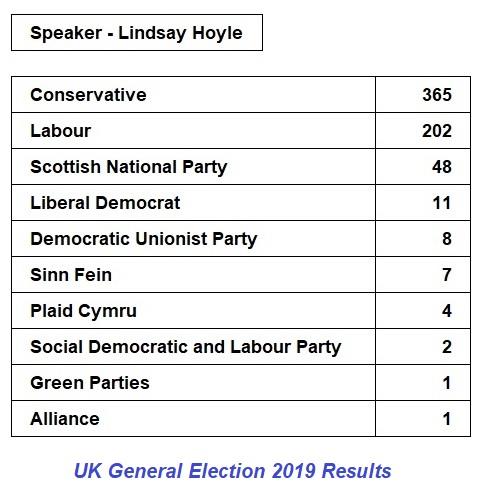

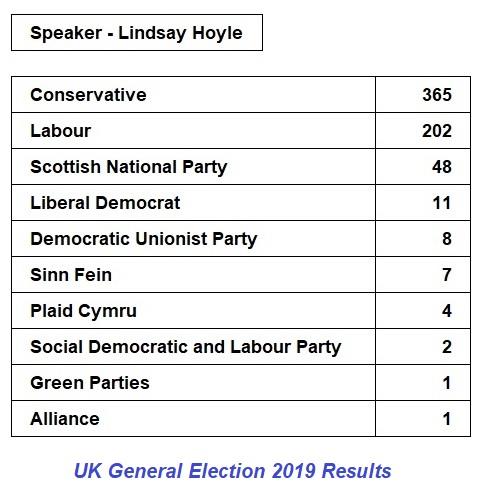

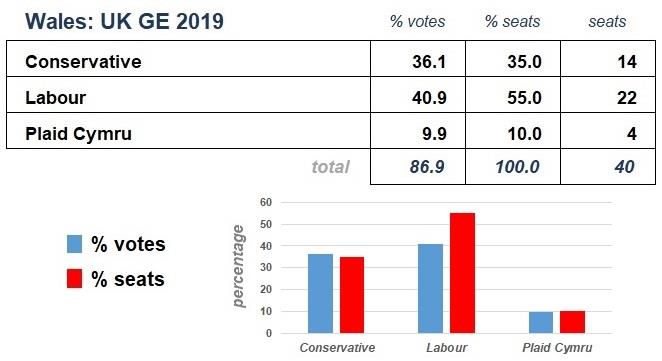

The databases discussed up to this point were populated with raw data, e.g., recording the goals scored and the sequence of protein bases in nucleic acids. This chapter will use derived data to summarise the UK’s December 2019 General Election (GE) results, i.e., the results of 650

constituencies to see if it is an accurate reflection of the electorate’s votes for the UK’s political parties. When using derived data, an ability to verify their accuracy is a critical consideration. This discussion presumes that the House of Commons (HoC) Library is a reliable source of derived data about the results of UK parliamentary elections. What does engender confidence in the data is the fact the HoC Library also provides the raw data that were aggregated to obtain the derived data used in the election report. The data used are from this House of Commons Library Briefing Paper.

The four countries of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) hold general elections periodically to simultaneously elect Members of Parliament (MP) to the HoC in 650

single-member constituencies, The voting system used is called First Past the Post (FPTP) and requires the electorate to choose a single candidate from those standing. The winner is the candidate who obtains a plurality of the valid votes cast in a constituency. Some political parties in the UK field candidates in just one country e.g., the Scottish National Party and Sinn Fein, and some in more than one country e.g., the Conservatives and Labour.

At the 2019 GE, England had 533 seats, Scotland 59, Wales 40, and Northern Ireland 18. Of the 3320

candidates in the 2019 GE, the vast majority were affiliated to political parties. None of the 224

independent candidates won a seat. The MP who is the Speaker of the HoC is a special case and is listed separately, regardless of any previous party affiliation. Some parties do not stand a candidate in the Speaker’s constituency at a general election. A candidate can only stand in a single constituency at a UK Parliamentary general election. Of course, things can change after a general election and there will be MPs who may have resigned a party whip, had the whip withdrawn, or defected to another party, in addition to new members joining because of by-elections or an MP taking the Chiltern Hundreds. The current state of the parties can be found at this HoC site,

https://members.parliament.uk/parties/Commons.

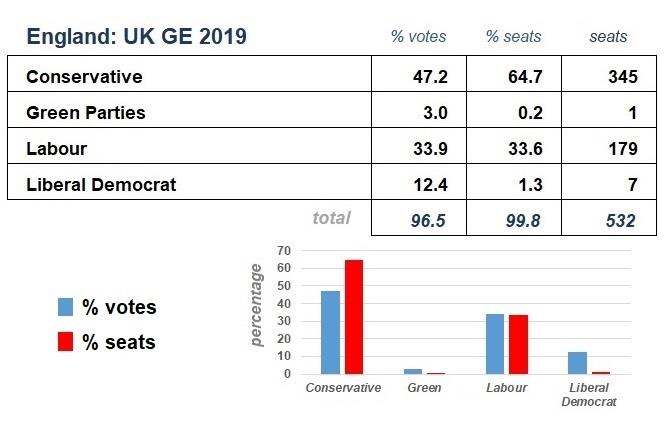

For this exercise, the items of interest are the percentages of the votes each political party amassed (the party result) in each of the four countries and the number of seats won in the House of Commons. For comprehensiveness, all independent, i.e., unaffiliated MPs will also be recorded, in this case, only the Speaker. The efficacy of a parliamentary electoral system is assumed here to be correlated to its ability to ensure that there is minimal discrepancy between the proportion of votes garnered by a political entity and the proportion of its representation in parliament.

There are electoral systems, other than FPTP, collectively termed proportional representation (PR) e.g., party lists or using transferable votes with ranked choices in multi-member constituencies, which have been adopted in many countries to reduce such discrepancy. Unfortunately, even if a PR

electoral system is used as opposed to FPTP, there is academic work (Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem)

showing that it is a Sisyphean task to attempt to get to a perfect correlation between the votes cast and the representation. This theorem however did not discourage many countries from adopting systems that attempt some form of proportional representation to enhance equal representation for votes.

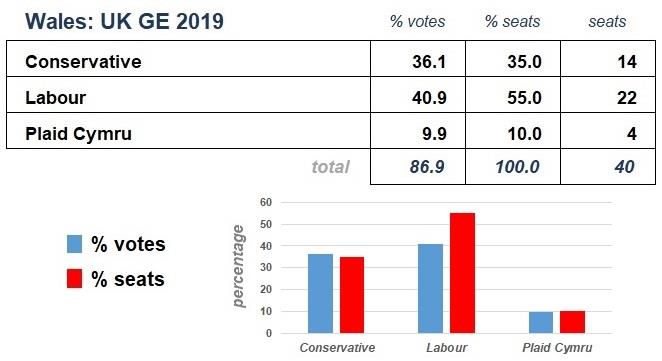

Although the UK parliamentary elections are often reported by country, only the overall result matters.

The table above is an aggregated version of the results of the four separate countries of the UK with the Speaker’s seat excluded. The Conservatives, with a clear majority, went on to form the government. The tables below have disaggregated the information above and assigned the percentage of seats and of votes by country. They show that the parties with the largest share of the seats in each country have achieved that with a percentage of the votes that is lower than the percentage of seats. The Speaker’s constituency, Chorley, is an English constituency and that is why the total of English seats do not sum to a 100%.

All the valid votes have not been accounted for in the following statistics because the votes for parties or individuals who did not gain a seat have been excluded. The HoC Library Briefing Paper and the associated detailed constituency data mentioned earlier do provide information about the unsuccessful parties and independents.

Before coming to any conclusions about UK politics based on the information above, you should make sure that you are satisfied with the provenance of the data.

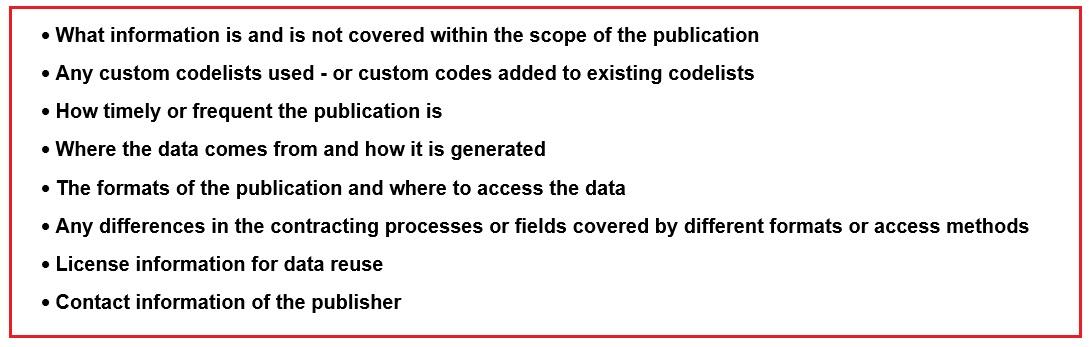

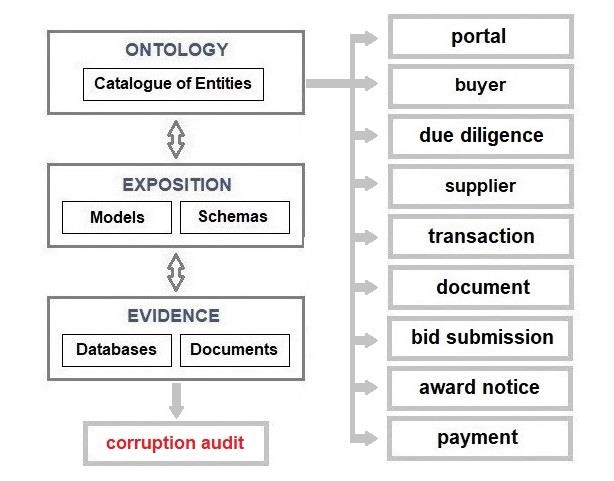

Chapter 12 – Open Contracting Data Standard

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the use of an international data standard. The government of the United Kingdom is committed to publishing public procurement contracts using the Open

Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) to, inter alia, enable members of the public to search for, download, and analyse data about public procurement transactions. The government’s public

procurement policy is published online. The policy materials include the legal framework that buttresses the policy (e.g. the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 (PCR 2015)), handbooks and other guidance, amendments or changes to the policy.

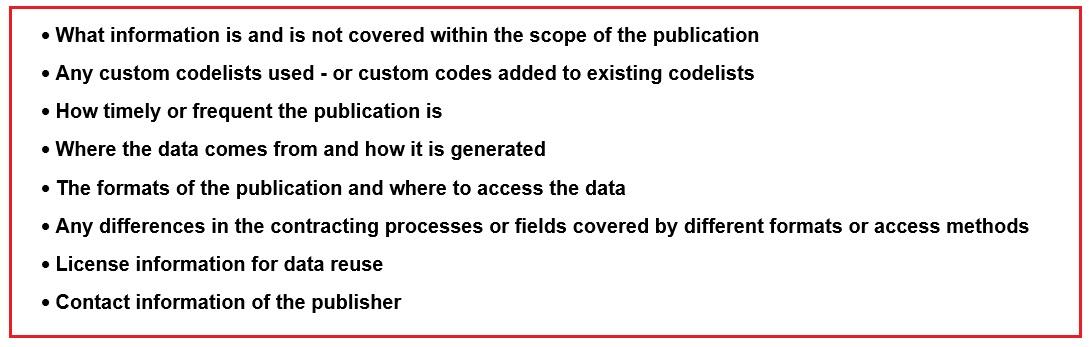

In the interests of transparency, the Open Contracting Partnership (OCP) says, “… a publication

policy is an essential data guide for users. Each OCDS publisher ought to have a publication policy

,,,”:

According to the OCDS, there are broadly four mutually exclusive transaction types available to public sector buyers, the choice being dependent on the relevant legislation and the circumstances of each transaction. There are many factors that can introduce complexity to a procurement transaction. The OCDS lists them as hard cases.

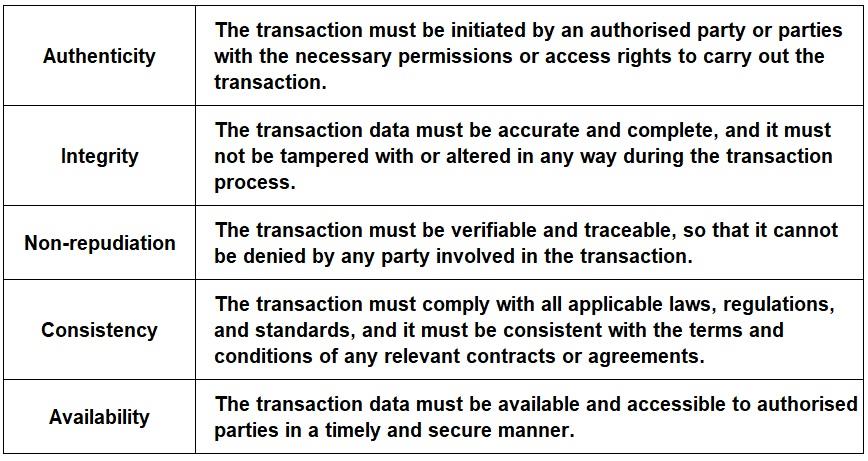

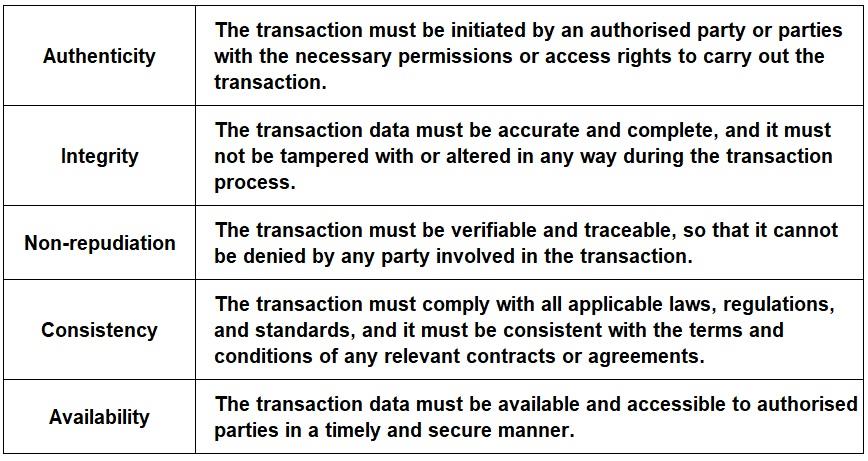

A valid financial transaction typically must satisfy the following criteria, authenticity, integrity, non-repudiation, consistency, and availability.

The fact that contract data are available to the public raises the issue of confidentiality related to some details of the participants’ commercial activities. A balance must be found between what is required to be published in accordance with the OCDS transparency imperatives and the need for confidentiality.

In 2018 the Information Commissioner’s Office published a report assessing the transparency gap in

public procurement.

There are separate public contracting portals for England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. An OCDS compliant public procurement portal must have an identifier assigned by the OCP called the

ocid. The ocid for England’s electronic government procurement portal, Contracts Finder, is ocds-b5fd17.

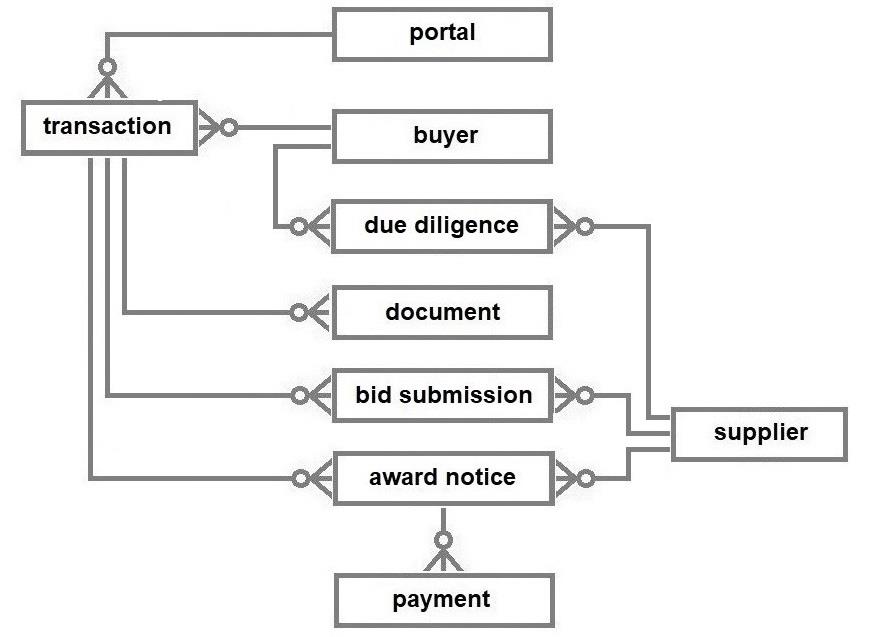

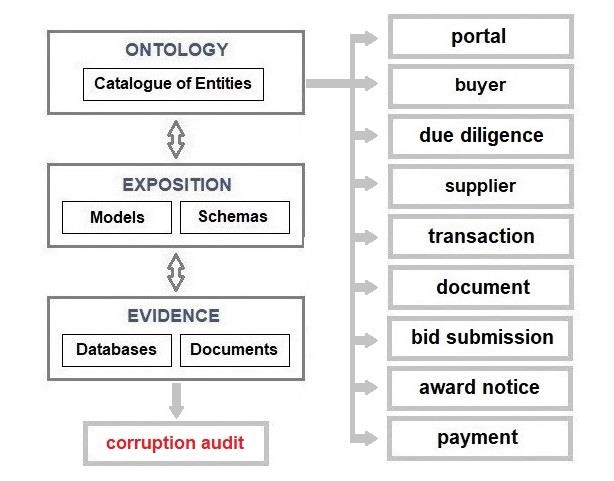

This narrative will focus on the processes and documents associated with a transaction that allow members of the public to satisfy themselves as to the governance of that transaction, e.g., all transactions must have the known or declared conflicts of interests documented and published. The OCDS lists “beneficial ownership information” as a possible cause of a hard case.

Buyers publish their requirements on a public sector procurement portal, e.g., Public Contracts

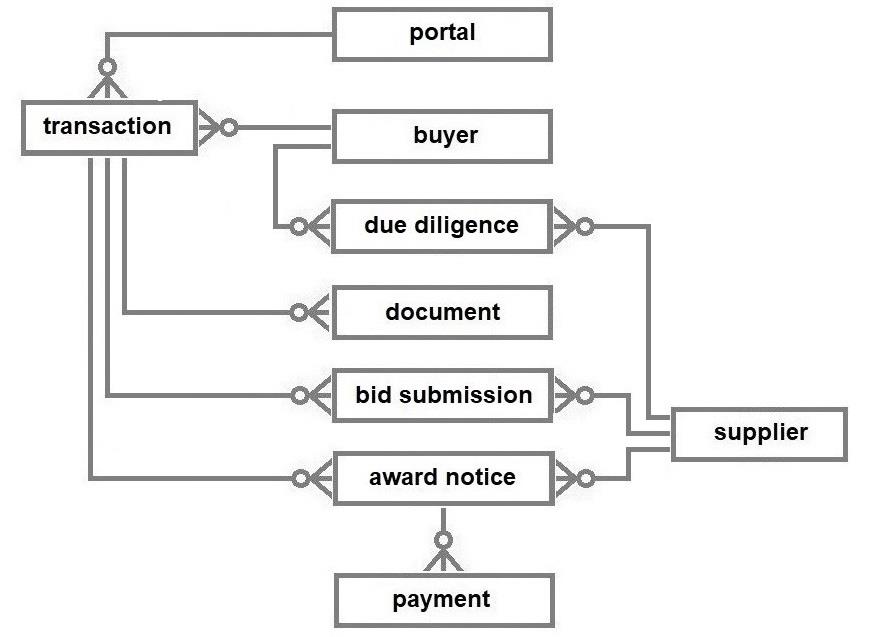

Scotland, and suppliers then bid for contracts to meet those requirements in a tender process. The next stage is the receipt and evaluation of bids followed by the award of contracts to the successful bidder(s). It is also likely that most high-value public procurement transactions will have only preceded after due diligence was conducted on prospective suppliers and those findings documented for the benefit of auditors. In exceptional circumstances a buyer may award a contract without competition.

The denouement is the delivery of the procured items and payments in accordance with the provisions of the contract(s).

When a tender is not open to all suppliers, e.g., the procurement of some types of military equipment or personal protective equipment (PPE) during a public health emergency, there should be a justification posted by the buyer explaining why all or some competition has been dispensed with. The data made available should be sufficient to enable a member of the public to exercise their judgement as to the integrity and efficacy of a transaction, e.g., whether the lack of tendering is reasonable or should be further investigated.

The four OCDS method codes below define the four methods that can be used to conduct a public procurement transaction. The OCDS allows for extensions and amendments to these codes to meet local requirements but does impose rules on how changes are applied. In the case of the method code below, all extensions can only be subsets of the four types shown. The OCDS terms this a

closed codelist. In England’s Contracts Finder, the direct method below is categorised as “other.”

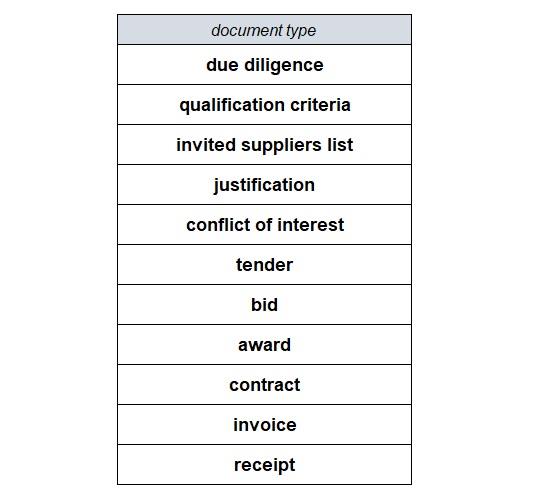

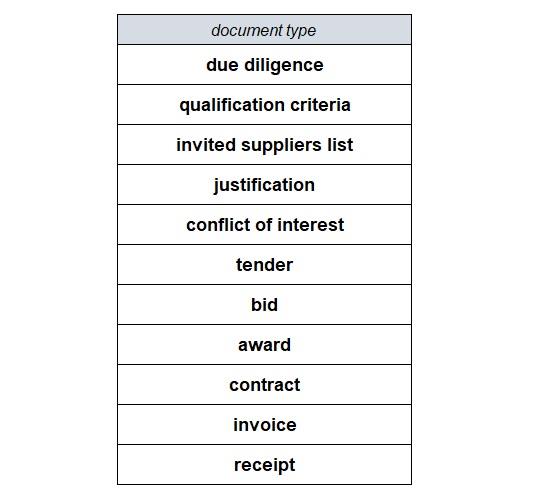

There are many functions supported by the OCDS that will not be discussed here unless they impinge directly on the governance of a transaction. There are many codelists that are critical for the logistics of managing a transaction (e.g., milestone type) and to understand industrial trends, (e.g., the Common Procurement Vocabulary (CPV) for product classification) but they will not feature in this discussion. The OCDS document type codelist is an open codelist and the administrators of the portal are responsible for ensuring that the buyers have the option of posting the different types of documents that facilitate and evidence the procurement process locally.

Buyers, upon initiating a transaction, must publish the documents in accordance with the timescales stipulated in the relevant regulations or guidelines. The combination of the method code of a transaction and the document type codes will allow an auditor to check if the appropriate documentation has been published, e.g., a direct award should have a justification document published in addition to the specification of the deliverables and payment schedules as agreed between the buyer and the supplier in the contract. It would be reasonable to expect the publication of the outcome of the due diligence on a supplier, especially with a direct award, in the interests of transparency and the avoidance of the stench of corruption.

The document types listed above are critical to the process of providing the requisite evidence for auditors. There are, of course, many more document types involved in the management of the processes supported by the OCDS, but they are not required for this exercise. While the majority of document types above are common to all tendered procurement processes, the invited suppliers list, due diligence documentation, qualification criteria, the justification, and the conflicts of interest are requirements for public procurement transparency.

It is assumed in this explanation that the public are primarily interested in what was procured from the public purse and how much was paid for it. Whether an auditor is able to ascertain if a transaction was a fair transaction and that the public had obtained “value-for-money” will depend on the information published about the transaction on the government’s electronic procurement portal, industry knowledge and any further research the auditor undertakes.

The initiation of a transaction is assumed here to be when a tender notice or, exceptionally, an award notice is published. However, in some jurisdictions, there are regulations that require other events during a public procurement transaction to be documented e.g., in Paraguay, the planning decisions have to be evidenced.

The auditor will need access to any changes made to any published document e.g., to the contracts especially if there are additional charges or if there have been delivery problems. All OCDS compliant solutions must have facilities to publish subsequent amendments to any published data.

This model is my idea of a data model representing the minimum types of data that are sufficient to effectively reach a conclusion as to the integrity of a public procurement transaction, i.e., achieve OCDS compliance. The model does not purport to be representative of any real-world solution. It only discusses those facets of the OCDS that are related to audit facilities and ignores the logistical part of the public procurement process.

The data available on Contracts Finder about the direct award by the Department of Health and Social Care of a contract to Ayanda Capital Limited in 2020 for the supply of PPE will be reviewed next. The reason that this transaction is being analysed is because the government’s transparency

policy, Contracts Finder, and Ayanda all featured in a high court judgement (41-page pdf – e.g., see para. 2, 4, and 31(a)) in February 2021, (Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWHC 346 (Admin)).

Although no individual procurement decision was challenged in the claim brought by the Good Law Project and three opposition MPs, D. Abrahams, C. Lucas, and L. Moran against the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, the claim was about the government’s implementation of its public procurement transparency policies and principles and matters that arose as a result of the public sector procurement activities. In my opinion, this judgement is a useful exegesis of current public procurement policy documentation in the UK.

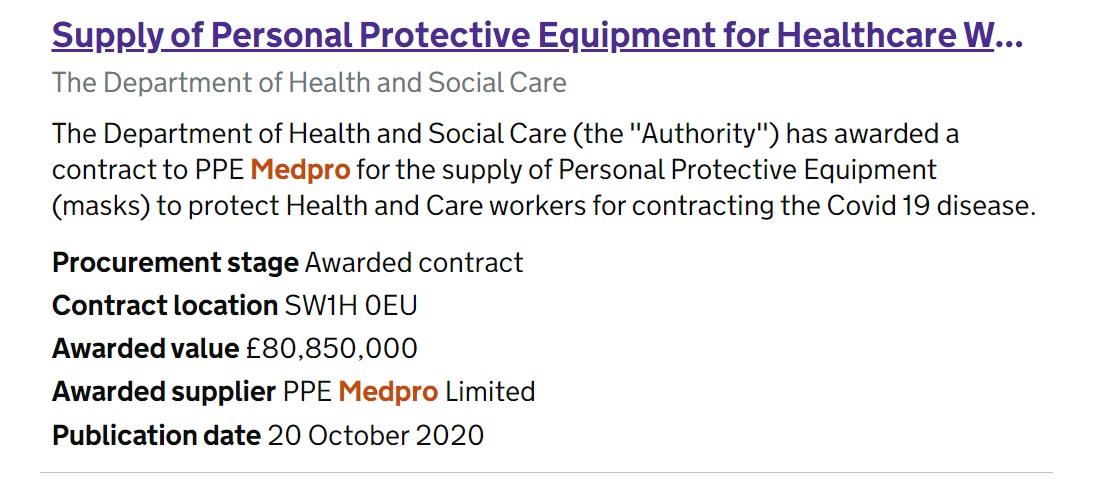

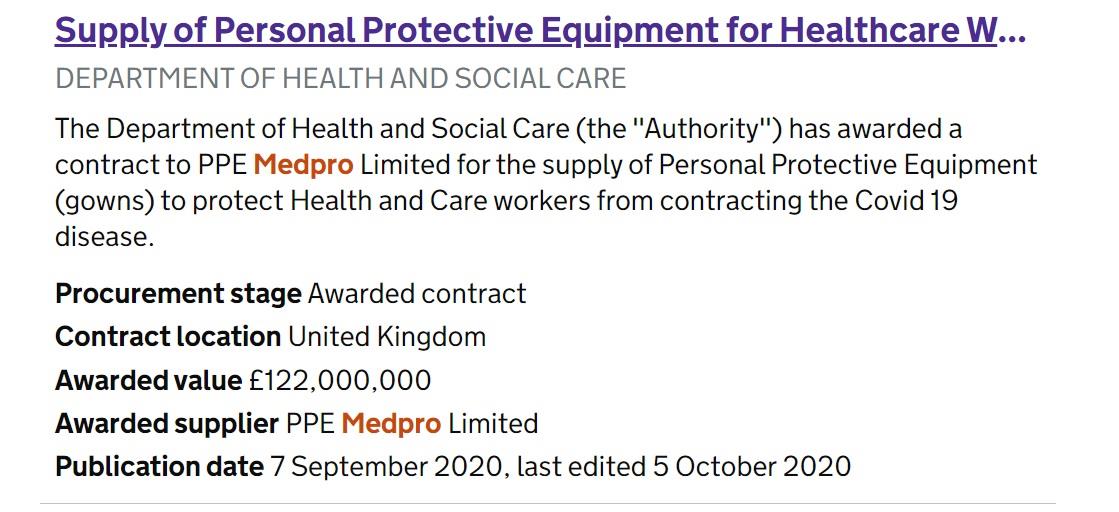

To find the award notice on Contracts Finder, the following search terms were used. The keyword used was “Ayanda” and the procurement stage “awarded contract” was selected. The only result of the search is shown below.

The link to the award notice is embedded in the title of the result. The publication date of the contract award notice implies that the transaction had been initiated sometime before 27 July 2020, as will be confirmed from the information in the Contract Award Notice (CAN - as the award notice is termed in the judgement of Chamberlain J referenced earlier). This CAN was last amended on 4 September 2020 but there are no data as to what was edited. The CAN specifies that the method or procedure type is the equivalent of the OCDS direct method.

The CAN provides links to other resources including two documents, the justification for the lack of competition and the contract. There were no documents related to due diligence or conflicts of interest published on Contracts Finder with respect to this transaction. A link to the specification of the

deliverables, embedded in the contract document, was not working (“not found” was the response) on 10 August 2022 and 17 August 2022. There were no documents posted about payment information related to this transaction. Therefore, excluding the missing specifications, the data available in the public domain about this transaction are in three documents, the award notice or CAN, the justification of the absence of competition, and the contract.

The justification for this transaction is a short document (less than 500 words) and it references PCR

2015 Regulation 32(2)c which authorises a no competition award under certain circumstances, The auditor has to decide whether the justification is adequate. The contract is a document (17-page pdf) of three parts: the contract details, the terms, and conditions, and two schedules with some redactions. Again, the auditor has to decide if the information available in the redacted contract was sufficient to arrive at an informed conclusion about the governance of the transaction.

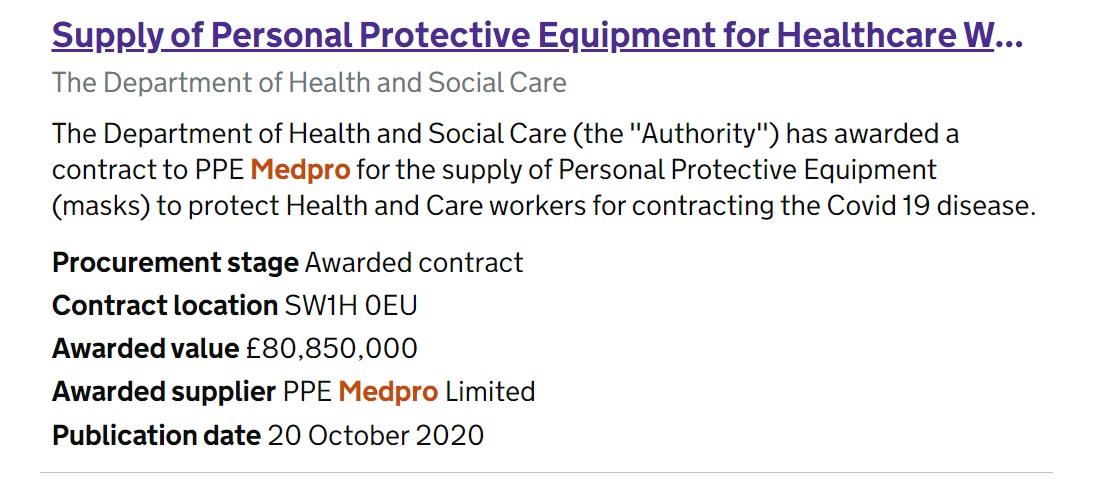

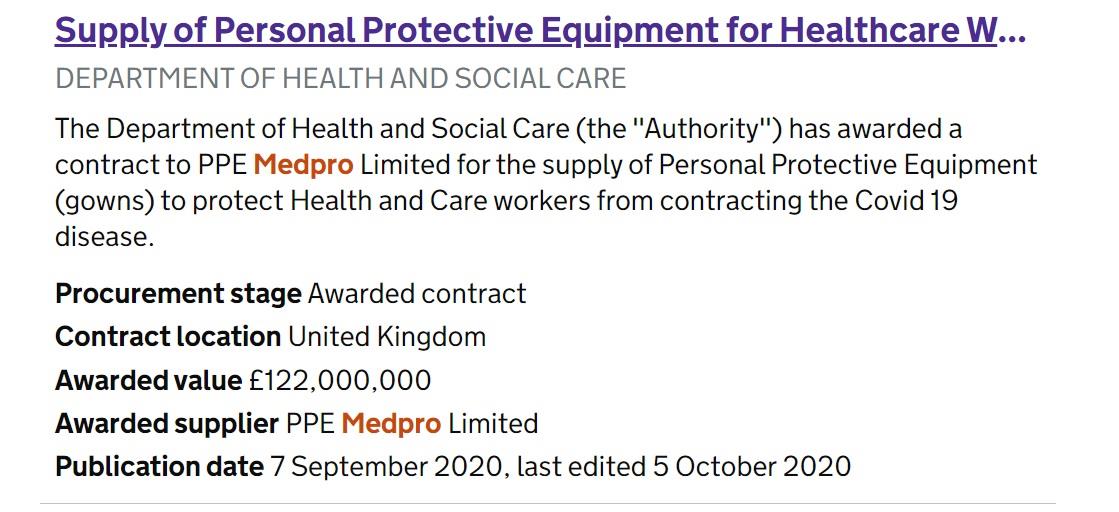

On 1 September 2022, another supplier who was awarded two direct contracts for PPE by the DHSC

was in the news. The search results are shown below. There were no documents posted about either any conflicts of interest or about any payments related to these two transactions - PPE Medpro CAN

1/ PPE Medpro CAN 2.

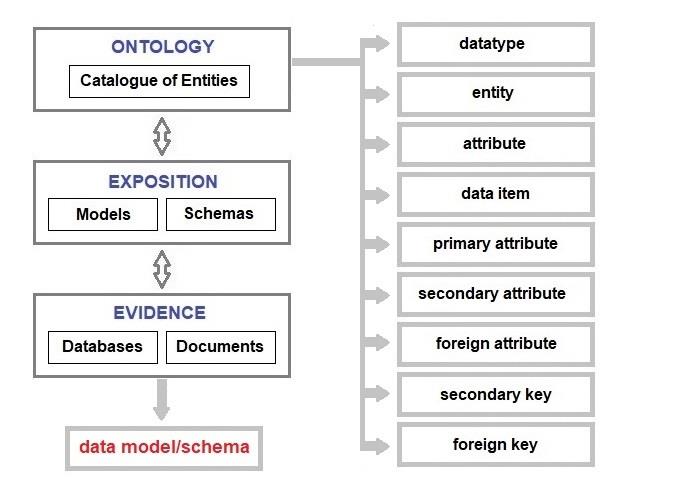

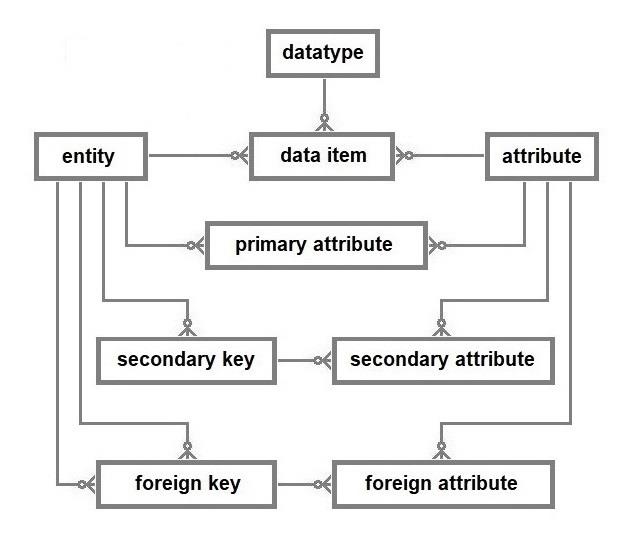

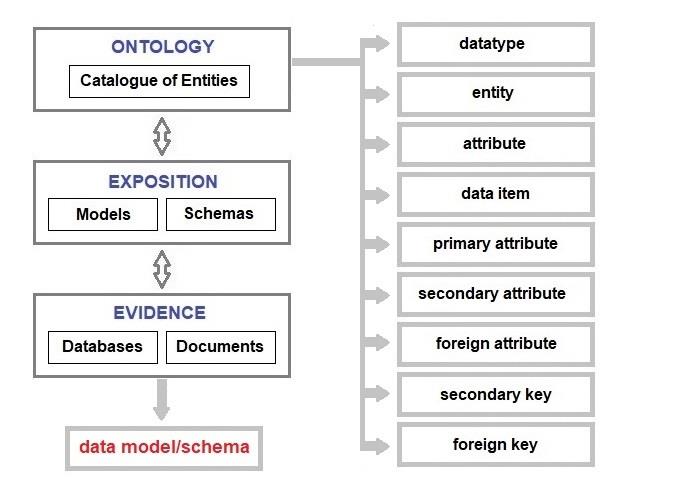

Chapter 13 – Anatomy of a Database

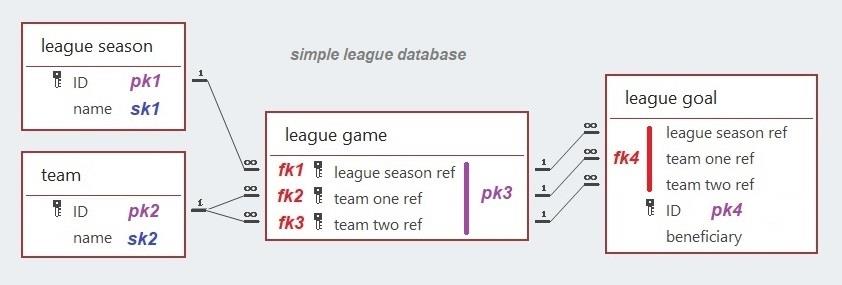

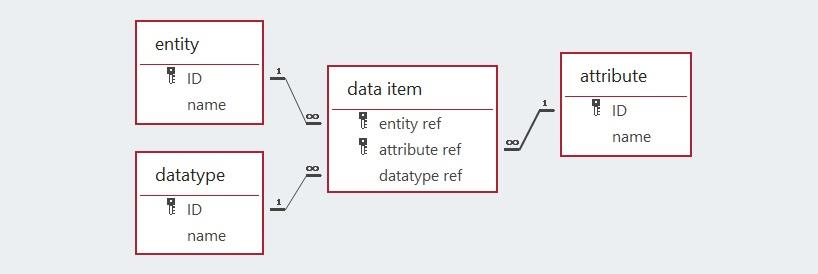

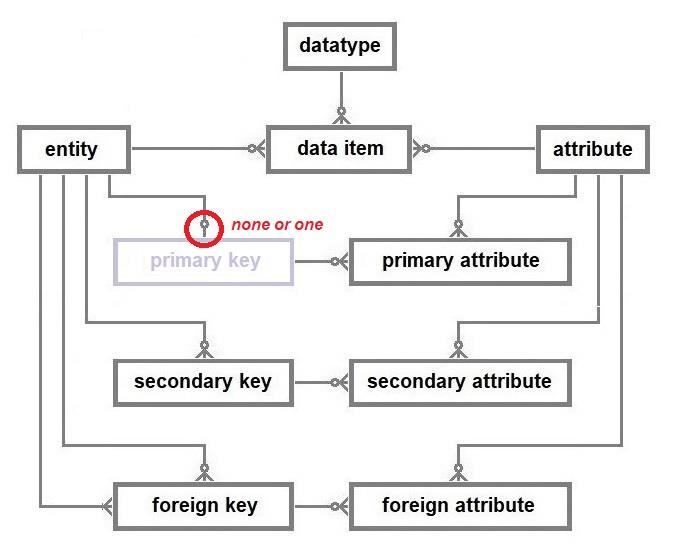

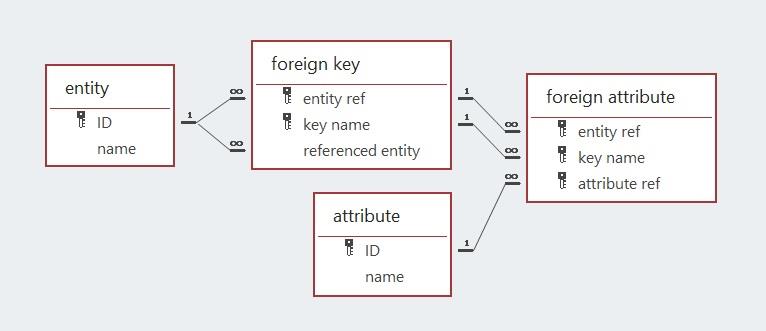

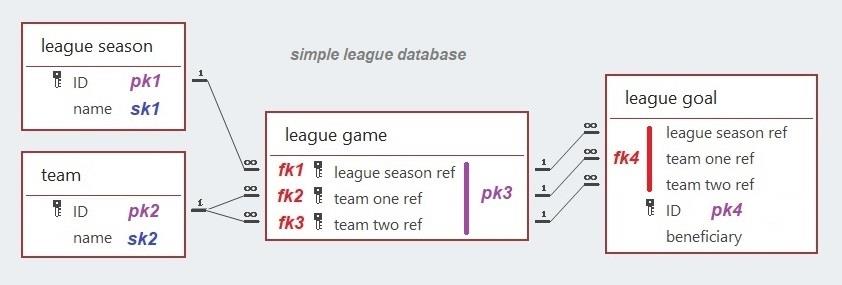

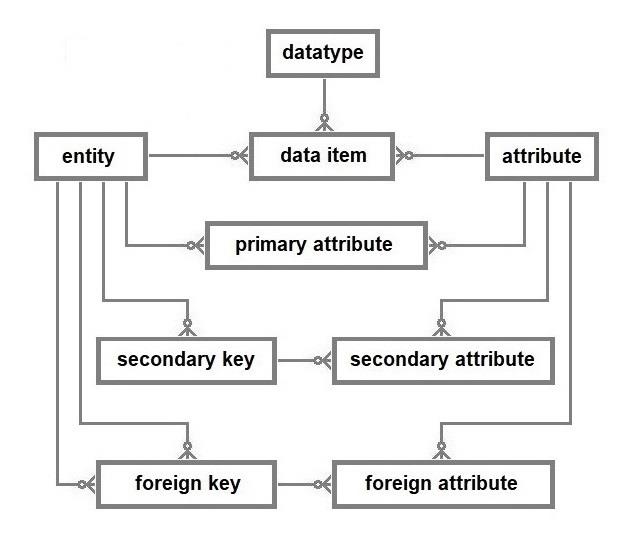

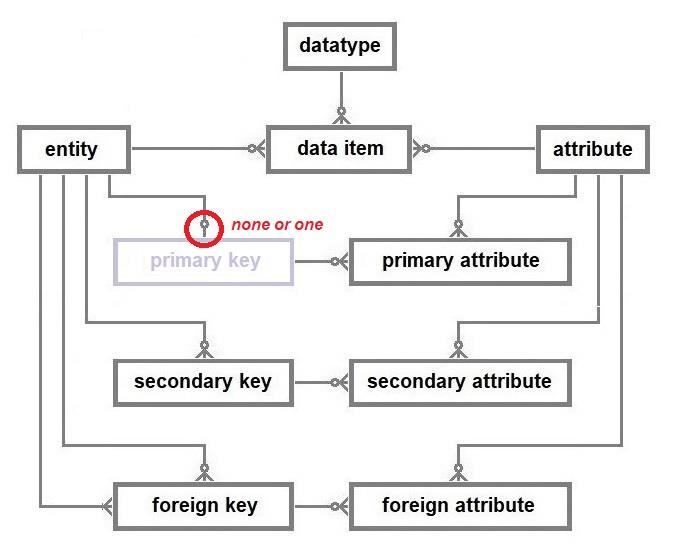

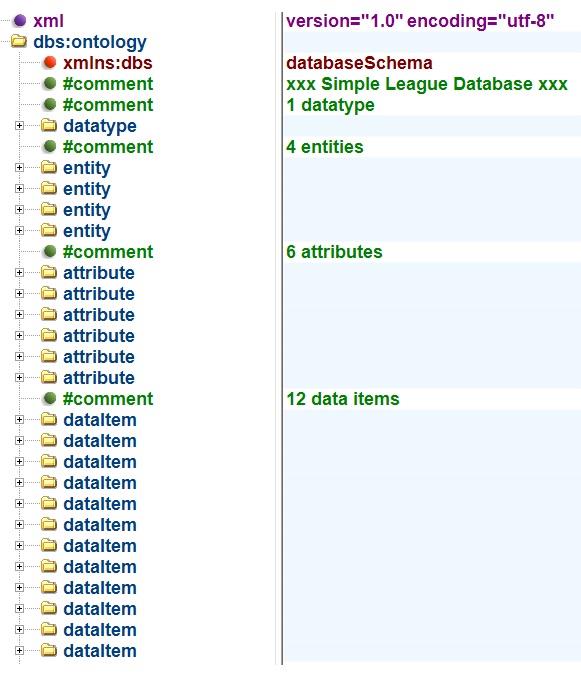

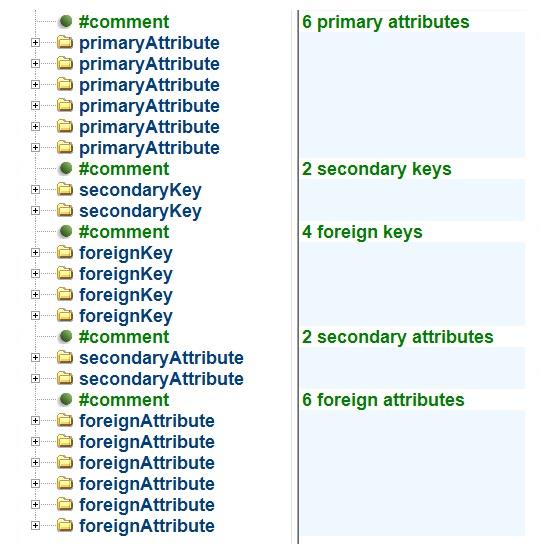

This database model comprises the nine constructs listed above. They are the entities used when designing the databases discussed previously. The simple league database will be deconstructed to explain the database model.

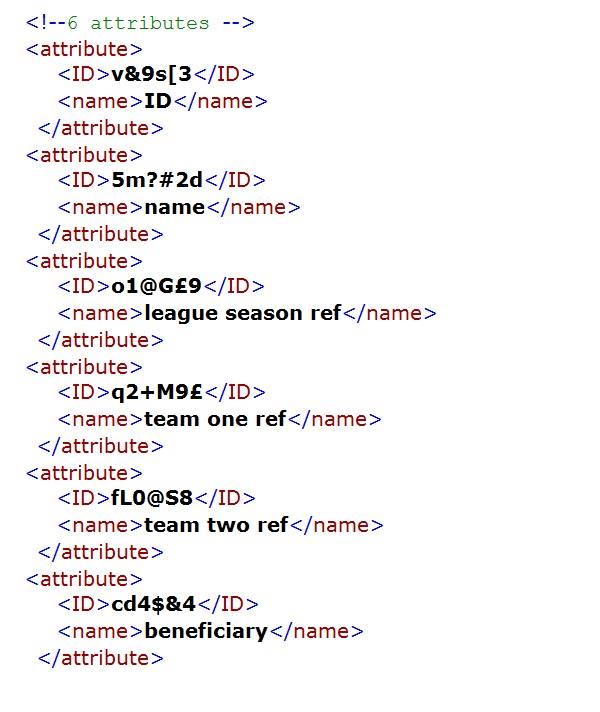

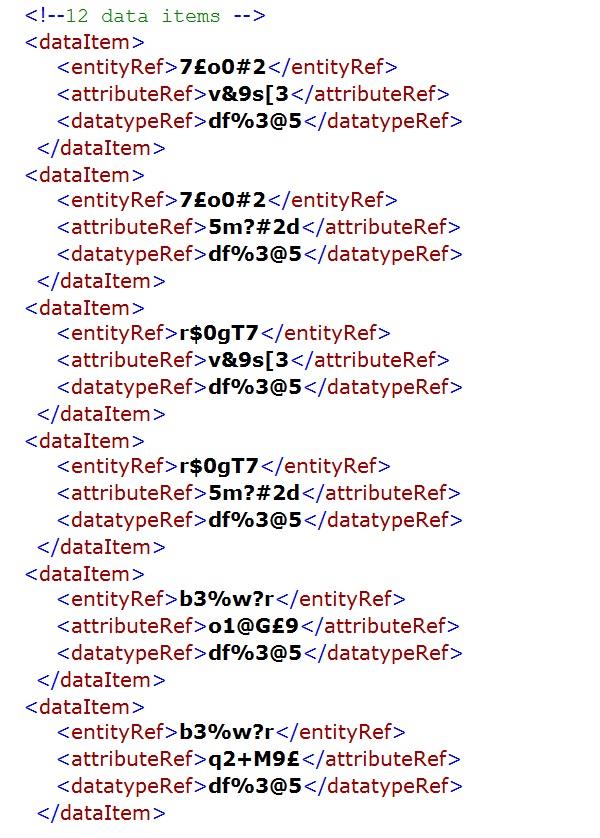

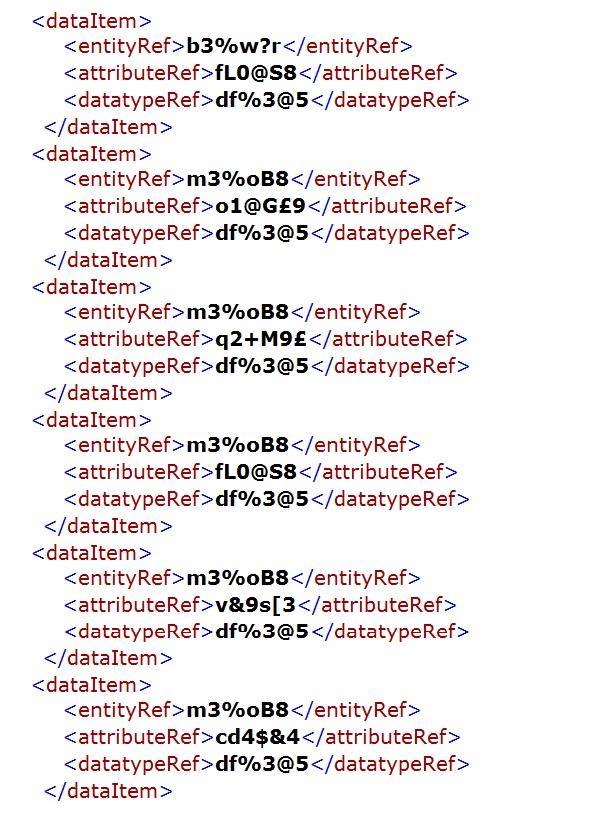

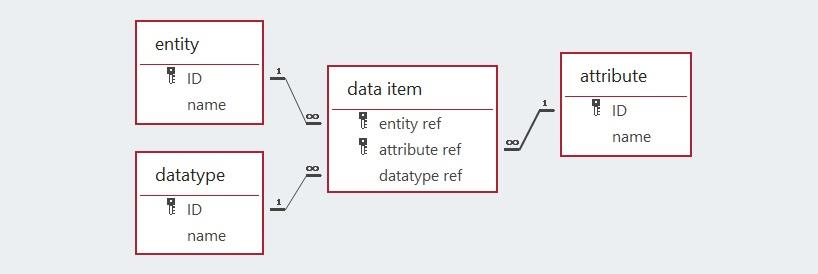

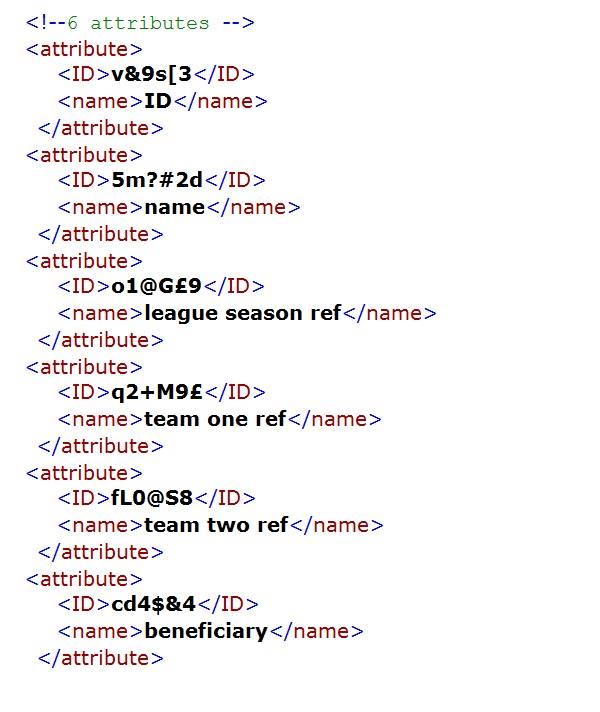

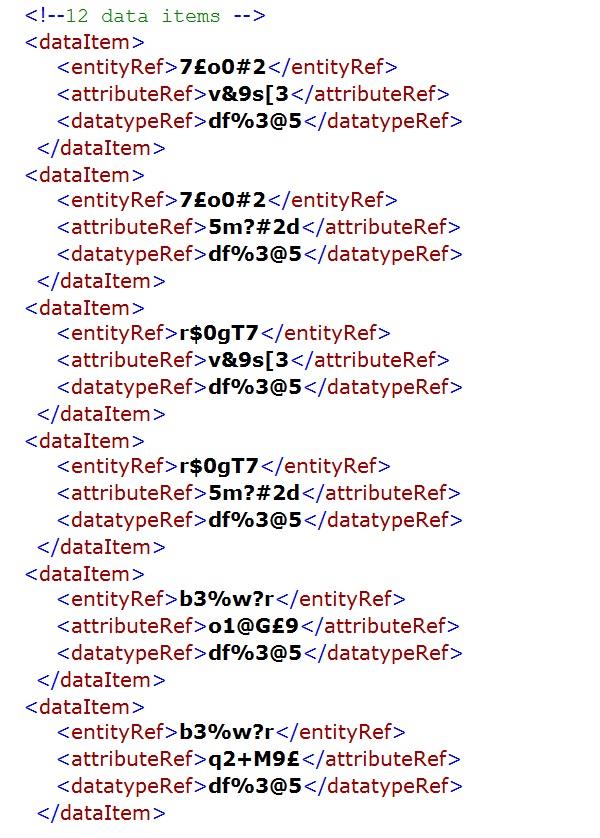

In the simple league database, the only datatype used was the text string and that applies to all twelve data items. The twelve data items are distributed between the four entity types. The beneficiary attribute of the league goal entity type has a specialised restricted string datatype that only provides two options, team one and team two. Unlike the beneficiary attribute, the other five attributes used to specify the data items are common to more than one entity type, e.g., ID and name.

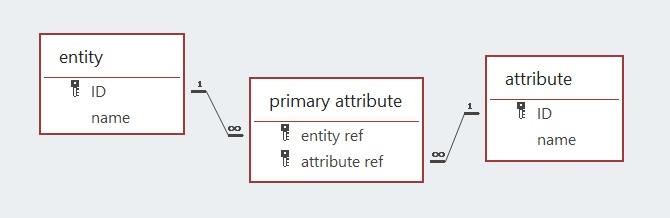

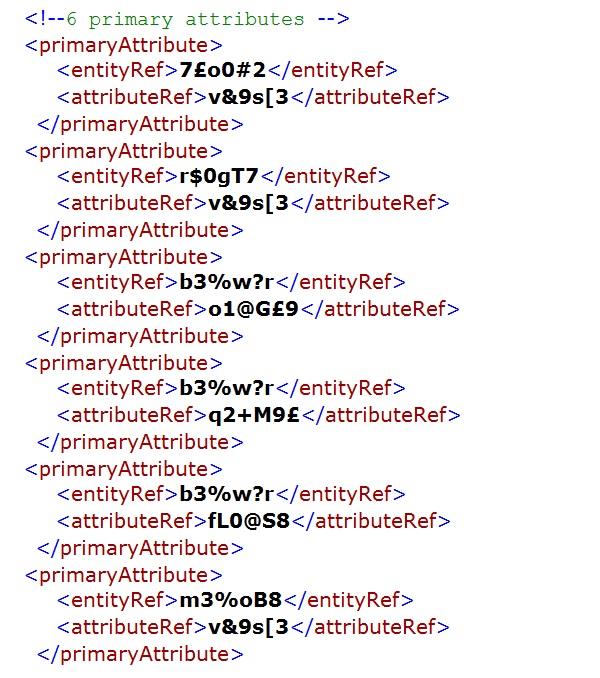

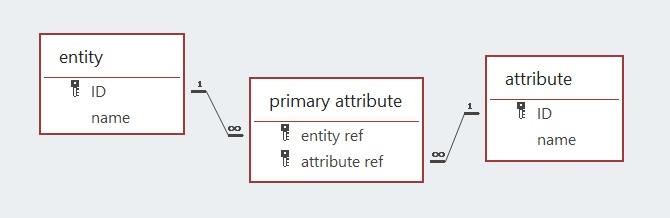

The data model of a database above does not feature a primary key. This is because all primary attributes are linked to an entity and knowing that an entity can only have one primary key allows the existence and composition of the primary key to be deduced from the designated primary attributes.

However, the real world intrudes, necessitating the explicit statement of the primary key’s existence if there is one. Data management systems seem to require evidence that a primary key has been designated. Therefore, to allow the database management system to reference the primary attribute(s), a single unique label is used to signpost the primary attribute(s). As a result of that real world requirement, primary keys have been named in the data models discussed above. MS Access automatically assigns the label “PrimaryKey” to the designated primary attribute(s) of a table. An XML

schema also requires primary keys to be named (see chapter 5).

The data model below therefore includes a ghost primary key, but it is only a sop to real world data management techniques and adds nothing to the understanding of a database’s structure.

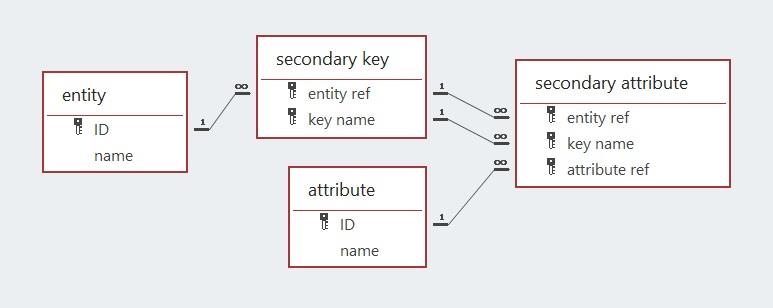

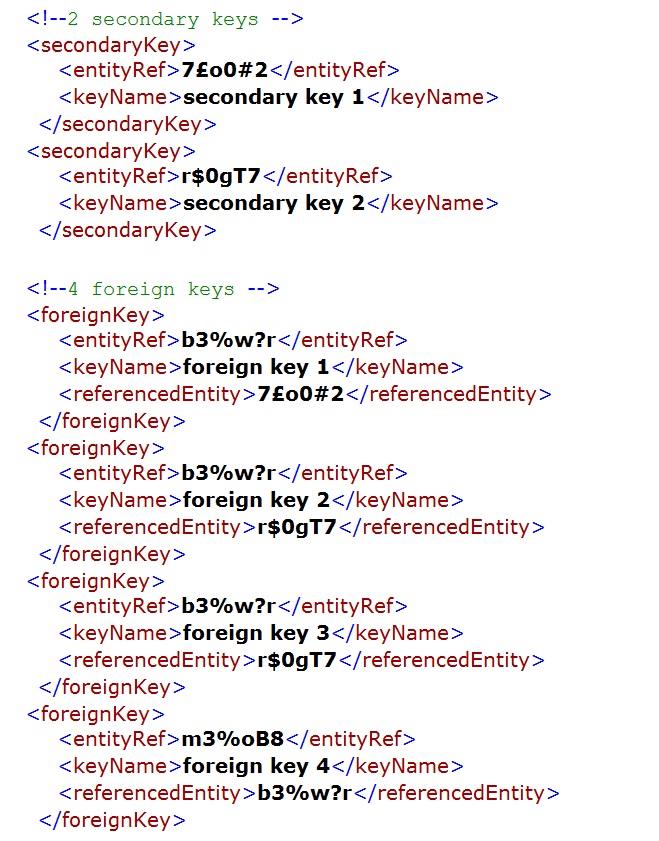

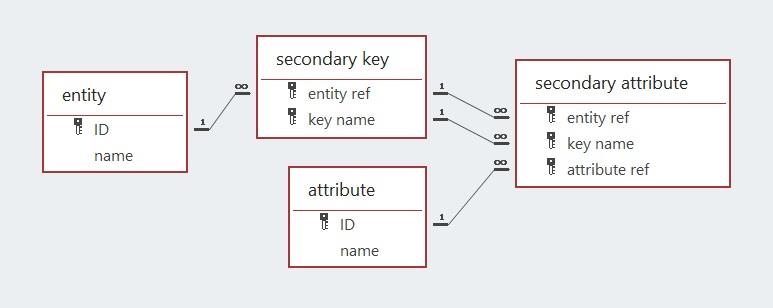

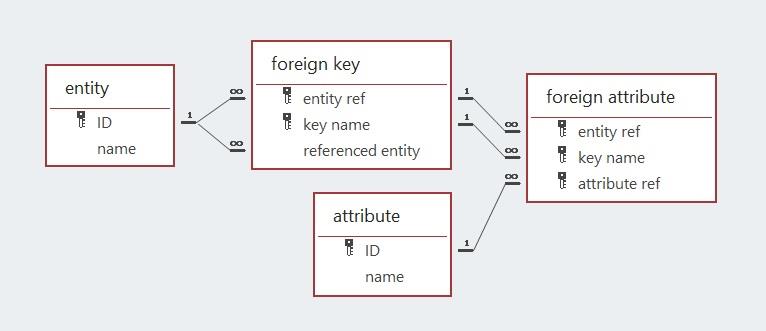

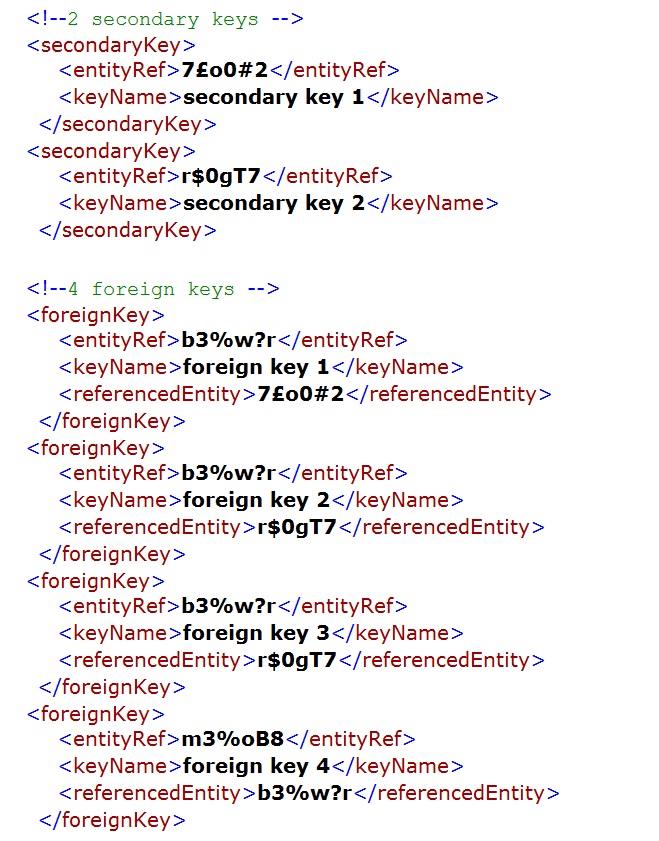

An entity may have multiple secondary and foreign keys. This luxury generates the need to differentiate these keys by giving them unique names. Note that the names of secondary and foreign keys cannot be changed because they are part of multi-attribute primary keys.

The above explanation should be consistent with the design of the databases discussed earlier. My apologies if that is unclear. Well, if it is clear, you should now have an appreciation of how digital databases may be built with the use of three types of keys to structure the data items being collected.

The appendix, unfortunately interminable, is an indulgence on my part and is unlikely to be of any significant use to most readers, but it may help diligent students. It provides an XML document (instance) with the specifications of the simple league database structure and an XML schema for the database model discussed in this chapter. The schema was validated using the Corefilling utility

referenced in Chapter 5,

Appendix – Database Instance and Schema

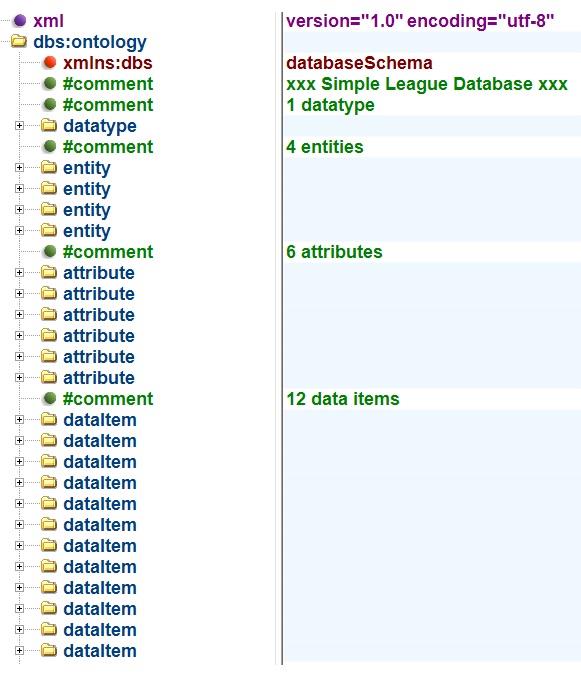

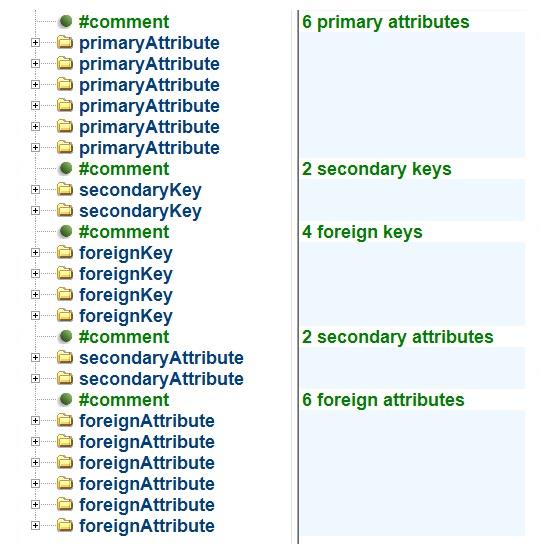

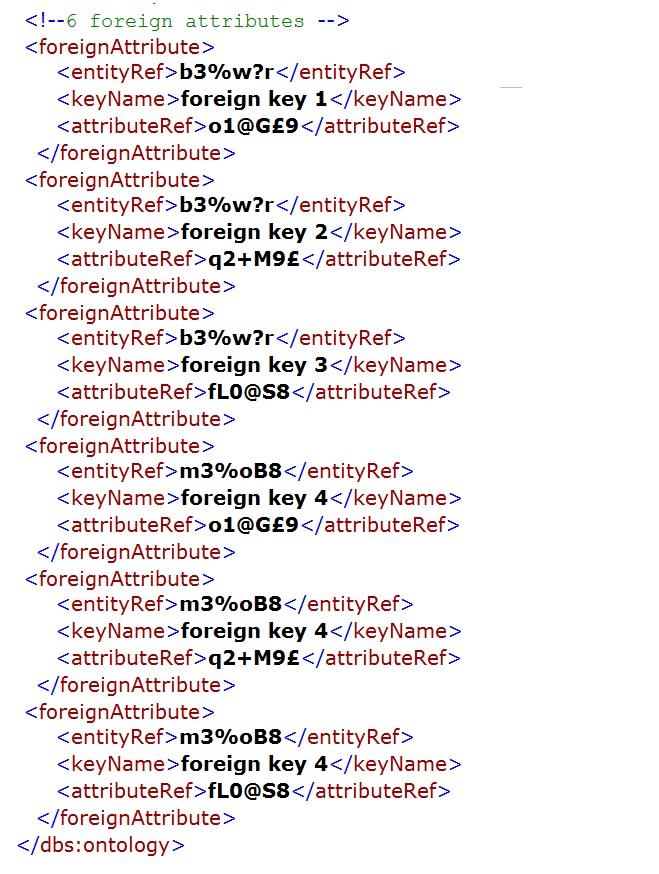

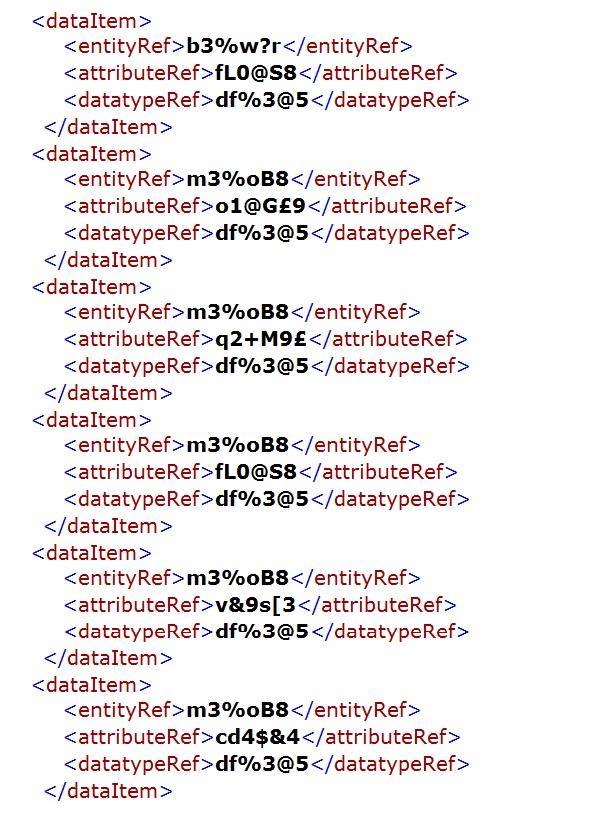

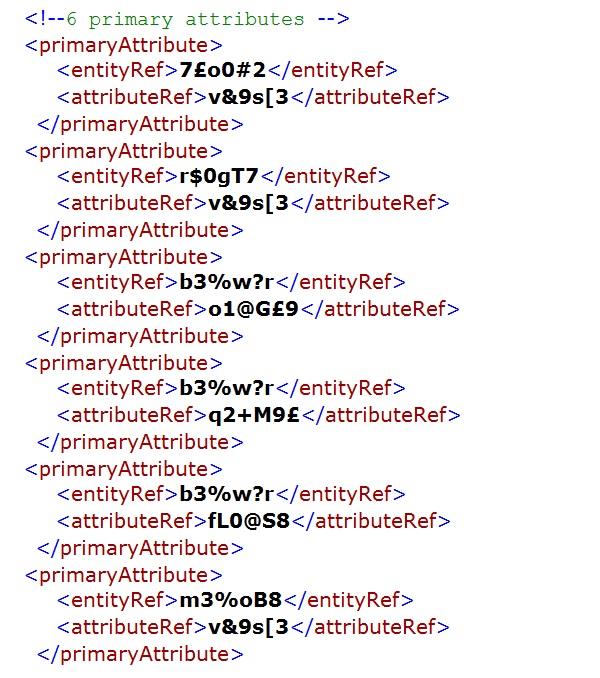

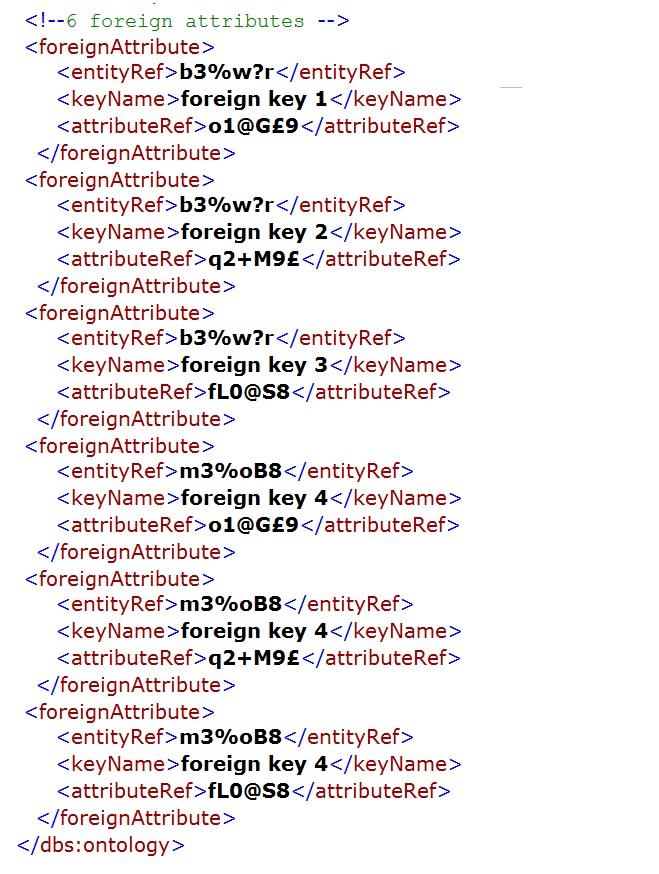

The following XML document is a machine-readable version of the simple league season database structure introduced in Chapter 2.

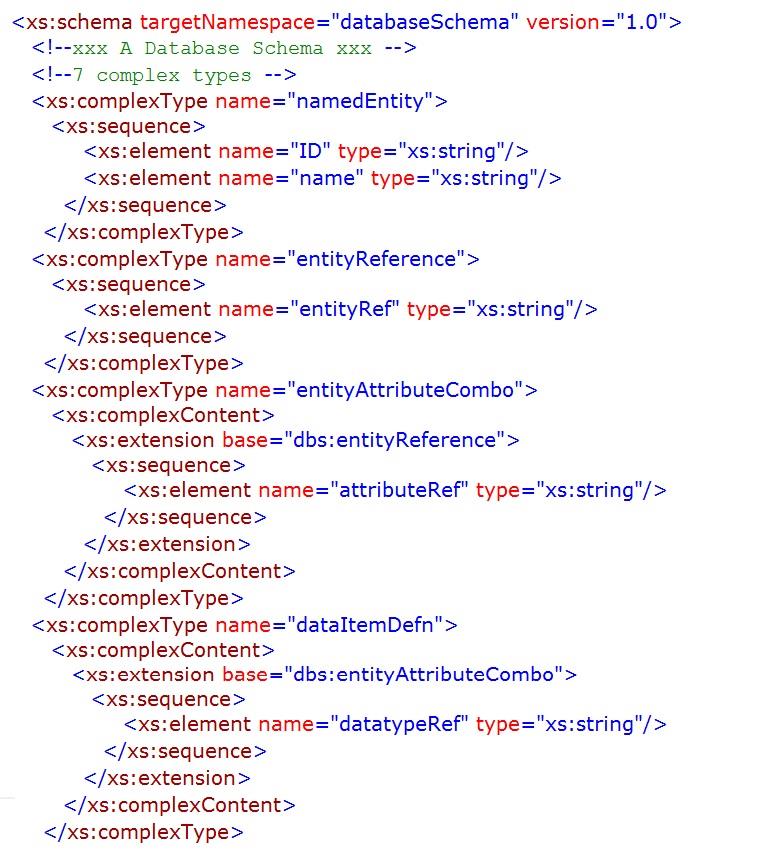

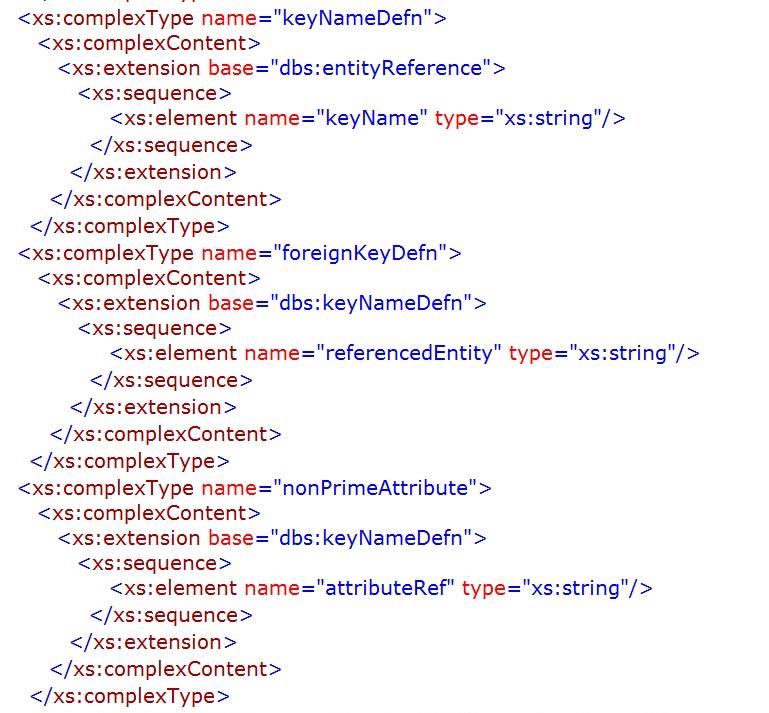

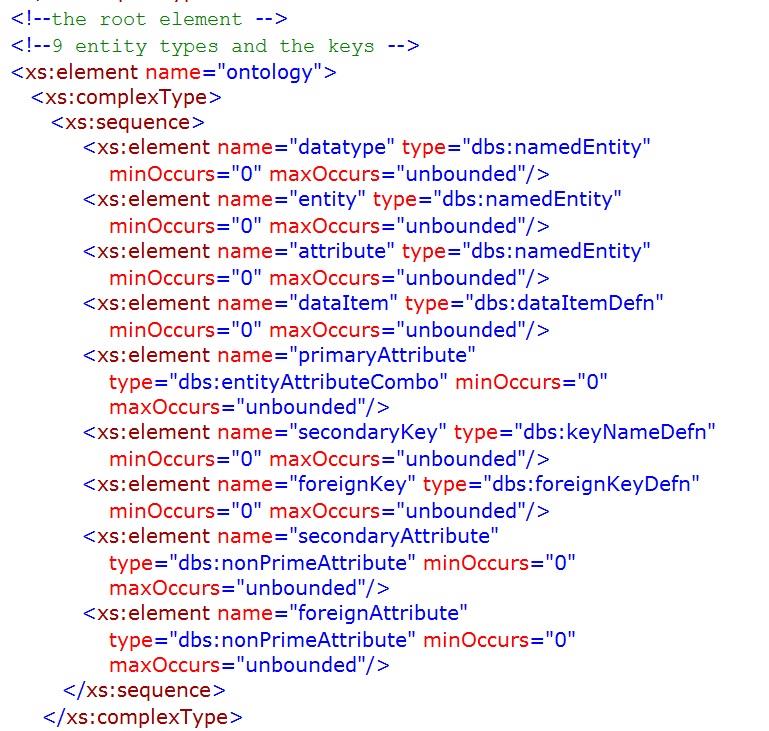

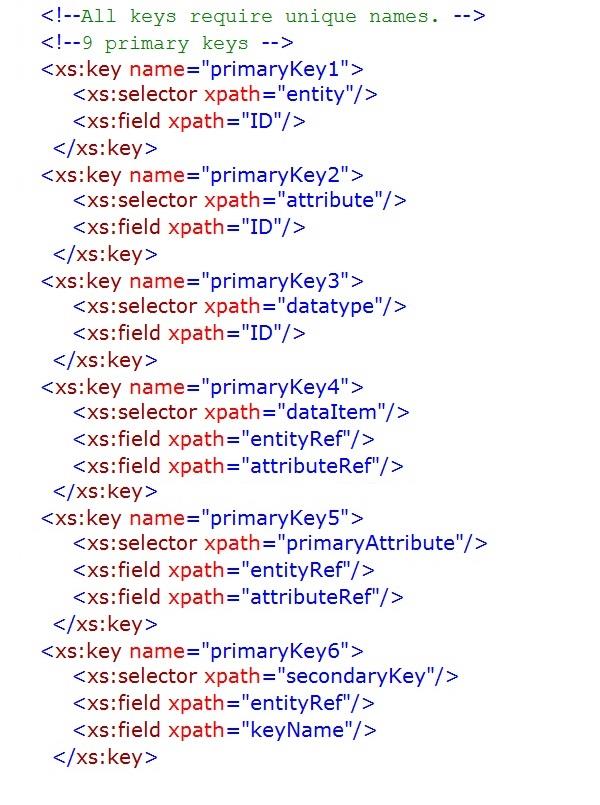

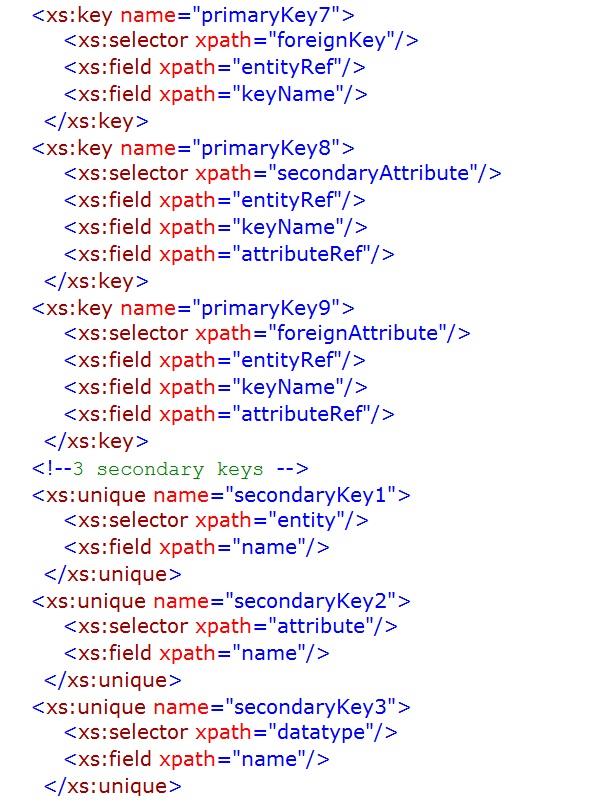

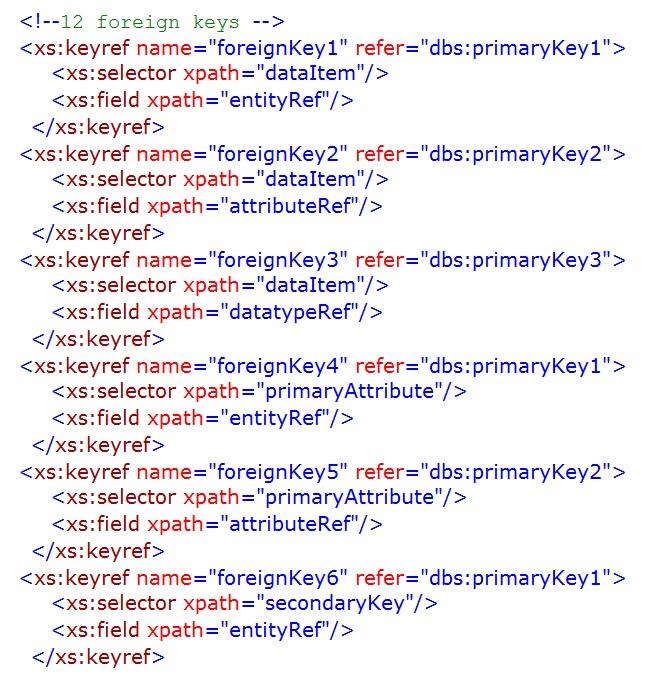

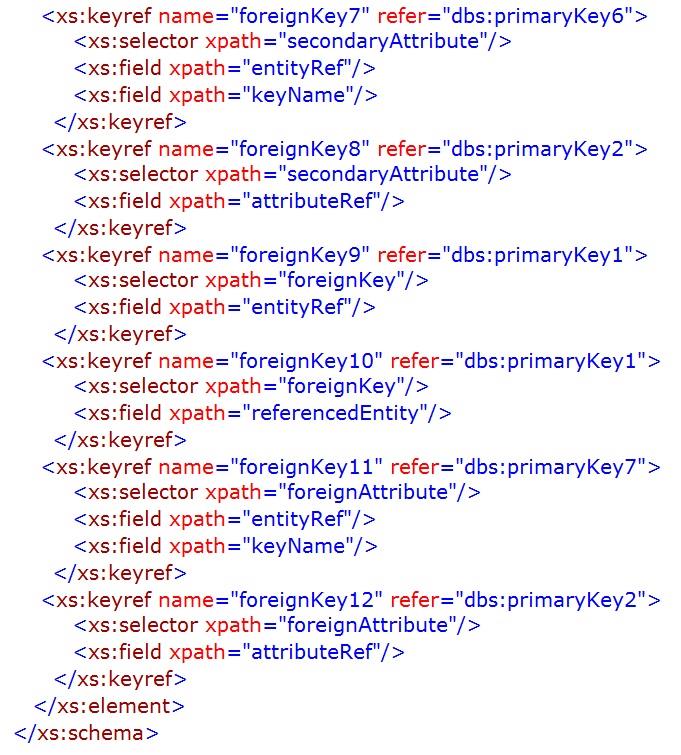

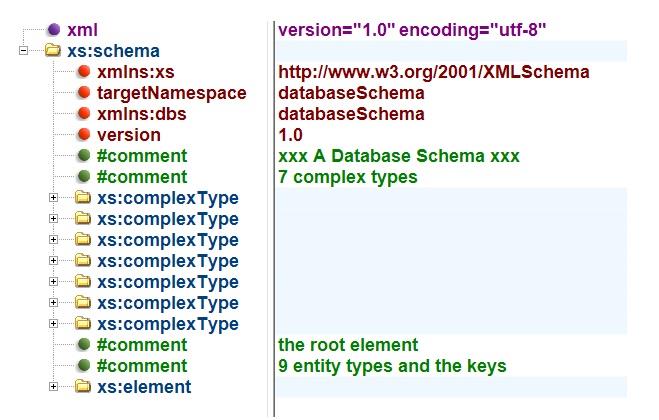

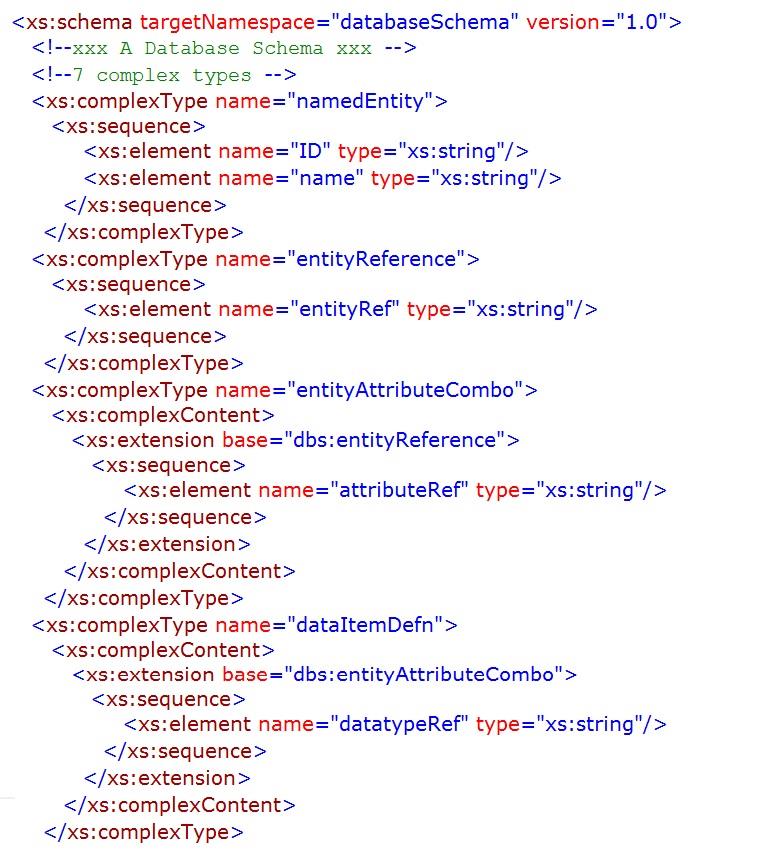

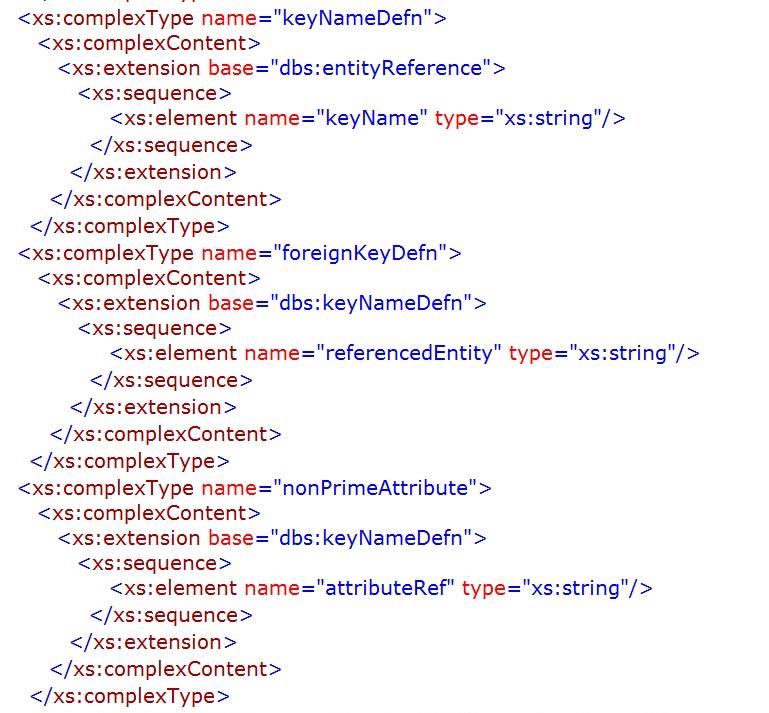

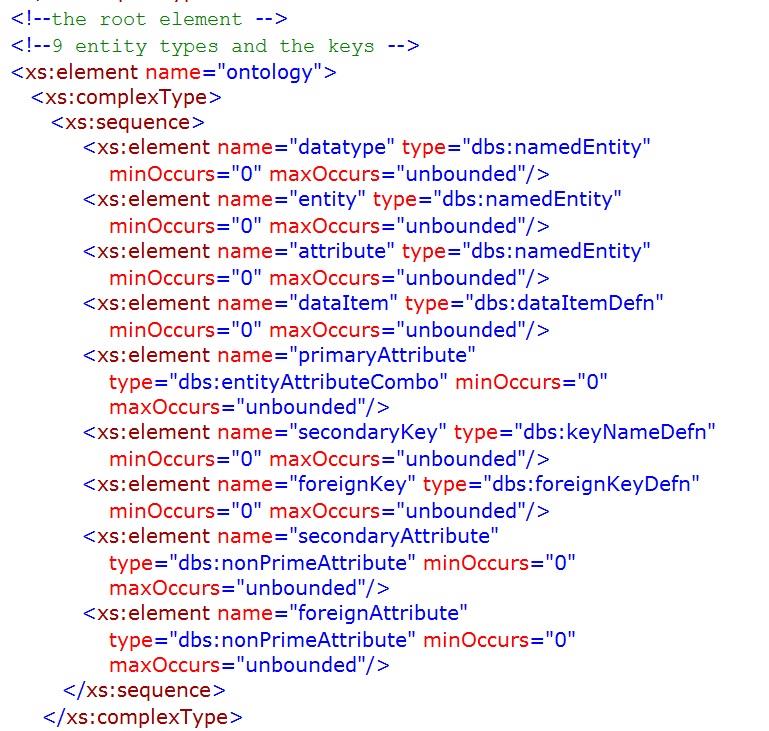

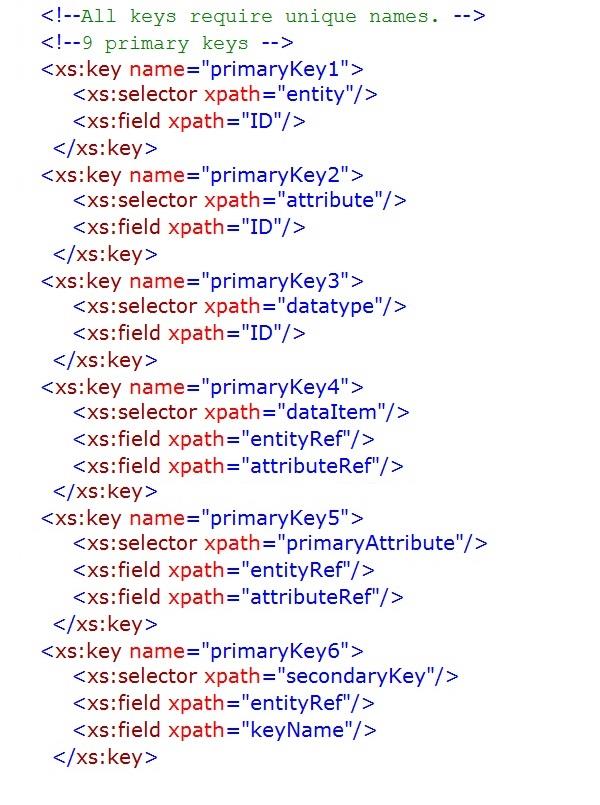

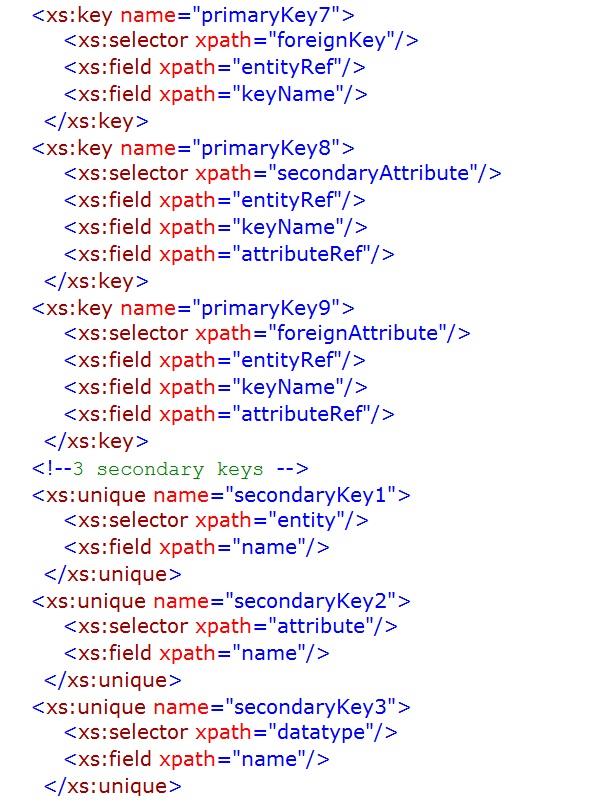

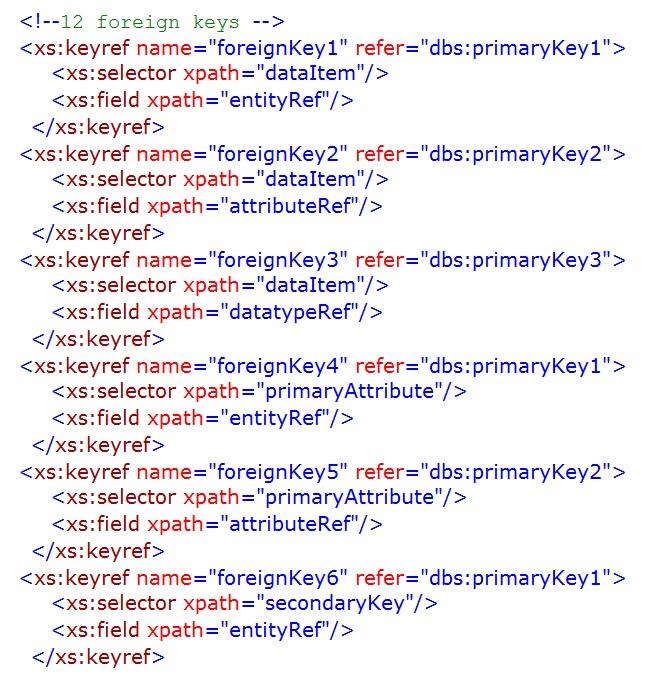

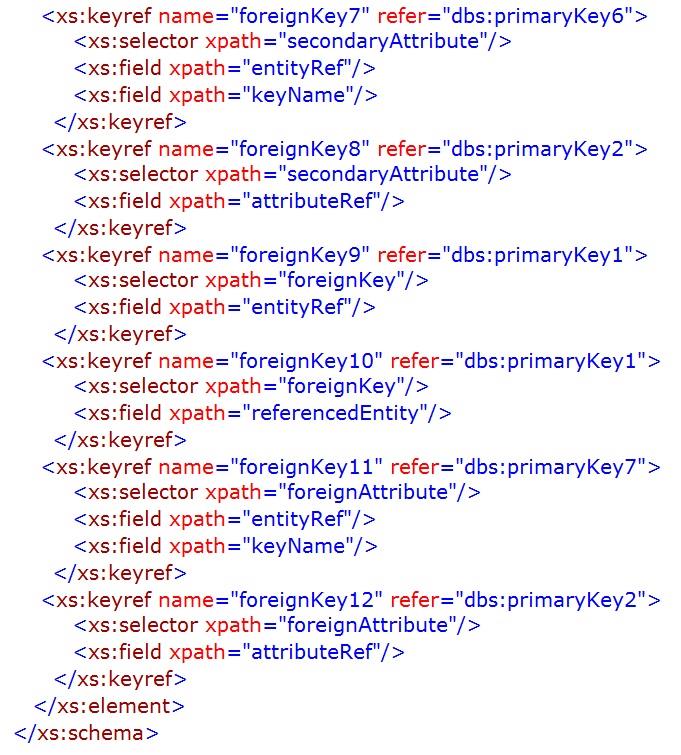

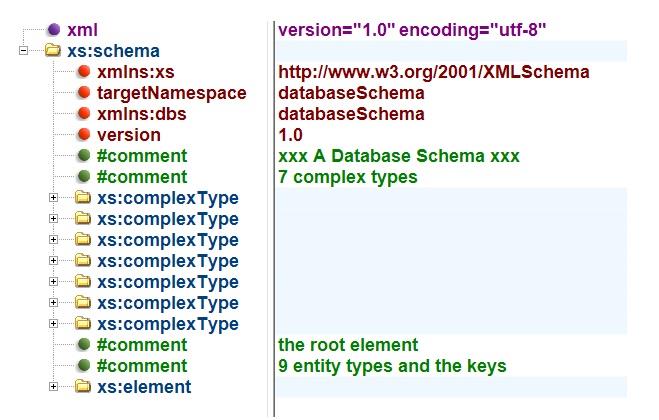

The schema necessary to verify that the instance/XML document above conforms to the database model discussed in the previous chapter is provided below. The outline of the schema is shown prior to the detailed schema being set out.