CHAPTER EIGHT

PUBLIC OR PRIVATE

Treasury’s SOE liabilities headache

Matthew le Cordeur

2016-10-26

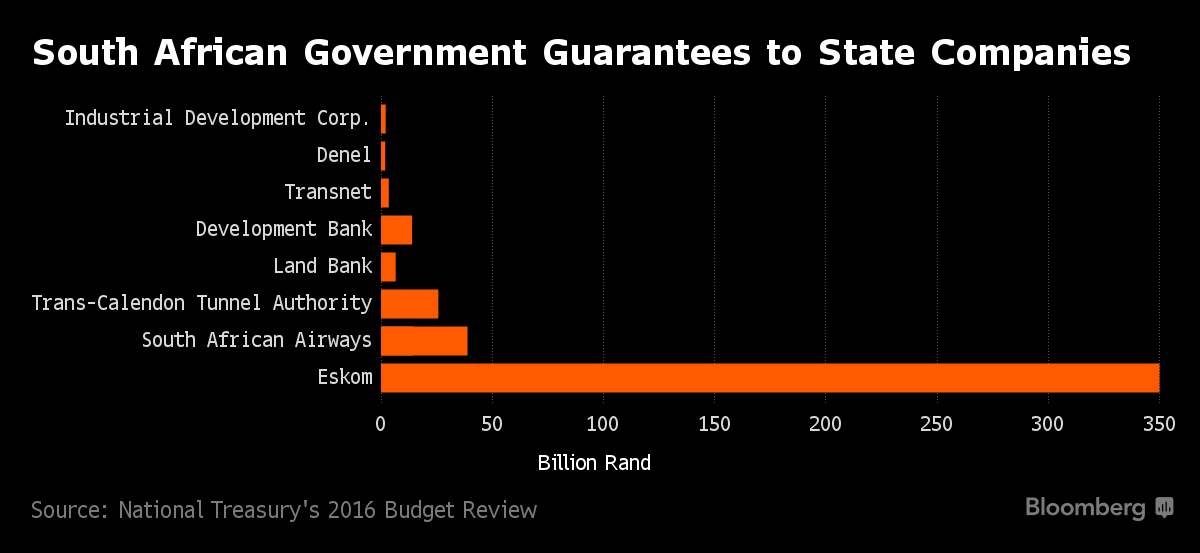

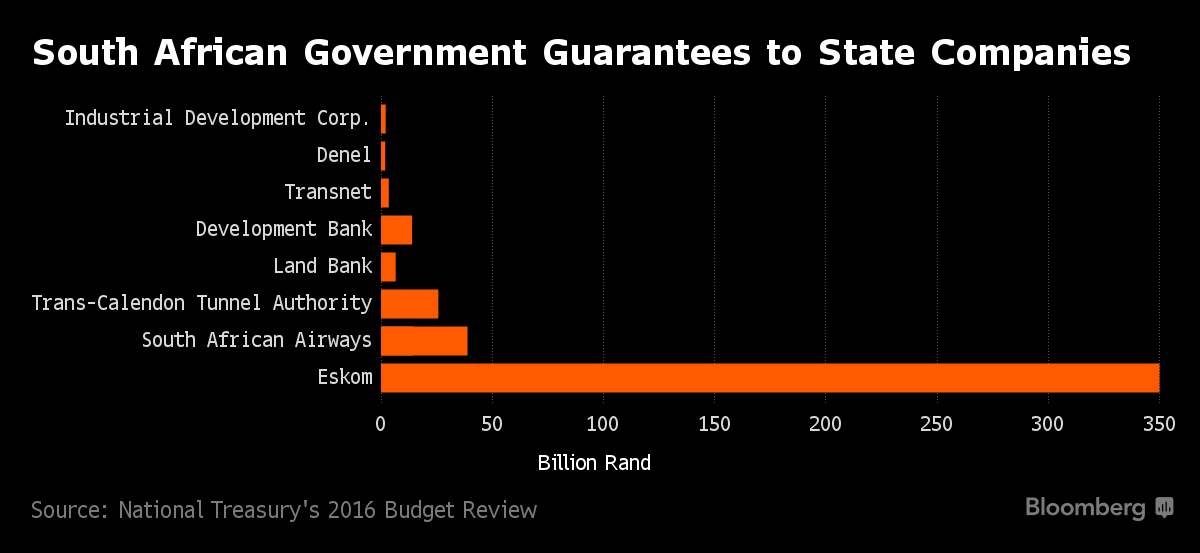

Cape Town – While Eskom took up the biggest chunk of government’s contingent liabilities through its R370bn guarantees, Treasury raised concern over other state-owned enterprises (SOE) in its mini budget.

“Government’s major explicit contingent liabilities are its guarantees, which stood at R469.9bn at the end of 2015/16,” it said in its Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) on Wednesday.

“Total guarantee exposure was R263bn at the end of 2015/16, because several entities had not fully used their available guarantee facilities.

“Government maintains its policy stance that any intervention to support state-owned companies must be deficit neutral,” it said. “Entities receiving support from government will be required to provide sound business plans, improve governance and address operational inefficiencies.”

Apart from Eskom, it listed six SOEs whose contingent liabilities needed monitoring:

1. Prasa: The Fiscus committed R53bn to fund the purchase of new rolling stock and signalling equipment for the Passenger Rail Agency of SA (Prasa). “The auditor general and the Public Protector have found weak expenditure controls and contract management in this programme. This raises concern that Prasa will not be able to complete the programme on time and within budget.”

2. Sanral: Fiscal exposure to roads agency Sanral's debt stood at R35bn as at 31 March 2016. “E-toll collections and auctions are still closely monitored against projected collection levels to ensure recovery,” it said. “If government does not proceed with tolling to fund major freeways, difficult trade-offs will need to be confronted to avoid a deterioration in the national road network.”

3. SAA: Government issued a R19.1bn guarantee to SAA to ensure the company can continue to operate as a going concern. “The carrier continues to post losses,” said Treasury. “There is currently a R14.3bn exposure against the facility. Without the guarantees, SAA is technically insolvent.”

4. SA Post Office: Government has a R4.4bn guarantee exposure to the SA Post Office. “A new board and CEO were appointed, and the company has been able to raise funding to repay creditors, implement a turnaround plan and reach a settlement with labour to mitigate the possibility of strike action,” it said.

5. Land Bank: It got a R6.6bn guarantee in 2014/15, of which R5.3bn was drawn down as at 31 March 2016. The guarantee has helped the bank expand its lending by 10% in 2015/16. “Lenders have highlighted the bank’s strong governance and relationship with the shareholder as reasons to continue supporting its funding programme,” said Treasury.

6. Road Accident Fund: RAF liabilities at the end of March 2016 were revised up to R155bn from the R132bn reported in the 2016 Budget. “These liabilities are projected to grow to R345bn in 2019/20,” said Treasury. “The RAF has been insolvent for over 30 years, despite having a dedicated revenue stream in place to settle claims. Government has not yet tabled legislation to create a new equitable and affordable benefit arrangement to replace the fund.”

Will the ANC turn South Africa into a developmental welfare state?

Mark Ellyne

14 Sep 2016

Mark Ellyne is the Adjunct Professor at University of Cape Town.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

South Africa is grappling with the possibility of a sovereign downgrade by global credit rating agencies. This will bring unnecessary economic costs if it happens.

The health of the country’s state-owned enterprises is a key factor in determining credit ratings, because how they are managed has an impact on the Fiscus. It makes the prevailing political noise around the country’s state-owned enterprises all the more pertinent.

ADVERTISING

Throughout modern history and around the world, state-owned enterprises have played a critical role in shaping successful paths for developing economies.

The good and the bad

When private companies make big mistakes the public doesn’t fret because the private shareholders pay the price. But when state-owned enterprises make losses taxpayers have to pay for their mistakes.

First, let’s be clear that state-owned enterprises are not inherently bad and can be very good. They offer value especially when they supply public goods or fill a natural monopoly. No-one complains that the government spends taxpayer money on public education, national defence or the roads system.

But there is a case for answering the question: why does the government need to own transport companies, military equipment manufacturers, airlines, mining companies or other “commercially oriented enterprises”?

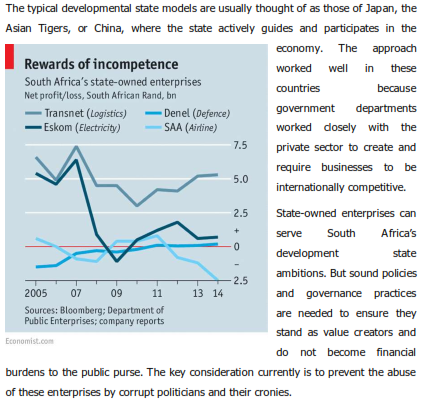

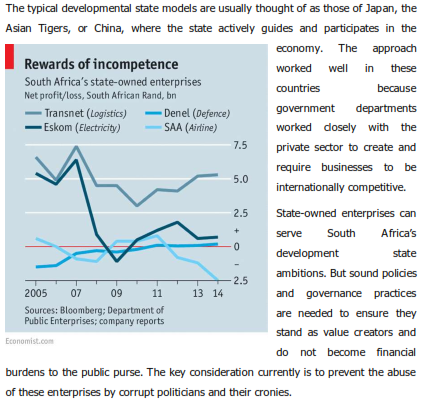

If commercially oriented state-owned enterprises were managed on a commercial basis they would present less of a financial threat to the government and there would be a level playing field in the commercial sector. But the governing African National Congress maintains that state-owned enterprises are not about making a profit.

That may be roughly true about non-commercial state-owned enterprises that produce a net social welfare benefit, but it is no excuse for inefficiency, over-staffing, and high salaries.

When evaluating the use of subsidies to government owned enterprises (that is, they would make a loss otherwise), we need to assess the overall social welfare benefit against the social and economic costs.

The public may be tolerant of giving subsidies to the post office, which delivers benefits to a broad cross-section of the population. But should taxpayers be tolerant of subsidizing an inefficient airline that services the affluent?

Flashing red lights

There have been danger signals from the state-owned enterprises space for some time. A Presidential Review Committee in 2010 concluded that: “The need for another round of large-scale restructuring of public enterprises is definitely eminent in South Africa.”

But little has happened in the way of restructuring proposals.

Instead, the space is dominated by news and allegations of state capture. These include reports that the former finance minister Nhlanhla Nene was fired after refusing to finance new airplanes for South African Airways through a questionable third-party agent.

There are also reports that the current finance minister, Pravin Gordhan, is under pressure for similar reasons.

In light of this, President Jacob Zuma’s move to take control of the special committee that oversees state-owned enterprises has raised eyebrows.

Zuma has justified the move on the grounds that it will ensure that state-owned enterprises are properly governed. But how will he achieve this when his policies and relationships with certain individuals are being called into question?

The private sector is beginning to show concern. This is reflected in a decision by Futuregrowth Asset Managers to suspend funding to state-owned enterprises. Other banks and lenders may follow suit.

This doesn’t mean the state-owned enterprises are in imminent danger. But it does appear that their future financial viability is in question. This is because of government interference in their management in form of cronyism is weakening them.

The developmental state

The majority of the South African economy looks similar to other market economies where a majority of the ownership of the means of production is in private hands.

In a typical market economy, the role of the government is to be the regulator, to guarantee fair play, and to provide a social safety net for those unintended casualties of market dynamics.

South Africa is not far from this model – except that the government has higher than average public ownership of the means of production and worse than average public sector governance. An OECD study of 53 countries placed South Africa as having the 11th largest public sector, and rated it the 15th lowest on quality of governance of state-owned enterprises.

The ANC’s 2007 conference declared its intent to pursue policies that would make South Africa into a developmental state. Its means of achieving this would be through the use the state-owned enterprises to lead and drive economic development.

The Asian model of a developmental state tended to follow a high investment, export-led growth strategy, initially based on low-wage competitiveness. The governments of these countries gave subsidies and protection to big businesses (not labour) in return for their investment to become a global competitor.

Many also consider the Scandinavian economies as developmental states, although they follow a welfare state model of high wages, high productivity and high state social transfers. The Scandinavian economies are already wealthy and tend to be more capital-intensive, whereas the Asian economies are labor-intensive.

The South African government appears to want the impossible solution of living like a Scandinavian welfare state and growing like an Asian developmental state.

This is the unique ANC Developmental Welfare State – but it can’t work now. We want to keep the social welfare net, but the government has to grow the economy, create jobs, and create more wealth. This requires more encouragement and flexibility for the private sector. Why not partially privatize the commercially oriented state-owned enterprises and make them more efficient and competitive?