CHAPTER ELEVEN

BREAKING THE CYCLE OF POVERTY

Education

‘Our issues are unemployment and a terrible education system. It is a disaster. Unless we fix that, we have no hope’.

These are the words of top Private Sector Executive Johann Rupert. He is a man with years of experience in leading people, creating employment, making profits, paying tax and repatriating the proceeds of exports to South Africa. He has immeasurably contributed to the establishment and evolvement of the Small Business Sector in the South African economy. Since introduction this Sector has created more than seven hundred thousand jobs.

If he identifies the resolution of the above two issues as being critical to South Africa’s economic survival, the rest of us had better sit up and take notice.

Clearly education is the key to a livelihood which leads to inclusion in the economy, personal growth and accomplishment of middle class values. As Rupert says ‘Resolution of the education debacle is our nation’s highest imperative. ‘Our issues are unemployment and a terrible education system. It is a disaster. Unless we fix that, we have no hope’.

.

.

However, resolution is proving to be a multi-faceted and complex undertaking.

Perhaps such resolution is being hampered by the cultural divide between the ‘Clever Urban Blacks’ and the ’African Way Rural Blacks’? Or possibly it is being hampered by the greed of the tenderpreneurs who see the education sector as being rich pickings given the size and importance of this sector’s budget allocation? Or perhaps education is seen as a threat by the uneducated members of the Black Elite to their privileged lifestyle? Or perhaps Kleptocrats require uneducated strata of voters on which to prey?

Because of the complexity of the issues involved I have included a broad section of written opinion by knowledgeable writers, authors and journalists. My gratitude for their erudite opinions reproduced here. These help in trying to guage the magnitude of the problem.

South African education system one of the worst in the world

News 24 Correspondent

December 1, 2017

Johannesburg - In the week that South Africa’s matric results were released, international news publication, The Economist, has declared the country’s schools as among the most inept in the world.

"South Africa has one of the world’s worst education systems," the London-based publication reported on its online platform on Friday.

The publication reported that South Africa ranked 75th out of 76, in a ranking table of education systems drawn up by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2015.

Furthermore, reported the publication, in November, a study into trends in international mathematics and science placed South Africa at or near the bottom of a variety of categories - even though its scoring was an improvement from 2011.

The test is written by 580 000 students in 57 countries to determine these results.

South Africa's school results were worse than even poorer countries in other parts of Africa.

"A shocking 27% of pupils who have attended school for six years cannot read, compared with 4% in Tanzania and 19% in Zimbabwe," cited The Economist.

Some of these problems could be attributed to the inequality of resources during apartheid-era Bantu Education, as well as a lack of sufficient teacher training in certain subjects, suggested the publication.

It also laid the blame on the SA Democratic Teachers Union, saying that the report published by academic John Volmink in May 2016, indicated that "widespread" corruption and abuse was occurring.

Furthermore, the lack of government response could be attributed to the fact that "all six of the senior civil servants running education are Sadtu members", claimed the international news source.

And yet money is not the reason for the malaise. Few countries spend as much to so little effect. In South Africa public spending on education is 6.4% of GDP; the average share in EU countries is 4.8%. More important than money are a lack of accountability and the abysmal quality of most teachers. Central to both failures is the South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU), which is allied to the ruling African National Congress (ANC).

The role of SADTU was laid bare in a report published in May 2016 by a team led by John Volmink, an academic. It found “widespread” corruption and abuse. This included teachers paying union officials for plum jobs, and female teachers being told they would be given jobs only in exchange for sex. The government has done little in response. Perhaps this is unsurprising; all six of the senior civil servants running education are SADTU members.

The union’s influence within government belies its claim that officials are to blame for woeful schools. Last year it successfully lobbied for the cancellation of standardized tests. It has ensured that inspectors must give schools a year’s notice before showing up (less than 24 hours is the norm in England). And although parent-led school governing bodies are meant to hold teachers to account, they are more often controlled by the union or in some cases by gangs.

But even if there were better oversight most teachers would struggle to shape up. In one study in 2007 mathematics teachers of 11- and 12-year-olds sat tests similar to those taken by their class; questions included simple calculations of fractions and ratios. A scandalous 79% of teachers scored below the level expected of the pupils. The average 14-year-old in Singapore and South Korea performs much better. Widespread improvement will require loosening the grip of SADTU. In local polls in August the ruling party saw its worst results since the end of apartheid. This may force it to review vested interests. More likely it will continue to fail children. “The desire to learn has been eroded,” says Angus Duffett, the head of Silikamva High, a collaboration school. “That is the deeper sickness.”

On Wednesday, South Africa’s basic education department reported a matriculation pass rate - including progressed students - of 72.5%

Extract from ‘Stepping Stones’

by Bryan Britton 2010

‘In the introduction to this book we quoted John Ruskin, British social commentator (1819-1900) as saying: “Let us reform our schools and we shall find little reform necessary in our prisons”. Unless you have been on an extended visit to Mars you will know that both of these institutions are under severe pressure in the not-so-new South Africa.

The prisons are overflowing. The justice system cannot cope. Offenders enjoy benign bail conditions because there is no room at the inn. This allows them to become repeat offenders without even being incarcerated. Our South African lives, Black, White, Coloured and Asian are worth less than a cell phone. Is this the life God planned for us? Do we ordinary South African citizens, Black, White, Coloured and Asian, deserve this?

I think not.

In a report on education, Jonathan Jansen recently said in a national newspaper: “A five-minute walk through the school and all South Africa’s education problems are on display. The roof is rusted throughout; the toilets stink; litter is everywhere; one teacher is dozing inside a noisy class; and a number of children can be found drifting on a playground.

On to the next school and things get worse. Children are outside washing the cars of their teachers, and a number of adults occupy the school grounds, selling their wares. The school is literally falling apart, with huge holes in the ceiling of the room in which I am to speak. By the time we get to the final school the pattern is familiar; filthy grounds, lacklustre teachers, crumbling infrastructure and poor results”. As ordinary South African citizens, Black, White, Coloured and Asian, should we accept this appalling excuse for the education of our precious youth?

I think not.

A 15-month study of township youths’ morality has concluded that most of them are good kids, but many are neglected. Adult guidance is what is missing from their part-schooled, part-parented lives. Sharlene Swartz, a fellow at the Human Sciences Research Council conducted the research at a school in Cape Town amongst pupils aged between 15 and 19 years. Swartz believes the moral makeup of township youth needs to be the focus of educational attention, and has called for innovative interventions by policy makers and educators.

Skollie Vuma, when interviewed in the study on his take on corruption, said: “If apartheid didn’t affect my parents, then maybe we wouldn’t be staying in that shack house… maybe if my parents were staying in the suburbs, I wouldn’t know about those things (drinking, drugs and criminal behaviour) and I wouldn’t see so many people smoking dagga” Can you argue with that lost young South African’s view?

Young Vuma’s plight is borne out by a recent survey, says Servaas van der Berg of the Department of Economics at Stellenbosch University. An analysis of the earnings of employed matriculants aged 20 to 24 showed that those from households headed by a parent without matric earned on average R2,262 per month, while households with a matriculated head earned on average R4,512 per month. The correlation between education and relative poverty is plainly evident in this small sample.

Unisa’s Bureau of Market Research in their report on personal income patterns and profiles says that there is a strong correlation between education and income levels. Adults with no schooling earn R50,000 per year or less, while incomes between R300,000 and R500,000 per annum were earned by people with a secondary or tertiary qualification.

The survey further notes that South Africa ranked last among 45 countries in 2006 in terms of literacy and mathematics. Further, one white child in 10 and one black child in 1,000 achieves an A aggregate matriculation.

How, in good conscience, are we as a country able to dream of an African Renaissance and spend billions of taxpayers’ funds pursuing this frivolous ideal, when we are last in the class?

The Cape-based Centre for Higher Education and Transformation, together with the University of the Western Cape’s Further Education and Training Institute, in their Ford Foundation funded research, found recently that nearly three million of South Africa’s 6,7 million youngsters between ages 18 to 24 were, in 2007, neither employed nor receiving any form of post-matric training or higher education. Of this idle population 41 percent are Coloured and 44 percent are African.

How can we, as a nation, possibly tolerate a drop-out rate of 64 percent? This is far worse than the 39 percent fail rate for those who actually wrote the matric exam in 2009.

Education expert, Graeme Bloch, says: “It’s a ticking time bomb. An enormous number of children will not be doing very much with their lives and will probably not get a second chance at basic education”.

How the poor South African economy has continually absorbed these horrific numbers of lost children each year, over the last 15 years, is indeed a miracle. Certainly, this aggregate of lost children is growing to become a very significant portion of the Rainbow Nation.

Graeme Bloch continues: “It will take about 30 years to fix this problem. By then the dropouts from the 1998 generation will have been unemployed for most of their adult lives”.

Veteran journalist, Allister Sparks, further highlights this debacle: “We have betrayed a whole generation of young people and left more than a million of them with no prospects for the future. That is failing in a sacred responsibility that the ANC had to the youth of this country. For it was the youth, more than anyone else, who fought the real war of liberation in this country.

They represent the future, and to fail them is to ensure the failure of the future of South Africa.

A subject so grave it must surely top the ‘to do list’ of the President. Alas no. He gives credence instead to the notoriously retrogressive SA Democratic Teachers’ Union (SADTU) backed by that ever grasping dalliance partner, Cosatu. Over the past five years SADTU has the dubious distinction of topping the list of days lost through strike action. Of all working days lost in this period, 42 percent were incurred by our infamous teachers’ union. Our issues are unemployment and a terrible education system. It is a disaster. Unless we fix that, we have no hope.

Andrew Levy, veteran labour specialist, says: “We hope one day teachers will realise their moral obligation and use strikes responsibly”. Servaas van den Berg, Professor of Economics at Stellenbosch University, adds: “Strike action puts at risk the chances of children getting a good education”. And economist Mike Schussler goes as far as saying: “SADTU is keeping apartheid alive”.

So, let me try to understand. The future of South Africa lies in the hands of the youth of the nation. The key to that event lies in the education of that youth. The success of that endeavour depends on teachers being at school to teach and having the moral obligation and incentive to teach. And finally, the government having the will to ensure that education is prioritized above all else.

That scenario seems too simple.

Perhaps those entrusted to execute these plans have a greedier and more devilish agenda’.

South Africa’s education crisis

Felicity Duncan

17 January 2012

The ANC itself has admitted that education is in a crisis. In a recent statement, the party wrote, “We have made progress in building a single, non-racial, non-sexist and

national public education system, and have reached near universal enrolment in primary and increasingly in secondary education. However, major challenges remain – in particular the huge challenge of the quality of education and throughput rates at all levels of the our education and training system. This constitutes a crisis, with South Africa performing poorly in comparison with other peer countries on nearly every single education indicator.”

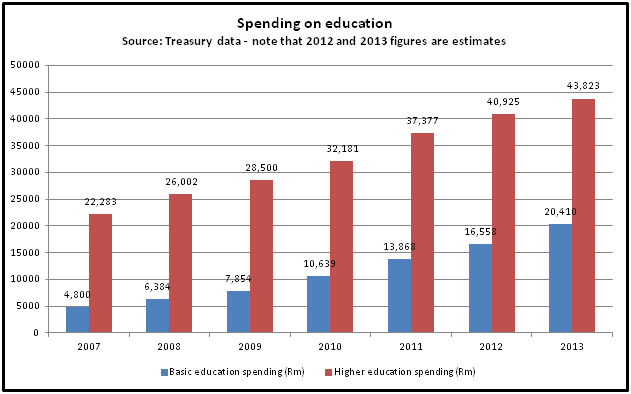

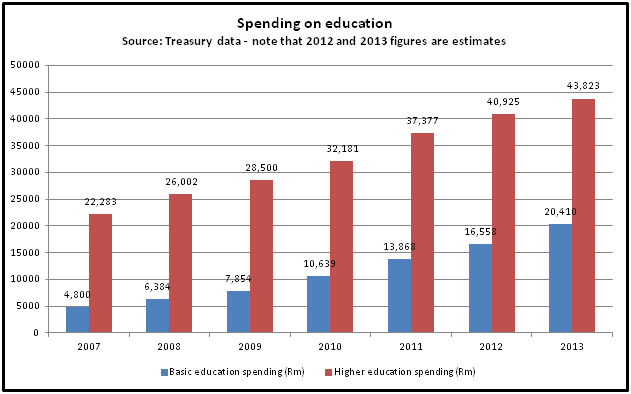

The crisis is real, but what is the underlying issue? It’s not money. As the chart below shows, South Africa spends plenty on education, and that amount has been growing every year. Overall, South Africa spends over 5% of its GDP on education, putting it broadly in line with countries like the USA, the UK, Holland and Austria.

But if the problem isn’t money, then what is it? Unfortunately, while the ANC’s document recognises the crisis and calls for “urgent and practical action” to fix it, there isn’t much in the way of ideas. This isn’t unusual. Education is in crisis everywhere, and no one is quite sure how to fix it so that it works in the modern world. There are, however, a few recommendations that seem to apply globally.

1. Recruit and reward excellent teachers, and fire bad ones. A good teacher can make a world of difference to learners’ achievements, and a system for assessing performance and for rewarding and punishing teachers according to performance is vital.

2. Use technology. Technology is a good way to engage students, and to ensure that the same quality materials are being used across the board.

3. Get parents involved. Having parents who help with homework, books in your house, and a family that values education is absolutely vital to the success of any learner. The ANC must include a broader family-focused effort in its attempts to save South Africa from its educational crisis.

4. Design a syllabus for the world and the country as it is. There is a tendency in the ANC to attempt to create an ideal world, rather than deal with South Africa as it is in reality. The SA curriculum must be designed with a realistic idea of the country’s resources and the kinds of jobs learners will be able to find. Sensible curriculum design should be a major goal.

Economies grow when early childhood development is a priority

Linda M. Richter

December 6, 2016

The first 1000 days of life – the period from conception to the age of two – are pivotal for any human being’s development. This has been shown repeatedly by every science that studies early childhood development: anatomy, epidemiology, genetics, immunology, physiology, psychology and public health.

And it is confirmed in several papers and commentaries in a Lancet series I led in my capacity as a distinguished professor at the University of the Witwatersrand and Director of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development. Our newest work powerfully demonstrates that low-cost interventions which facilitate and support nurturing care for infants in their first years of life contribute to lifelong health, wellbeing and productivity. The economic benefits of these interventions far outweigh the investment costs.

Simply put, we need to intervene earlier than we currently do. In South Africa for instance, a great deal of emphasis in early childhood development (ECD) is placed on subsidizing three and four-year-olds to attend crèches and play centres. Early learning in preschool is important. But it is less effective than it could be because children’s foundational skills and capacities are laid down at a younger age – in the first 1000 days.

A cycle of poverty

Poor childhood conditions, such as exposure to poverty and stunting, are associated with long-term disadvantages to health, education, social adjustment and earnings.

In South Africa, 63% of children younger than 18 live in poverty: that is, on less than R923 a month or R31 a day. And 27% of 0-3 year olds are stunted, a condition which results from long-term undernutrition, mainly of essential vitamins and minerals. This hampers the development of lean mass – skeleton, brain, internal organ size and function.

Children living in poverty and who are stunted tend to go to school later. They also tend to learn less, pass fewer grades, leave school earlier and earn less as adults. In turn, their children are more likely to grow up in poverty, lacking essential nutrients and learning experiences, trapping families and children in poverty for generations.

It is this negative cycle that most concerns politicians and economists. Countries can’t grow at the pace of their most able people because too many children and adults are left behind. The Lancet series estimates, globally, that individuals who experienced poor early development suffer a loss of about a quarter of adult average income a year. This makes their families poor too.

Importantly, these negative individual effects add up. Studies in several African countries estimate that the cost of hunger – the knock on effects of stunting on learning and earning – is 10.3% of GDP in Malawi, 11.5% in Rwanda and 16.5% in Ethiopia. In South Africa we estimate that stunting results in a loss of future earnings of 1.3% of GDP, or R62 billion per year.

The series also estimates what poor early development costs countries, by comparing the future costs to current expenditure on health and education.

For example, Pakistan is estimated to lose 8.2% of future GDP to poor child growth. This is three times what it currently spends on health as a percentage of GDP (2.8%).

Countries that do not improve early childhood development are fighting a losing battle.

Nurturing care

Babies need love, care, protection and stimulation by stable parents and caregivers. In The Lancet series, this is referred to as “nurturing care”. Breastfeeding is a good example of nurturing care. Nurturing care can break down under conditions of severe stress and struggle.

Extremely poor families find it hard to provide nurturing care for young children. They sometimes don’t have the means for health care or nutritious food. They may be so emotionally drained by daily struggles that they feel unable to show interest in or encourage a young child. There are several ways in which governments and social services could support such families.

For instance, national policies can support families financially, give them time to spend with their young children and improve access to health and other services. Minimum wages and social grants protect families against the worst effects of poverty. Maternity leave, breastfeeding breaks at work and time for working mothers to take their children to clinics and doctors are also crucial.

Other meaningful interventions include free or subsidized health care, quality and affordable child care and preschool education.

Many politicians and policymakers may fear that dedicated early child development is beyond their budgets. As I’ve already pointed out, the return on investment of such programs is substantially more than the cost of implementing them. But The Lancet series went further: we modelled the cost of adding two early child development programs to existing packages of maternal and child health services.

A worthwhile investment

The first programme is community-based group treatment for maternal depression. Addressing maternal depression is important because it adversely affects a mother’s ability to provide nurturing care. The second programme is a child development stimulation programme, Care for Child Development, which can be implemented in health care facilities or in community programs.

Our research modelled the cost of expanding these programs to universal levels in 73 countries that experience a high burden of child mortality, growth and development. The cost of bringing both programs to 98% coverage over the next 15 years is US$34 billion.

The additional cost for the supply-side of the programs in the year 2030 is on average, 50 US cents per capita. This varies from 20c in low income countries where costs are lower, to 70c per capital in middle income countries.

The evidence consolidated in this series points to effective interventions and delivery approaches at a scale that was not envisaged before. During the next 15 years, world leaders have a unique opportunity to invest in the early years for long-term individual and societal gains and for the achievement of the sustainable development goals.

Is South Africa's education system really in crisis?

By Milton Nkosi BBC News, Johannesburg

29 January 2016

South Africa's minister of education openly admits that the country's schools are in a state of crisis. How did we get here and what needs to be done?

Angie Motshekga did not mince her words when she addressed her colleagues at a recent African National Congress (ANC) gathering.

"If 25% of students fail, we must have sleepless nights," she is quoted in local media as saying.

"This is akin to a national crisis."

Not about the money

The shocking statistic is that some 213,000 children failed their end of school examination for the academic year ending last month, out of a total of nearly 800,000.

But that is just half the story, as there is also a massive drop-out rate.

According to Stellenbosch University's Professor Servaas van der Berg, out of the 1.2 million seven-year-olds who enrolled in Grade 1 in 2002, slightly less than half went on to pass their school-leaving exam, the matric, 11 years later.

This is not about a lack of funding. In fact, South Africa spends more on education, some 6% of GDP, than any other African country.

But quality education for everyone is not there, as in many global studies South Africa often comes near the bottom in mathematics and science tests.

The cancer lies deep in the education system and the continuing legacy of apartheid, and parents know this.

'Packed like sardines'

One of the most depressing sights in post-apartheid South Africa is the bussing of black children out of townships like Johannesburg's Soweto.

Children are packed like sardines into mini-buses and driven long distances, some over 30km away, to the schools in the former whites-only suburbs.

Some will be travelling to private schools, but the majority goes to the state-funded schools which are better resourced and have better teachers than their equivalents in the townships, mirroring the situation during apartheid.

At that time, the white minority government spent four times more on a white child's education than it did on a black child. This disparity is no longer the case, but the legacy is still there.

Leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance Mmusi Maimane explained the legacy of that system recently when he spoke about the scourge of racism.

"We are entitled to ask why a black child is 100 times more likely than a white child to grow up in poverty," he said.

"We are entitled to ask why a white learner is six times more likely to get into university than a black learner."

Rather than disagree, the education minister chimes in.

"Twenty years down the line we still have the legacy of apartheid," Ms Motshekga told the BBC, "we still have teachers who were not trained for the future".

Poor teaching

There are many schools in the townships and the government has built more schools in these areas since the advent of democracy, but quality teaching and a proper structured learning process is lacking.

The most tragic anecdote of how serious the problem is comes from a World Bank study conducted in rural Limpopo province back in 2010.

The study asked 400 12-year-old students to work out the answer for 7 x 17.

To work it out, the pupils first drew 17 sticks and counted them seven times. Some 130 of the 400 got the right answer.

But when the same question was presented in word form in English, things spiraled downwards.

Researchers asked the students: "If there are seven rows of 17 chairs how many chairs are there?" None of the children answered correctly.

So language and the quality of teachers are huge areas of concern.

There are 11 official languages in South Africa but most teaching is in English, especially for subjects such as mathematics and science.

Professor John Volmink, chairman of the education quality assurance body Umalusi, has studied the relationship between the language of instruction and how students perform.

"It remains true that candidates writing the examination in a language other than their home language continue to experience great difficulty in interpreting questions and phrasing their responses," he is quoted in the City Press newspaper as saying.

"Teachers' knowledge of English has to be upgraded. Unless we support them, results will continue to drop."

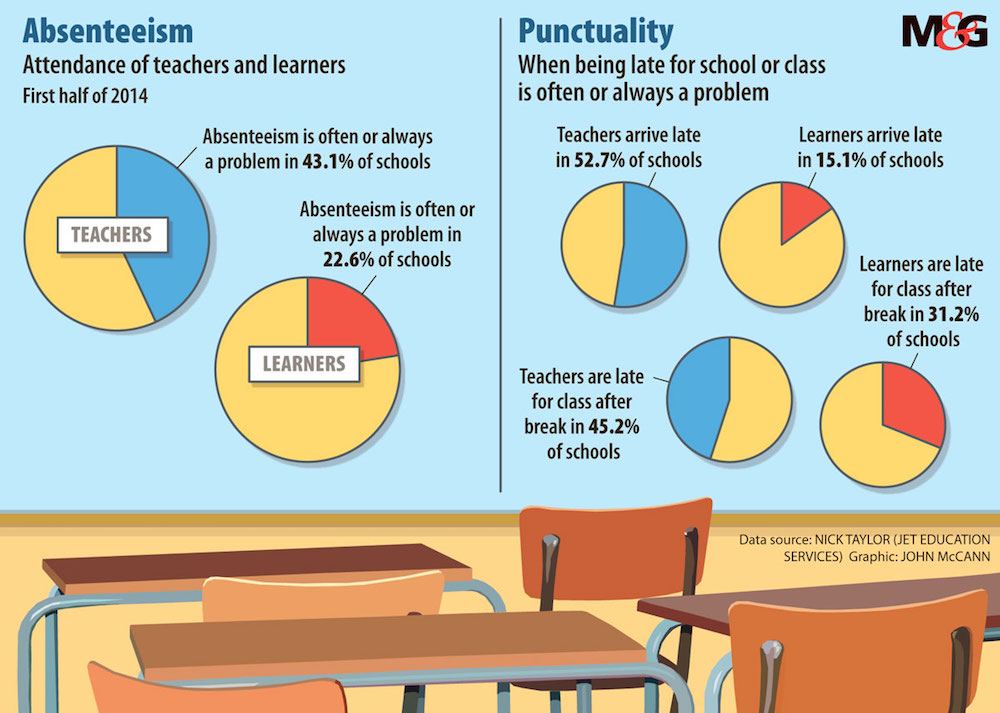

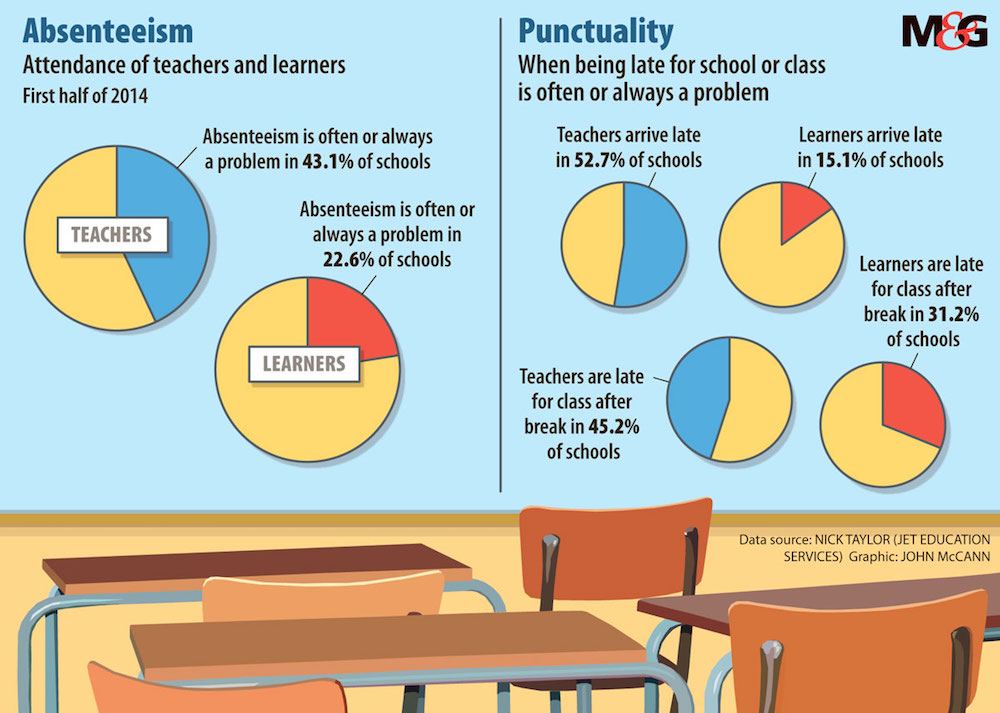

All of that aside, the education minister is also taking on the unions, who are seen to be part of the problem by appearing unwilling to tackle absenteeism.

Some teachers are not turning up to work for parts of the week, which means that students over time can lose out on months, if not years, of learning.

But Ms Motshekga told the BBC that she wants to take the politics out of education.

"I fight a lot with unions behind closed doors, I don't call the media to make a show of it," she said.

"I do it responsibly in a manner that corrects the wrong but keeps the system together."

'There is hope'

But with all of the above, it is not all doom and gloom.

There are schools which continue to produce go

.

.