CHAPTER TWELVE

WOMB TO TOMB WELFARE

‘So Pierre I need to know what made you a racist.

‘I am no racist. I simply dislike Blacks’.

‘That is a little extreme old chap. I know many people of color and they are mostly polite, humble, helpful and extremely loyal’ said I. ‘Yes, but they are all lazy and they are uneducated’ fired Pierre back.

‘Again Pierre, I must disagree. You are making a terrible generalization. Besides, do you not think that fifty years of Apartheid Rule had something to do with the educational disparities inherent in our society?’

‘Ja, but they do not like to work’.

‘I will remind you that the first world environment in South Africa was created on the back of black labor. And may I add that labor was obtained at starvation wage rates’. ‘Well, whatever, they had just better stay out of my way’.

‘Pierre, I must take the strongest exception to your attitude. We cannot hope to correct the income disparity divide nor the education backlog with citizens with an attitude like yours. South Africa deserves an all-inclusive citizenry where political rights and economic rights are enjoyed by all. To heal our nation we need a far more forgiving attitude and that starts with the haves, which happens to be us’.

‘Do want some more Unbelievable?’ proposed Pierre

‘Do not try and change the subject and yes, thanks’

‘Look Bryan, I respect your views but these guys now have the steering wheel and where have they driven the South African car? Over the cliff that is where. A small cabal of them have robbed the coffers and made South Africa, both black and white, the basket-case of Africa and the World.

‘So what are you going to do about it’ said I forlornly

‘Move to Turkey’ countered he.

Races apart – can we still be friends? – Pondering the barriers

By Sisonke Msimang

Sisonke Msimang is a Ruth First Fellow, Journalism at the University of the Witwatersrand. This was originally published as the Ruth First Memorial Lecture in 2015 and is an edited extract from “Ties that Bind: Race and the Politics of Friendship in South Africa” (Wits University Press), edited by Shannon Walsh & Jon Soske.

whatsapp

In courageously broaching the question of whether South Africans can be friends across ‘racial’ boundaries, Sisonke Msimang, goes to the heart of the historical inequalities that the architects of apartheid so successfully left us with. If the personal is the political then here’s a quick tale. I grew up at a trading store in the remote KwaZulu Natal thornveld, 30 km from the nearest village (ironically enough, the then unknown and very colonial Nkandla, home to President Zuma). I spoke fluent Zulu before learning English at a Catholic Missionary boarding school in Eshowe. My best childhood friend was Nonhlanhla Shezi. We built cardboard box trading stores and sold sweets for pocket money, fished for scaly in the rivers and streams, walked cross-country to Nkandla once, stopping off for refreshingly sweet Mahewu drinks at kraals along the way. Nobody thought twice. ‘Umfana wase-Dlolwana’, our hosts would explain to anyone questioning the presence of this pale child. Almost 20 years later, now living in a leafy family suburb of Pietermaritzburg, I heard our Alsatian barking madly at someone seemingly asking for work at the gate. I’ll never forget when I ‘’kuza’d’’ (restrained) the dog and engaged with the young Zulu man, asking if I could help. His expression was reproachful when he asked if I recognized him. Nonhlanhla. We tried to catch up over coffee in the kitchen where Makhanyile, our house-help and cook, was visibly uncomfortable – as were we. Could we still be friends across racial boundaries? Time and apartheid had inserted an undeniable wedge. Are we still friends? No – I have no idea of what became of him. One of my best friends was a Zulu. Does speaking that truth make me a racist today? I fervently hope not. But it does illustrate the vital complexities that Msimang grapples with below. – Chris Bateman

Now that the season of realpolitik is upon us in South Africa and the rainbow nation myth is receding we must ask ourselves whether we still need a framework of reconciliation that presupposes friendship across the races as an important and useful barometer of the health of the nation.

Some will argue that the question of friendship is frivolous. They will say we must be more concerned with matters of politics and economics than of emotion, and that we don’t need to be friends; we simply need not to interfere with one another’s destinies. Others will insist that we must indeed be friends. They will wring their hands and argue that to abandon the idea of friendship is to abandon an important national ideal and perhaps to abandon a peaceful future.

Perhaps counter-intuitively we must hold on to both instincts. On the one hand, our progress in improving the conditions of black people must be central and must be guided not by a desire for blacks and whites to be friends, but by the need for black people to live dignified and equal lives that are commensurate with those of their white compatriots.

In defence of this, we must be prepared to alienate whites (and for that matter blacks) who do not accept this as a fundamental reality. We must accept that they might leave and seek their fortunes elsewhere and this must not concern us.

On the other hand, we must accept that although the notion of interracial friendship has sometimes threatened to overshadow the importance of black dignity, it is crucial that we keep its possibility alive. This, even as we tend to the more urgent matters of preserving and elevating the meaning of black personhood because this is the basis upon which a genuine and robust culture of respect in contemporary South Africa will be built.

Interracial respect

To even begin to talk about interracial respect in modern South Africa is difficult because so much unintentional damage was done by our country’s first iteration of reconciliation; what I refer to as Reconciliation 1.0. There were many laws in that first version.

Yet in light of palpable anger and discord on race in recent years, we have a new opportunity to develop a more honest code: call it the open source version. Indeed the seeds of this are evident in the activism that swept our country in 2015.

South African students are at the forefront of designing the upgrade, and the next generation will owe them a debt of gratitude.

Ironically, perhaps, in thinking about how we deepen this new code we must stretch our minds back to ancient times, to the Greeks, to Aristotle in particular. For Aristotle, philia was the most perfect form of friendship. The great philosopher suggested that there are three kinds of friendship:

-

friendships of convenience, where the parties interact, for example, in order to do business or Black Economic Empowerment deals;

-

friendships of pleasure, where if the pleasurable thing, say drinking or smoking crack, disappeared, then the friendship would too; and

-

friendships of character, in which “one spends a great deal of time with the other person, participating in joint activities and engaging in mutually beneficial behaviour”.

In this view:

Between friends there is no need for justice, but people who are just still need the quality of friendship; and indeed friendliness is considered to be justice in the fullest sense.

In other words Aristotle argued that between real friends, there is seldom need for the interventions of outsiders; justice is made possible by the nature and depth of the relationship. In short, where there is trust, there is no need for strongly enforced rules. By extension then, those who consider themselves to be good and moral cannot be truly good or moral if they do not have the “friends” to prove it.

Millions of black potential “friends”

For the white South African, who is surrounded by millions of black potential “friends”, the implied question in Aristotle’s framing of the relationship between friendship and justice is, “Are you just?”

Because of our history, this moral and practical question is especially directed at white people. Friendship should and must be of great ethical and philosophical concern for whites. In general, white people in this country should worry and be pained by this matter in ways that black people need not be, for obvious reasons of demography and history.

If we are to replace the distorted and falsely optimistic vision of the rainbow with a more honest but no less aspirational vision of dignity and respect, whites will need to give up their ideological and practical specialness. They will also have to reject the increasingly irrelevant, weepy, and unhelpful mythology of “Rainbowism”.

Those who are truly invested in the future of this country will also have to stop hiding behind their emotions and their tears whenever the subject of race comes up.

One of the tenets of the rainbow era was that those of us who extended our hands across the racial divides were thwarting racism.

If the racist hates it when children play together, then surely those of us who encourage our children to interact are not racist?

Unfortunately it is not so simple. Friendships involving people who are more powerful than us have seldom served black people well. The power imbalances are too great, the possibilities for manipulation and domination even by those with good intentions are simply too high to assume that light friendship is the answer.

Friendship is not free of responsibility

Today, a generation into democracy, young black people raised to believe that friendship across the races is an indicator of progress are questioning this. They are asserting that friendship, if you want it, is not free of responsibility.

Some of them are going further to say that friendship is simply not on the cards for them.

In a South Africa trying desperately to figure out a way forward these assertions are not easy to speak aloud. Yet they represent a recalibration of our aspirations.

Some people are worried by this: They are scared of what they call “separatism”.

I am not, mainly because this sort of robust honesty does not mean that we have abandoned the idea that “race” is an empty construct that should neither bind nor divide anyone. We can both believe in the need for a just world in which race is meaningless, and accept that in this time and place, “race” is a term that is bursting with meaning.

Can we be friends across these “racial” boundaries? Yes, we can. And no, we cannot. It’s that simple and that complex.

It is the struggle for understanding the complexity of this paradox that must enthuse and inspire us.

This is an overview of South Africa’s social grant system

By Gabrielle Kelly and GroundUp Staff

6 July 2016

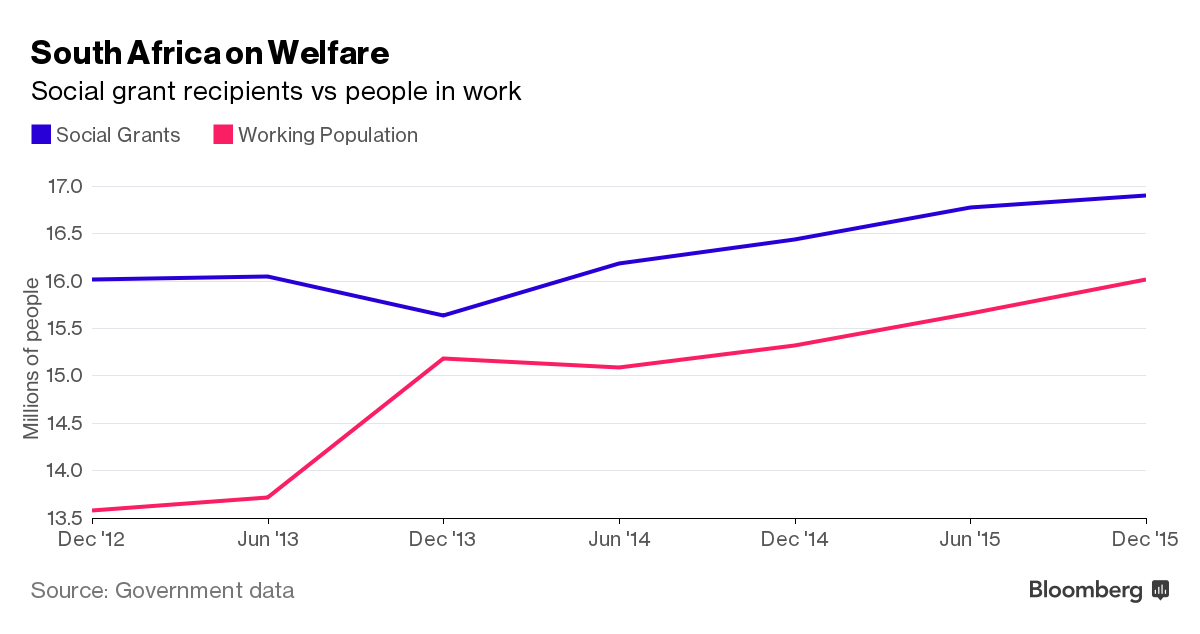

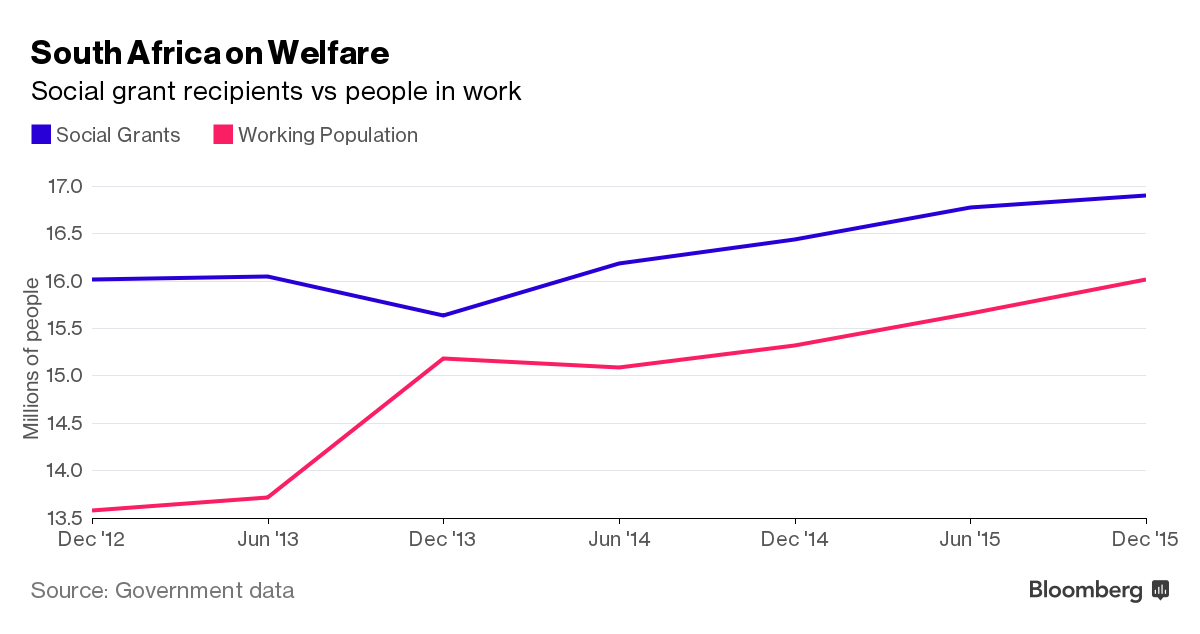

For a developing country, South Africa has a well-established social welfare system and a large proportion of social spending goes towards social grants. Over 16 million South Africans receive social grants.

Social Grants are in place to improve standards of living and redistribute wealth to create a more equitable society. Sections 24 through 29 of the Bill of Rights in the South African Constitution recognised the socio-economic rights of citizens, including the right to social security. The government is obligated to progressively realize these rights, meaning that “the state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realization of the right.”

Social grants are administered by the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA). SASSA is mandated by the South African Social Security Agency Act of 2004 to “ensure the provision of comprehensive social security services against vulnerability and poverty within the constitutional legislative framework”.

The Social Assistance Act of 2004 and regulations to the act provide the legal framework for the administration of seven social grants. Grants are targeted at categories of people who are vulnerable to poverty and in need of state support. These are older people, people with disabilities and children. Also, the Social Relief of Distress award provides immediate temporary assistance to people in dire need of financial support and is given to people in the form of vouchers, food parcels or money for a three month period.

Grants available include:

-

Child Support Grant

-

Older Person’s Grant

-

Disability Grant

-

Grant-in-Aid

-

Care Dependency Grant

-

War Veteran’s Grant

-

Foster Child Grant

Applicants for social grants must be South African citizens, permanent resident or refugees and currently living in South Africa.

The looming pension’s crisis

There’s no evidence Sassa is ready with the complex systems and infrastructure needed to disburse R140bn each month, on time, to the right people

09 December 2016

Just last month, the Department of Social Development tabled its long-awaited and sweeping proposals for comprehensive social security reforms. Whether SA can afford these is far from clear and they need robust debate.

But it seems frighteningly ironic that the department can make such far-reaching policy proposals when it is clear it cannot guarantee 17-million poor South Africans that they will continue to receive their monthly social grants come April 2017. That is when the controversial contract with a private sector provider to pay the monthly grants expires – and when the department’s own in-house agency claims it will take over the task.

There has been no evidence that the South African Social Security Agency (Sassa) is ready with the complex systems and infrastructure needed to ensure that the annual grant money of R140bn is paid out each month, on time, in the right amounts, to the right beneficiaries, even in SA’s remotest rural areas. And the recent highly unsatisfactory parliamentary engagements on the subject by Social Development Minister Bathabile Dlamini and her team have raised deep concerns.

The government’s existing policy of social protection for the most vulnerable citizens — the elderly, children and disabled people — has been far and away its most successful intervention to combat poverty and reduce inequality in the democratic era. The grants are the largest single item of government spending, accounting for 3.2% of SA’s GDP and more than one-eighth of the government’s noninterest expenditure. They have been growing ahead of inflation at about 8% a year, enabling millions of households to buy bread, pay for schooling and transport, and generally stay alive despite high levels of unemployment and working poverty in the country.

SA’s social protection system, which has a far greater re-distributional effect than those of most other emerging markets, should continue to be a source of pride to all of us and equally a source of stability for the country. But that depends on a successful payment system.

The existing contract with service provider Cash Paymaster Services has a long and turgid history going back to the early days of democracy when the government successfully outsourced the task of paying the grants to three service providers in the different provinces.

It then centralized the system in Sassa and went out to tender for new providers, attracting some innovative and impressive bids from a number of consortiums that included most of SA’s big banking groups. That didn’t seem to be good enough for Sassa, which instead ended up awarding the contract to Cash Paymaster Services amid question marks about alleged corruption and impropriety.

After the Constitutional Court threw out that contract and mandated Sassa to go out to tender again, imposing strict conditions, Sassa proved unable to pursue the process with any effectiveness, extending Cash Paymaster Services’ contract and ultimately deciding it would do the job itself.

Just what possessed a government agency with a less than impressive track record to think it could take on so mammoth and complex a task — in which one of SA’s big banks and other private sector players would once have been quite willing to invest — is a mystery. Why Parliament permitted this absurdity is a puzzle too.

At this stage, though, the challenge is to ensure that 17-million people continue to receive their money. A first step is to get honest answers out of Sassa about how far it is with the process and whether it even understands the challenges. Parliament should continue to press hard, but firm intervention is surely also needed from the top of the government itself.