The Historic Background

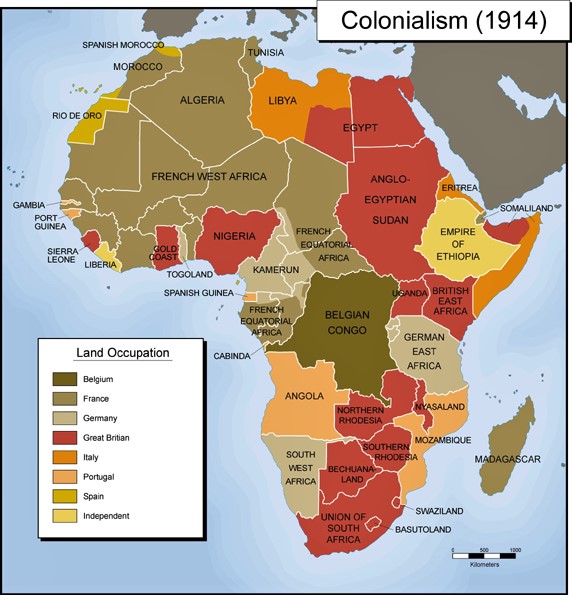

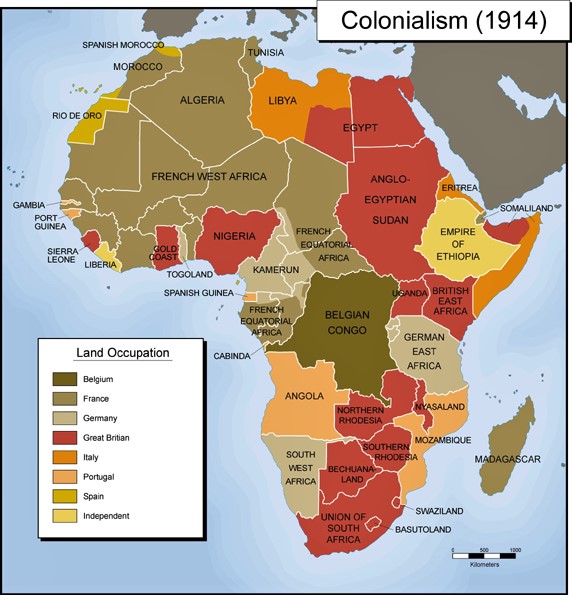

These encouraging South African political events need to be viewed against the broader developments in Africa and the rest of the world at that time.

South Africa was the last to be decolonized on the African continent and until 1994 was governed by a majority of white only voters. On ascension to full one man one vote democracy, the country became the fifty fourth nation on the African continent to throw off the shackles of colonization. The liberation movement, the African National Congress, was voted into power by a considerable margin in the first fully democratic election.

To put the events of 1994 into context, the decolonization movement prior to then needs examining and a succint account of this period is found in extracts from William Woodruff’s ‘A Concise History of the Modern World’ and specifically the chapter ‘The Decolonization of Africa’.

|

|

William Woodruff is Graduate Research Professor (Emeritus) in Economic History at the University of Florida, Gainesville. He holds degrees from the Universities of Oxford, London, Nottingham and Melbourne (honorary).

He says ‘The declaration of principles by Churchill and Roosevelt in the Atlantic Charter in 1941, with its promise of self-determination and self-government for all, heralded the end of European colonization in Africa. As the Second World War progressed, a new generation of black leaders, intent on obtaining self-rule, emerged out of the native resistance movements’.

|

‘By and large, the European nations were as glad to surrender political power as the native leaders were to assume it. When one compares the struggle for independence in Asia, African independence – with the exception of Algeria – was won quietly and with relatively little bloodshed; in some cases, it was thrust upon those who sought it’.

‘When one considers African traditions, and the desperate economic conditions of so many Africans, it was perhaps foolish to have expected Africa to adopt Western ways. With a tradition of hierarchical tribalism, Africa has never been disposed to democratic politics. While the number of democracies in the world is on the rise, Africa was not much closer to democratic rule in 2005 than it was in 1950. What the West understands as freedom of the individual under the law has still to be achieved. Where the rule of law has gained a foothold, it has often been broken by democratic leaders’.

‘In many African countries, free elections and a free press (as the West would define them) are not tolerated; nor is an independent judiciary.

The Western idea of freely held multi-party elections is not widespread. Too many governments do not have a ‘loyal opposition’; they have political enemies. Elections are a means of conserving power, not introducing democracy. In a continent where power is personalized, few presidents have ever accepted defeat in an election. Concentrated rather than shared, power is the ‘African Way’.

‘Having removed the colonial yoke, Africans now bear a yolk of their own making’.

‘Independence from colonial powers has not only brought widespread violence; it has brought a deterioration of Africa’s economic lot. It is the world’s poorest, most indebted continent; the debt repayments of some countries exceed the amount being spent on health and education’.

‘By holding the West responsible for the continent’s extreme poverty, internal wars, tribalism, fatalism and irrationality, autocracy, disregard for the future, stifling of individual initiative, military vandalism, staggering corruption, mismanagement and sheer incompetence, Africans are indulging in an act of self-deception’

‘A similar colonial background has not prevented certain Asian countries from achieving rapid economic development. Africa cannot hope to escape from its present economic and political dilemmas by placing the blame on others’

‘If Africa is to pay a necessary and constructive role in the world community, it must first rediscover itself. Only Africans really know where they have been and where they might hope to go. They do not have to have Western values and Western goals to become economically viable; their cultural values are too deeply planted for that to happen. Western values and goals may be entirely inappropriate for them. Nor does their performance have to be judged by Western standards. Ultimately, African intrinsic values and goals must prevail. African ideas, confidence and resolve, rather than foreign leadership and foreign aid - much though it is needed – will eventually determine Africa’s future. The continent’s human qualities and its rich natural resources offer great hope’.

Before delving into the complex issues of Financial Freedom and the nine priorities identified by the National Development Plan to achieve this by 2030, there exist several overarching priorities which South Africa needs first to resolve, to move forward as a viable nation.

Capitalism vs Communism

South Africa needs to pursue one ideology or the other. The National Development Plan, discussed later in this book, is in danger of derailing as influences within the African National Congress, continue to trumpet the National Democratic Revolution objectives. The NDR is a road to Socialism and ultimately Communism, a failed ideology. The National Development Plan prescribes capitalist principles adopted by more successful Western economies. It is significant today that the South African Communist Party and the Congress of South African Trade Unions have lately distanced themselves from the ANC under Jacob Zuma and his acolytes.

In December 2007, Polokwane witnessed the most important shift in South African politics since 1994. A coalition led by these two protagonists and others ousted Thabo Mbeki and his capitalistic GEAR policies and set the country on a socialistic NDR path.

Since then SACP members have been influential in both government and trade unions in steering South Africa on a socialist route. At its core, this agenda dictates ‘abolishment of individual property rights’.

The NDP conversely focusses on two cornerstones – education and employment.

During the Cold War, there was a contest for influence in Africa, between the US and Western powers on the one hand, and the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc countries on the other. Most of newly independent ex-colonies in Africa received military and economic support from one of the Superpowers.

Despite its racist policies, the South African government was supported by many governments in the West, particularly Britain and the USA. This was because the South African government was anti-communist. The British and American governments used political rhetoric and economic sanctions against apartheid, but continued to supply the South African regime with military expertise and hardware.

Impact of the collapse of the USSR on South Africa

This article was produced for South African History Online on March 22, 2011

There were many reasons why apartheid collapsed. But the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union was a major cause of the end of apartheid in South Africa.

Under apartheid, South Africa was a fascist state with a capitalist economy. The National Party was strongly anti-communist and said they were faced with a 'Rooi Gevaar' or a 'Red Threat'. The apartheid state used the label 'communist' to justify its repressive actions against anyone who disagreed with their policies.

The collapse of the USSR in 1989 meant that the National Party could no longer use communism as a justification for their oppression. The ANC could also no longer rely on the Soviet Union for economic and military support. By the end of the 1980s, the Soviet Union was in political and economic crisis, and it was increasingly difficult for the Soviet Government to justify spending money in Africa.

In 1989, President F.W de Klerk, the last apartheid Head of State, unbanned the African National Congress, the South African Communist Party and the Pan Africanist Congress.

He stated that the collapse of the Soviet Union was decisive in persuading him to take this step:

‘The collapse of the Soviet Union helped to remove our long-standing concern regarding the influence of the South African Communist Party within the ANC Alliance. By 1990 classic socialism had been thoroughly discredited throughout the world and was no longer a serious option, even for revolutionary parties like the ANC.

At about the same time, the ANC was reaching a similar conclusion that it could not achieve a revolutionary victory within the foreseeable future. The State of Emergency, declared by the South African Government in 1986, and the collapse of the Soviet Union - which had traditionally been one the ANC's main allies and suppliers - led the organisation to adopt a more realistic view of the balance of forces. It concluded that its interests could be best secured by accepting negotiations rather than by committing itself to a long and ruinous civil war.’

Quote source: www.fwdklerk.org.za

Creeping Communism in South Africa

Dave Steward

November 7, 2014

DOES THE NDP OFFER ANY PROTECTION AGAINST CREEPING COMMUNISM IN SOUTH AFRICA?

One hundred and sixty-six years ago, in 1848, Karl Marx wrote in the Communist Manifesto that "A spectre is haunting Europe. It is the spectre of communism".

During the last century communism brought economic devastation and totalitarian dictatorship wherever it was implemented and resulted in the deaths of over 50 million people.

Never in the history of mankind has any political system failed so dismally and brought such suffering to so many people in such a relatively short time.

And yet, unbelievably, the spectre of communism has returned to haunt us here in South Africa.

In 1928 Comintern - the international branch of Soviet Communism - instructed the SA Communist Party "to transform the ANC into a fighting nationalist organization" and to develop "systematically the leadership of the workers and the Communist Party in the organization."

The SACP has faithfully carried out this instruction. The leadership role that it has developed within the ANC has enabled it to play a central role in all the organization’s major ideological initiatives:

In 1956 leading members of the SACP drafted the ANC's core mobilization document The Freedom Charter.

The SACP once again took the lead in 1961 when it persuaded the ANC to embark on its armed struggle - against the wishes of the then President of the ANC, Chief Albert Luthuli.

The armed wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe, was throughout its existence under the effective control of the SACP.

In 1962 the SACP developed the concept of ‘colonialism of special type' - which presented a Marxist analysis of the political situation in South Africa. The CST analysis - even after 1994 - continues to regard white minority colonialism/capitalism as the cause of persistent black underdevelopment.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s virtually all the members of the ANC's National Executive Committee were also members of the SACP.

At the ANC's Morogoro Conference in 1969 the SACP once again took the lead by further developing the ideology of National Democratic Revolution (NDR).

In 2007, together with COSATU, the SACP helped anti-Mbeki elements to seize control of the ANC; to appoint Jacob Zuma as President of the ANC and subsequently to ‘recall' President Mbeki.

Together with COSATU, it took the lead in dispensing with President Mbeki's successful GEAR economic policies.

In 2012, the SACP played a leading role in formulating and introducing the "second radical phase of the NDR."

The NDR has become the ANC's guiding ideology and is the fountainhead of government policy. Incredibly, its central element is an ongoing struggle by the ANC-controlled state against white South Africans based on their race.

The central task of the NDR is "the resolution of the antagonistic contradictions between the oppressed majority and their oppressors; as well as the resolution of the national grievance arising from the colonial relations."

This involves "the elimination of apartheid property relations" through the redistribution of wealth, land and jobs from whites to blacks by means of affirmative action, BBBEE and land reform.

The final goal of the NDR is the establishment of the ‘National Democratic Society' that will be characterized by demographic representivity throughout government, society and the private sector in terms of ownership, management and employment.

A core element of NDR - from which the SACP derives its vanguard role - is its identification of workers as the main motive force of the ANC. Because the SACP claims to be the political leader of the workers it believes that it is endowed with a vanguard role in determining the direction and pace of the NDR. It is also important to note that COSATU - the other representative of the workers - gives its primary loyalty to the SACP - and not to the ANC.

In June 2011, COSATU President Sidumo Dlamini declared that

"We are a Marxist-Leninist formation not in words but through our commitment to the struggle for socialism and in that context, we encourage our members to fill the front ranks of the SACP and we subject ourselves to the discipline of communists."

This is even though a recent survey indicated that only 6% of COSATU members were also active members of the SACP.

Armed with this mandate the SACP has played a leading role in directing the NDR - except for the period between 1996 and 2007 - when the NDR was captured by what the SACP refers to as "the 1996 Class Project." This arose from the ANC's decision in 1996 to abandon the socialistic RDP and to adopt instead the more orthodox free-market GEAR programme. The GEAR policies under the guidance of Trevor Manuel achieved significant economic successes - including growth levels of over 5% in 2006 and 2007; a budget surplus and reduction of the national debt to only 22% of GDP.

However, the SACP and COSATU viewed GEAR as a betrayal of socialist principles. They feared that the NDR had been hijacked by capitalists who were intent on moving the revolution in a non-socialist direction. At its 9th Congress in 2006 COSATU decided to launch a battle for the ‘heart and soul' of the ANC at the organization’s National Conference at Polokwane at the end of 2007. It resolved, among other things, that

"...the working class must re-direct the NDR towards socialism and jealously guard it against opportunistic tendencies that are attempting to wrest it from achieving its logical conclusion, which is socialism;

this decade must be dedicated to a struggle to challenge and defeat the dominance of white monopoly capital, which reproduces itself through the emerging parasitic black capitalists; and that

we adopt an official position that rejects the separation of the NDR from socialism and asserts that the dictatorship of the proletariat is the only guarantee that there will be a transition from NDR to socialism."

In December 2007, this town - Polokwane - witnessed the most important shift in South African politics since 1994.

A coalition led by the SACP, COSATU and others opposed to President Mbeki, won the support of 60% of the delegates - and were thus able to seize control of the ANC. This gave them the power to dismiss any recalcitrant ANC MP from Parliament and de facto control of the legislative and executive branches of the state.

The new ANC leadership, in which the SACP and COSATU played an influential role, dictated who should be ‘deployed' to which leadership positions - and who should be ‘recalled'; which policies should be adopted by Parliament - and which should be set aside; and finally, who the President should be.

The success of the SACP and COSATU in overturning the 1996 Class Project and in securing once again primary influence over the direction of the NDR is of central relevance to the SACP's intention of taking over control of the state. In its view that "the central question of any revolution, including the South African NDR, is the question of state power."

A few years ago, the SACP appointed a commission to consider whether the Party should attempt to win state power by contesting national elections as a separate political party. The commission reported, with disarming frankness, that, "internationally, capitalist dominated societies are an extremely unfavorable electoral terrain for Communist Parties. There is not a single example of a Communist Party, on its own, winning national elections within a capitalist society - let alone using such a breakthrough as the platform to advance a socialist transformation."

The SACP reached the conclusion that "although elections are important, there is not a pre-determined singular route for the working class to hegemonize state power.'

The SACP realized that electoral politics might not be an essential path to state power because, without having to win a single vote, it was already being given approximately 30% of the ANC's parliamentary seats. Although SACP MPs are elected under the name of the ANC their party insists that its "cadres who are deployed as ANC elected representatives, or as public servants must continue to owe allegiance to the Party and cannot conduct themselves in ways that are contrary to the fundamental policies, principles and values of the SACP."

The other route to ‘hegemonizing' state power is through ‘entryism'. The Political Report of the SACP's 12th Congress in June 2007 quotes with approval the 1928 Comintern instruction to infiltrate the ANC and draws specific attention to the need for an entryist approach: "we repeat: ‘developing systematically the leadership of the workers and the Communist Party in this organization.'"

This approach is also in keeping with the SACP's "Medium Term Vision" "to secure working-class hegemony in the State in its diversity and in all other sites of power".

The SACP has made significant progress in securing key leadership positions within the ANC and the Alliance. It claims that since 1994 "tens of thousands of communists have taken up the challenges and responsibilities of governance." Members of its Central Committee now hold the following key posts - with strong influence within the Presidency and within ministries dealing with economic policy and property rights:

Gwede Mantashe: Secretary-General of the ANC (and recently described by Ferial Haffajee as "the most powerful man in South Africa".)

Jeff Radebe: Minister in the Presidency responsible for the NDP - and sometimes referred to as President Zuma's ‘Prime Minister';

Deputy Minister Buti Manamela: Deputy Minister in the Presidency

Rob Davies: Minister of Trade and Industry

Senzeni Zokwana: Minister of Agriculture

Minister Thembelani Noesi: Minister of Public Works

Jeremy Cronin: Deputy Minister of Public Works

Minister Blade Nzimande: Minister of Higher Education and Training

Godfrey Oliphant: Deputy Minister of Mineral Resources

Ebrahim Patel: Minister of Economic Affairs - although not a member of the Central Committee - strongly associated with COSATU.

Madala Masuku: Deputy Minister of Economic Development.

Sidumo Dlamini: President of COSATU.

Frans Baleni: General Secretary of the National Union of Mine Workers

Fikile Majola: General Secretary of NEHAWU

Many thousands of other SACP members - declared and undeclared - play key roles throughout the government and the public service and in the trade unions.

The SACP has also succeeded in steering the NDR in a direction that is more conducive to its view that elements of socialism can be introduced now - even before the final success of the NDR. As far as the SACP is concerned "advancing, deepening and defending the NDR will require an increasingly decisive advance toward socialism."

The SACP acknowledges that, since its success at Polokwane in displacing the 1996 Class Project, there has been a "considerable strengthening of the left's ideological positions on government economic and social policies and programs." Its successes have included the following "major paradigm shifts":

The adoption of the New Growth Path; The adoption of the Industrial Policy Action Programme; The multi-billion-rand multi-year state-led infrastructure programme; The rejection of willing-seller, willing-buyer approach to land reform; and A commitment to rolling out a National Health Insurance Scheme.

The SACP has been the main force behind the introduction of what is currently the ANC's core programme - the radical implementation of the second phase of the NDR. The idea of the "second transition" was first introduced by Jeff Radebe in March 2012. He said that changes in the balance of forces in South Africa and globally had opened the way for the ANC to dispense with some of the cumbersome constitutional compromises on which the "first transition" was based. He added that "our first transition embodied a framework and a national consensus that may have been appropriate for political emancipation, a political transition, but has proven inadequate and inappropriate for our social and economic transformation phase."

Manifestations of this radical second phase - and the process of building elements of socialism before the completion of the NDR - are included in the following laws and initiatives affecting property:

The cancellation of bilateral investment treaties with European countries;

Proposals that farmers should give 50% of their farms to farm workers;

The Promotion and Protection of Investments Bill;

The Property Valuation Act;

The Mineral and Petroleum Resources Bill;

The Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act;

The Regulation of Land Holdings Bill; and

The Private Security Amendment Bill.

Some of these bills can be traced back to decisions taken by the SACP at its 13th Congress last year. All of them promote the SACP's ultimate goal of eliminating or diluting private property rights - no doubt, in keeping with Karl Marx's dictum that "the theory of Communism may be summed up in one sentence: Abolish all private property".

There are, of course, powerful and influential individuals and groups within the ANC who are deeply concerned about the SACP's role. These elements - called "liberal constitutionalists" or "emerging parasitic black capitalists" by the SACP - tend to support the pragmatic National Development Plan and were instrumental in ensuring that it was endorsed by the ANC's National Conference in Mangaung in 2012.

The problem is that the NDP is irreconcilable with many aspects of the NDR - and particularly with the radical implementation of the second phase.

In a 2012 speech, FW de Klerk warned that South Africa was at a crossroads. He said that we could

"... either take the road to economic growth and social justice that is indicated by the National Development Plan - or we can take the "second phase" road toward the goals of the National Democratic Revolution."

He said that, although he did not agree with all its proposals, the National Development Plan presented a vision of a future South Africa that all reasonable people could share. He agreed specifically with the NDP's analysis that the two main priorities were education and unemployment.

He said that the other road led to the ‘second phase' of the ANC's NDR. He pointed out that the SACP was one of the main driving forces behind this radical new direction - but that it did not view the NDR as the final destination of the revolutionary process. On the contrary, it viewed it as the beginning of a new phase when the SACP - as the self-proclaimed vanguard of the working class - would take over leadership of the revolution which would culminate ultimately in the establishment of communism.

Since then the NDP has encountered serious problems - and vitriolic opposition from the SACP and COSATU. At the Alliance Summit on 1 September 2013 it was agreed that

"...a number of concerns with certain aspects of the NDP, including the economic chapter" that the SACP and COSATU had raised were "legitimate".

"...the work of the National Planning Commission needs now to be more effectively institutionalized and taken forward within the state";

The NDP is "not cast in stone, and needs to be adapted, where appropriate"; and

"...positive elements" (that accorded with the SACP's programme), "such as the need for a capable developmental state ... fighting corruption, and spatial transformation" should be accepted.

One of the central questions confronting South Africa today is the degree to which the NDP will be implemented - or whether it will, in accordance with the Alliance Summit's decisions, be diluted and adapted to meet the requirements of the SACP and COSATU. It is not reassuring that Jeff Radebe - one of the authors of the radical second phase - has been given responsibility within the Presidency for the implementation of the NDP.

Another question is what can be done to expose and counteract the SACP's programme to further hegemonize state power and to lead South Africa via the NDR to socialism and communism?

The SACP's Mid-Term Vision poses a serious threat to our democratic institutions. Our Constitution calls for "a multiparty system of democratic government, to ensure accountability, responsiveness and openness."

"Accountability, responsiveness and openness" require that parties should contest elections under their own names and on the basis of their own policies. It is unacceptable that parties - with clearly distinct identities, policies and ideologies - should insinuate themselves into Parliament and into power under the guise of other parties.

Voters have a right to know that when they vote for the ANC they are voting for an alliance in which the SACP and COSATU clearly plan to play the dominant role.

The SACP is asserting its vanguard role in leading the NDR and makes no secret of its intention to hegemonize state power and to establish a socialist - and ultimately - a communist state.

In his 2012 speech FW de Klerk asked what the role of traditional ANC members would be in such a dispensation? Will their fate be the same as non-communists who participated in the initial stages of the Russian, Vietnamese and Cuban revolutions? This is, no doubt, a question that is also occupying the thoughts of many non-communist ANC members.

However, these are issues that the SACP would prefer to conceal.

Gwede Mantashe - then Chairman of the SACP - acknowledged in his address to the 13th Congress that "we are fast losing our ability to make a positive contribution without claiming credit." He warned of the importance of not "claiming to have shaped the course of things"... "as opposed to being a mature Marxist/Leninist Party that can play a vanguard role without labelling it as such".

Clearly, the SACP wants to conceal its successes. How serious is the actual threat?

On the one hand, we should avoid paranoia.

There are many countervailing forces within the Alliance and within our broader society that would make it difficult for the SACP to achieve its objectives.

As the SACP's vanguard role becomes more obvious it is bound to alienate traditional ANC supporters;

The SACP's core support base in COSATU is now deeply disunited - with NUMSA having withdrawn its support from the ANC;

The Party's close identification with the embattled President Zuma is eroding its claim to revolutionary integrity and to being an opponent of corruption;

Communist ideas are thoroughly discredited and cannot stand up to a rational debate on what the SACP calls the ‘battlefield of ideas'.

On the other hand,

We would be foolish not to take seriously what the SACP says and writes about its political intentions. It openly plans to hegemonize state power and to establish a socialist and then, ultimately, a communist state.

We would be equally blind not to take note of the strong position that it has established within the government and the Alliance - and particularly within the Presidency and economic portfolios. There can be little doubt that it drives the ANC's core NDR ideology - including the radical