Read also: Furious property mogul Lew Geffen: “Ballot result tells world SA is rotten”

Where parties are split down the middle, party leaderships may try to resolve difficulties by suspending party directives and allowing a free vote (as during the Brexit referendum debate). On key issues, individual MPs who threaten to vote against their parties may be bribed by promises of bounty for their constituents or by compromises made to relevant policy proposals, although ultimately the threat of expulsion from the party lies in waiting.

Individual MPs may also be buoyed up by the honour that accrues to them if they are perceived to be standing their ground on matters of political or moral principle. They may earn the respect of their political opponents as much as the brick-bats of their party colleagues.

Challenge for the ANC

The variations, inconsistencies and flexibility built into modern party systems clearly stands as a challenge to the contemporary ANC mantra that MPs are slaves to their party’s requirements. Yet the ANC position is by no means without logic. It is indisputable that under South Africa’s electoral system, as it stands, MPs are elected as party representatives and not as individuals.

National-list proportional representation allows for no individuality of candidates. Voters do not have individual MPs. They simply vote for a party. Under this system MPs are allowed minimal scope for conscience.

But, ultimately, the ANC has no answer to the popular expectation that, when pressed on major issues, MPs should vote for what they think is right. They should vote against that which they think is wrong. They must be guided by their conscience rather than their pockets.

Voters seem to expect that when MPs refer to each other as ‘honourable’ that they should indeed embody ‘honour’. Yet equally, the public distaste for blatant political opportunism, as displayed during the floor-crossing episodes of yesteryear when minority party MPs jumped ship, mainly to join the ANC for personal and financial reasons, voters expect MPs to respect the outcomes of elections.

Discipline yes, but courage too

National Assembly of South Africa

Seemingly there is no consistent set of principles and practices which will satisfactorily resolve the tension between party demands and individual conscience. Yet what does become clear is that there is much more scope for flexibility, tolerance of dissent, and – yes – freedom of conscience in systems where MPs are directly responsible to constituents rather than, as in South Africa, they are wholly accountable to their parties.

Is this why the ANC so forthrightly rejected the recommendations of the Van Zyl Slabbert Commission on Electoral Reform? The commission recommended a mixed electoral system, whereby MPs would be elected on party platforms but from multi-member constituencies.

There is no escaping the necessity of party systems to get the job of government done. Voters understand the need for party discipline. Yet as the vote of no confidence also shows, they also want MPs to have the courage to rebel.

There is no escaping the necessity of party systems to get the job of government done. Voters understand the need for party discipline. Yet as the vote of no confidence also shows, they also want MPs to have the courage to rebel.

Social Exclusion

The provision of certain rights to all individuals and groups in society, such as employment, adequate housing, health care, education and training. This may be defined as social inclusion.

Social Inclusion and Policymaking in South Africa: A Conceptual Overview

Michael Cardo

Member of Parliament for the Democratic Alliance and the Deputy Shadow Minister in the Presidency. He is a graduate of the University of Natal (BA Hons) and the University of Cambridge (MPhil, PhD in History). Before being elected to Parliament, he served as the Director of Policy Research and Analysis in the Department of the Premier, Western Cape Government, where he was responsible for producing the government’s Social Policy Framework and strategy document on social inclusion.

“Social inclusion” has gained increasing currency in international and domestic policy discourse over the past decade, to some extent, replacing (albeit partially incorporating) once du jour ideas about “social cohesion” and “social capital”. South Africa’s supposed policy blueprint, the National Development Plan (NDP), is anchored in the concept of social inclusion. The NDP emphasises a capable state, a “capabilities” approach to development, and active citizenship and participation in the economic, civic and social norms that integrate society1. These are integral components of social inclusion. The NDP also underscores the need for redress measures in creating an inclusive, non-racial society in terms of Section 9 (2) of the Constitution, by broadening opportunities and pursuing substantive equality. This essay traces some of the recent key concepts in social policy discourse from “social cohesion” through “social capital” to “social exclusion” and “social inclusion”. While there is some degree of overlap between these terms, “social exclusion” and “social inclusion” are of greater analytical value. They provide a richer understanding of the link between access to opportunity and efforts to combat poverty on the one hand, and citizenship on the other. In concluding, I observe in passing the conceptual disjuncture between the approach adopted by the NDP on redress, development and social inclusion, and the African National Congress’s policy position on the “second transition” to a “national democratic society”.

Social Cohesion and Social Capital Before the popularisation of “social inclusion”, the allied concepts of social cohesion and social capital spawned a huge body of research and literature by organisations within the international policy community. Social cohesion is defined as a process or “set of factors that foster a basic equilibrium among individuals in a society”2. In 2004, the national Department of Arts and Culture (DAC), in South Africa, commissioned a study by the Human Sciences Research Council on the social “health of the nation”3. The HSRC employed social cohesion as a descriptive term to refer to “the extent to which a society is coherent, united and functional, providing an environment within which its citizens can flourish”.

It argued further:

Social cohesion is deemed to be present by the extent to which participants and observers of society find the lived existence of citizens to be relatively peaceful, gainfully employed, harmonious and free from deprivation. In 2012, DAC produced a “National Social Cohesion Strategy”4 that defines social cohesion as “the degree of social integration … in communities and society at large, and the extent to which mutual solidarity finds expression among individuals and communities”. This formed the basis for discussion at a “National Summit on Social Cohesion” in Kliptown in July 2012. Now, social cohesion is evidently a desirable objective, but harmonious societies or societies in equilibrium are not necessarily, by definition, inclusive societies – societies for all. For example, feudal societies may have been in equilibrium but they were certainly not inclusive. They did not recognise or give scope to the full, equal and active citizenship of all members of society. In contrast with social cohesion, definitions of social capital tend to focus on networks and relations of trust and reciprocity within these networks. Putnam defines social capital in terms of four features of communities: the existence of community networks; civic engagement or participation in community networks; a sense of community identity, solidarity and equality with other community members; and norms of trust and reciprocal help and support. There are various types of social capital. Bonding social capital refers to internal cohesion or connectedness within relatively homogenous groups, like families. Bridging social capital refers to the level and nature of contact and engagement between different communities, across racial, gendered, linguistic and class divides. Linking social capital refers to relations between individuals and groups in different social strata in a hierarchy where power, social status and wealth are accessed by different groups. Social cohesion and social capital have both been used by governments, nongovernmental organisations and inter-governmental organisations as conceptual tools for public policy.

The World Bank enthusiastically adopted social capital, which it defines with reference to social cohesion: Social capital refers to the institutions, relationships, and norms that shape the quality and quantity of a society’s social interactions. Increasing evidence shows that social cohesion is critical for societies to prosper economically and for development to be sustainable. Social capital is not just the sum of the institutions which underpin a society – it is the glue that holds them together. The World Bank concedes, however, that it is difficult to measure social capital. For example, feudal societies may have been in equilibrium but they were certainly not inclusive. They did not recognise or give scope to the full, equal and active citizenship of all members of society.

Furthermore, social capital is not necessarily desirable. Halpern8 suggests that organised criminals or gangs comprise a social network with shared norms but they do not constitute a societal good. Portes9 cites the downsides of social capital as the exclusion of outsiders, restriction on individual freedom and a downward levelling of norms. Like social capital, social cohesion is not a ready-made tool for public policy. It is vague. The slipperiness of the concept makes it difficult to translate social cohesion into a set of tangible strategic outcomes with measurable indicators. Towards a New Conceptual Framework One of the main drawbacks of social cohesion and social capital as conceptual and analytical tools, then, is their lack of rigour. Over the past 30 years, “social exclusion” and “social inclusion” have increasingly been used in the literature on social policy. Nevertheless, there is a close link between them and social cohesion and social capital. As Phillips argues: ‘there is a strong but complex relationship between social inclusion (mostly as an outcome but also as a process), social exclusion (mostly as a process but also as an outcome) and the social cohesiveness of societies’. Jones and Smyth11 argue that the concept of social exclusion deepens understandings of poverty and provides a conceptual link between access to opportunity and citizenship. Social exclusion broadens the conventional framework that posits poverty as a lack of resources relative to needs. In this way, it complements Peter Townsend’s seminal analysis of poverty in terms of relative deprivation and Amartya Sen’s notion of capability deprivation: the idea that citizens are excluded from society if they do not have the power, the opportunity or the means to lead a life they value, and thereby achieve substantive freedom. The ideas of agency and individual responsibility (alongside rights) are central to the discourse on social inclusion and citizenship. The “rights and responsibilities” of citizenship is a theme that suggests that social inclusion should be viewed as a fundamental right and ‘capability’, since being able to be included into society is a critical aspect of citizenship. What is Social Exclusion? In 1997, the UK government established a Social Exclusion Unit that defined social exclusion as ‘a shorthand label for what can happen when individuals or areas suffer from a combination of linked problems such as unemployment, poor skills, low incomes, poor housing, high crime environments, bad health and family breakdown’. Definitions of social exclusion may include all or some of the following elements: disadvantage experienced by individuals, households, spatial areas or population groups in relation to certain norms of social, economic or political activity; the Definitions of social exclusion may include all or some of the following elements: disadvantage experienced by individuals, households, spatial areas or population groups in relation to certain norms of social, economic or political activity; the social, economic and institutional processes through which disadvantage is produced; and the outcomes or consequences of those processes on individuals, groups or communities.

Poverty and social exclusion are driven up and down by demographic trends such as youth unemployment, lone parents, teenage mothers and immigration from other provinces.

social, economic and institutional processes through which disadvantage is produced; and the outcomes or consequences of those processes on individuals, groups or communities. The European Commission defines social exclusion as: The multiple and changing factors resulting in people being excluded from the normal exchanges, practices and rights of modern society. Poverty is one of the most obvious factors, but social exclusion also refers to inadequate rights in housing, education, health and access to services. It affects individuals and groups, particularly in urban and rural areas, who are in some way subject to discrimination or segregation; and it emphasises the weaknesses in the social infrastructure and the risk of allowing a two-tier society to become established by default. In sum, social exclusion is the involuntary exclusion of individuals and groups from society’s political, economic and societal processes, which prevents their full participation in society. Social exclusion is the denial (or non-realisation) of the different dimensions of citizenship – civic, economic, social and cultural – either through lack of access to opportunity or failure to use that opportunity. Such opportunities take the form of education, healthcare, housing, safety, and neighbourhoods that are linked physically (through transport and amenities) and socially (through social capital and trust).

Poverty and social exclusion are both a cause and effect of socially dysfunctional behaviours such as substance abuse, violent crime and domestic abuse. Poverty and social exclusion are driven up and down by demographic trends such as youth unemployment, lone parents, teenage mothers and in-migration from other provinces. Social Exclusion and Multidimensional Notions of Poverty Contemporary understandings of human development have stressed that a lack of economic resources is not the only determinant of poverty. Resources cannot be understood divorced from their social context. Poverty is increasingly being framed in terms of the capacity to participate in the society in which citizens live. In Europe, the term social exclusion originated in the social policy discourse of the French socialist governments of the 1980s and referred to a disparate group of people living on the margins of society – especially those without access to the system of social insurance. However, the European Commission has argued for a more multidimensional understanding of the ‘nature of the mechanisms whereby individuals and groups are excluded from taking part in the social exchanges, from the component practices and rights of social integration’. Alongside economic resources and employment, health, education, affordable access to other public services such as justice, housing, civil rights, security, well-being, information and communications, mobility, social and political participation, leisure and culture also need to be considered. This provides for a multidimensional portfolio of indicators on social exclusion. Globally, a multidimensional approach to poverty and social inclusion has long underpinned efforts to promote development. The foreword to the first Human Development Report set out the position in 1990: The purpose of development is to offer people more options. One of their options is access to income – not as an end but to acquiring human wellbeing. But there are other options as well, including long life, knowledge, political freedom, personal security, community participation and guaranteed Human Rights. People cannot be reduced to single dimension as economic creatures. Five years later, the Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development and the Programme Action of the World Summit for Social Development highlighted the various manifestations of poverty: Poverty has various manifestations, including lack of income and productive resources sufficient to ensure sustainable livelihoods; hunger and malnutrition; ill health; limited or lack of access to education and other basic services; increased morbidity and mortality from illness; homelessness and inadequate housing; unsafe environment; and social discrimination and exclusion. It is also characterized by a lack of participation in decision-making and in civil, social and cultural life”

The World Development Report was entitled “Attacking Poverty”, and in his foreword to the Report (p.v), the then President of the World Bank, James Wolfensohn, referred to ‘the now established view of poverty as encompassing not only low income and consumption but also low achievement in education, health, nutrition, and other areas of human development’. The World Development Report opened by referring to “poverty’s many dimensions” and stressed that these went beyond hunger, lack of shelter, ill health, illiteracy and lack of education. The poor, it said, ‘are often treated badly by the institutions of state and society and excluded from voice and power in those institutions’ From Social Exclusion to Social Inclusion There is no consensus in the literature that social inclusion and exclusion are two ends of a continuum or that they are binary opposites, even though much of the literature tacitly assumes this. Steinert distinguishes between integration and participation as potential opposites to exclusion. He rejects integration (which he equates with ‘inclusion’) as being too passive and normative. In a similar vein, Barry notes that highly socially integrated societies can be marked by large inequalities of power and status. Walker and Wigfield contrast inclusion and exclusion as follows: If social exclusion is the denial (or non-realisation) of different dimensions of citizenship then the other side of the coin, social inclusion, is the degree to the poor, it said, ‘are often treated badly by the institutions of state and society and excluded from voice and power in those institutions’ which such citizenship is realised. Formally we might define social inclusion as the degree to which people are and feel integrated in the different relationships, organisations, sub-systems and structures that constitute everyday life. As a process, then, social inclusion refers both to integration into social, economic and civic life and the pursuit of active citizenship as well to counter poverty understood in the sense of capability deprivation. An inclusive society is a society for all, in which every individual – each with rights and responsibilities – feels he or she has an active role to play, thus reducing the risk of social dysfunction and disintegration. Social Inclusion and Redress the NDP’s overriding goal is to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality through a virtuous cycle of economic growth and development. To do this, it advocates a new approach to policy – one that moves from “a passive citizenry receiving services from the state” to one that “systematically includes the socially and economically excluded”, where people are “active champions of their own development”, and where government works to “develop people’s capabilities to lead the lives they desire”.

Generally, then, the NDP is anchored in the concept of social inclusion. Its vision is of an inclusive non-racial society as described in the preamble to – and founding provisions of – the South African Constitution. Specifically, Chapter 1531, on “Transforming society and uniting the country” deals with “promoting economic and social inclusion, … active citizenry and… the crafting of a social compact”. This chapter departs from the premise that a “capabilities” approach to development is “critical to broadening opportunities, an essential element of the nation-building process”. It elaborates: South Africa needs to build a more equitable society where opportunity is not defined by race, gender, class or religion. This would mean building people’s capabilities through access to quality education, health care and basic services, as well as enabling access to employment, and transforming ownership patterns of the economy. Redress measures that seek to correct imbalances of the past should be strengthened. Yet it is instructive to note that the NDP is critical of the way in which some of the existing models of redress have been implemented – the Employment Equity Act, which the NDP notes “does not encourage the appointment of people without the requisite qualifications, experience or competence”.

The NDP underscores the fact that race and gender need to be considered alongside qualifications and experience, and that skills- and staff-development should be at the centre of employment equity plans. On other redress measures such as black economic empowerment and land South Africa needs to build a more equitable society where opportunity is not defined by race, gender, class or religion. This would mean building people’s capabilities through access to quality education, health care and basic services, as well as enabling access to employment, and transforming ownership patterns of the economy.

Reform, the NDP stresses that they should be rooted in the letter and spirit of Section 9 (2) of the Constitution. They should promote growth or jobs to support the NDP’s overarching goals. They should not enforce rigid quotas or the mechanical application of numerical formulae. And they should focus on broadening opportunities as opposed to manipulating outcomes.

Outcomes must be linked to opportunity, effort and ability because an inclusive society in which citizens have developed their capabilities is a society in which opportunities are not granted as special favours to selected beneficiaries. This truly “developmental” approach to redress, anchored as it is in the concept of social inclusion, is a far cry from the ANC’s so-called “second transition” to a “national democratic society”. The ruling party placed a renewed emphasis on the “second transition” at its policy conference in 2012, based on its analysis of the “national democratic revolution”.

With its misguided emphasis on strengthening the role of the state in the economy and its prioritisation of existing flawed models of racial redress (all of which manipulate outcomes rather than extend opportunities), the “second transition” totally controverts the Constitution, the NDP, the capabilities approach to development, and the concept of social inclusion.

It is often said that South Africa is the most unequal society in the world. Business and Economy Editor Andile Makholwa put a few questions to Haroon Bhorat, Professor of Economics and Director of the Development Policy Research Unit at the University of Cape Town.

How unequal is South Africa society?

Is it true that South Africa is the most unequal society in the world?

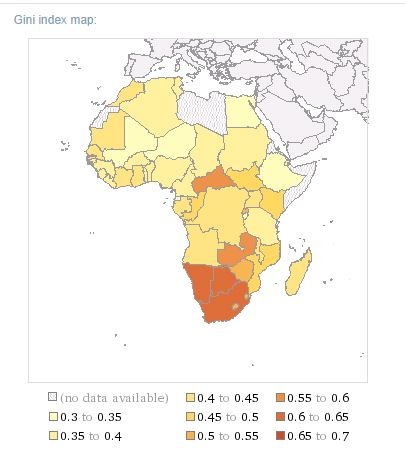

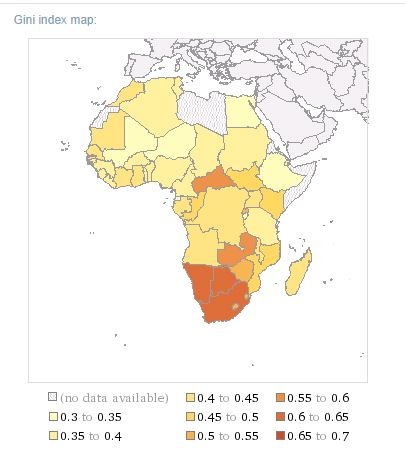

Depending on the variable used to measure inequality, the time period, and the dataset, South Africa’s Gini coefficient ranges from about 0.660 to 0.696. The Gini coefficient is the measure of income inequality, ranging from 0 to 1. 0 is a perfectly equal society and a value of 1 represents a perfectly unequal society.

This would make South Africa one of the most consistently unequal countries in the world. I say “consistently” because you may find a Gini of say 0.7 for a country that has had only one survey in the last 20 years. This is not a consistent measure. Or you may find a society that has undergone civil war.

Why is inequality so pronounced in South Africa?

There is a myriad of reasons, but some of the key factors include skewed initial endowments (or assets that people and households have) post-1994 in the form of, for example, human capital, access to financial capital, and ownership patterns. These, and other endowments, served to generate a highly unequal growth trajectory, ensuring that those households with these higher levels of endowments gained from the little economic growth there was.

In addition, we are an economy characterized by a growth path which is both skills-intensive and capital-intensive, thus not generating a sufficient quantum of low-wage jobs – which is key to both reducing unemployment and inequality.

What can be done about it? Is there anything the political economist Thomas Piketty can teach us?

Piketty’s thesis in part argues that schooling is critical for reducing inequality in the long-run. Human capital accumulation is one possible mechanism through which to overcome a growth path where the rate of return on capital ® exceeds the rate of economic growth (g) – r>g.

To generate a more equal growth path, thus equalizing r and g, it is argued that the schooling and educational pipeline plays a potentially crucial role in an economy’s long-run growth trajectory.

|

|

Footnote

In the Summa Theologiae, Medieval Theologian Thomas Aquinas said of Greed: ‘it is a sin directly against one's neighbor, since one man cannot over-abound in external riches, without another man lacking them... it is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, inasmuch as man contemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things.’

Earth provides enough to satisfy every man's needs, but not every man's greed.

|

Mahatma Gandhi

Greed, Inc: Making millions off the country’s poorest

David Care

10 Dec 2014

David Carel is currently a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University. He researches South African social policy with a focus on basic education and the social grant system.

South Africa recently accomplished one of the greatest feats of financial inclusion in the history of the region – and few people batted an eye. In just 18 months, the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) opened more than 10 million new bank accounts for grant recipients, incorporating an unprecedented share of the nation’s poor into the formal banking system. Yet behind this well-intentioned effort lies serious abuse. The company overseeing the distribution of grants has heavily exploited its position, undermining the welfare of grant recipients that the state is meant to protect.

Cash Paymaster Services (CPS), a subsidiary of the financial services behemoth Net1 and winner of the tender to distribute R10 billion in SASSA grants each month, undertook a mass re-registration of all 16 million beneficiaries between March 2012 and August 2013. By opening bank accounts for grant recipients in this process, South Africa surpassed the National Development Plan’s target of 70% financial inclusion by 2013. The new system was heralded to reduce grant fraud, cut distribution costs and improve accessibility for recipients.

But the contract stood on questionable ground from the start. Central features of the tender procedure had been changed days before submission, all but excluding most bidders. The bank chosen for the accounts was Grindrod Bank, a subsidiary of a freight logistics and shipping services provider with virtually no branches accessible to grant recipients. To make matters worse, last year the United States department of justice investigated Net1 for violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, citing falsification of financial reporting. In November 2013, the Constitutional Court declared the awarding of the tender to CPS to be “constitutionally invalid”, though it was left in place out of fear of disrupting the grant system.

All along, behind the scenes of this legal and political debacle, grant recipients have suffered.

Net1 and its multitude of subsidiaries have leveraged their access to grant recipients to market their own products. SASSA recipients, expecting a simple grant to help make ends meet, are bombarded with offers for micro-loans, insurance packages and airtime advances. In dire straits, countless recipients capitulate, and the consequences are dismal; loans have been found to include up to 100% annual interest and service fees can quickly accumulate to over 50% of the principal. Though SASSA has attempted to intervene, recent reports suggest that these offerings have continued. Many recipients, who live hand-to-mouth, find themselves heavily indebted to the very corporation that was chosen to help the government provide for their welfare.

Recipients have been subjected to a range of other deductions as well. When their bank accounts were opened in the re-registration process, they were inadvertently tied to a national debt registry. As a result, outstanding debts that they had incurred in prior years, such as for house furniture they had not fully repaid, suddenly began to be deducted straight from their SASSA bank accounts. While one could argue that the companies have a right to collect on these debts, it is not the role of the state, and certainly not in its social security arm, to force this to happen. The integration of recipients into the open banking economy without protection has channelled millions of rands directly to corporations.

Moreover, these factors have severe

There is no escaping the necessity of party systems to get the job of government done. Voters understand the need for party discipline. Yet as the vote of no confidence also shows, they also want MPs to have the courage to rebel.

There is no escaping the necessity of party systems to get the job of government done. Voters understand the need for party discipline. Yet as the vote of no confidence also shows, they also want MPs to have the courage to rebel.