Chapter 8

Learn How Great Stories Lead To Great Conversation.

Stories offer a progression of ideas that momentarily allow the listener to follow along on a journey, taking them away from the world, their worries or problems, and lifting them into another time and place. From the earliest days of our childhood we learn to enjoy stories. They draw us in, capture our imagination, and make us feel involved in the narrated events. Stories are shared through a myriad of mediums, such as movies, games (especially video games), books, and conversations; often shared and handed down from one person to another, or from generation to generation.

When we listen to stories we naturally allow ourselves to relax and slowly drift into a semi-conscious state of mind. If we listen long enough, we may begin to immerse ourselves into the story. As a speaker, you will notice when your listener’s reach this state as their shoulders will drop and their eyes may begin to stare deeply into space. It is here that the listener will be most easily influenced, as the consciousness offers little resistance to suggestion.

Stories Types

You can choose different types of stories in order to achieve different results. Consider first the outcome that you wish to attain and secondly, the audience that you will be telling your story to. There are essentially six types of stories from which all other forms of story-telling stem from. They are:

Myths

Myths are legendary stories. They may have originally been created by ancient folk to explain the unexplainable such as life, death, the creation of the universe, and possibly even the supernatural. Myths are mostly based on imagination (or so it would seem) as there is no proof to these types of stories usually involving some form of imaginary characters or creatures. Examples may include heroes, dragons, unicorns, elves, monsters, fairies, gods, etc.

Sagas

The word ‘saga’ was originally used for any story featuring heroic deeds of a medieval Norwegian hero. Gradually, it came to mean a long eventful narrative about a family, social group, or dynasty with several chapters, cantos, or even volumes. A saga has several legends of heroes added to it and these heroes may be real or half-real (exaggerated truths)As they tend to be based on (at least partially) some real story or event.

Fables

A fable is a short story that teaches a moral point using animals and plants that act human. Acting human could consist of talking (a human language), walking like humans (upright), and other things of that nature. Fables provide lessons and guidance that are very practical and useful in everyday life and thus should be acknowledged for the moral point they provide.

Parables

A parable is a short story that teaches a moral point. It describes a setting, explains the action that occurs there, and highlights the results. The Bible is full of parables along with other religious texts.

Folklore

Folklore are the tales and stories handed down orally from generation to generation, and any real documentation of the tale no longer exists. They generally depict the emotional states (such as hopes and fears) of ordinary people (usually in the local area). Almost every social group has its own folklore traditions and beliefs

Fairytales

Fairytales are usually magical stories of some type of fantasy characters such as dwarves, elves, fairies, giants, gnomes, goblins, mermaids, trolls, or witches. Children tend to enjoy fairy-tales very much because of enchantment and magical power such stories hold.

Preempting The Story

You want to draw the listener into your story before the story begins. You want to have their full attention. By the time you start your story, you want to have begun mesmerizing them, pulling them into another world where the restrictions that they create and the walls they build no longer exist. You want to create an atmosphere where they can feel at ease, engaged, and relaxed. To do this, we preempt the story with phrases that let the listener know we are about to tell them a story, and since most conversational stories are about some past event, preemptive phrases will most often begin with some reference to the past. The following is a short list of such phrases that are recognized as story starters:

1) Let me tell you a story about…

2) Let me tell you a story…

“Let me tell you a story about the time I had to learn the toughest lesson of my life…”

3) Would you like to hear a story about…?

“Would you like to hear a story about the most dangerous adventure anybody’s ever had? It all began with…”

4) It was…

“It was only 2 years ago when I was in a very similar situation…”

5) Once…

“Once, I had all he courage in the world but now…”

6) There was a time…

“There was a time I thought I had all the answers…”

7) A long time ago…

“A long time ago, I was searching for answers to…”

8) When I was….

“When I was 17, I learned a very important lesson. I was in the middle of great tragedy when…”

9) I had a friend once…

“I had a friend once, who told me the secret to life itself…”

10) …But before I tell about that, let me tell you about…

“I want to tell you how to improve our performance in just once step but before I tell you that, let me tell you about a time when I was learning to cope with…”

Not only can the above examples be combined;

“It was… Once… Along time ago… When I was young… I had a friend who…”

But they can also be applied with variations:

“a long time ago” could be altered to “long long ago”

“I had a friend once” could be altered to “I knew someone once”.

Story Structure

People prefer to receive information in a structured and organized way which helps them follow along, and stories are no different. Through the years, story tellers have developed generalizations of structure designed to make story telling easier. Some of these have divided story-telling into two separate acts, 3-acts, 4-acts, 5-acts and onwards all the way to 22 acts or more! Here, the goal is to provide story-structure that can easily be utilized within general conversation, and so we will stick to the 3-act, 4-act and 5e-act structure:

3-Act Story

The 3-Act story outlines a beginning, middle, and end. It is probably the simplest story structure.

1) Separation: In this part either characters are separated from each other (usually with the main character leaving home), or objects are separated from their owners. In psychoanalysis, we split off uncomfortable, bad objects, often projecting them onto others. In rites of passage, the person leaves their community often symbolically wearing different clothes or markings. In business change, the targets are unfrozen from their current position, readying them for change.

2) Transition: This is often the main part of the story but lasts longer than the climax in a 5-Act structure. The main character (and often other characters) go through some type of change, transition or alteration, usually in the form of trials or hardships.

3) Reintegration: In this part, life returns back to the way it was, often keeping the changes that have occurred in the transition of the story. Characters that have left home may return now return or objects are returned to their rightful owner making things ‘normal’ again.

* You may consider adding trigger events that help the story take a turn. For example:

You may add a trigger event that helps the story move from separation to transition and another trigger event that helps the story move into the reintegration phase.

# NOTE: The 3-act structure is best used when you want to provide short stories that are quick and powerful (lasting anywhere from 3 seconds to 3 minutes). They are best used with parables, stories of past experience (yours or someone else’s), and stories of future predictions.

4-Act Story

There have been many variations on the four-act structure, but the basic essentials are as follows:

1) The Set-up: This phase sets the stage and introduces the key elements of the story.

2) The Problem: A problem is introduced that must be resolved.

3) Deepening the Problem: The state of the problem is amplified so that it becomes a major issue.

4) The Solution/Resolution: A solution is provided that resolves the problem.

The 5 Act Story Structure

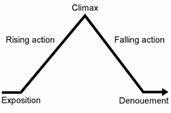

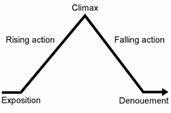

Also known as Freytag’s pyramid, the 5-Act story structure organizes stories into five developmental sections.They are:

1) Introduction: Often referred to as the exposition. Here, any background information needed to properly understand the story is revealed to the audience.

2) Rising Action: The story becomes a little more complicated as dangers or conflicts are introduced. Often, this is made more interesting when a primary conflict is then complicated by the introduction of a secondary conflict.

3) Climax: The climax is the point of the story that is meant to peak the audience’s interests the most. It is the part where all the action happens, often as a major turning point for the characters.

4) Falling Action: This is for the characters to resolve any remaining items that may still need closure. The main part of the story has thus concluded and the story is headed toward the end. This may often contain a moment of final suspense where the final outcome of the conflict is still in doubt.

5) Dénouement, Resolution, or Catastrophe: This is the final ending of the story where any conflicts or tensions have been resolved and the characters usually return to a ‘normal’ life. In a dénouement, the characters are set to be better off than they were at the beginning of the story; in a catastrophe, the characters are set to be worse off than they were previously (often the death of several main characters). A resolution simply returns life back to normal (most times).

# NOTE: The five-act story structure is best suited situations where there is a little more time for a more vivid story (3 minutes or more), and may be used with myths, fables, folk-tales and fairy-tales. If you have the listener’s attention, and there is time to spare, you will gain a deeper sense of rapport and build a more emotional involvement with the 5-act story structure.

Literary Devices – Storytelling Techniques

Story techniques are used to make a story more interesting. The following is a list of common storytelling techniques:

Narrative Hooks:

A narrative hook is a section at the beginning of the story that gets the reader or audience aroused and interested, thus wanting to continue engaging in the story.

“Have you ever wondered why you can’t get what you want in life? Listen up, and we’ll discuss the 8 things you MUST do to achieve personal success!”

The Aside

The aside is when you steps outside of the story itself and speaks directly to the listener. For example:

If the story is about you, then during the story you may create a short break in the story itself and speak directly to the listener, returning to finish the story afterwards.

“Just yesterday I spent Christmas with my nieces and nephews, and it dawned on me how different life is today… [Aside begins] Back when I was a child there was the children spent more time playing together in the outdoors, today, technology controls the minds of our youths [Aside ends]”

Backstory

A story is often told without completely disclosing the background that led to the events of the story itself. This can leave the listener without a full understanding of the narrative, so in order to rectify this, the background may be told prior to the story itself or possibly even within the story (essentially creating a break within the story). It is also possibly to divide backstories into several parts or mini-sections that are told in relevant sections of the story itself.

“The reason George is like that is because when he was young his father use to scold him a lot for things that were out of his control… Over many years he has lost his sense of self-worth”

Chekhov’s Gun

This is the introduction of something (anything) early in the story whose meaning is left unclear until later on. Anton Chekhov, a German physician and author (also considered to be one of the greatest short story writers in history), once said:

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it's not going to be fired, it shouldn't be hanging there.”

“As we walked down the halls at school at 9pm, the school had just been cleaned by the janitor. It was so clean that not a single spec of dirt was noticeable, except a yellow banana peel lying on the ground, probably part of the janitor’s lunch. … … … [later in the story] Sure, we were wrong to try to hack the school’s computer to change our grades, and found ourselves running from security down the hall. I had forgotten about the yellow banana peel on the ground… As my foot hit the banana peel I went flying into the air”

The Cliffhanger

The cliffhanger is a story ending that is designed to leave the listener in trapped in suspense. Essentially, this occurs when the ending of the story is in fact unfinished or left to the imagination of the listener. In conversation, this is sure to cause a sense of desire in the listener to know more about the ending, and he will surely ask question, which in turns gets him involved in more conversation.

“It was almost over, and certain that we had gotten a passing grade, we handed our assignments to the teacher and awaited her review!” [used as an ending to the story].

Discovery

This occurs when a character of the story realizes something that was previously unknown, causing the story to take a sudden turn or twist.

“I didn’t want to do it… Just the thought of speaking in public frightened me… My anxiety got anxiety. But without choice I stumbled to the front of the stage and fought to force my eyes open. I struggled to start the first sentence. I started moving my body vigorously with every phrase. And you know what I found… They loved me… I had captured the audience like no other presenter could. Even more importantly, I loved it too.”

Exposition

Exposition is a short introduction of the story that brings the listener up to speed on the current situation to where the story actually begins. It may also be used mid-story to speed up the story itself, leaving out insignificant details.

“In order to understand why the following events were so important to me, you must first understand the state of economy in my home town… We were poor folks with little money, shabby homes, and no future.”

Flashbacks

The flashback (also called an analysis) is used to interrupt the normal development of the story to bring the listener back in time for a short moment. It can also be used to bring clarification to the main part of the story by informing the listener of past events in the lives of the character(s) within the story. The flashback can also be used to connect together events that are related, but yet separated in time.

"As every living moment I had was spent studying the fine art of communication, I remembered how lazy I was in school, how I refrained from studying or doing homework in those days… Ahhh, if only I’d been more studious then, maybe things would be easier now.”

Flash-forward

The natural progression of the story is temporarily interrupted and the listener is brought forward in time for a short period, returning to the main story shortly. It is usually used to show future probabilities or possibilities, or otherwise to purvey plausible cause and effects of what may happen if the character in the story does certain things.

”These skills will help you become a better communicator, so that you can get what you want out of lif… Can you imagine it now: Negotiating for that raise in pay; swaying beautiful women; building better relationships.”

Fold

This occurs when the story suddenly takes a different direction. In effect, the story begins once again from the current situation. This usually has the effect of leaving the listener guessing what will happen next.

“I was walking through Chinatown, when I noticed a man looking at me strangely, I looked away and noticed another man was also staring at me. It’s as if I was in the place at the wrong time… And before I knew it, a massive parade broke out on that street, with dancing lions and firecrackers, and lots of performers.”

Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is when we leave clues or indications about what will happen later in the story. The goal is to give the listener pieces that don’t quite fit together while still hinting at the plausible importance of those pieces. This technique is often used more than once in a connected stream of foreshadowing called ‘multiple foreshadowing’. There are several ways of foreshadowing events, such as: The use of flash-forward as foreshadowing; mention of worry, apprehension or heightened concern earlier in the story; predictions; or symbolism.

“I thought my troubles over, but a little voice inside my head had mentioned that the worst is yet to come…”

In Medias Res

This literally means “in the middle of things”. It is the act of beginning the story in the middle of where it is logical to start the story from. This allows the audience to dive right into a story and gets them to wonder ‘what happened’ previously.

“It happened to me last week… Bam!!! Just like that. I was in a situation that I knew I couldn’t handle. The crowd was asking me questions I didn’t have answers to. The only way I could get out of it was by passing the buck on to someone else”

The MacGuffin

The McGuffin is an object, event, or thing that appears to be the central focus at first but is actually unimportant to the story as a whole. It is often used to introduce another situation or otherwise to introduce characters or objects.

“I crept into the room, and noticed a coffee table. On the coffee table was a newspaper, a wine glass, and a paper clip. I searched book shelf for the secret book, and when I finally found the book, it had a small lock holding shut. I realized I could use the paper clip to open the lock”