Chapter 7

Communicate Effectively With Difficult Communicators

This book was not written to provide a course on human behavior; however, there is something to be said about being able to adequately communicate with difficult individuals to achieve a fair outcome. In this chapter, we discuss different types of behavior and review how to hold conversations with individuals who display such behaviors – note that there are many different ways to deal with many different behaviors, here, we discuss only those that promote a healthy conversation aimed at furthering the relationship.

Understanding Behavior

There are some considerations to keep in mind when working with difficult people. First, it is important to understand that all behavior is learned and adaptive. Everything we do as humans is shaped by our experience. When we find something does not work, we discard of it; alternatively, when we find something does work, we use it and may even turn it into a habit. Some of these habits may carry on from childhood to adulthood, or may even become a part of our identity- who we are.

Situational Indifference

To make things a little more complicated, we often fail to differentiate between one context and another. So the same behavior may be used in any situation that has some remote similarity to the original situation in which the behavior was learned.

Behavioral Meaning

All human behavior whether consciously or unconsciously, carries meaning. We act in a certain way because of the meaning that such actions hold (I do this because that is what respectable people do), or because of the outcomes associated with our actions (If I do this, it means that will happen). Such meaning may incorporate our goals, beliefs, judgments, values, morals, ethics, and so on.

Self-Benefit

Aside from meaning, all actions are performed for purpose of benefiting the person acting. Even difficult people act the way they do because, in some shape or form, they feel they will benefit from doing so. The only question is: what type of benefit is it exactly that they are seeking? Some seek a sense of power, some search for a release for their frustrations, some seek to find or avoid consequences, and some people just want to be heard.

Self-Benefit & Positive Intent

If the principle of self-benefit tells us that every action is performed for the purpose of benefiting the person acting in some way; that means that the intent behind every action must have (or have originally had) some positive purpose – this is called positive intent. By first looking for the positive intent behind any action, we can better seek to both define and correct the action. For example, aggressive behavior is most often initiated because of an underlying need for protection (often, protecting beliefs, morals and values), or the need to right some wrong (something that was done to the aggressor that caused him to become aggressive). This being said, if we understand why someone is aggressive, for example, we can then find better ways to deal with their anger or frustrations.

The Golden Rules of Conflict

In all situations involving difficult people, there are a series of restraints that must be applied for proper resolution to occur. These restraints aid in moving the conversation toward a mutual understanding, and apply to all situations, although perhaps for differing reasons:

Self-Control

When working with difficult people, whether they are forceful, aggressive, passive-aggressive, or simply over-emotional, the first step is always to maintain your own self-control. This is not to say that there should be no portrayal of emotion, but any emotion that you portray should be planned and performed consciously, as opposed to being a natural state. If you think you will be working with difficult people often, I strongly suggest that you engage in both anger-management courses as well as theatrical courses (which will also help you in the art of persuasion). Along with self-control, you must also hold a great degree of patience. Without patience, you cannot maintain your own self-control.

Objectivity

As you work at keeping your self-control, it is important that you recognize that as you engage in conversation with difficult people, you are in fact placing yourself into a momentary situation of discomfort. That’s all it is- a momentary situation of discomfort. Once the conversation comes to a close, the situation will be over with, and you will need to get on with the remainder of your day without letting that situation effect you. At lease, this is how professional conversationalists view such situations.

That being said, difficult conversations should always be viewed as objectively as possible. Remove your own emotions from the situation, and try to understand the entirety of the situation, what is happening, what has happened, what will happen, what is being said, and how the conversation effects all people involved (and you may not be the only two people affected by the outcome of the conversation). Remember that most people will react to you in the same manner that you act toward them.

Understanding

As you practice self-control and patience with an objective view of the situation, it is very important to try to understand each situation from the point of view of the other person. Step into their shoes, if you will. In order to do this you must take as much into account as possible: What you know about their history, their personality under ordinary circumstances, and if / how the current situation may have affected them. By “putting yourself in their shoes” so to speak, it may give you a better understanding of the source of the difficulty. This is, of course, not to say that all behavior is made acceptable by understanding past events, but rather that such an overall understanding can better your ability to resolve the issues at hand, and may even put your own anger or frustration at ease.

Eye-Contact

Frequent eye contact is an important part of communication, and this is especially true when working with difficult people. Eye contact says a few things about you. It suggests you hold a high level of confidence and a sense of dominance. It also suggests that you are listening attentively and are fully engaged in the conversation. A lack of eye contact could suggest the exact opposite. Look away from time to time as you don’t want to stare at others which may be perceived as confrontational, but always for a reason (this is where some of those theatrical classes may come into play)… Look away because you’re thinking , because you’re feeling empathy, because you’re remembering, but never look away without a reason – Doing so, suggests that you are losing your position on the topic, your sense of confidence or dominance.

Open-Posture

While this book is not designed to be about body language, I find it extremely important to review the importance of open body posture when working with difficult people. Non-verbal communication is said to compose approximately 55% percent of all messages. People are always making judgments. We do this in our quest for meaning – and where better to associate meaning than in communication or conversation. Open body posture is a sign of openness to communicate and understand; while closed body posture is a sign of distancing yourself, whether that be a refusal to be open-minded and understanding or simply not listening at all.

When we refer to open body posture, we mean not only your main posture (openness of the arms and legs), but also keeping an open stance (don’t try to block the other person in), openness of the hands (don’t make fists or closed hands), keeping an erect spine and head held at mid-level.

Active Listening

Active listening is an important part of all communication. Active listening means listening actively to what is said, and the meaning behind what is said, and disregarding unimportant distractions

Types of Difficult Behavior

As we discuss the different types of difficult behavior, we will make reference to methods in which they are difficult in verbal conversation. Note, however, that people who portray these difficult behaviors verbally are also likely to portray the same behaviors physically, so some caution must be taken in dealing with these types of behaviors to ensure your own level of safety.

It must also be noted, that behaviors can occur from situational factors or they can be rooted in personality. For example: One may become aggressive momentarily as a result of some situational trigger; or one may be aggressive as a trait of their personality (and thus display aggressive behavior most of the time). Whenever possible, it is important to differentiate which of the two you are dealing with, as this may alter your overall approach.

1) The Aggressive: Aggressive behavior causes or threatens physical or emotional harm to others. There are two types of aggressive individuals. There are those who have learned, possibly from the early days of childhood, to be (or to act) aggressive upon others. This is an emotional disorder referred to as “dispositional aggression” (or “dispositional anger”). These people have been conditioned to believe that circumstances must occur in accordance with their desired outcomes in order to avoid varying forms of personal loss (i.e. loss of finance, loss of time, loss of opportunity, loss of self-respect, etc.). This conditioning may have occurred as a first-hand experience or it may have been learned through family, peers, and social structure or otherwise. Aggression may also be caused by the inability to deal with one’s own emotions.

It is because they have been conditioned by such beliefs that they are more difficult to work with, and may be viewed as pushy or even as bullies. Aggressive individuals tend to enjoy being in power, even if their aggressiveness is only temporary. They prefer to be in control, usually seeking to be respected – Even if by fear, and will prey on those who appear weaker than they are. As they recognize their power over an individual, they may begin to feel superior and will re-assert their aggressiveness over that individual under future circumstances. On the other hand, aggressive individuals recognize and respect strong character on an equal level, as long as they are not being overpowered.

There are also those who become aggressive as their emotions are triggered by external circumstance – This could be a particular situation, or it could be something that was done or said [see also “Expectation Violation” in chapter 2]. These are generally short-lived or temporary instances of aggression, and do not reflect the individuals natural personality. People who become aggressive by such triggers usually feel that they are protecting their rights, beliefs or values, and are willing to do anything to do so. They are most often focused on themselves and the violations that have (according to their own perception) been inflicted upon them and lose the capacity to monitor their actions. This violation triggers high-levels of emotional dissonance, and the aggressor results in behavior that is designed to resolve that dissonance – Such a resolution often means forcing the anger outward externally.

In 1988 a management expert by the name of Robert M. Bramson (Ph. D.) identified three uniquely different types of aggressive people:

a) The Sherman Tank: These are the directly aggressive people who come on strong and forceful. They send direct attacks of criticism and arguments. This may be because of a strong sense of righteousness if they feel they have been abused in some way, because they need to prove themselves right (and in turn devalue the rights of others), or because of a strong belief that making others look bad makes them look good.

# NOTE: Refrain from showing any signs of fear as this will only serve to confirm their sense of power. Refrain from reciprocating the aggressive behavior, as this will only cause a battle for power, and may result in physical violence. Also, don’t use commanding words or sentences. If the aggression is only verbal, allow the aggressor to exert his emotion, and remain calm and unemotional, actively listening to the underlying issue. They may need some time to calm down before they begin to speak with sense and rationality. When the aggressor allows a moment of pause, assert yourself mildly, showing respect, and move the conversation toward the future tense with emphasis on cooperation.

b) The Sniper: These are aggressive people who do not directly attack you, but send indirect attacks through the conversation, in the form of “pot-shots”, innuendos, teasing or hurtful remarks. Often, these people will combine their hidden aggression with some form of playful act - You may often leave the conversation wondering “what did he mean by that?” They may hold the belief that by making others look bad it makes them look good.

# NOTE: Begin by identifying the behavior aloud, preferably in a one-on-one session (doing so publicly may cause further retaliation and turn them into a Sherman Tank. Follow this by inquiring about the (real) reasoning behind their behavior. Make apologies if necessary, and seek mutual agreement on ways to rectify the cause and prevent future hostility.

# NOTE: Sometimes people act this way purely for a sense of power, as previously mentioned – making themselves look good by making others look bad. Under such situations, you may consider using light humor as a response. This may diffuse their actions and prevent future actions as they realize that their show of power has no effect over you.

c) The Exploder: These are people who seem perfectly fine until finally they explode. These fits often occur as a result of negative emotions that have been held-back or kept under control for a period time, or opinions that have not been previously stated. It is possible that such negative emotions stem from outside influences, and something in the conversation triggers an emotional release. Exploders are more likely to release their emotions where they feel someone will listen, or under circumstances where they no longer care about the consequences of doing so.

# NOTE: Exploders need a few moments to express their anger, but their anger will subside fairly quickly. Often, they just want to be heard, and they don’t care by whom. During this emotional phase, they will undoubtedly tell you about the cause of their anger. Once their emotion begins to subside, interrupt respectively, and speak in terms of cooperativeness (apologizing if necessary), changing their frame of mind toward future outcome. Keep their focus on the future and continue to promote cooperativeness if possible.

2) The Passive-Aggressive: Passive aggressive behavior occurs when people are passive in direct communication, but become aggressive in indirect communication. This type of behavior rarely occurs as a result of situational factors, and is usually rooted in one’s personality. These are the people who won’t say anything to you, but become angry and often exert their anger elsewhere – Possibly by assaulting non-animate objects, or by expressing their anger to other people. In direct communication, the passive aggressive may make indirect statements such as sarcasm, being critical of what is being said, or simply being silent.

Passive aggressive behavior is usually the direct result of some level of anger or frustration combined with the fear of direct conflict. The fear of conflict may result from the fear of the unknown, meaning not knowing how the other person will act; or it could be from a lack of faith in one’s own abilities to effectively handle conflictive situations (especially if one wishes to sustain the current nature of the relationship).

# NOTE: Begin all relationships with a sense of openness – Let others know that they can always talk to you about anything. If you notice someone is being passive-aggressive in response to your communication, they may feel over-powered by you. Get them to open up to you – Begin by talking with a softer tone of voice, let them know that you do care, and that effective communication is necessary for the relationship to flourish. Get them to talk about their anger calmly (and not act out their anger with additional frustration). Cooperatively seek a resolution.

Passive aggressive individuals often look for others who allow them to exert their anger. This may either be someone who is weaker or more subdominant than themselves – who makes them feel powerful; or it may be someone who will simply listen to their frustrations.

# NOTE: If you are on the receiving end in conversation with a passive aggressive individual, begin by openly identifying their behavior for what it is – anger / hostility. Show empathy and understanding, yet establish limitations of behavior – Let them know that they cannot take their aggression out on you. Get them to talk about the specifics of the issue at hand. Get them to suggest better ways of dealing with their issue, and then motivate them to take action on those suggestions.

3) The Passive: Passive behavior does not further a healthy relationship. It puts one person in a dominant role while the other person remains passive, and feels they have not release for their emotions. Like the passive-aggressive, this behavior does not commonly occur due to situational factors, and is usually a result of personality. Passiveness is often displayed by consistently agreeable behavior, or through silent behavior.

Passive individuals may suffer from some form of depression or low-self-esteem, which in turn develops into a fear of direct confrontation (even if that confrontation is minimal). If they do not have some emotional outlet for their frustration or anger, it may build up and develop into an explosive outburst (see “the exploder” above).

# NOTE: Much like the passive-aggressive, it is important to promote a sense of cooperation and openness. Speak to passive individuals with a softer tone of voice so that they do not feel overpowered. Use much patience in getting them to disclose their emotions

4) The Assertive: Assertive behavior is a step down from aggressive. Assertive individuals are dominant and forceful, this behavior usually results from some sense of righteousness – They either believe that they are right in their stance on some topic of discussion, or that they have been wronged in some way and are attempting to make things right. Assertive people are very confident, in their directness. It is crucial to handle assertive behavior correctly without allowing it to proceed to the next step – Aggression.

# NOTE: Assertive people often need to let out their frustration, so listen to what they are saying and do not provide immediate feedback (or they will feel as if you are not “really” listening). When they stop, or pause for a lengthy period, provide them with empathy for their feelings and for the situation that has frustrated them. Use apologies if warranted. Redirect their focus to possible resolutions, and ask questions that engage logical functions such as “What do you think…” or “How can we resolve…”. Use language that promotes cooperation and fairness.

5) The Negativist: Any negative behavior that is repetitive exists for a reason. People aren’t just born negative, it is a choice (although, sometimes an unconscious one). Sometimes, the negativity is an emotional barrier meant to protect them from the world; sometimes, it’s a condition. They may be quick to suggest how you should behave according to their view of the world. Negativists can be recognized by the following:

a) Negative misinterpretations – They often interpret much of what is said in a negative point of view. For example: “You look great today” could be interpreted as “You mean I didn’t look good yesterday… What was wrong?”

b) A sense of powerlessness – Negativists often feels that that they cannot change things, and there is no sense in trying.

c) Pessimism – A belief that the future is desolate or dismal, and no matter how hard they try, the future will remain desolate or dismal, and “that’s just the way it is.”

d) Risk Aversion – Negativists usually refrain from situations that they view as risky or uncertain. To a negativist, anything may be viewed as risky, for example: They may be reluctant to share information about themselves that could later be used against them. They may also be quick to suggest what they feel is risky, for instance “Don’t swim in deep water because you may drown” or “Don’t spend your money on university, you won’t get a good job in this economy anyway.”

# NOTE: Try to limit the amount of time that you connect with negative people, but when you have to, remember that just like everybody else, negative people want to be understood – Letting them know you understand them may not only strengthen the friendship but may help change their attitude (to some degree).

# NOTE: Don’t allow their negativity to be focused, so learn to change topics of conversation with them quickly. Dissipate negative comments by objectifying them (removing the personal aspect) and by generalizing them (possibly by the use of universal quantifiers – all, every, always, never, etc.). Thus when a negative person says “This restaurant is expensive” you reply “all restaurants are expensive”.

6) The Chronic Complainer: The chronic complainer is a negativist of a different breed. They see everything that is wrong with their world, but usually don’t realize that their behavior is negative. Many of them even see themselves as “realists”, or even “perceptively positive” (and they may actually be positive individuals by nature). These individuals may have learned early that this behavior is likely to get them what they want; or it could be that they had (at one point) no other way to release their disapprovals or frustrations. In either case, the behavior has stemmed from their early life and carried on to adulthood.

Their complaints are usually real, at least to them. The real reason, however, that they complain, is to get attention, sympathy or validation / acknowledgement for their feelings. They identify themselves as victims in an unfair or unfortunate world, and often use phrases such as “Things never change”, or “Why does this keep happening to me?”

# NOTE: Begin by acknowledging what they are complaining about, and show empathy for their feelings. Any attempt to get them to see the positive side of things will result in a loss in rapport. Instead, after acknowledging their feelings, simply try to change the subject to some other topic. If they continue complaining about the same topic, offer suggestions, but keep those suggestions short and to the point. You may also consider asking questions directed at a change, such as “So what do about that?” or “Is there a way change that?”

7) The Know-It All: Know-it-alls are often fueled by their own sense of intelligence, and usually carry some genuine sense of superiority or grandiosity. They also tend to hold a bias of perception known as Curse of Knowledge (see chapter 3).

These individuals may have some deep sense of insecurity, in which they feel they must display their intelligence to gain the approval of others. It is this same sense of insecurity that often leads to problems in developing close relationships, in specific, a difficulty with intimacy on any level (even amongst friends). In other cases, know-it-alls may even provoke arguments, often beginning out of a sense of “fun” in order to prove their superior intelligence.

# NOTE: Since they seek attention, give them some of the attention that they desire. Listen to what they have to say when it is relevant to the conversation. When it seems that they are going off course with unwarranted information, bring them back to the topic at hand by use of questions (a good question to ask is “How is that relevant to our discussion?”).

Defensive Communication

We are all hard-wired to move toward those things that cause us pleasure, and away from those things that cause us pain or discomfort. As such, we often develop communication habits that are designed to protect us from pain or displeasure. As a child, having done something wrong, when asked about it we may lie and say “Wasn’t me, I don’t know who did it!” because we learned that being guilty of doing wrong means being punished. As adults, we tend to learn rather different strategies.

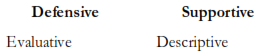

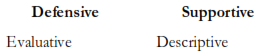

In 1999 Dr. Jack Gibb PhD. A former President of the Association for Humanistic Psychology, and a member of the American Board of Professional Psychology, developed a concept of defensive and supportive communication he called the Gibb Categories. In this, he outlines the recognizable differences between communication whose aim is to be defensive in nature, and communication aimed at being supportive of other individuals in the group (this also applies to one-to-one communication).

Gibb describes a pair of six types of communicative behavior, each pair being polar opposites. On the left, he lists defensive communicative climate; and on the right, he lists the supportive communicative climate - Behaviors that strive to be supportive in nature. These are as follows:

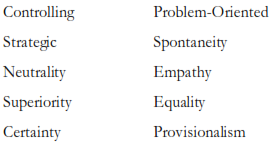

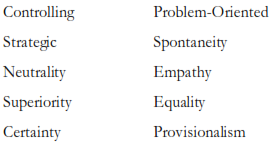

Evaluative / Descriptive

Evaluative communication is that of finding blame or fault; seeking judgments about things, events or people; or attempts to decipher why something has happened.

Descriptive communication occurs from seeking answers to “what” and “how”, as oppose to “why” and “who” Instead of asking questions like “who did that?” [Evaluative], we seek to find out “what happened”, “how did that happen?” or “how can we prevent that from happening again?” [Descriptive].

Controlling / Problem-Oriented

Controlling behavior is that of attempting to manipulate others into performing particular tasks or acting a certain way. This essentially suggests that the listener is, in some way, inadequate.

Rather that portray a controlling behavior, the supportive communicator will display a problem-oriented attitude, using solution-oriented language.

Strategic / Spontaneity

Gibb’s notion of strategic communication is that of carefully choosing one’s words and/or withholding information so as leave out information that may be used against oneself. This type of communication gives the impression that we have something to hide, or something that we do not wish to reveal.

# NOTE: On the other hand, when a person speaks in a spontaneous manner, it conveys openness and freedom to speak whatever is on one’s mind.

Neutrality / Empathy

Neutral communication shows a lack of interest in the listener and his concerns. When a listener hears this type of communication he is likely to become defensive, possibly perceiving this type of speech as personal rejection.

The opposite of neutrality would be a show of empathy for the feelings of others, also conveys a degree of personal respect. When we show that we understand the other person, combined with empathy, and a lack of desire to change the other person or alter their thinking, is most supportive.

Superiority / Equality

Communication of superiority is a show or a fight for power. It results in the “us vs. them” attitude. This may cause feelings of inadequacy in the listener, and if the listener cannot display his own assertiveness, may result in feelings of unimportance or possibly inferiority. A person who displays superiority is telling others that he is not willing share ideas, and does not desire feedback.

When a communicator uses words that suggest equality, both people can easily share ideas with an understanding that their differences such as status, power and wealth, worth, etc. are not important.

Certainty / Provisionalism

Certainty communication is displayed by a lack of open-mindedness. It is the “my way or the highway” attitude that results from a belief of superiority in some way. Much like the above comments on superiority, this type of communicative attitude makes the listener feel unimportant or inferiority

A person who displays provisional attitudes is willing to investigate possibilities openly.

Defense Mechanisms

In addition to behavior, attitudes, and personality, are situational communicative habits. Of these, it may be worth a moment to take a look at defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms are habitual behaviors that are rooted deep within the unconscious, that help defend against situations of conflict or discomfort. When we know something will be uncomfortable to deal with, we use these behaviors to deal with it. The following are a list of defense mechanisms most relevant to conversation:

Avoidance

This is just what the name implies. When we fear a person or situation may cause us discomfort, we may avoid it in order to prevent the discomfort. The problem with avoidance is that the issue never gets dealt with, and may become worse as time goes on. This is especially important in the development of relationships, where a small matter not dealt with today, could cost the entire relationship tomorrow.

# NOTE: Since people who use avoidance are acting on some form of fear or anxiety of encountering situations they don’t feel they can handle, reassure them that things will be alright, and use cooperative language such as “let’s”, “we”, “together”, etc. The same applies even if you are the target of the avoidant behavior.

Denial

Denial occurs when we refuse to accept or acknowledge something that is uncomfortable to us. The object of our discomfor