CHAPTER XXII

A MORNING IN PARIS

I SHALL never forget my first morning in Paris—the morning that I woke up after about two hours’ sleep or less, prepared to put in a hard day at sight-seeing because Barfleur had a program which must be adhered to, and because he could only be with me until Monday, when he had to return. It was a bright day, fortunately, a little hazy and chill, but agreeable. I looked out of the window of my very comfortable room on the fifth floor which gave out on a balcony overhanging the Rue St. Honoré, and watched the crowd of French people below coming to shop or to work. It would be hard to say what makes the difference between a crowd of Englishmen and a crowd of Frenchmen, but there is a difference. It struck me that these French men and women walked faster and that their every movement was more spirited than either that of the English or the Americans. They looked more like Americans, though, than like the English; and they were much more cheerful than either, chatting and talking as they came. I was interested to see whether I could make the maid understand that I wanted coffee and rolls without talking French, but the wants of American travelers are an old story to French maids; and no sooner did I say café and make the sign of drinking from a cup than she said, “Oh, oui, oui, oui—oh, oui, oui, oui!” and disappeared. Presently the coffee was brought me—and rolls and butter and hot milk; and I ate my breakfast as I dressed.

About nine o’clock Barfleur arrived with his program. I was to walk in the Tuileries—which is close at hand—while he got a shave. We were to go for a walk in the Rue de Rivoli as far as a certain bootmaker’s, who was to make me a pair of shoes for the Riviera. Then we were to visit a haberdasher’s or two; and after that go straight about the work of sight-seeing—visiting the old bookstalls on the Seine, the churches of St. Étienne-du-Mont, Notre-Dame, Sainte-Chapelle, stopping at Foyot’s for lunch; and thereafter regulating our conduct by the wishes of several guests who were to appear—Miss N. and Mr. McG., two neo-impressionist artists, and a certain Mme. de B., who would not mind showing me around Paris if I cared for her company.

We started off quite briskly, and my first adventure in Paris led me straight to the gardens of the Tuileries, lying west of the Louvre. If any one wanted a proper introduction to Paris, I should recommend this above all others. Such a noble piece of gardening as this is the best testimony France has to offer of its taste, discrimination, and sense of the magnificent. I should say, on mature thought, that we shall never have anything like it in America. We have not the same lightness of fancy. And, besides, the Tuileries represents a classic period. I recall walking in here and being struck at once with the magnificent proportions of it all—the breadth and stately lengths of its walks, the utter wonder and charm of its statuary—snow-white marble nudes standing out on the green grass and marking the circles, squares and paths of its entire length. No such charm and beauty could be attained in America because we would not permit the public use of the nude in this fashion. Only the fancy of a monarch could create a realm such as this; and the Tuileries and the Place du Carrousel and the Place de la Concorde and the whole stretch of lovely tree-lined walks and drives that lead to the Arc de Triomphe and give into the Bois de Boulogne speak loudly of a noble fancy untrammeled by the dictates of an inartistic public opinion. I was astonished to find how much of the heart of Paris is devoted to public usage in this manner. It corresponds, in theory at least, to the space devoted to Central Park in New York—but this is so much more beautiful, or at least it is so much more in accord with the spirit of Paris. These splendid walks, devoted solely to the idling pedestrian, and set with a hundred sculptural fancies in marble, show the gay, pleasure-loving character of the life which created them. The grand monarchs of France knew what beauty was, and they had the courage and the taste to fulfil their desires. I got just an inkling of it all in the fifteen minutes that I walked here in the morning sun, waiting for Barfleur to get his shave.

From here we went to a Paris florist’s where Madame pinned bright boutonnières on our coats, and thence to the bootmaker’s where Madame again assisted her husband in the conduct of his business. Everywhere I went in Paris I was struck by this charming unity in the conduct of business between husband and wife and son and daughter. We talk much about the economic independence of women in America. It seems to me that the French have solved it in the only way that it can be solved. Madame helps her husband in his business and they make a success of it together. Monsieur Galoyer took the measurements for my shoes, but Madame entered them in a book; and to me the shop was fifty times as charming for her presence. She was pleasingly dressed, and the shop looked as though it had experienced the tasteful touches of a woman’s hand. It was clean and bright and smart, and smacked of good housekeeping; and this was equally true of bookstalls, haberdashers’ shops, art-stores, coffee-rooms, and places of public sale generally. Wherever Madame was, and she looked nice, there was a nice store; and Monsieur looked as fat and contented as could reasonably be expected under the circumstances.

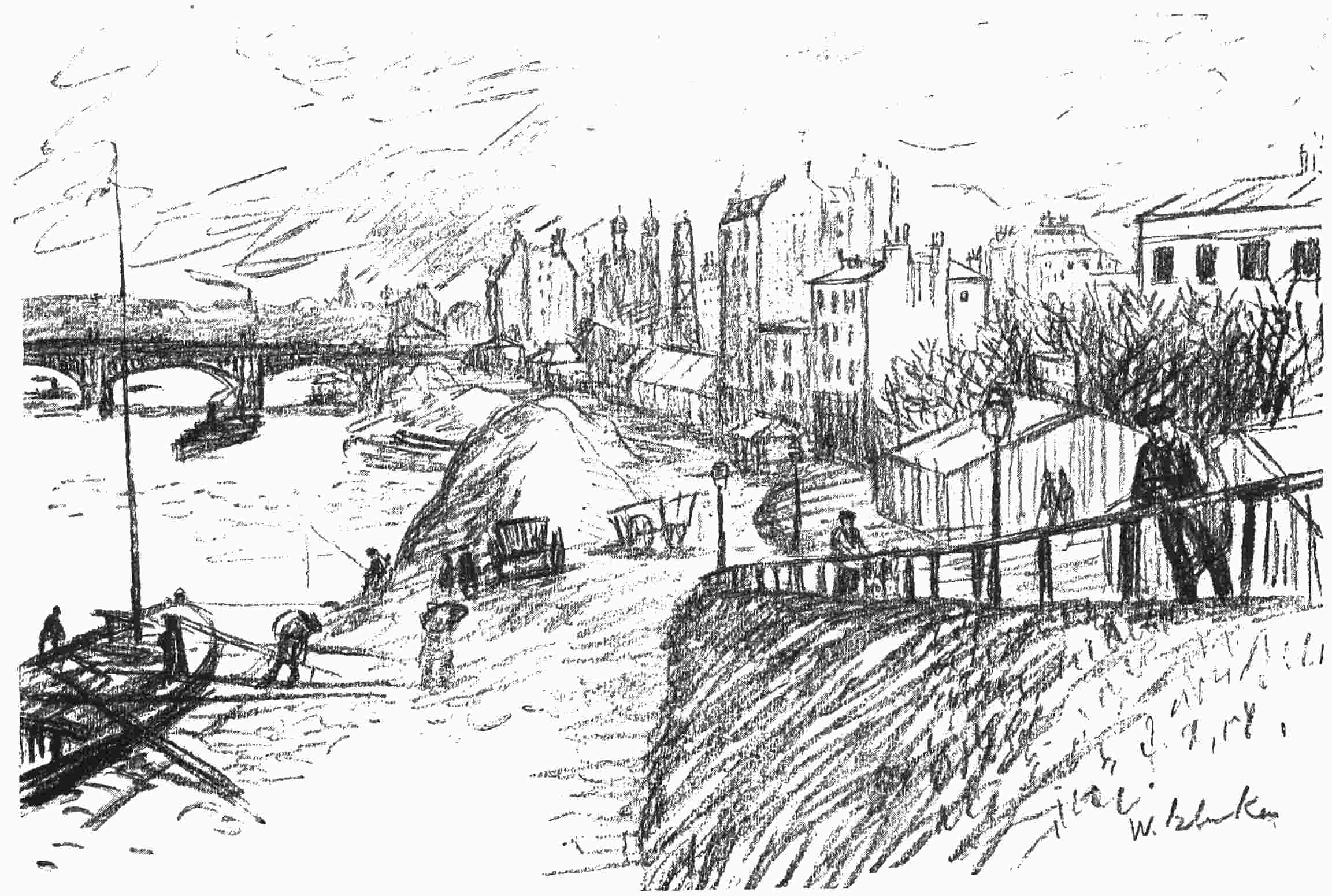

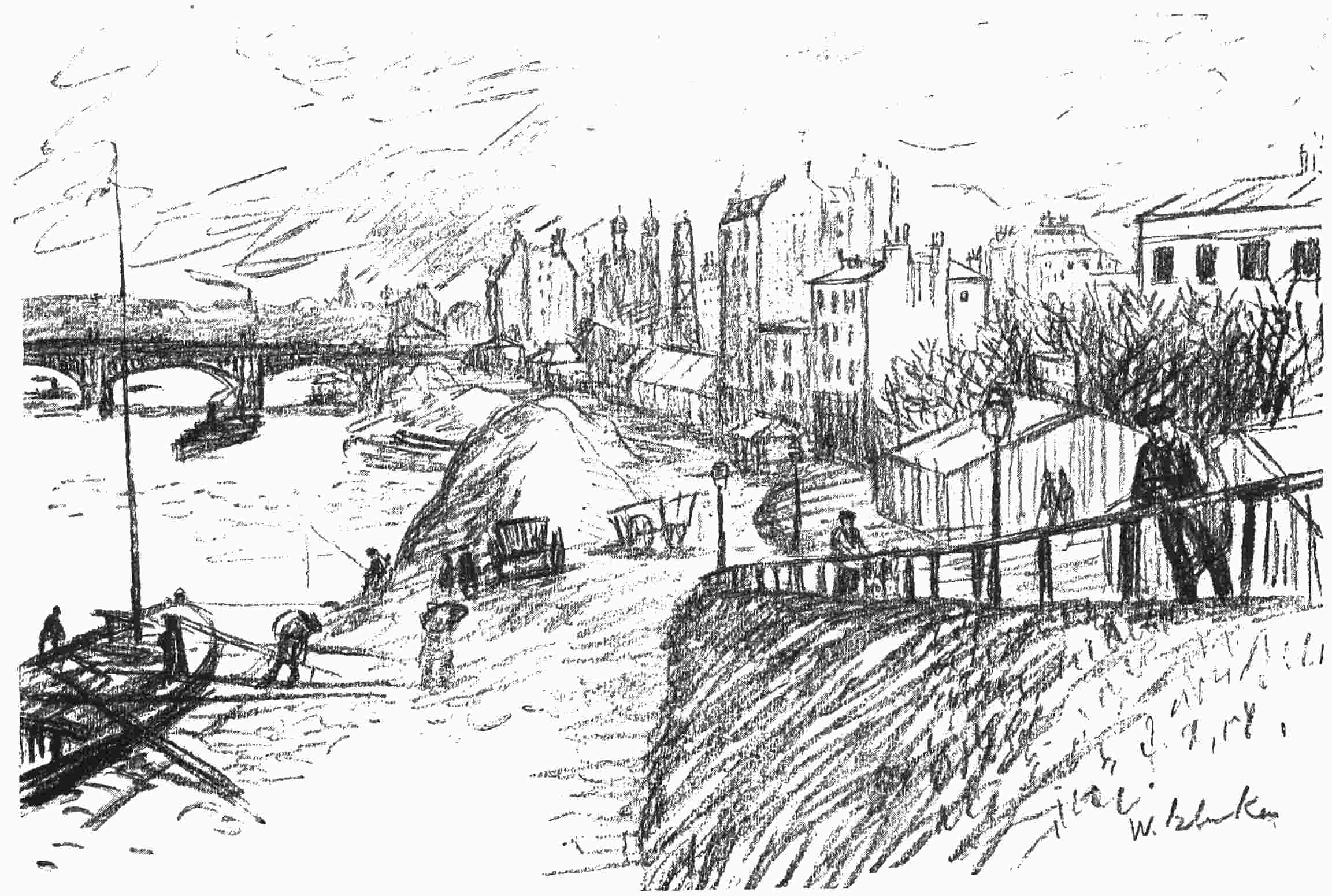

The French have made much of the Seine

From Galoyer’s we struck forth to Paris proper, its most interesting features, and I recall now with delight how fresh and trig and spick it all seemed. Paris has an air, a presence, from the poorest quarter of the Charenton district to the perfections of the Bois and the region about the Arc de Triomphe. It chanced that the day was bright and I saw the Seine, as bright as new buttons glimmering over the stones of its shallow banks and racing madly. If not a majestic stream it is at least a gay and dashing one—quick-tempered, rapid-flowing, artistically walled, crossed by a score of handsome bridges, and ornamented in every possible way. How much the French have made of so little in the way of a river! It is not very wide—about one-half as wide as the Thames at Blackfriars Bridge and not so wide as the Harlem River which makes Manhattan an island. I followed it from city wall to city wall one day, from Charenton to Issy, and found every inch of it delightful. I was never tired of looking at the wine barges near Charenton; the little bathing pavilions and passenger boats in the vicinity of the Louvre; the brick-barges, hay-barges, coal-barges and Heaven knows what else plying between the city’s heart and points downstream past Issy. It gave me the impression of being one of the brightest, cleanest rivers in the world—a river on a holiday. I saw it once at Issy at what is known in Paris as the “green hour”—which is five o’clock—when the sun was going down and a deep palpable fragrance wafted from a vast manufactory of perfume filled the air. Men were poling boats of hay and laborers in their great wide-bottomed corduroy trousers, blue shirts and inimitable French caps, were trudging homewards, and I felt as though the world had nothing to offer Paris which it did not already have—even the joy of simple labor amid great beauty. I could have settled in a small house in Issy and worked as a laborer in a perfume factory, carrying my dinner pail with me every morning, with a right good-will—or such was the mood of the moment.

This morning, on our way to St.-Étienne-du-Mont and the cathedral, we examined the bookstalls along the Seine and tried to recall off-hand the interesting comment that had been made on them by great authors and travelers. My poor wit brought back only the references of Balzac; but Barfleur was livelier with thoughts from Rousseau to George Moore. They have a magnificent literary history; but it is only because they are on the banks of the Seine, in the center of this whirling pageant of life, that they are so delighted. To enjoy them one has to be in an idle mood and love out-of-doors; for they consist of a dusty row of four-legged boxes with lids coming quite to your chest in height, and reminding one of those high-legged counting-tables at which clerks sit on tall stools making entries in their ledgers. These boxes are old and paintless and weather-beaten; and at night the very dusty-looking keepers, who from early morning until dark have had their shabby-backed wares spread out where dust and sunlight and wind and rain can attack them, pack them in the body of the box on which they are lying and close the lid. You can always see an idler or two here—perhaps many idlers—between the Quai d’Orsay and the Quai Voltaire.

We made our way through the Rue Mazarin and Rue de l’Ancienne Comédie into that region which surrounds the École de Medecin and the Luxembourg. In his enthusiastic way Barfleur tried to indicate to me that I was in the most historic section of the left bank of the Seine, where were St.-Étienne-du-Mont, the Panthéon, the Sorbonne, the Luxembourg, the École des Beaux-Arts and the Latin Quarter. We came for a little way into the Boulevard St.-Michel, and there I saw my first artists in velvet suits, long hair, and broad-brimmed hats; but I was told that they were poseurs—the kind of artist who is so by profession, not by accomplishment. They were poetic-looking youths—the two that I saw swinging along together—with pale faces and slim hands. I was informed that the type had almost entirely disappeared and that the art student of to-day prefers to be distinctly inconspicuous. From what I saw of them later I can confirm this; for the schools which I visited revealed a type of boy and girl who, while being romantic enough, in all conscience, were nevertheless inconspicuously dressed and very simple and off-hand in their manner. I visited this region later with artists who had made a name for themselves in the radical world, and with students who were hoping to make a name for themselves—sitting in their cafés, examining their studios, and sensing the atmosphere of their streets and public amusements. There is an art atmosphere, strong and clear, compounded of romance, emotion, desire, love of beauty and determination of purpose, which is thrilling to experience—even vicariously.

Paris is as young in its mood as any city in the world. It is as wildly enthusiastic as a child. I noticed here, this morning, the strange fact of old battered-looking fellows singing to themselves, which I never noticed anywhere else in this world. Age sits lightly on the Parisian, I am sure; and youth is a mad fantasy, an exciting realm of romantic dreams. The Parisian—from the keeper of a market-stall to the prince of the money world, or of art—wants to live gaily, briskly, laughingly, and he will not let the necessity of earning his living deny him. I felt it in the churches, the depots, the department stores, the theaters, the restaurants, the streets—a wild, keen desire for life with the blood and the body to back it up. It must be in the soil and the air, for Paris sings. It is like poison in the veins, and I felt myself growing positively giddy with enthusiasm. I believe that for the first six months Paris would be a disease from which one would suffer greatly and recover slowly. After that you would settle down to live the life you found there in contentment and with delight; but you would not be in so much danger of wrecking your very mortal body and your uncertainly immortal soul.

I was interested in this neighborhood, as we hurried through and away from it to the Ile-de-la-Cité and Notre-Dame, as being not only a center for art strugglers of the Latin Quarter, but also for students of the Sorbonne. I was told that there were thousands upon thousands of them from various countries—eight thousand from Russia alone. How they live my informant did not seem to know, except that in the main they lived very badly. Baths, clean linen, and three meals a day, according to him, were not at all common; and in the majority of instances they starve their way through, going back to their native countries to take up the practice of law, medicine, politics and other professions. After Oxford and the American universities, this region and the Sorbonne itself, I found anything but attractive.

The church of St.-Étienne-du-Mont is as fine as possible, a type of the kind of architecture which is no type and ought to have a new name—modern would be as good as any. It has a creamish-gray effect, exceedingly ornate, with all the artificery of a jewel box.

The Panthéon seemed strangely bare to me, large and spacious but cold. The men who are not there as much as the men who are, made it seem somewhat unrepresentative to me as a national mausoleum. It is hard to make a national burying-ground that will appeal to all.

Notre-Dame after Canterbury and Amiens seems a little heavy but as contrasted with St. Paul’s in London and anything existing in America, it seemed strangely wonderful. I could not help thinking of Hugo’s novel and of St. Louis and Napoleon and the French Revolution in connection with it. It is so heavy and somber and so sadly great. The Hôtel Dieu, the Palais de Justice, Sainte-Chapelle and the Pont-Saint-Michel all in the same neighborhood interested me much, particularly Sainte-Chapelle—to me one of the most charming exteriors and interiors I saw in Paris. It is exquisite—this chapel which was once the scene of the private prayers of a king. This whole neighborhood somehow—from the bookstalls to Sainte-Chapelle suggested Balzac and Hugo and the flavor of this world as they presented it, was in my mind.

And now there was luncheon at Foyot’s, a little restaurant near the Luxembourg and the Musée de Cluny, where the wise in the matter of food love to dine and where, as usual, Barfleur was at his best. The French, while discarding show in many instances entirely, and allowing their restaurant chambers to look as though they had been put together with an effort, nevertheless attain a perfection of atmosphere which is astonishing. For the life of me I could not tell why this little restaurant seemed so bright, for there was nothing smart about it when you examined it in detail; and so I was compelled to attribute this impression to the probably all-pervading temperament of the owner. Always, in these cases, there is a man (or a woman) quite remarkable for his point of view. Otherwise you could not take such simple appointments and make them into anything so pleasing and so individual. A luncheon which had been ordered by telephone was now served; and at the beginning of its gastronomic wonders Mr. McG. and Miss N. arrived.

I shall not soon forget the interesting temperaments of these two; for even more than great institutions, persons who come reasonably close to you make up the atmosphere of a city. Mr. McG. was a solid, sandy, steady-eyed Scotchman who looked as though, had he not been an artist, he might have been a kilted soldier, swinging along with the enviable Scotch stride. Miss N. was a delightfully Parisianized American, without the slightest affectation, however, so far as I could make out, of either speech or manner. She was pleasingly good-looking, with black hair, a healthy, rounded face and figure, and a cheerful, good-natured air. There was no sense of either that aggressiveness or superiority which so often characterizes the female artist. We launched at once upon a discussion of Paris, London and New York and upon the delights of Paris and the progress of the neo-impressionist cult. I could see plainly that these two did not care to force their connection with that art development on my attention; but I was interested to know of it. There was something so solid and self-reliant about Mr. McG. that before the meal was over I had taken a fancy to him. He had the least suggestion of a Scotch burr in his voice which might have said “awaw” instead of away and “doon” instead of down; but it resulted in nothing so broad as that. They immediately gave me lists of restaurants that I must see in the Latin Quarter and asked me to come with them to the Café d’Harcourt and to Bullier’s to dance and to some of the brasseries to see what they were like. Between two and three Mr. McG. left because of an errand, and Barfleur and I accompanied Miss N. to her studio close by the gardens of the Luxembourg. This public garden which, not unlike the Tuileries on the other side of the Seine, was set with charming statues, embellished by a magnificent fountain, and alive with French nursemaids and their charges, idling Parisians in cutaways and derbies, and a smart world of pedestrians generally impressed me greatly. It was lovely. The wonder of Paris, as I was discovering, was that, walk where you would, it was hard to escape the sense of breadth, space, art, history, romance and a lovely sense of lightness and enthusiasm for life.

Miss N.’s studio is in the Rue Deñfert-Rochereau. In calling here I had my first taste of the Paris concierge, the janitress who has an eye on all those who come and go and to whom all not having keys must apply. In many cases, as I learned, keys are not given to the outer gate or door. One must ring and be admitted. This gives this person a complete espionage over the affairs of all the tenants, mail, groceries, guests, purchases, messages—anything and everything. If you have a charming concierge, it is well and good; if not, not. The thought of anything so offensive as a spying concierge irritated me greatly and I found myself running forward in my mind picking fights with some possible concierge who might at some remote date possibly trouble me. Of such is the contentious disposition.

The studio of Mr. McG., in the Boulevard Raspail, overlooks a lovely garden—a heavenly place set with trees and flowers and reminiscent of an older day in the bits of broken stone-work lying about, and suggesting the architecture of a bygone period. His windows, reaching from floor to ceiling and supplemented by exterior balconies, were overhung by trees. In both studios were scores of canvases done in the neo-impressionistic style which interested me profoundly.

It is one thing to see neo-impressionism hung upon the walls of a gallery in London, or disputed over in a West End residence. It is quite another to come upon it fresh from the easel in the studio of the artist, or still in process of production, defended by every thought and principle of which the artist is capable. In Miss N.’s studio were a series of decorative canvases intended for the walls of a great department store in America which were done in the raw reds, yellows, blues and greens of the neo-impressionist cult—flowers which stood out with the coarse distinctness of hollyhocks and sunflowers; architectural outlines which were as sharp as those of rough buildings, and men and women whose details of dress and feature were characterized by colors which by the uncultivated eye would be pronounced unnatural.

For me they had an immense appeal if for nothing more than that they represented a development and an individual point of view. It is so hard to break tradition.

It was the same in the studio of Mr. McG. to which we journeyed after some three-quarters of an hour. Of the two painters, the man seemed to me the more forceful. Miss N. worked in a softer mood, with more of what might be called an emotional attitude towards life.

During all this, Barfleur was in the heyday of his Parisian glory, and appropriately cheerful. We took a taxi through singing streets lighted by a springtime sun and came finally to the Restaurant Prunier where it was necessary for him to secure a table and order dinner in advance; and thence to the Théâtre des Capucines in the Rue des Capucines, where tickets for a farce had to be secured, and thence to a bar near the Avenue de l’Opéra where we were to meet the previously mentioned Mme. de B. who, out of the goodness of her heart, was to help entertain me while I was in the city.

This remarkable woman who by her beauty, simplicity, utter frankness, and moody immorality would shock the average woman into a deadly fear of life and make a horror of what seems a gaudy pleasure world to some, quite instantly took my fancy. Yet I think it was more a matter of Mme. de B.’s attitude, than it was the things which she did, which made it so terrible. But that is a long story.

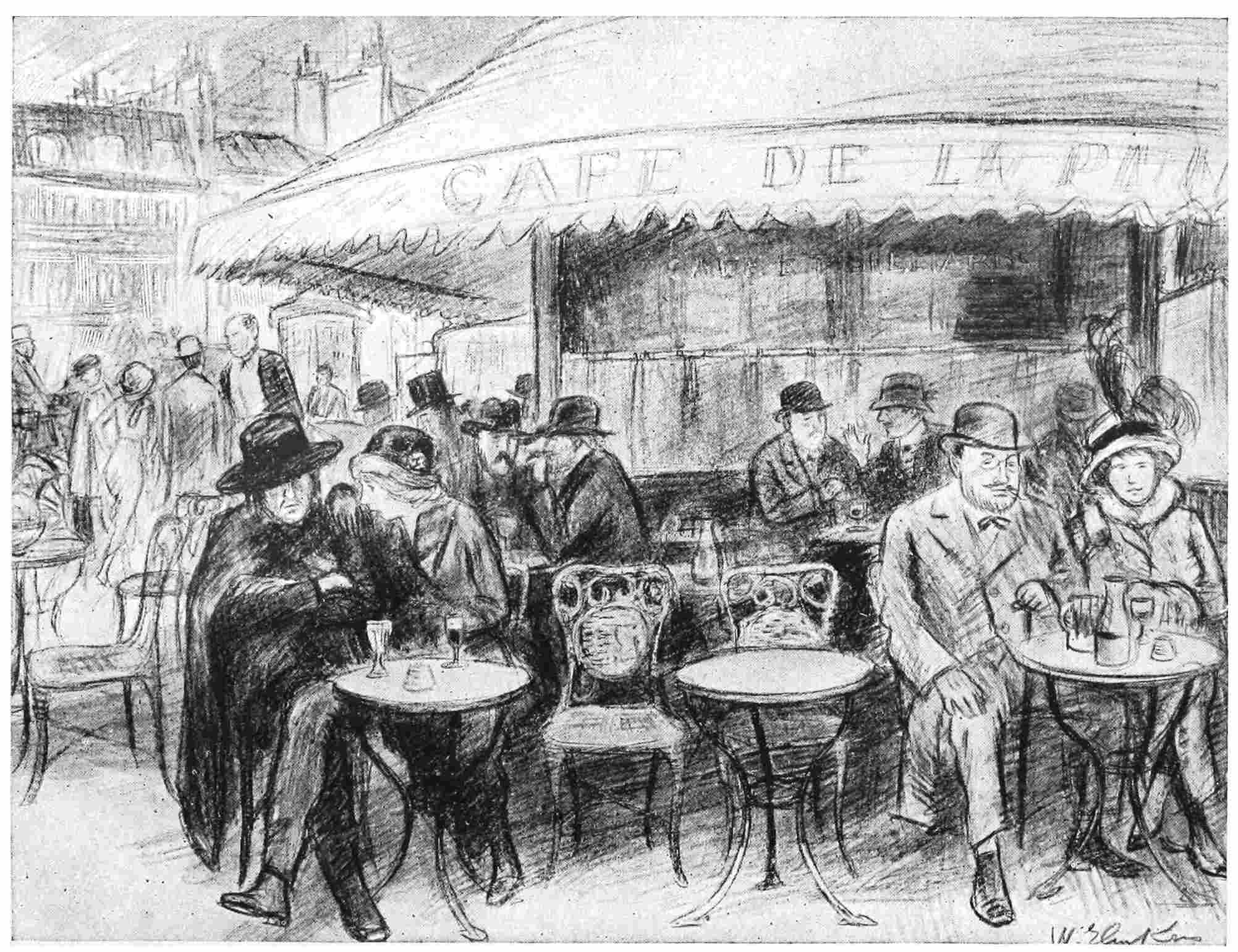

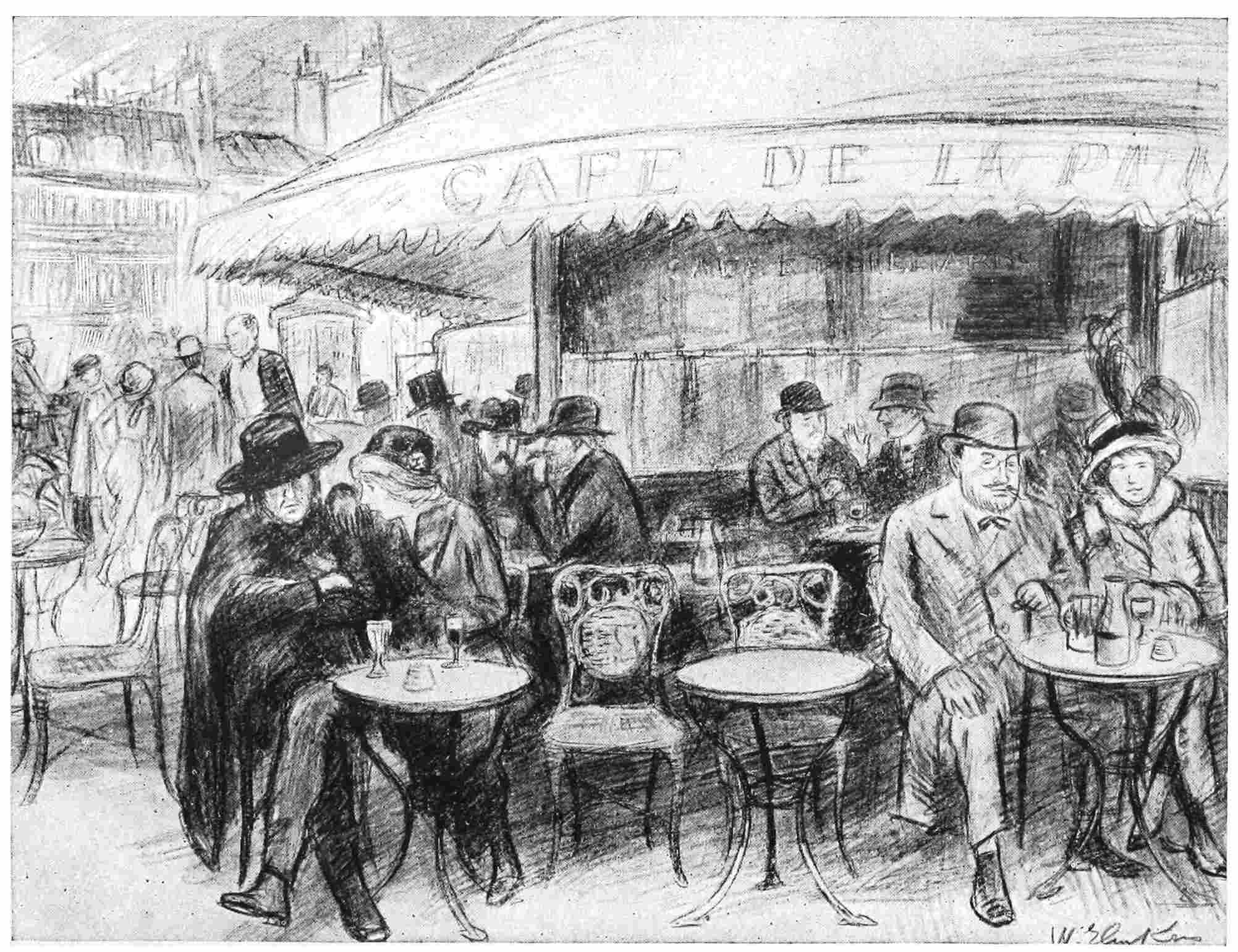

One of the thousands upon thousands of cafés on the boulevards of Paris

We came to her out of the whirl of the “green hour,” when the Paris boulevards in this vicinity were fairly swarming with people—the gayest world I have ever seen. We have enormous crowds in New York, but they seem to be going somewhere very much more definitely than in Paris. With us there is an eager, strident, almost objectionable effort to get home or to the theater or to the restaurant which one can easily resent—it is so inconsiderate and indifferent. In London you do not feel that there are any crowds that are going to the theaters or the restaurants; and if they are, they are not very cheerful about it; they are enduring life; they have none of the lightness of the Parisian world. I think it is all explained by the fact that Parisians feel keenly that they are living now and that they wish to enjoy themselves as they go. The American and the Englishman—the Englishman much more than the American—have decided that they are going to live in the future. Only the American is a little angry about his decision and the Englishman a little meek or patient. They both feel that life is intensely grim. But the Parisian, while he may feel or believe it, decides wilfully to cast it off. He lives by the way, out of books, restaurants, theaters, boulevards, and the spectacle of life generally. The Parisians move briskly, and they come out where they can see each other—out into the great wide-sidewalked boulevards and the thousands upon thousands of cafés; and make themselves comfortable and talkative and gay on the streets. It is so obvious that everybody is having a good time—not trying to have it; that they are enjoying the wine-like air, the cordials and apéritifs of the brasseries, the net-like movements of the cabs, the dancing lights of the roadways, and the flare of the shops. It may be chill or drizzling in Paris, but you scarcely feel it. Rain can scarcely drive the people off the streets. Literally it does not. There are crowds whether it rains or not, and they are not despondent. This particular hour that brought us to G.’s Bar was essentially thrilling, and I was interested to see what Mme. de B. was like.