CHAPTER XXIII

THREE GUIDES

IT was only by intuition, and by asking many questions, that at times I could extract the significance of certain places from Barfleur as quickly as I wished. He was always reticent or a little cryptic in his allusions. In this instance I gathered rapidly however that this bar was a very extraordinary little restaurant presided over by a woman of a most pleasant and practical type. She could not have been much over forty—buxom, good-looking, self-reliant, efficient. She moved about the two rooms which constituted her restaurant, in so far as the average diner was concerned, with an air of considerable social importance. Her dresses, as I noticed on my several subsequent visits, were always sober, but in excellent taste. About this time of day the two rooms were a little dark, the electric lights being reserved for the more crowded hours. Yet there were always a few people here. This evening when we entered I noticed a half-dozen men and three or four young women lounging here in a preliminary way, consuming apéritifs and chatting sociably. I made out by degrees that the mistress of this place had a following of a kind, in the Parisian scheme of things—that certain men and women came here for reasons of good-fellowship; and that she would take a certain type of struggling maiden, if she were good-looking and ambitious and smart, under her wing. The girl would have to know how to dress well, to be able to carry herself with an air; and when money was being spent very freely by an admirer it might as well be spent at this bar on occasion as anywhere else. There was obviously an entente cordiale between Madame G. and all the young women who came in here. They seemed so much at home that it was quite like a family party. Everybody appeared to be genial, cheerful, and to know everybody else. To enter here was to feel as though you had lived in Paris for years.

While we are sitting at a table sipping a brandy and soda, enter Mme. de B., the brisk, genial, sympathetic French personage whose voice on the instant gave me a delightful impression of her. It was the loveliest voice I have ever heard, soft and musical, a colorful voice touched with both gaiety and sadness. Her eyes were light blue, her hair brown and her manner sinuous and insinuating. She seemed to have the spirit of a delightfully friendly collie dog or child and all the gaiety and alertness that goes with either.

After I had been introduced, she laughed, and putting aside her muff and stole, shook herself into a comfortable position in a corner and accepted a brandy and soda. She was so interested for the moment, exchanging whys and wherefores with Barfleur, that I had a chance to observe her keenly. In a moment she turned to me and wanted to know whether I knew either of two American authors whom she knew—men of considerable repute. Knowing them both very well, it surprised me to think that she knew them. She seemed, from the way she spoke, to have been on the friendliest terms with both of them; and any one by looking at her could have understood why they should have taken such an interest in her.

“Now, you know, that Mistaire N., he is very nice. I was very fond of him. And Mistaire R., he is clever, don’t you think?”

I admitted at once that they were both very able men and that I was glad that she knew them. She informed me that she had known Mr. R. and Mr. N. in London and that she had there perfected her English, which was very good indeed. Barfleur explained in full who I was and how long I would be in Paris and that he had written her from America because he wanted her to show me some attention during my stay in Paris.

If Mme. de B. had been of a somewhat more calculating type I fancy that, with her intense charm of face and manner and her intellect and voice, she would have been very successful. I gained the impression that she had been on the stage in some small capacity; but she had been too diffident—not really brazen enough—for the grim world in which the French actress rises. I soon found that Mme. de B. was a charming blend of emotion, desire, and refinement which had strayed into the wrong field. She would have done better in literature or music or art; and she seemed fitted by her moods and her understanding to be a light in any one of them or all. Some temperaments are so—missing by a fraction what they would give all the world to have. It is the little things that do it—the fractions, the bits, the capacity for taking pains in little things that make, as so many have said, the difference between success and failure and it is true.

I shall never forget how she looked at me, quite in the spirit of a gay uncertain child, and how quickly she made me feel that we would get along very well together. “Why, yes,” she said quite easily in her soft voice, “I will go about with you, although I would not know what is best to see. But I shall be here, and if you want to come for me we can see things together.” Suddenly she reached over and took my hand and squeezed it genially, as though to seal the bargain. We had more drinks to celebrate this rather festive occasion; and then Mme. de B., promising to join us at the theater, went away. It was high time then to dress for dinner; and so we returned to the hotel. We ate a companionable meal, watching the Parisian and his lady love (or his wife) arrive in droves and dine with that gusto and enthusiasm which is so characteristic of the French.

When we came out of this theater at half after eleven, Mme. de B. was anxious to return to her apartment, and Barfleur was anxious to give me an extra taste of the varied café life of Paris in order that I might be able to contrast and compare intelligently. “If you know where they are and see whether you like them, you can tell whether you want to see any more of them—which I hope you won’t,” said he wisely, leading the way through a swirling crowd that was for all the world like a rushing tide of the sea.

There are no traffic laws in Paris, so far as I could make out; vehicles certainly have the right-of-way and they go like mad. I have read of the Parisian authorities having imported a London policeman to teach Paris police the art of traffic regulation, but if so, the instruction has been wasted. This night was a bedlam of vehicles and people. A Paris guide, one of the tribe that conducts the morbid stranger through scenes that are supposedly evil, and that I know from observation to be utterly vain, approached us in the Boulevard des Capucines with the suggestion that he be allowed to conduct us through a realm of filthy sights, some of which he catalogued. I could give a list of them if I thought any human organization would ever print them, or that any individual would ever care to read them—which I don’t. I have indicated before that Barfleur is essentially clean-minded. He is really interested in the art of the demi-mondaine, and the spectacle which their showy and, to a certain extent, artistic lives present; but no one in this world ever saw more clearly through the shallow make-believe of this realm than he does. He contents himself with admiring the art and the tragedy and the pathos of it. This world of women interests him as a phase of the struggle for existence, and for the artistic pretense which it sometimes compels. To him the vast majority of these women in Paris were artistic—whatever one might say for their morals, their honesty, their brutality and the other qualities which they possess or lack; and whatever they were, life made them so—conditions over which their temperaments, understandings and wills had little or no control. He is an amazingly tolerant man—one of the most tolerant I have ever known, and kindly in his manner and intention.

Nevertheless, he has an innate horror of the purely physical when it descends to inartistic brutality. There is much of that in Paris; and these guides advertise it; but it is filth especially arranged for the stranger. I fancy the average Parisian knows nothing about it; and if he does, he has a profound contempt for it. So has the well-intentioned stranger, but there is always an audience for this sort of thing. So when this guide approached us with the proposition to show us a selected line of vice, Barfleur took him genially in hand. “Stop a moment, now,” he said, with his high hat on the back of his head, his fur coat expansively open, and his monocled eye fixing the intruder with an inquiring gaze, “tell me one thing—have you a mother?”

The small Jew who was the industrious salesman for this particular type of ware looked his astonishment.

They are used to all sorts of set-backs—these particular guides—for they encounter all sorts of people, severely moral and the reverse; and I fancy on occasion they would be soundly trounced if it were not for the police who stand in with them and receive a modicum for their protection. They certainly learn to understand something of the type of man who will listen to their proposition; for I have never seen them more than ignored and I have frequently seen them talked to in an off-hand way, though I was pleased to note that their customers were few.

This particular little Jew had a quizzical, screwed-up expression on his face, and did not care to answer the question at first; but resumed his announcement of his various delights and the price it would all cost.

“Wait, wait, wait,” insisted Barfleur, “answer my question. Have you a mother?”

“What has that got to do with it?” asked the guide. “Of course I have a mother.”

“Where is she?” demanded Barfleur authoritatively.

“She’s at home,” replied the guide, with an air of mingled astonishment, irritation and a desire not to lose a customer.

“Does she know that you are out here on the streets of Paris doing what you are doing to-night?” he continued with a very noble air.

The man swore under his breath.

“Answer me,” persisted Barfleur, still fixing him solemnly through his monocle. “Does she?”

“Why, no, of course she doesn’t,” replied the Jew sheepishly.

“Would you want her to know?” This in sepulchral tones.

“No, I don’t think so.”

“Have you a sister?”

“Yes.”

“Would you want her to know?”

“I don’t know,” replied the guide defiantly. “She might know anyhow.”

“Tell me truly, if she did not know, would you want her to know?”

The poor vender looked as if he had got into some silly, inexplicable mess from which he would be glad to free himself; but he did not seem to have sense enough to walk briskly away and leave us. Perhaps he did not care to admit defeat so easily.

“No, I suppose not,” replied the interrogated vainly.

“There you have it,” exclaimed Barfleur triumphantly. “You have a mother—you would not want her to know. You have a sister—you would not want her to know. And yet you solicit me here on the street to see things which I do not want to see or know. Think of your poor gray-headed mother,” he exclaimed grandiloquently, and with a mock air of shame and sorrow. “Once, no doubt, you prayed at her knee, an innocent boy yourself.”

The man looked at him in dull suspicion.

“No doubt if she saw you here to-night, selling your manhood for a small sum of money, pandering to the lowest and most vicious elements in life, she would weep bitter tears. And your sister—don’t you think now you had better give up this evil life? Don’t you think you had better accept any sort of position and earn an honest living rather than do what you are doing?”

“Well, I don’t know,” said the man. “This living is as good as any other living. I’ve worked hard to get my knowledge.”

“Good God, do you call this knowledge?” inquired Barfleur solemnly.

“Yes, I do,” replied the man. “I’ve worked hard to get it.”

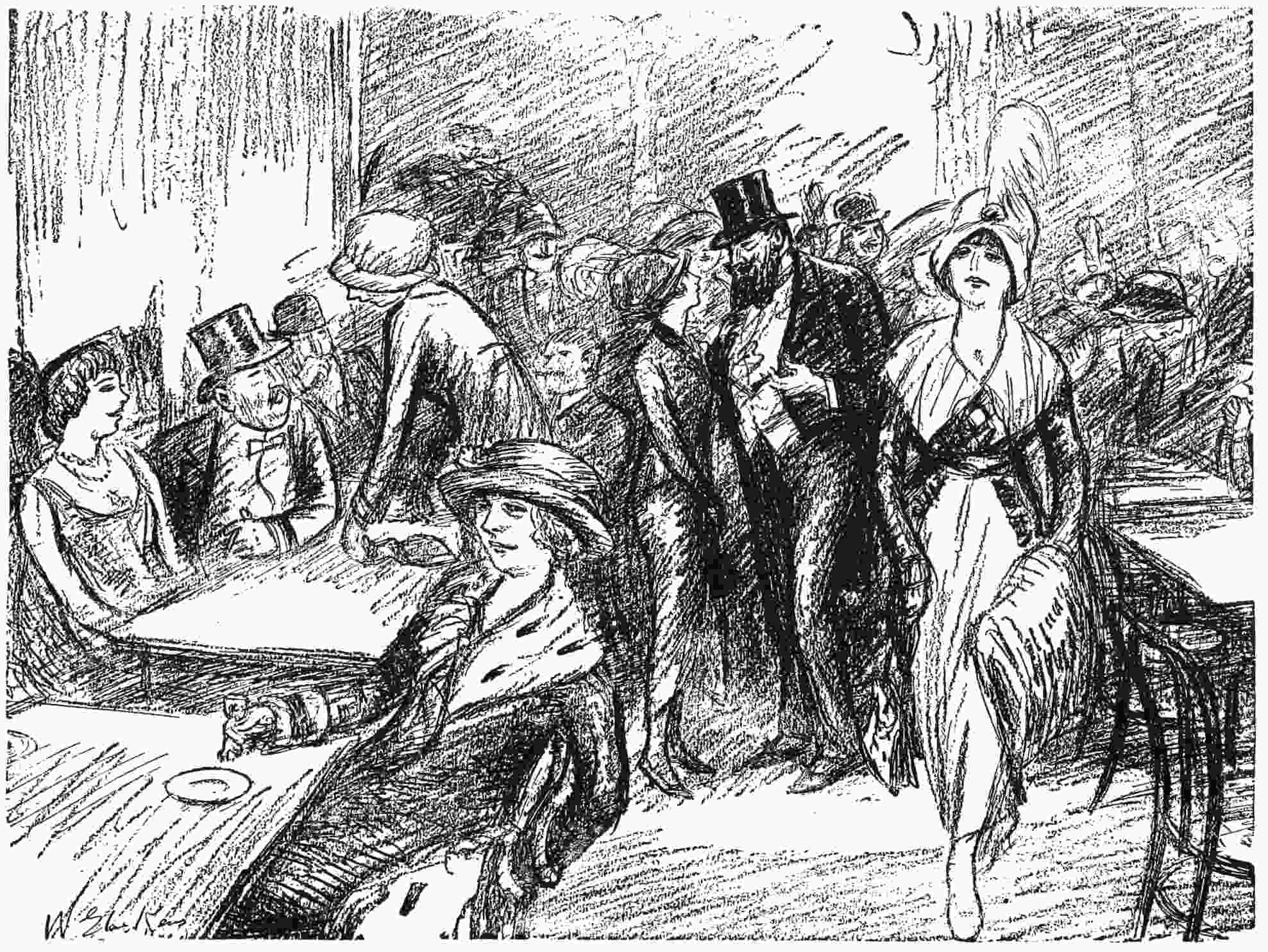

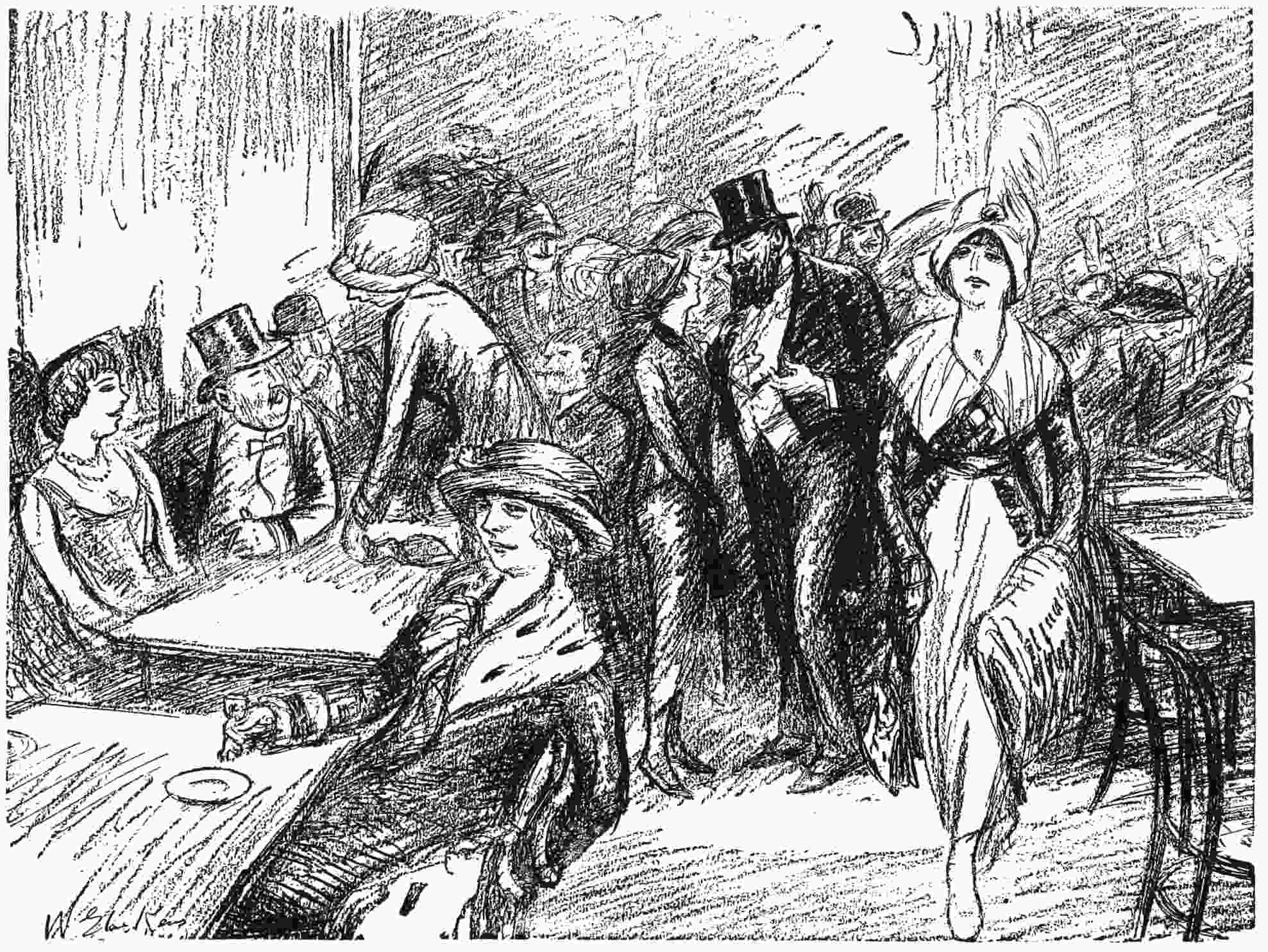

These places were crowded with a gay and festive throng

“My poor friend,” replied Barfleur, “I pity you. From the bottom of my heart I pity you. You are degrading your life and ruining your soul. Come now, to-morrow is Sunday. The church bells will be ringing. Go to church. Reform your life. Make a new start—do. You will never regret it. Your old mother will be so glad—and your sister.”

“Oh, say,” said the man, walking off, “you don’t want a guide. You want a church.” And he did not even look back.

“It is the only way I have of getting rid of them,” commented Barfleur. “They always stop when I begin to talk to them about their mother. They can’t stand the thought of their mother.”

“Very true,” I said. “Cut it out now, and come on. You have preached enough. Let us see the worst that Paris has to show.” And off we went, arm in arm.

Thereafter we visited restaurant after restaurant,—high, low, smart, dull,-and I can say truly that the strange impression which this world made on me lingers even now. Obviously, when we arrived at Fysher’s at twelve o’clock, the fun was just getting under way. Some of these places, like this Bar Fysher, were no larger than a fair-sized room in an apartment, but crowded with a gay and festive throng—Americans, South Americans, English and others. One of the tricks in Paris to make a restaurant successful is to keep it small so that it has an air of overflow and activity. Here at Fysher’s Bar, after allowing room for the red-jacketed orchestra, the piano and the waiters, there was scarcely space for the forty or fifty guests who were present. Champagne was twenty francs the bottle and champagne was all they served. It was necessary here, as at all the restaurants, to contribute to the support of the musicians; and if a strange young woman should sit at your table for a moment and share either the wine or the fruit which would be quickly offered, you would have to pay for that. Peaches were three francs each, and grapes five francs the bunch. It was plain that all these things were offered in order that the house might thrive and prosper. It was so at each and all of them.