CHAPTER XLVII

BERLIN

BERLIN, when I reached it, first manifested itself in a driving rain. If I laugh at it forever and ever as a blunder-headed, vainglorious, self-appreciative city I shall always love it too. Paris has had its day, and will no doubt have others; London is content with an endless, conservative day; Berlin’s is still to come and come brilliantly. The blood is there, and the hope, and the moody, lustful, Wagnerian temperament.

But first, before I reached it, I suffered a strange mental revolt at being in Germany at all. Why? I can scarcely say. Perhaps I was beginning to be depressed with what in my prejudice I called the dullness of Germany. A little while later I recognized that while there is an extreme conflict of temperament between the average German and myself, I could yet admire them without wishing to be anything like them. Of all the peoples I saw I should place the Germans first for sobriety, industry, thoroughness, a hearty intolerance of sham, a desire and a willingness to make the best of a very difficult earthly condition. In many respects they are not artistically appetizing, being gross physically, heartily passionate, vain, and cocksure; but those things after all are unimportant. They have, in spite of all their defects, great emotional, intellectual, and physical capacities, and these things are important. I think it is unquestionable that in the main they take life far too seriously. The belief in a hell, for instance, took a tremendous grip on the Teutonic mind and the Lutheran interpretation of Protestantism, as it finally worked out, was as dreary as anything could be—almost as dreary as Presbyterianism in Scotland. That is the sad German temperament. A great nationality, business success, public distinction is probably tending to make over or at least modify the Teutonic cast of thought which is gray; but in parts of Germany, for instance at Mayence, you see the older spirit almost in full force.

In the next place I was out of Italy and that land had taken such a strange hold on me. What a far cry from Italy to Germany! I thought. Gone; once and for all, the wonderful clarity of atmosphere that pervades almost the whole of Italy from the Alps to Rome and I presume Sicily. Gone the obvious dolce far niente, the lovely cities set on hills, the castles, the fortresses, the strange stone bridges, the hot, white roads winding like snowy ribbons in the distance. No olive trees, no cypresses, no umbrella trees or ilexes, no white, yellow, blue, brown and sea-green houses, no wooden plows, white oxen and ambling, bare-footed friars. In its place (the Alps and Switzerland between) this low rich land, its railroads threading it like steel bands, its citizens standing up as though at command, its houses in the smaller towns almost uniformly red, its architecture a twentieth century modification of an older order of many-gabled roofs—the order of Albrecht Dürer—with its fanciful decorations, conical roofs and pinnacles and quaint windows and doors that suggest the bird-boxes of our childhood. Germany appears in a way to have attempted to abandon the medieval architectural ideal that still may be seen in Mayence, Mayen, the heart of Frankfort, Nuremberg, Heidelberg and other places and to adapt its mood to the modern theory of how buildings ought to be constructed, but it has not quite done so. The German scroll-loving mind of the Middle Ages is still the German scroll-loving mind of to-day. Look and you will see it quaintly cropping out everywhere. Not in those wonderful details of intricacy, Teutonic fussiness, naïve, jester-like grotesqueness which makes the older sections of so many old German cities so wonderful, but in a slight suggestion of them here and there—a quirk of roof, an over-elaborateness of decoration, a too protuberant frieze or grape-viney, Bacchus-mooded, sex-ornamented panel, until you say to yourself quite wisely, “Ah, Teutons will be Teutons still.” They are making a very different Germany from what the old Germany was—modern Germany dating from 1871—but it is not an entirely different Germany. Its citizens are still stocky, red-blooded, physically excited and excitable, emotional, mercurial, morbid, enthusiastic, women-loving and life-loving, and no doubt will be so, praise God, until German soil loses its inherent essentials, and German climate makes for some other variations not yet indicated in the race.

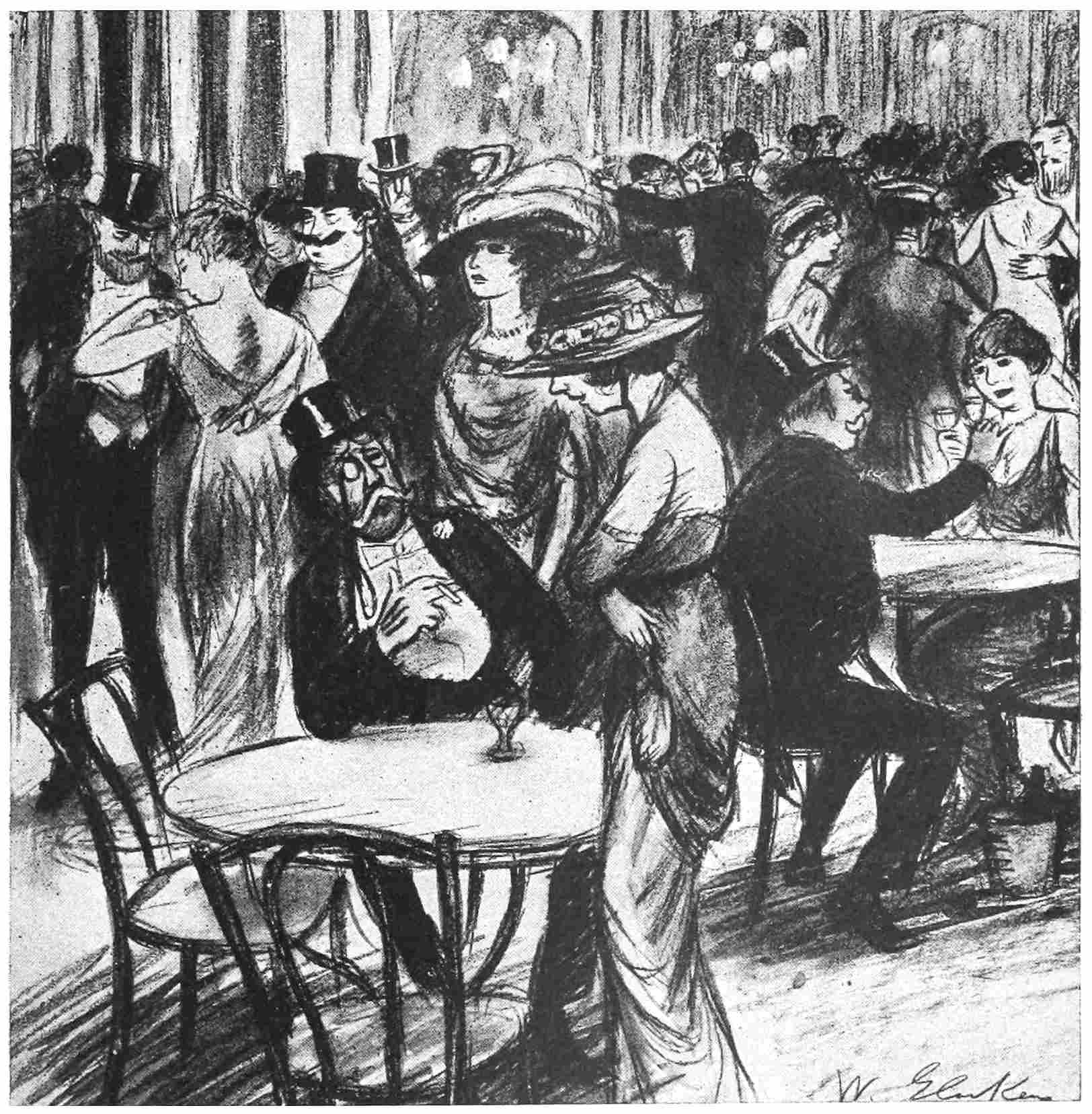

A German dance hall, Berlin

But to return to Berlin. I saw it first jogging down Unter den Linden from the Friedrichstrasse Bahnhof (station) to Cook’s Berlin agency, seated comfortably in a closed cab behind as fat a horse and driver as one would wish to see. And from there, still farther along Unter den Linden and through the Wilhelmstrasse to Leipzigstrasse and the Potsdamer Bahnhof I saw more of it. Oh, the rich guttural value of the German “platzes” and “strasses” and “ufers” and “dams.” They make up a considerable portion of your city atmosphere for you in Berlin. You just have to get used to them—just as you have to accept the “fabriks” and the “restaurations” and the “wein handlungs,” and all the other “ichs,” “lings,” “bergs,” “brückes,” until you sigh for the French and Italian “-rics” and the English-American “-rys.” However, among the first things that impressed me were these: all Berlin streets, seemingly, were wide with buildings rarely more than five stories high. Everything, literally everything, was American new—and newer—German new! And the cabbies were the largest, fattest, most broad-backed, most thick-through and Deutschiest looking creatures I have ever beheld. Oh, the marvel of those glazed German cabby hats with the little hard rubber decorations on the side. Nowhere else in Europe is there anything like these cabbies. They do not stand; they sit, heavily and spaciously—alone.

The faithful Baedeker has little to say for Berlin. Art? It is almost all in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, in the vicinity of the Kupferdam. And as for public institutions, spots of great historic interest—they are a dreary and negligible list. But, nevertheless and notwithstanding, Berlin appealed to me instantly as one of the most interesting and forceful of all the cities, and that solely because it is new, crude, human, growing feverishly, unbelievably; and growing in a distinct and individual way. They have achieved and are achieving something totally distinct and worth while—a new place to go; and after a while, I haven’t the slightest doubt, thousands and even hundreds of thousands of travelers will go there. But for many and many a day the sensitive and artistically inclined will not admire it.

My visit to Cook’s brought me a mass of delayed mail which cheered me greatly. It was now raining pitchforks but my bovine driver, who looked somehow like a segment of a wall, managed to bestow my trunk and bags in such a fashion that they were kept dry, and off we went for the hotel. I had a preconceived notion that Unter den Linden was a magnificent avenue lined shadily with trees and crowded with palaces. Nothing could have been more erroneous. The trees are few and insignificant, the palaces entirely wanting. It is a very wide business street, lined with hotels, shops, restaurants, newspaper offices and filled with a parading throng in pleasant weather. At one end it gives into an area known as the Lustgarten crowded with palaces, art galleries, the Berlin Cathedral, the Imperial Opera House and what not; at the other end (it is only about a mile long) into the famous Berlin Thiergarten, formerly a part of the Imperial (Hohenzollern) hunting-forest. On the whole, the avenue was a disappointment.

For suggestions of character, individuality, innate Teutonic charm or the reverse—as these things strike one—growth, prosperity, promise, and the like, Berlin cannot be equaled in Europe. Quite readily I can see how it might irritate and repel the less aggressive denizens of less hopeful and determined realms. The German, when he is oppressed is terribly depressed; when he is in the saddle, nothing can equal his bump of I-am-ity. It becomes so balloon-like and astounding that the world may only gaze in astonishment or retreat in anger, dismay, or uproarious amusement. The present-day Germans do take themselves so seriously and from many points of view with good reason, too.

I don’t know where in Europe, outside of Paris, if even there, you will see a better-kept city. It is so clean and spruce and fresh that it is a joy to walk there—anywhere. Mile after mile of straight, imposing streets greet your gaze. Berlin needs a great Pantheon, an avenue such as Unter den Linden lined with official palaces (not shops), and unquestionably a magnificent museum of art—I mean a better building. Its present public and imperial structures are most uninspired. They suggest the American-European architecture of 1860–1870. The public monuments of Berlin, and particularly their sculptural adornments are for the most part a crime against humanity.

I remember standing and looking one evening at that noble German effort known as the memorial statue of William I, in the Lustgarten, unquestionably the fiercest and most imposing of all the Berlin military sculptures. This statue speaks loudly for all Berlin and for all Germany and for just what the Teutonic disposition would like to be—namely, terrible, colossal, astounding, world-scarifying, and the like. It almost shouts “Ho! see what I am,” but the sad part of it is that it does it badly, not with that reserve that somehow invariably indicates tremendous power so much better than mere bluster does. What the Germans seem not to have learned in their art at least is that “easy does it.” Their art is anything but easy. It is almost invariably showy, truculent, vainglorious. But to continue: The whole neighborhood in which this statue occurs, and the other neighborhood at the other end of Unter den Linden, where stands the Reichstag and the like, all in the center of Berlin, as it were, is conceived, designed, and executed (in my judgment) in the same mistaken spirit. Truly, when you look about you at the cathedral (save the mark) or the Royal Palace in the Lustgarten, or at the Winged Victory before the Reichstag or at the Reichstag itself, and the statue of Bismarck in the Königs-Platz (the two great imperial centers), you sigh for the artistic spirit of Italy. But no words can do justice to the folly of spending three million dollars to erect such a thing as this Berlin Dom or cathedral. It is so bad that it hurts. And I am told that the Kaiser himself sanctioned some of the architectural designs. And it was only completed between 1894 and 1906. Shades of Brabante and Pisano!

But if I seem disgusted with this section of Berlin—its evidence of Empire, as it were—there was much more that truly charmed me. Wherever I wandered I could perceive through all the pulsing life of this busy city the thoroughgoing German temperament—its moody poverty, its phlegmatic middle-class prosperity, its aggressive commercial, financial, and, above all, its official and imperial life. Berlin is shot through with the constant suggestion of officialism and imperialism. The German policeman with his shining brass helmet and brass belt; the Berlin sentry in his long military gray overcoat, his musket over his shoulder, his high cap shading his eyes, his black-and-white striped sentry-box behind him, stationed apparently at every really important corner and before every official palace; the German military and imperial automobiles speeding their independent ways, all traffic cleared away before them, the small flag of officialdom or imperialism fluttering defiantly from the foot-rails as they flash at express speed past you;—these things suggest an individuality which no other European city that I saw quite equaled. It represented what I would call determination, self-sufficiency, pride. Berlin is new, green, vigorous, astounding—a city that for speed of growth puts Chicago entirely into the shade; that for appearance, cleanliness, order, for military precision and thoroughness has no counterpart anywhere. It suggests to you all the time, something very much greater to come which is the most interesting thing that can be said about any city, anywhere.

One panegyric I should like to write on Berlin concerns not so much its social organization as a city, though that is interesting enough, but specifically its traffic and travel arrangements. To be sure it is not yet such a city as either New York, London or Paris, but it has over three million people, a crowded business heart and a heavy, daily, to-and-fro-swinging tide of suburban traffic. There are a number of railway stations in the great German capital, the Potsdamer Bahnhof, the Friedrichstrasse Bahnhof, the Anhalter Bahnhof and so on, and coming from each in the early hours of the morning, or pouring toward them at evening are the same eager streams of people that one meets in New York at similar hours.

The Germans are amazingly like the Americans. Sometimes I think that we get the better portion of our progressive, constructive characteristics from them. Only, the Germans, I am convinced, are so much more thorough. They go us one better in economy, energy, endurance, and thoroughness. The American already is beginning to want to play too much. The Germans have not reached that stage.

The railway stations I found were excellent, with great switching-yards and enormous sheds arched with glass and steel, where the trains waited. In Berlin I admired the suburban train service as much as I did that of London, if not more. That in Paris was atrocious. Here the trains offered a choice of first, second, and third class, with the vast majority using the second and third. I saw little difference in the crowds occupying either class. The second-class compartments were upholstered in a greyish-brown corduroy. The third-class seats were of plain wood, varnished and scrupulously clean. I tried all three classes and finally fixed on the third as good enough for me.

I wish all Americans who at present suffer the indignities of the American street-railway and steam-railway suburban service could go to Berlin and see what that city has to teach them in this respect. Berlin is much larger than Chicago. It is certain soon to be a city of five or six millions of people—very soon. The plans for handling this mass of people comfortably and courteously are already in operation. The German public service is obviously not left to supposedly kindly minded business gentlemen—“Christian gentlemen,”—as Mr. Baer of the Reading once chose to put it, “in partnership with God.” The populace may be underlings to an imperial Kaiser, subject to conscription and eternal inspection, but at least the money-making “Christian gentlemen” with their hearts and souls centered on their private purses and working, as Mr. Croker once said of himself, “for their own pockets all the time,” are not allowed to “take it out of” the rank and file.

No doubt the German street-railways and steam-railways are making a reasonable sum of money and are eager to make more. I haven’t the least doubt but that heavy, self-opinionated, vainglorious German directors of great wealth gather around mahogany tables in chambers devoted to meetings of directors and listen to ways and means of cutting down expenses and “improving” the service. Beyond the shadow of a doubt there are hard, hired managers, eager to win the confidence and support of their superiors and ready to feather their own nests at the expense of the masses, who would gladly cut down the service, “pack ’em in,” introduce the “cutting out” system of car service and see that the “car ahead” idea was worked to the last maddening extreme; but in Germany, for some strange, amazing reason, they don’t get a chance. What is the matter with Germany, anyhow? I should like to know. Really I would. Why isn’t the “Christian gentleman” theory of business introduced there? The population of Germany, acre for acre and mile for mile, is much larger than that of America. They have sixty-five million people crowded into an area as big as Texas. Why don’t they “pack ’em in”? Why don’t they introduce the American “sardine” subway service? You don’t find it anywhere in Germany, for some strange reason. Why? They have a subway service in Berlin. It serves vast masses of people, just as the subway does in New York; its platforms are crowded with people. But you can get a seat just the same. There is no vociferated “step lively” there. Overcrowding isn’t a joke over there as it is here—something to be endured with a feeble smile until you are spiritually comparable to a door mat. There must be “Christian gentlemen” of wealth and refinement in Germany and Berlin. Why don’t they “get on the job”? The thought arouses strange uncertain feelings in me.

Take, for instance, the simple matter of starting and stopping street-railway cars in the Berlin business heart. In so far as I could see, that area, mornings and evenings, was as crowded as any similar area in Paris, London, or New York. Street-cars have to be run through it, started, stopped; passengers let on and off—a vast tide carried in and out of the city. Now the way this matter is worked in New York is quite ingenious. We operate what might be described as a daily guessing contest intended to develop the wits, muscles, lungs, and tempers of the people. The scheme, in so far as the street railway companies are concerned, is (after running the roads as economically as possible) to see how thoroughly the people can be fooled in their efforts to discover when and where a car will stop. In Berlin, however, they have, for some reason, an entirely different idea. There the idea is not to fool the people at all but to get them in and out of the city as quickly as possible. So, as in Paris, London, Rome, and elsewhere, a plan of fixed stopping-places has been arranged. Signs actually indicate where the cars stop and there—marvel of marvels—they all stop even in the so-called rush hours. No traffic policeman, apparently, can order them to go ahead without stopping. They must stop. And so the people do not run for the cars, the motorman has no joy in outwitting anybody. Perhaps that is why the Germans are neither so agile, quick-witted, or subtle as the Americans.

And then, take in addition—if you will bear with me another moment—this matter of the Berlin suburban service as illustrated by the lines to Potsdam and elsewhere. It is true the officers, and even the Emperor of Germany, living at Potsdam and serving the Imperial German Government there may occasionally use this line, but thousands upon thousands of intermediate and plebeian Germans use it also. You can always get a seat. Please notice this word always. There are three classes and you can always get a seat in any class—not the first or second classes only, but the third class and particularly the third class. There are “rush” hours in Berlin just as there are in New York, dear reader. People swarm into the Berlin railway stations and at Berlin street-railway corners and crowd on cars just as they do here. The lines fairly seethe with cars. On the tracks ranged in the Potsdamer Bahnhof, for instance, during the rush hours, you will see trains consisting of eleven, twelve, and thirteen cars, mostly third-class accommodation, waiting to receive you. And when one is gone, another and an equally large train is there on the adjoining track and it is going to leave in another minute or two also. And when that is gone there will be another, and so it goes.

There is not the slightest desire evident anywhere to “pack” anybody in. There isn’t any evidence that anybody wants to make anything (dividends, for instance) out of straps. There are no straps. These poor, unliberated, Kaiser-ruled people would really object to straps and standing in the aisles, They would compel a decent service and there would be no loud cries on the part of “Christian gentlemen” operating large and profitable systems as to the “rights of property,” the need of “conserving the constitution,” the privilege of appealing to Federal judges, and the right of having every legal technicality invoked to the letter;—or, if there were, they would get scant attention. Germany just doesn’t see public service in that light. It hasn’t fought, bled, and died, perhaps, for “liberty.” It hasn’t had George Washington and Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. All it has had is Frederick the Great and Emperor William I and Bismarck and Von Moltke. Strange, isn’t it? Queer, how Imperialism apparently teaches people to be civil, while Democracy does the reverse. We ought to get a little “Imperialism” into our government, I should say. We ought to make American law and American government supreme, but over it there ought to be a “supremer” people who really know what their rights are, who respect liberties, decencies, and courtesies for themselves and others, and who demand and see that their government and their law and their servants, public and private, are responsive and responsible to them, rather than to the “Christian gentlemen” who want to “pack ’em in.” If you don’t believe it, go to Berlin and then see if you come home again cheerfully believing that this is still the land of the free and the home of the brave. Rather I think you will begin to feel that we are getting to be the land of the dub and the home of the door-mat. Nothing more and nothing less.