CHAPTER XLVIII

THE NIGHT-LIFE OF BERLIN

DURING the first ten days I saw considerable of German night-life, in company with Herr A., a stalwart Prussian who went out of his way to be nice to me. I cannot say that, after Paris and Monte Carlo, I was greatly impressed, although all that I saw in Berlin had this advantage, that it bore sharply the imprint of German nationality. The cafés were not especially noteworthy. I do not know what I can say about any of them which will indicate their individuality. “Piccadilly” was a great evening drinking-place near the Potsdamer Platz, which was all glass, gold, marble, glittering with lights and packed with the Germans, en famille, and young men and their girls.

“La Clou” was radically different. In a way it was an amazing place, catering to the moderately prosperous middle class. It seated, I should say, easily fifteen hundred people, if not more, on the ground floor; and every table, in the evening at least, was full. At either end of the great center aisle bisecting it was stationed a stringed orchestra and when one ceased the other immediately began, so that there was music without interruption. Father and mother and young Lena, the little Heine, and the two oldest girls or boys were all here. During the evening, up one aisle and down another, there walked a constant procession of boys and girls and young men and young women, making shy, conservative eyes at one another.

In Berlin every one drinks beer or the lighter wines—the children being present—and no harm seems to come from it. I presume drunkenness is not on the increase in Germany. And in Paris they sit at tables in front of cafés—men and women—and sip their liqueurs. It is a very pleasant way to enjoy your leisure. Outside of trade or the desire to be president, vice-president, or secretary of something, we in America have so often no real diversions.

In no sense could either of these restaurants be said to be smart. But Berlin, outside of one or two selected spots, does not run to smartness. The “Cabaret Linden” and the “Cabaret Arcadia” were, once more, of a different character. There was one woman at the Cabaret Linden who struck me as having real artistic talent of a strongly Teutonic variety. Claire Waldoff was her name, a hard, shock-headed tomboy of a girl, who sang in a harsh, guttural voice of soldiers, merchants, janitors, and policemen—a really brilliant presentation of local German characteristics. It is curious how these little touches of character drawn from everyday life invariably win thunders of applause. How the world loves the homely, the simple, the odd, the silly, the essentially true! Unlike the others at this place, there was not a suggestive thing about anything which this woman said or did; yet this noisy, driveling audience could not get enough of her. She was truly an artist.

One night we went to the Palais de Danse, admittedly Berlin’s greatest night-life achievement. For several days Herr A. had been saying: “Now to-morrow we must go to the Palais de Danse, then you will see something,” but every evening when we started out, something else had intervened. I was a little skeptical of his enthusiastic praise of this institution as being better than anything else of its kind in Europe. You had to take Herr A.’s vigorous Teutonic estimate of Berlin with a grain of salt, though I did think that a city that had put itself together in this wonderful way in not much more than a half-century had certainly considerable reason to boast.

“But what about the Café de Paris at Monte Carlo?” I suggested, remembering vividly the beauty and glitter of the place.

“No, no, no!” he exclaimed, with great emphasis—he had a habit of unconsciously making a fist when he was emphatic—“not in Monte Carlo, not in Paris, not anywhere.”

“Very good,” I replied, “this must be very fine. Lead on.”

So we went.

I think Herr A. was pleased to note how much of my skepticism melted after passing the sedate exterior of this astounding place.

“I want to tell you something,” said Herr A. as we climbed out of our taxi—a good, solid, reasonably priced, Berlin taxi—“if you come with your wife, your daughter, or your sister you buy a ticket for yourself—four marks—and walk in. Nothing is charged for your female companions and no notice is taken of them. If you come here with a demi-mondaine, you pay four marks for yourself and four for her, and you cannot get in without. They know. They have men at the door who are experts in this matter. They want you to bring such women, but you have to pay. If such a woman comes alone, she goes in free. How’s that?”

Once inside we surveyed a brilliant spectacle—far more ornate than the Café l’Abbaye or the Café Maxim, though by no means so enticing. Paris is Paris and Berlin is Berlin and the Germans cannot do as do the French. They haven’t the air—the temperament. Everywhere in Germany you feel that—that strange solidity of soul which cannot be gay as the French are gay. Nevertheless the scene inside was brilliant. Brilliant was the word. I would not have believed, until I saw it, that the German temperament or the German sense of thrift would have permitted it and yet after seeing the marvelous German officer, why not?

The main chamber—very large—consisted of a small, central, highly polished dancing floor, canopied far above by a circular dome of colored glass, glittering white or peach-pink by turns, and surrounded on all sides by an elevated platform or floor, two or three feet above it, crowded with tables ranged in circles on ascending steps, so that all might see. Beyond the tables again was a wide, level, semi-circular promenade, flanked by ornate walls and divans and set with palms, marbles and intricate gilt curio cases. The general effect was one of intense light, pale, diaphanous silks of creams and lemon hues, white-and-gold walls, white tables,—a perfect glitter of glass mirrors, and picturesque paneling. Beyond the dancing-floor was a giant, gold-tinted, rococo organ, and within a recess in this, under the tinted pipes, a stringed orchestra. The place was crowded with women of the half-world, for the most part Germans—unusually slender, in the majority of cases delicately featured, as the best of these women are, and beautifully dressed. I say beautifully. Qualify it any way you want to. Put it dazzlingly, ravishingly, showily, outrageously—any way you choose. No respectable woman might come so garbed. Many of these women were unbelievably attractive, carried themselves with a grand air, pea-fowl wise, and lent an atmosphere of color and life of a very showy kind. The place was also crowded, I need not add, with young men in evening clothes. Only champagne was served to drink—champagne at twenty marks the bottle. Champagne at twenty marks the bottle in Berlin is high. You can get a fine suit of clothes for seventy or eighty marks.

The principal diversions here were dining, dancing, drinking. As at Monte Carlo and in Paris, you saw here that peculiarly suggestive dancing of the habitués and the more skilled performances of those especially hired for the occasion. The Spanish and Russian dancers, as in Paris, the Turkish and Tyrolese specimens, gathered from Heaven knows where, were here. There were a number of handsome young officers present who occasionally danced with the women they were escorting. When the dancing began the lights in the dome turned pink. When it ceased, the lights in the dome were a glittering white. The place is, I fancy, a rather quick development for Berlin. We drank champagne, waved away charmers, and finally left, at two or three o’clock, when the law apparently compelled the closing of this great central chamber; though after that hour all the patrons who desired might adjourn to an inner sanctum, quite as large, not so showy, but full of brilliant, strolling, dining, drinking life where, I was informed, one could stay till eight in the morning if one chose. There was some drunkenness here, but not much, and an air of heavy gaiety. I left thinking to myself, “Once is enough for a place like this.”

I went one day to Potsdam and saw the Imperial Palace and grounds and the Royal Parade. The Emperor had just left for Venice. As a seat of royalty it did not interest me at all. It was a mere imitation of the grounds and palace at Versailles, but as a river valley it was excellent. Very dull, indeed, were the state apartments. I tried to be interested in the glass ballrooms, picture galleries, royal auditoriums and the like. But alas! The servitors, by the way, were just as anxious for tips as any American waiters. Potsdam did not impress me. From there I went to Grunewald and strolled in the wonderful forest for an enchanted three hours. That was worth while.

* * * * *

The rivers of every city have their individuality and to me the Spree and its canals seem eminently suited to Berlin. The water effects—and they are always artistically important and charming—are plentiful.

The most pleasing portions of Berlin to me were those which related to the branches of the Spree—its canals and the lakes about it. Always there were wild ducks flying over the housetops, over offices and factories; ducks passing from one bit of water to another, their long necks protruding before them, their metallic colors gleaming in the sun.

You see quaint things in Berlin, such as you will not see elsewhere—the Spreewald nurses, for instance, in the Thiergarten with their short, scarlet, balloon skirt emphasized by a white apron, their triangular white linen head-dress, very conspicuous. It was actually suggested to me one day as something interesting to do, to go to the Zoological Gardens and see the animals fed! I chanced to come there when they were feeding the owls, giving each one a mouse,—live or dead, I could not quite make out. That was enough for me. I despise flesh-eating birds anyhow. They are quite the most horrible of all evoluted specimens. This particular collection—eagles, hawks, condors, owls of every known type and variety, and buzzards—all sat in their cages gorging themselves on raw meat or mice. The owls, to my disgust, fixed me with their relentless eyes, the while they tore at the entrails of their victims. As a realist, of course, I ought to accept all these delicate manifestations of the iron constitution of the universe as interesting, but I can’t. Now and then, very frequently, in fact, life becomes too much for my hardy stomach. I withdraw, chilled and stupefied by the way strength survives and weakness goes under. And to think that as yet we have no method of discovering why the horrible appears and no reason for saying that it should not. Yet one can actually become surfeited with beauty and art and take refuge in the inartistic and the unlovely!

* * * * *

One of the Berliners’ most wearying characteristics is their contentious attitude. To the few, barring the women, to whom I was introduced, I could scarcely talk. As a matter of fact, I was not expected to. They would talk to me. Argument was, in its way, obviously an insult. Anything that I might have to say or suggest was of small importance; anything they had to say was of the utmost importance commercially, socially, educationally, spiritually,—any way you chose,—and they emphasized so many of their remarks with a deep voice, a hard, guttural force, a frown, or a rap on the table with their fists that I was constantly overawed.

Take this series of incidents as typical of the Berlin spirit: One day as I walked along Unter den Linden I saw a minor officer standing in front of a sentry who was not far from his black-and-white striped sentry-box, his body as erect as a ramrod, his gun “presented” stiff before him, not an eyelash moving, not a breath stirring. This endured for possibly fifty seconds or longer. You would not get the importance of this if you did not realize how strict the German military regulations are. At the sound of an officer’s horn or the observed approach of a superior officer there is a noticeable stiffening of the muscles of the various sentries in sight. In this instance the minor officer imagined that he had not been saluted properly, I presume, and suspected that the soldier was heavy with too much beer. Hence the rigid test that followed. After the officer was gone, the soldier looked for all the world like a self-conscious house-dog that has just escaped a good beating, sheepishly glancing out of the corners of his eyes and wondering, no doubt, if by any chance the officer was coming back. “If he had moved so much as an eyelid,” said a citizen to me, emphatically and approvingly, “he would have been sent to the guard-house, and rightly. Swine-hound! He should tend to his duties!”

Coming from Milan to Lucerne, and again from Lucerne to Frankfort, and again from Frankfort to Berlin, I sat in the various dining-cars next to Germans who were obviously in trade and successful. Oh, the compact sufficiency of them! “Now, when you are in Italy,” said one to another, “you see signs—‘French spoken,’ or ‘English spoken’; not ‘German spoken.’ Fools! They really do not know where their business comes from.”

On the train from Lucerne to Frankfort I overheard another sanguine and vigorous pair. Said one: “Where I was in Spain, near Barcelona, things were wretched. Poor houses, poor wagons, poor clothes, poor stores. And they carry English and American goods—these dunces! Proud and slow. You can scarcely tell them anything.”

“We will change all that in ten years,” replied the other. “We are going after that trade. They need up-to-date German methods.”

In a café in Charlottenberg, near the Kaiser-Friedrich Gedächtnis-Kirche, I sat with three others. One was from Leipzig, in the fur business. The others were merchants of Berlin. I was not of their party, merely an accidental auditor.

“In Russia the conditions are terrible. They do not know what life is. Such villages!”

“Do the English buy there much?”

“A great deal.”

“We shall have to settle this trade business with war yet. It will come. We shall have to fight.”

“In eight days,” said one of the Berliners, “we could put an army of one hundred and fifty thousand men in England with all supplies sufficient for eight weeks. Then what would they do?”

Do these things suggest the German sense of self-sufficiency and ability? They are the commonest of the commonplaces.

During the short time that I was in Berlin I was a frequent witness of quite human but purely Teutonic bursts of temper—that rapid, fiery mounting of choler which verges apparently on a physical explosion,—the bursting of a blood vessel. I was going home one night late, with Herr A., from the Potsdamer Bahnhof, when we were the witnesses of an absolutely magnificent and spectacular fight between two Germans—so Teutonic and temperamental as to be decidedly worth while. It occurred between a German escorting a lady and carrying a grip at the same time, and another German somewhat more slender and somewhat taller, wearing a high hat and carrying a walking-stick. This was on one of the most exclusive suburban lines operating out of Berlin.

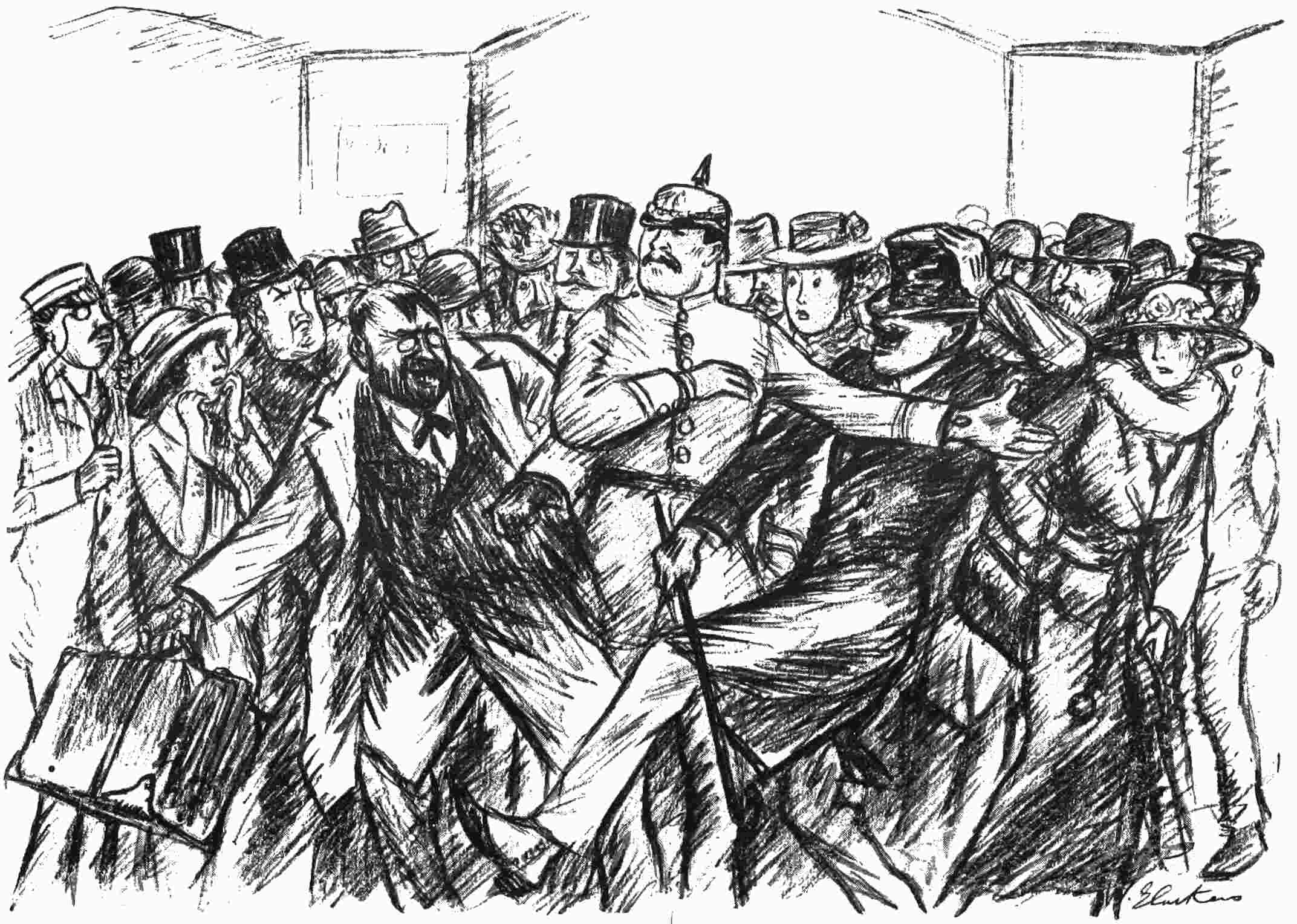

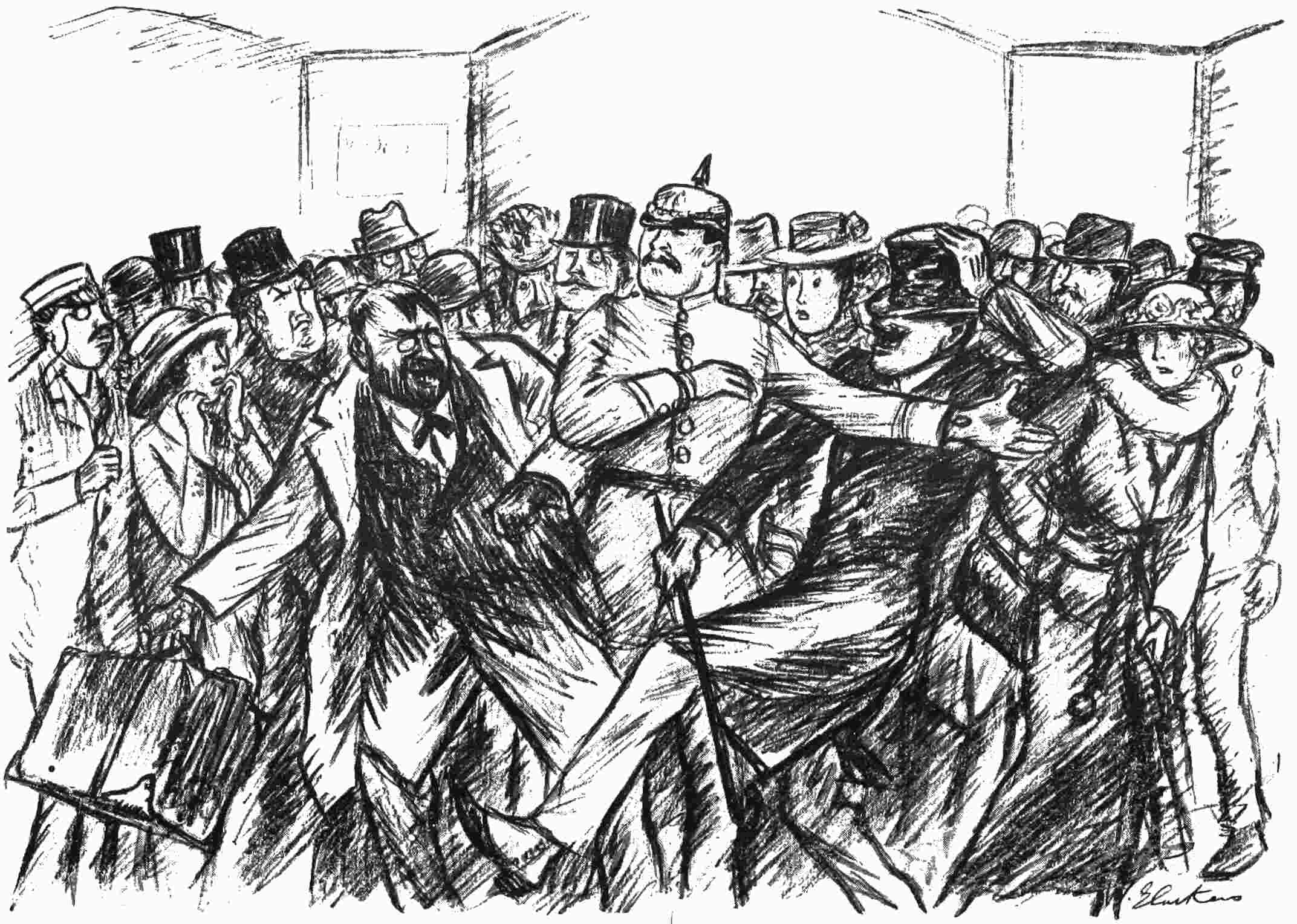

Teutonic bursts of temper

It appears that the gentleman with the high hat and cane, in running to catch his train along with many others, severely jostled the gentleman with the lady and the portmanteau. On the instant, an absolutely terrific explosion! To my astonishment—and, for the moment, I can say my horror—I saw these two very fiercely attack each other, the one striking wildly with his large portmanteau, the other replying with lusty blows of his stick, a club-like affair which fell with hard whacks on his rival’s head. Hats were knocked off, shirt-fronts marked and torn; blood began to flow where heads and faces were cut severely, and almost pandemonium broke loose in the surrounding crowd.

Fighting always produces an atmosphere of intensity in any nationality, but this German company seemed fairly to coruscate with anguish, wrath, rage, blood-thirsty excitement. The crowd surged to and fro as the combatants moved here and there. A large German officer, his brass helmet a welcome shield in such an affair, was brought from somewhere. Such noble German epithets as “Swine-hound!” “Hundsknochen!” (dog’s bone), “Schafskopf!” (sheep’s head), “Schafsgesicht!” (sheep-face), and even more untranslatable words filled the air. The station platform was fairly boiling with excitement. Husbands drove their wives back, wives pulled their husbands away, or tried to, and men immediately took sides as men will. Finally the magnificent representative of law and order, large and impregnable as Gibraltar, interposed his great bulk between the two. Comparative order was restored. Each contestant was led away in an opposite direction. Some names and addresses were taken by the policeman. In so far as I could see no arrests were made; and finally both combatants, cut and bleeding as they were, were allowed to enter separate cars and go their way. That was Berlin to the life. The air of the city, of Germany almost, was ever rife with contentious elements and emotions.

I should like to relate one more incident, and concerning quite another angle of Teutonism. This relates to German sentiment, which is as close to the German surface as German rage and vanity. It occurred in the outskirts of Berlin—one of those interesting regions where solid blocks of gold- and silver-balconied apartment houses march up to the edge of streetless, sewerless, lightless green fields and stop. Beyond lie endless areas of truck gardens or open common yet to be developed. Cityward lie miles on miles of electric-lighted, vacuum-cleaned, dumb-waitered and elevator-served apartments, and, of course, street cars.

I had been investigating a large section of land devoted to free (or practically free) municipal gardens for the poor, one of those socialistic experiments of Germany which, as is always the way, benefit the capable and leave the incapable just where they were before. As I emerged from a large area of such land divided into very small garden plots, I came across a little graveyard adjoining a small, neat, white concrete church where a German burial service was in progress. The burial ground was not significant or pretentious—a poor man’s graveyard, that was plain. The little church was too small and too sectarian in its mood, standing out in the wind and rain of an open common, to be of any social significance. Lutheran, I fancied. As I came up a little group of pall-bearers, very black and very solemn, were carrying a white satin-covered coffin down a bare gravel path leading from the church door, the minister following, bareheaded, and after him the usual company of mourners in solemn high hats or thick black veils, the foremost—a mother and a remaining daughter I took them to be—sobbing bitterly. Just then six choristers in black frock coats and high hats, standing to one side of the gravel path like six blackbirds ranged on a fence, began to sing a German parting-song to the melody of “Home Sweet Home.” The little white coffin, containing presumably the body of a young girl, was put down by the grave while the song was completed and the minister made a few consolatory remarks.

I have never been able, quite, to straighten out for myself the magic of what followed—its stirring effect. Into the hole of very yellow earth, cut through dead brown grass, the white coffin was lowered and then the minister stood by and held out first to the father and then to the mother and then to each of the others as they passed a small, white, ribbon-threaded basket containing broken bits of the yellow earth intermixed with masses of pink and red rose-leaves. As each sobbing person came forward he, or she, took a handful of earth and rose leaves and let them sift through his fingers to the coffin below. A lump rose in my throat and I hurried away.