CHAPTER XXXI

IN WHICH YOU READ OF THE GLORIOUS CAVERNS OF WHITE MARBLE FRONTING ON THE WONDERFUL RIVER.—IN THE TROPICS OF THE UNDER WORLD.—HOW WE CAME UPON A SOLITARY WANDERER ON THE BANKS OF THE RIVER.—MY CONVERSATION WITH HIM, AND MY JOY AT FINDING MYSELF IN THE LAND OF THE RATTLEBRAINS, OR HAPPY FORGETTERS.—BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THEM.

With every turn in the winding way that skirted the white shores of this wonderful stream, its swarms of light-emitting animals lent it a new beauty; for as the day advanced—if I may so express it—they lifted their glowing bodies nearer and nearer to the surface, until now the river shone like molten silver; and as the sheer walls of rock on the opposite bank held set in them vast slabs of mica, the effect was that these gigantic natural mirrors reflected the glowing stream with startling fidelity, and threw the flood of soft light in dazzling shimmer against the fantastic portals of the white marble caverns on this side of the stream. It was a scene never to forget, and again and again I paused in silent wonder to feast my eyes upon some newly discovered beauty. Now, for the first, I noted that every white marble basin of cove and inlet was filled with a different glow, according to the nature of the tiny phosphorescent animals which happened to fill its waters,—one being a delicate pink, another a glorious red, the third a deep rich purple, the fourth a soft blue, the fifth a golden yellow, and so on, the charm of each tint being greatly enhanced by the snowy whiteness of these marble basins, through which long lines of curious fish scaled in hues of polished gold and silver swam slowly along, turning up their glorious sides to catch the full splendor of the light reflected from the mica mirrors. And now the chilly breath of King Gelidus’ domain no longer filled the air. I stood in the tropics of the under world, so to speak; and but one thing was lacking to make my enjoyment of this fairy region complete, and that was some one to share it with me.

True, Bulger had an idea of its beauty, for he testified his happiness at being once more in a warm land by executing some mad capers for my amusement, and by scampering along the shore of the glowing river and barking at the stately fish as they slowly fanned the water with their many colored fins; but I must admit that I longed for the Princess Schneeboule to keep me company. But it was a rash wish; for the warm air would have thrown her into convulsions of fear, and she would have preferred to meet her death in the cool river rather than attempt to breathe such a fiery atmosphere. By this time I had advanced several miles along the white shores of the glowing stream, and, feeling somewhat fatigued, I was about to sit down on the jutting edge of a natural bench of rock, which seemed almost placed on the river banks by human hands for human forms to rest upon and watch the wonderful play of tints and hues in this wide sweeping inlet, when, to my amazement, I saw that a human creature was already sitting there.

His eyes were fixed upon the water, and methought that his face, which was gentle and placid, wore a tired look. Certainly he was plunged into such deep meditation that he either took or feigned to take no notice of my approach. Bulger was inclined to dash forward and attract his attention by a string of earsplitting barks, but I shook my head. This wanderer along the glowing stream of day wore rather a graceful cloak-like garment, woven of some substance that shimmered in the light, and so I concluded that it must be mineral wool. His head was bare, and so were his legs to the knees, his feet being shod with white metal sandals tied on with what looked like leathern thongs. All in all, he had a friendly though somewhat peculiar look about him, and his attitude struck me as being that of a person either plunged into deep thought, or possibly listening for some anxiously expected signal. At any rate, accustomed as I was to meet all sorts of people on my travels in the four corners of the globe, I determined to make bold enough to interrupt the gentleman’s meditations and wish him good-morrow.

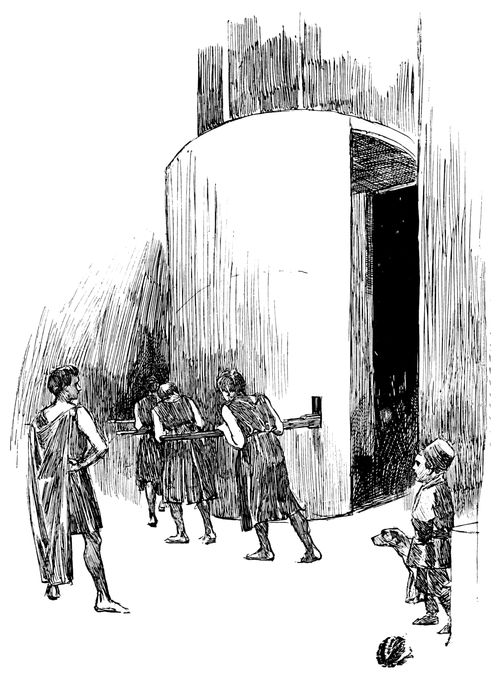

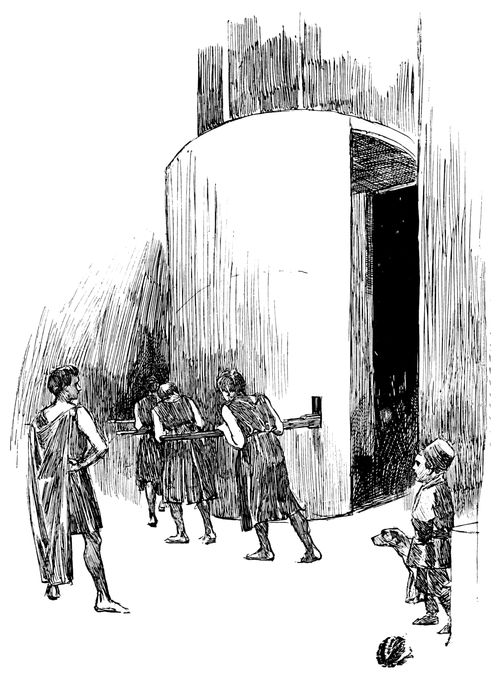

THROUGH THE REVOLVING DOOR.

“Whom have I the pleasure of meeting in this beautiful section of the World within a World?”

The man looked at me in a dazed sort of way and replied,—

“I really don’t know, I’m happy to say.”

“But, sir, thy name!” I insisted.

“Forgot it years ago,” was his remarkable answer.

“But surely, sir,” I exclaimed rather testily, “thou art not the sole inhabitant of this beautiful under world,—thou hast kinsman, wife, family?”

“Ay, gentle stranger,” he replied in slow and measured tones, “there are people farther along the shore, and they are good, dear souls, although I have forgotten their names, and I have, too, a very faint recollection that two of those people are sons of mine. Stop! no, their names are gone from me too, I forgot them the day my own name slipped from my mind!” and as he uttered these words he threw his head back with a sudden jerk and I heard a strange click inside of it, as if something had slipped from its place, and that instant a mysterious expression used by that Master of Masters, Don Fum, flashed through my mind.

Rattlebrains! Yes, that was it; and now I felt sure that I was standing in the presence of one of the curious folk inhabiting the World within a World, to whom Don Fum had given the strange name of Rattlebrains, or Happy Forgetters.

I was so delighted that I could barely keep myself from rushing up to this gentle-visaged and mild-mannered person, whose head had just given forth the sharp click, and grasping him by the hand. But I feared to shock him by such a friendly greeting, and so I contented myself with crying out,—

“Sir, thou seest before thee none other than the famous traveller, Baron Sebastian von Troomp!” but to my great amazement and greater chagrin he simply turned his strange eyes, with the far-away look, upon me for an instant, and then resumed his contemplation of the beautifully tinted sheet of water, as if I hadn’t opened my mouth. It was the most extraordinary treatment that I had experienced since my descent into the under world, and I was upon the point of resenting it, as became a true knight and especially a von Troomp, when Don Fum’s brief description of the Rattlebrains, or Happy Forgetters, flitted through my mind.

Said he, “By the exercise of their strong wills they have been busy for ages striving to unload their brains of the to them now useless stock of knowledge accumulated by their ancestors, and the natural consequence has been that the brains of these curious folk, who call themselves the Happy Forgetters, relieved of all labor and strain of thought, have absolutely shrunken rather than increased in size, so that with many of the Happy Forgetters their brains are like the shrivelled kernel of a last year’s nut and give forth a sharp click when they move their heads suddenly with a jerk, as is often their wont, for they take great pride in proving to the listener that they deserve the name of Rattlebrain.

“Nor do I need remind thee, O reader,” concluded Don Fum, in his celebrated work on the “World within a World,” “that the chiefest among the Happy Forgetters is the man whose head gives forth the loudest and sharpest click; for he it is who has forgotten most.”

You can have but a faint idea, dear friends, of my delight at the prospect of spending some time among these curious people—people who look with absolute dread upon knowledge as the one thing necessary to get rid of before happiness can enter the human heart.

No joy can equal the Happy Forgetter’s when, upon clasping a friend’s hand, he finds that he has forgotten his very name; and no day is well spent in this land at the close of which the inhabitant may not exclaim,—

“This day I succeeded in forgetting something that I knew yesterday!”

At last the Happy Forgetter rose from his seat and calmly walked away, without so much as wishing me good-day; but I was resolved not to be so easily gotten rid of, so I called after him in a loud voice, and Bulger, following my example, raised a racket at his heels, whereupon he faced about and remarked,—

“Beg pardon, I had quite forgotten thee, I’m happy to say, and thy name too, I’ve forgotten that; let me see, Art thou a radiate?” (One of the animals in the water.) I was more than half inclined to lose my temper at this slur, classing me, a back-boned animal, with a mere jelly-fish; but under all the circumstances I thought it best to control myself, for I could well imagine that from the size of my head and the utter absence of all click inside of it, I was not destined to be a very welcome visitor among the Happy Forgetters; and therefore, swallowing my injured feelings, I made a very low bow, and begged this curious gentleman to be kind enough to conduct me to his people—among whom I wished to abide for a few days.