CHAPTER XXXII

HOW WE ENTERED THE LAND OF THE HAPPY FORGETTERS.—SOMETHING MORE ABOUT THESE CURIOUS FOLK.—THEIR DREAD OF BULGER AND ME.—ONLY A STAY OF ONE DAY ACCORDED US.—DESCRIPTION OF THE PLEASANT HOMES OF THE HAPPY FORGETTERS.—THE REVOLVING DOOR THROUGH WHICH BULGER AND I ARE UNCEREMONIOUSLY SET OUTSIDE OF THE DOMAIN OF THE RATTLEBRAINS.—ALL ABOUT THE EXTRAORDINARY THINGS WHICH HAPPENED TO BULGER AND ME THEREAFTER.—ONCE MORE IN THE OPEN AIR OF THE UPPER WORLD, AND THEN HOMEWARD BOUND.

The Happy Forgetter pursued his way calmly along the winding path that skirted the glowing river, apparently, and no doubt really, unconscious of the fact that Bulger and I were following close at his heels. After half an hour or so of this silent tramp, he suddenly came to a standstill, and with his placid countenance turned toward the light seemed to be so far away in thought that for several moments I hesitated to address him. But as there were no signs of his showing any disposition to come to himself, I made bold to ask him the cause of the delay.

“I’m happy to say,” he remarked, without so much as deigning to turn his head, “that I’ve forgotten which of these two roads leads to the homes of our people.”

Well, this was a pleasant outlook to be sure, and, I don’t know what we should have done had not Bulger solved the difficulty for us by making choice of one of the paths and dashing on ahead with a bark of encouragement for us to follow.

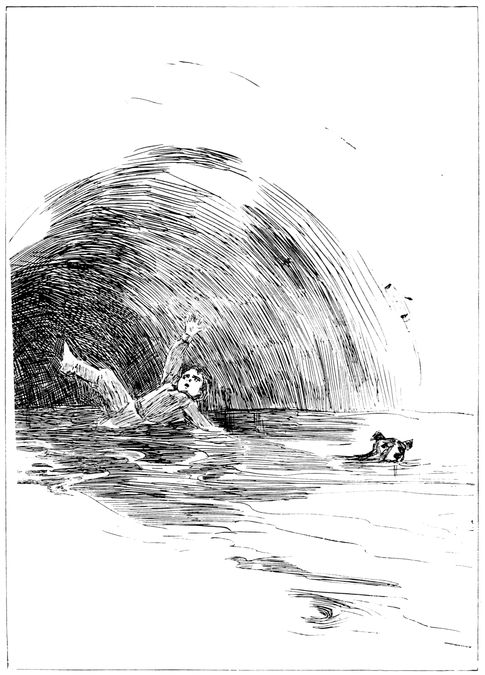

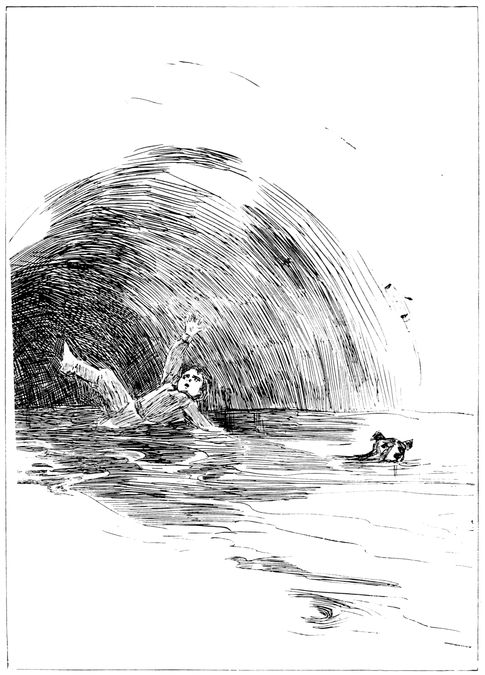

CAUGHT UP IN THE ARMS OF THE TORRENT.

When I assured the Happy Forgetter that he need have no fear as to the wisdom of the choice, he gave a start of almost horror at the information; for you must know, dear friends, that the Happy Forgetter has more dread of knowledge than we have of ignorance. To him it is the mother of all discontent, the source of all unhappiness, the cause of all the dreadful ills that have come upon the world, and the people in it.

“The world,” said one of the Happy Forgetters to me sadly, “was perfectly happy once, and man had no name for his brother, and yet he loved him even as the turtle-dove loves his mate, although he has no names to call her by. But, alas, one day this happiness came to an end, for a strange malady broke out among the people. They were seized with a wild desire to invent names for things; even many names for the same thing, and different ways of doing the same thing. This strange passion so grew upon them that they spent their lives in making them in every possible way harder to live. They built different roads to the same place, they made different clothes for different days, and different dishes for different feasts. To each child they gave two, three, and even four different names; and different shoes were fashioned for different feet, and one family was no longer satisfied with one drinking-gourd. Did they stop here?

“Nay, they now busied themselves learning how to make different faces to different friends, covering a frown with a smile, and singing gay songs when their hearts were sad. In a few centuries a brother could no longer read a brother’s face, and one-half the world went about wondering what the other half was thinking about; hence arose misunderstandings, quarrels, feuds, warfare. Man was no longer content to dwell with his fellow-man in the spacious caverns which kind nature had hollowed out for him, piercing the mountains with winding passages beside which his narrow streets dwindled to merest pathways.”

In the Land of the Happy Forgetters care never comes to trouble sleep, nor anxious thought to wear the dread mask of To-morrow!

Happy the day on which this child of nature might exclaim: “Since morn I’ve forgotten something! I’ve unloaded my mind! It’s one thought lighter than it was!”

He was the happiest of the Happy Forgetters who could honestly say, I know not thy name, nor when thou wast born, not where thou dwellest, nor who thy kinsmen are; I only know that thou art my brother, and that thou wilt not see me suffer if I should forget to eat, or perish of thirst if I forget to drink, and that thou wilt bid me close my eyes if I should forget that I had laid me down to sleep.

Bulger’s and my arrival in the Land of the Happy Forgetters filled the hearts of these curious folk with secret dread. At sight of my large head they all began to tremble like children in the dark stricken with fear of bogy or goblin, and with one voice they refused to permit me to sojourn a single brief half-hour among them; but gradually this sudden terror passed off a bit, and after a council held by a few of the younger men, whose brains as yet completely filled their heads, it was determined that I might bide for another day in their land, but that then the revolving door should be opened, and Bulger and I be thrust outside of their domain.

From what Don Fum had written about the Happy Forgetters, I knew only too well that it would be useless for me to attempt to reverse this decree; so I held my peace, except to thank them for this great favor shown me.

The daylight, if I may call it so, now began to wane, or rather the thousands of light-giving creatures swarming in the river now began to draw in their long tentacles, close their flower-like bodies, and slowly sink to the bottom of the stream. I was quite anxious to see whether the Happy Forgetters would make any attempt to light up their cavernous homes, or whether they would simply creep off to bed and sleep out the long hours of pitchy darkness. To my surprise, I now heard the clicking of flints on all sides, and in a moment or so a thousand or more great candles made of mineral wax with asbestos wicks were lighted, and the great chambers of white marble were soon aglow with these soft and steady flames.

The Happy Forgetters were strictly vegetable eaters, feeding upon the various fungous plants growing in these caverns in great profusion, together with a very nutritious and pleasant tasting jelly made from a hardened gum of vegetable origin which abounded in the crevices of certain rocks. There was still another source of food; namely, the nests of certain shellfish, which they built against the face of the rock, just above the surface of the river. These dissolved in boiling water made an excellent broth, very much like the soup from edible birds’ nests.

The clothes worn by the Happy Forgetters were entirely woven from mineral wool, which in these caverns gave a long and strong fibre of astonishing softness. The Rattlebrains were tolerably good metal-workers too, but contented themselves with fashioning only such articles as were actually necessary for daily use. Their beds were stuffed with dried seaweed and lichens, and Bulger and I passed a very comfortable night.

As I was forbidden to speak aloud, to ask a question, or to walk abroad unless in company with one of the selectmen, I was not sorry when the moment came for the revolving door to be opened. The Happy Forgetters had been led to believe that Bulger and I were a thousand times more dangerous than scaly monsters or black-winged vampires, and hence they held themselves aloof from us, the children hiding behind their mothers, and the mothers peering through crack and crevice at us.

The size of my head inspired them with a nameless dread, and even the half-a-dozen of the younger and more courageous drew aside instinctively to let me pass.

For the first time in my life I was an object of horror to my fellow-creatures, but I had no hard thoughts against them! Timid children of nature that they were, to them I was as terrible an object as the torch-armed demon of destruction would be to us were he let loose in one of our fair cities of the upper world.

And now the guard of Happy Forgetters had halted in front of what seemed to me to be a huge cask fashioned of solid marble, and set one-half within the white wall of the cavern to which they had led me. But on second glance I saw that there was a row of square holes around its bulge, like those in the top of a capstan.

The Happy Forgetters now disappeared for a moment, and when they joined me again each bore in hand a metal bar, the end of which he set in one of these holes, and then at a signal from the leader the huge half-circle of marble began to turn noiselessly around, exactly like a capstan. As each man’s lever came to the wall, he shifted it to the front again. Suddenly, to my amazement, I saw that the great marble cask was hollow, like a sentry box; and you may judge of my feelings, dear friends, upon being politely requested to step inside.

Did I refuse to obey?

Not I. It would have been useless, for was not the whole tribe of Rattlebrains there to lay hands upon me and thrust me in?

So taking off my hat and making a low bow to the little group of Happy Forgetters, I stepped within the hollow cask and Bulger did the same; but not with so good a grace as his master, for, casting an angry glance at the inhospitable dwellers in these chambers of white marble, he growled and laid bare his teeth to show his contempt for them.

Now the great marble cask began to revolve the other way and in a moment it was back in place again.

I heard several sharp clicks as if a number of huge spring latches had snapped into place, and then all was silent as the tomb, and I had almost said as dark too; but no, I could not say that, for I looked out into a low tunnel which ran past the niche in which Bulger and I were standing, and to my more than wonder it was dimly lighted.

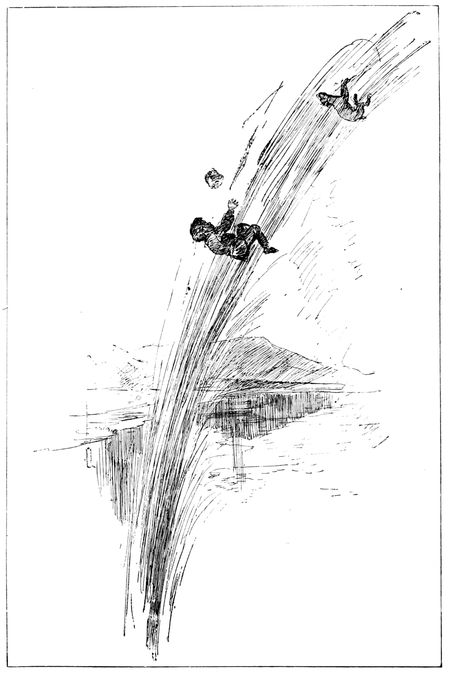

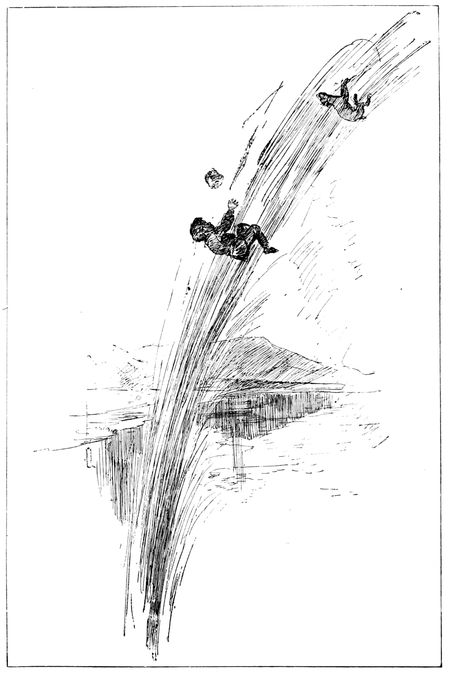

HURLED OUT IN THE SUNSHINE.

I stepped out into it; it was as round as a cannon bore and just high enough for me to stand erect; and now I discovered whence the light proceeded. In the cracks and crevices of its walls grew vast masses of those delicate light-giving fungous rootlets, the glow of which was so strong that I had no difficulty in reading the writing on my tablets; in fact, I stood there for several minutes making entries by the light of these bunches of glowing rootlets.

Then the thought dashed through my mind,—

“Which way shall I turn, to the right or to the left?”

Bulger comprehended the cause of my vacillation and made haste to come to my rescue. After sniffing the air, first in one direction and then in the other, he chose the right hand, and I followed without a thought of questioning his wisdom. Strange to say, he had not advanced more than a few hundred rods before I noticed that there was a strong current of air blowing through the tunnel in the direction Bulger had taken.

Every moment it increased in violence, fairly lifting us from our feet and bearing us along through this narrow bore made by nature’s own hands and lighted too by lamps of her own fashioning. The motion of the air through this vast pipe caused bursts of mighty tones as if peeled forth by some gigantic organ played by giant hands. It was strange, but yet I felt no terror as I listened to this unearthly music, although its depth of tone jarred painfully upon my ear-drums.

By the dim light of the luminous rootlets, I could see Bulger just ahead of me, and I was content. No shiver of fear ran down my back, or robbed my limbs of their full power to resist the ever-increasing pressure of the air. But as it grew stronger and stronger, half of my own accord and half because Bulger set the example, I broke into a run. Our pace once quickened it was impossible for me to slow up again. On, on, in a mad race, my feet scarcely touching the bottom of the tunnel, I sped along, while the great pipe through which I was borne on the very wings of the gale sent forth its deep and majestic peal.

There was something strangely and mysteriously exciting in this race, and all that kept me from enjoying it to my full bent was the thought that a sudden increase in the violence of the blast might toss me violently on my face and possibly break an arm for me or injure me in some serious way.

All at once the deep pealing forth of the organ-like tone ceased, and in its stead came the awful sound of rushing water. Before I had time to think, it was upon me, striking me like a terrific blow from some gigantic fist wearing a boxing-glove. The next instant I was caught up like a cork on a mountain torrent, swayed from side to side, twisted, turned, sucked down and cast up again, whirled over and over, tossed and tumbled, rolled along like a wheel, my arms and legs the spokes!

Wonderful to relate, I did not lose consciousness as this terrible current shot me like a stick of timber through a flume, whither I knew not, only that the speed and volume went ever on increasing until at last the tumultuous torrent filled the tunnel, and robbed me of light, of breath, of life, of everything, including my faithful and loving Bulger!

How long it lasted—this fearful ride in the arms of these mad waters, rushing as if for life or death through this narrow bore—I know not; I only know that my ears were suddenly assailed with a mighty whizz and rush of water as through the nozzle of some gigantic hose, and that I was shot out into the glorious sunshine, out into the grand, free, open air of the upper world, and sent flying up toward the dear, blue sky with its flecks of fleecy cloudlets, and Bulger some twenty feet ahead of me, and that then, with a gracefully curved flight through the soft and balmy air of harvest time, we both were gently dropped into a quiet little lake nestled at the foot of a hillside yellow with ripened corn. In a moment or so we had swum ashore. Bulger wanted to halt and shake the water from his thick coat, but I couldn’t wait for that. Wet as he was, I clasped him to my heart while he showered caresses on me. But not a word was said, not a sound was uttered. We were both of us too happy to speak, and if you have ever been in that state, dear friends, you know how it feels.

I can’t describe it to you.

At this moment some men and boys clad in the garb of the Russian peasant came racing across the fields to see what I was about, no doubt, for I had stripped off my heavy outside clothing, and was spreading it out in the sun to dry.

Upon sight of these red-cheeked children of the upper world I was so overcome with joy that for a minute or so I couldn’t get a syllable across my lips, but making a great effort I cried out,—

“Fathers! Brothers! Where am I? Speak! dear souls!”

“In north-eastern Siberia, little soul,” replied the eldest of the party, “not far from the banks of the Obi; but whence comest thou? By Saint Nicholas, I believe thou wast spit out of the spouting well! What art thou doing here alone?”

I paid no attention to the question. I was thinking of something else of more importance to me, to wit: my splendid achievement, the marvellous underground journey I had just completed, fully five hundred miles in length, passing completely under the Ural Mountains! After a short stay at the nearest village, I engaged the best guide that was to be had, and crossing the Urals by the pass in the most direct line, re-entered Russia and made haste to join the first government train on its way to St. Petersburg.

Having despatched an avant courier with letters to my beloved parents, informing them of my good health and whereabouts, I passed several weeks very pleasantly in the Russian capital, and then by easy stages set out for home.

The elder baron came as far as Riga to meet me, and brought me the best of news from Castle Trump, that my dear mother was in perfect health, and that she and every man, woman, and child in and about the castle were anxiously waiting to give me a real German welcome back home again. And here, dear friends, mit herzlichen Grüsse, Bulger and I take our leave of you.