CHAPTER VIII.

The marriage before the mayor had taken place on the Thursday. On the Saturday morning, as early as a quarter past ten, some ladies were already waiting in the Josserands’ drawing-room, the religious ceremony being fixed for eleven o’clock, at Saint-Roch. There were Madame Juzeur, always in black silk; Madame Dambreville, tightly laced in a costume of the color of dead leaves; and Madame Duveyrier, dressed very simply in pale blue. All three were conversing in low tones amongst the scattered chairs; whilst Madame Josserand was finishing dressing Berthe in the adjoining room, assisted by the servant and the two bridesmaids, Hortense and little Campardon.

“Oh! it is not that,” murmured Madame Duveyrier; “the family is honorable. But, I admit, I rather dreaded on my brother Auguste’s account the mother’s domineering spirit. One cannot be too careful, can one?”

“No doubt,” said Madame Juzeur; “one not only marries the daughter, one often marries the mother as well, and it is very unpleasant when the latter interferes in the home.”

This time Angèle and Hortense opened the folding doors wide so that the bride should not catch her dress in anything; and Berthe appeared in a white silk dress, all gay with white flowers, with a white wreath, a white bouquet, and a white garland, which crossed the skirt, and was lost in the train in a shower of little white buds. She looked charming amidst all this whiteness, with her fresh complexion, her golden hair, her laughing eyes, and her candid mouth of an already enlightened girl.

“Oh! delicious!” exclaimed the ladies.

They all embraced her with an air of ecstasy. The Josserands, at their wits’ end, not knowing where to obtain the two thousand francs which the wedding would cost them, five hundred francs for dress, and fifteen hundred francs for their share of the dinner and ball, had been obliged to send Berthe to Doctor Chassagne’s to see Saturnin, to whom an aunt had just left three thousand francs; and Berthe, having obtained permission to take her brother out for a drive, by way of amusing him, had smothered him with caresses in the cab, and had then gone with him for a minute to the notary, who was unaware of the poor creature’s condition, and who had everything ready for his signature. The silk dress and the abundance of flowers surprised the ladies, who were reckoning up the cost whilst giving vent to their admiration.

“Perfect! in most exquisite taste!”

Madame Josserand appeared, beaming, in a mauve dress of an unpleasant hue, which made her look taller and rounder than ever, with the majesty of a tower. She fumed about Monsieur Josserand, called to Hortense to find her shawl, and vehemently forbade Berthe to sit down.

“Take care, you will crush your flowers!”

“Do not worry yourself,” said Clothilde, in her calm voice. “We have plenty of time. Auguste is coming for us.”

They were all waiting in the drawing-room, when Théophile abruptly burst in, his dress-coat askew, his white cravat tied like a piece of cord, and without his hat. His face, with its few hairs and bad teeth, was livid; his limbs, like an ailing child’s, were trembling with fury.

“What is the matter with you?” asked his sister, in amazement.

“The matter is—the matter is——”

But a fit of coughing interrupted him, and he stood there for a minute, choking, spitting in his handkerchief, and enraged at being unable to give vent to his anger. Valérie looked at him, confused, and warned by a sort of instinct. At length, he shook his fist at her, without even noticing the bride and the other ladies around him.

“Yes, whilst looking everywhere for my necktie, I found a letter in front of the wardrobe.”

He crumpled a piece of paper between his febrile fingers. His wife had turned pale. She realized the situation; and, to avoid the scandal of a public explanation, she passed into the room that Berthe had just left.

“Ah! well,” said she, simply, “I prefer to leave if he is going mad.”

“Let me alone!” cried Théophile to Madame Duveyrier, who was trying to quiet him. “I intend to confound her. This time I have proof, and there is no doubt, oh, no! It shall not pass off like that, for I know him——”

His sister had seized him by the arm, and squeezing it, shook him authoritatively.

“Hold your tongue! don’t you see where you are? This is not the proper time, understand!”

But he started off again:

“It is the proper time! I don’t care a hang for the others. So much the worse that it happens to-day! It will serve as a lesson to every one.”

However, he lowered his voice, his strength failing him, he had dropped onto a chair, ready to burst into tears. An uncomfortable feeling had invaded the drawing-room. Madame Dambreville and Madame Juzeur had politely gone to the other end of the apartment, and pretended not to understand. Madame Josserand, greatly annoyed at an adventure, the scandal of which would cast a gloom over the wedding, had passed into the bed-room to cheer up Valérie. As for Berthe, who was studying her wreath before the looking-glass, she had not heard anything. Therefore, she questioned Hortense in a low voice. They whispered together; the latter indicated Théophile with a glance, and added some explanations, while pretending to arrange the fall of the veil.

“Ah!” simply said the bride, with a chaste and amused look, her eyes fixed on the husband, without the least sign of confusion in her halo of white flowers.

Clotilde softly asked her brother for particulars. Madame Josserand reappeared, exchanged a few words with her, and then returned to the adjoining room. It was an exchange of diplomatic notes. The husband accused Octave, that counter-jumper, whom he would chastise in church, if he dared to come there. He swore he had seen him the previous day with his wife on the steps of Saint-Roch; he had had a doubt before, but now he was sure of it—everything tallied, the height, the walk. Yes, madame invented luncheons with lady friends, or else she went inside Saint-Roch with Camille, through the same door as every one, as though to say her prayers; then leaving the child with the woman who let out the chairs, she would make off with her gentleman by the old way, a dirty passage, where no one would have gone to look for her. However, Valérie had smiled on hearing Octave’s name mentioned; never with that one, she pledged her oath to Madame Josserand, with nobody at all for the matter of that, she added, but less with him than with any one else; and, this time, with truth on her side, she, in her turn, talked of confounding her husband, by proving to him that the note was no more in Octave’s handwriting than that Octave was the gentleman of Saint-Roch. Madame Josserand listened to her, studying her with her experienced glance, and solely preoccupied with finding some means of helping her to deceive Théophile. And she gave her the very best advice.

“Leave all to me, don’t move in the matter. As he chooses, it shall he Monsieur Mouret, well! it shall be Monsieur Mouret. There is no harm in being seen on the steps of a church with Monsieur Mouret, is there? The letter alone is compromising. You will triumph when our young friend shows him a couple of lines of his own handwriting. Above all, say just the same as I say. You understand, I don’t intend to let him spoil such a day as this.”

When she returned into the room with Valérie, who was greatly affected, Théophile, on his side, was saying to his sister in a choking voice:

“I will do so for you, I promise not to disfigure her here, as you assure me it would scarcely be proper, on account of this wedding. But I cannot be answerable for what may take place at church. If the counter-jumper comes and beards me there, in the midst of my own family, I will exterminate them one after the other.”

Auguste, looking very correct in his black dress-coat, his left eye shrunk up, suffering from a headache which he had been dreading for three days past, arrived at this moment, accompanied by his father and his brother-in-law, both looking very solemn, to fetch his bride. There was a little jostling, for they had ended by being late.

At Saint-Roch the big double doors were opened wide. A red carpet covered the steps down to the pavement. It was raining; the May morning was very cold.

“Thirteen steps,” said Madame Juzeur in a low voice to Valérie, when they had passed through the doorway. “It is not a good sign.”

“Are you sure you have the ring?” inquired Madame Josserand of Auguste, who was seating himself with Berthe on the arm-chairs placed before the altar.

He had a fright, fancying he had forgotten it, then felt it in his waistcoat pocket. She had, however, not waited for his answer. Ever since she entered, she had been standing on tip-toe, searching the company with her glance. There were Trublot and Gueulin, both best men; Uncle Bachelard and Campardon, the bride’s witnesses; Duveyrier and Doctor Juillerat, the bridegroom’s witnesses, and all the crowd of acquaintances of whom she was proud. But she had just caught sight of Octave, who was assiduously opening a passage for Madame Hédouin, and she drew him behind a pillar, where she spoke to him in low and rapid tones. The young man, a look of bewilderment on his face, did not appear to understand. However, he bowed with an air of amiable obedience.

“It is settled,” whispered Madame Josserand in Valérie’s ear, returning and seating herself in one of the arm-chairs placed for the members of the family, behind those of Berthe and Auguste. Monsieur Josserand, the Vabres, and the Duveyriers were also there.

The organs were now giving forth scales of clear little notes, broken by big pants. There was quite a crush; the choir was filling up, and men remained standing in the aisles. The Abbé Mauduit had reserved to himself the joy of blessing the union of one of his dear penitents. When he appeared in his surplice, he exchanged a friendly smile with the congregation, every face there being familiar to him. Some voices commenced the Veni Creator, the organs resumed their song of triumph, and it was at this moment that Théophile discovered Octave, to the left of the chancel, standing before the chapel of Saint-Joseph.

His sister Clotilde tried to detain him.

“I cannot,” stammered he; “I will never submit to it.”

And he made Duveyrier follow him, to represent the family. The Veni Creator continued. A few persons looked round.

Théophile, who had talked of blows, was in such a state of agitation, when planting himself before Octave, that he was unable at first to say a word, vexed at being short, and raising himself up on tiptoe.

“Sir,” said he at length, “I saw you yesterday with my wife——”

But the Veni Creator was just coming to an end, and he was quite scared on hearing the sound of his own voice. Moreover, Duveyrier, very much annoyed by the incident, tried to make him understand that the time was badly chosen for an explanation. The ceremony had now begun before the altar. After addressing an affecting exhortation to the bride and bridegroom, the priest took the wedding-ring to bless it.

“Benedic, Domine Deus noster, annulum nuptialem hunc, quem nos in tuo nomine benedieimus——”

Then Théophile plucked up courage to repeat his words in a low voice:

“Sir, you were in this church yesterday with my wife.”

Octave, still bewildered by what Madame Josserand had said to him, and without having thoroughly understood her, related the little story, however, in an easy sort of way.

“Yes, I did indeed meet Madame Vabre, and we went and looked at the repairing of the Calvary which my friend Campardon is directing.”

“You admit it,” stammered the husband, again overcome with fury, “you admit it——”

Duveyrier was obliged to slap him on the shoulder to calm him. The shrill voice of one of the boy choristers was responding:

“Amen.”

“And you no doubt recognize this letter,” continued Théophile, offering a piece of paper to Octave.

“Come, not here!” said the counselor, thoroughly scandalized. “You are going out of your mind, my dear fellow.”

Octave unfolded the letter. The emotion had increased amongst the congregation. There were whisperings, and nudgings of elbows, and glancing over the tops of prayer-books; no one was now paying the least attention to the ceremony. The bride and bridegroom alone remained grave and stiff before the priest. Then Berthe, turning her head, caught sight of Théophile getting whiter and whiter as he addressed Octave; and, from that moment, her mind was absent—she kept casting bright side glances in the direction of the chapel of Saint-Joseph.

Meanwhile, the young man was reading in a low voice:

“My duck, what bliss yesterday! Tuesday next, in the confessional of the chapel of the Holy Angels.”

The priest, after having obtained from the bridegroom the “yes” of a serious man who signs nothing without reading it, had turned toward the bride.

“You promise and swear to be faithful to Monsieur Auguste Vabre in all things, like a true wife should be to her husband, in accordance with God’s commandment?”

But Berthe, having seen the letter, and full of the thought of the blows she was expecting would be given, was not listening, but was following the scene from beneath her veil. There was an awkward silence. At length she became aware that they were waiting for her.

“Yes, yes,” she hastily replied, in a happen-what-may manner.

The abbé followed the direction of her glance with surprise; and, guessing that something unusual was taking place in one of the aisles, he in turn became singularly absent-minded. The story had now circulated; every one knew it. The ladies, pale and grave, did not withdraw their eyes from Octave. The men smiled in a discreetly waggish way. And, whilst Madame Josserand reassured Madame Duveyrier, with slight shrugs of her shoulders, Valérie alone seemed to give all her attention to the wedding, beholding nothing else, as though overcome by emotion.

“My duck, what bliss yesterday—” Octave read again, affecting intense surprise.

Then, returning the letter to the husband, he said:

“I do not understand it, sir. The writing is not mine. See for yourself.”

And taking from his pocket a note-book in which he wrote down his expenses, like the careful fellow he was, he showed it to Théophile.

“What! not your writing!” stammered the latter. “You are making a fool of me; it must be your writing.”

The priest had to make the sign of the cross on Berthe’s left hand. His eyes elsewhere, he mistook the hand and made it on the right one.

“In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti.”

“Amen,” responded the boy chorister, also raising himself up to see.

In short, the scandal was prevented. Duveyrier proved to poor, bewildered Théophile that the letter could not have been written by Monsieur Mouret. It was almost a disappointment for the congregation. There were sighs, and a few hasty words exchanged. And when every one, still in a state of excitement, turned again toward the altar, Berthe and Auguste were man and wife, she without appearing to have been aware of what was going on, he not having missed a word the priest had uttered, giving his whole attention to the matter, only disturbed by his headache, which closed his left eye.

“The dear children!” said Monsieur Josserand, absorbed in mind and his voice trembling, to Monsieur Vabre, who ever since the commencement of the ceremony had been busy counting the lighted tapers, always making a mistake, and beginning his calculations over again.

“Admit nothing,” said Madame Josserand to Valérie, as the family moved toward the vestry after the mass.

In the vestry the married couple and their witnesses first of all wrote their signatures. They were kept waiting, however, by Campardon, who had taken some ladies to inspect the works at the Calvary, at the end of the choir, behind a wooden hoarding. He at length arrived, and, apologizing, proceeded to cover the register with a big flourish. The Abbé Mauduit had wished to honor the two families by handing round the pen himself, and pointing out with his finger the place where each one was to sign; and he smiled with his air of amiable, worldly tolerance in the center of the grave apartment, the woodwork of which retained a continual odor of incense.

“Well! mademoiselle,” said Campardon to Hortense, “does not all this make you long to do the same?”

Then he regretted his want of tact. Hortense, who was the elder sister, bit her lips. She was expecting to have a decisive answer from Verdier that evening at the ball, for she had been pressing him to choose between her and his creature. Therefore she replied in an unpleasant tone of voice:

“I have plenty of time. Whenever I think proper.”

And, turning her back on the architect, she attacked her brother Léon, who had only just arrived, late as usual.

“You are nice! papa and mamma are very pleased. Not even able to be in time when one of your sisters is being married! We were expecting you at least with Madame Dambreville.”

“Madame Dambreville does what she pleases,” said the young man curtly, “and I do what I can.”

A coolness had arisen between them. Léon considered that she was keeping him too long for her own use, and was weary of a connection the burden of which he had accepted in the sole hope of its leading to some grand marriage; and for a fortnight past he had been requesting her to keep her promises. Madame Dambreville, carried away by a passion of love, had even complained to Madame Josserand of what she termed her son’s crotchets.

“Yet a marriage is so soon settled!” said Madame Dambreville, without thinking of her words, and bestowing on him an imploring look to soften him.

“Not always!” retorted he, harshly.

And he went and kissed Berthe, then shook his new brother-inlaw’s hand, whilst Madame Dambreville turned pale with anguish, drawing herself up in her costume of the color of dead leaves, and smiling vaguely toward the persons who entered.

It was the procession of friends, of simple acquaintances, of all the guests gathered together in the church, which now passed through the vestry. The newly married couple, standing up, were continually distributing hand-shakes, and invariably with the same embarrassed and delighted air. The Josserands and the Duveyriers were not always able to go through the introductions. At times they looked at each other in surprise, for Bachelard had brought persons whom nobody knew, and who talked too loud. Little by little everything gave way to confusion; there was quite a crush, hands were held out over the heads, young girls squeezed between pot-bellied gentlemen, left pieces of their white skirts on the legs of these fathers, these brothers, these uncles, still sweating with some vice, enfranchised in a quiet neighborhood. Away from the crowd, Gueulin and Trublot were relating to Octave how Clarisse had almost been caught by Duveyrier the night before, and had now resigned herself to smothering him with caresses, so as to shut his eyes.

“Hallo!” murmured Gueulin, “he is kissing the bride; it must smell nice.”

Valérie, who kept Madame Juzeur near her to help her to keep her countenance, listened with emotion to the conciliatory words which the Abbé Mauduit also considered it his duty to address to her. Then, as they were at length leaving the church, she paused before the two fathers, to allow Berthe to pass on her husband’s arm.

“You ought to be satisfied,” said she to Monsieur Josserand, wishing to show how free her mind was. “I congratulate you.”

“Yes, yes,” declared Monsieur Vabre in his clammy voice, “it is a very great responsibility the less.”

And, whilst Trublot and Gueulin rushed about seeing all the ladies to the carriages, Madame Josserand, whose shawl attracted quite a crowd, obstinately insisted on remaining the last on the pavement, publicly to display her maternal triumph.

The repast that evening at the Hôtel du Louvre was likewise marred by Théophile’s unlucky affair. The latter was quite a plague, it had been the topic of conversation all the afternoon in the carriages during the drive in the Bois de Boulogne; and the ladies always came to this conclusion, that the husband ought at least to have waited until the morrow before finding the letter. None but the most intimate friends of both families sat down to table. The only lively episode was a speech from uncle Bachelard, whom the Josserands could not very well avoid inviting, in spite of their terror. He was drunk, indeed, as early as the roast: he raised his glass, and commenced with these words: “I am happy in the joy I feel,” which he kept repeating, unable to say anything further. The other guests smiled complacently. Auguste and Berthe, already worn out, looked at each other every now and then, with an air of surprise at seeing themselves opposite one another; and, when they remembered how this was, they gazed in their plates in a confused way.

Nearly two hundred invitations had been issued for the ball. The guests began to arrive as early as half-past nine. Three chandeliers lit up the large red drawing-room, in which only some seats along the wall had been left, whilst at one end, in front of the fireplace, the little orchestra was installed; moreover, a bar had been placed at the farthest end of an adjoining room, and the two families also had a small apartment into which they could retire.

As Madame Duveyrier and Madame Josserand were receiving the first arrivals, that poor Théophile, who had been watched ever since the morning, was guilty of a most regrettable piece of brutality. Campardon was asking Valérie to grant him the first waltz. She laughed, and the husband took it as a provocation.

“You laugh! you laugh!” stammered he. “Tell me who the letter is from? it must be from somebody, that letter must.”

He had taken the entire afternoon to disengage that one idea from the confusion into which Octave’s answers had plunged him. Now, he stuck to it: if it was not Monsieur Mouret, it was then some one else, and he demanded a name. As Valerie was walking off without answering him, he seized hold of her arm and twisted it spitefully, with the rage of an exasperated child, repeating the while:

“I’ll break it. Tell me, who is the letter from?”

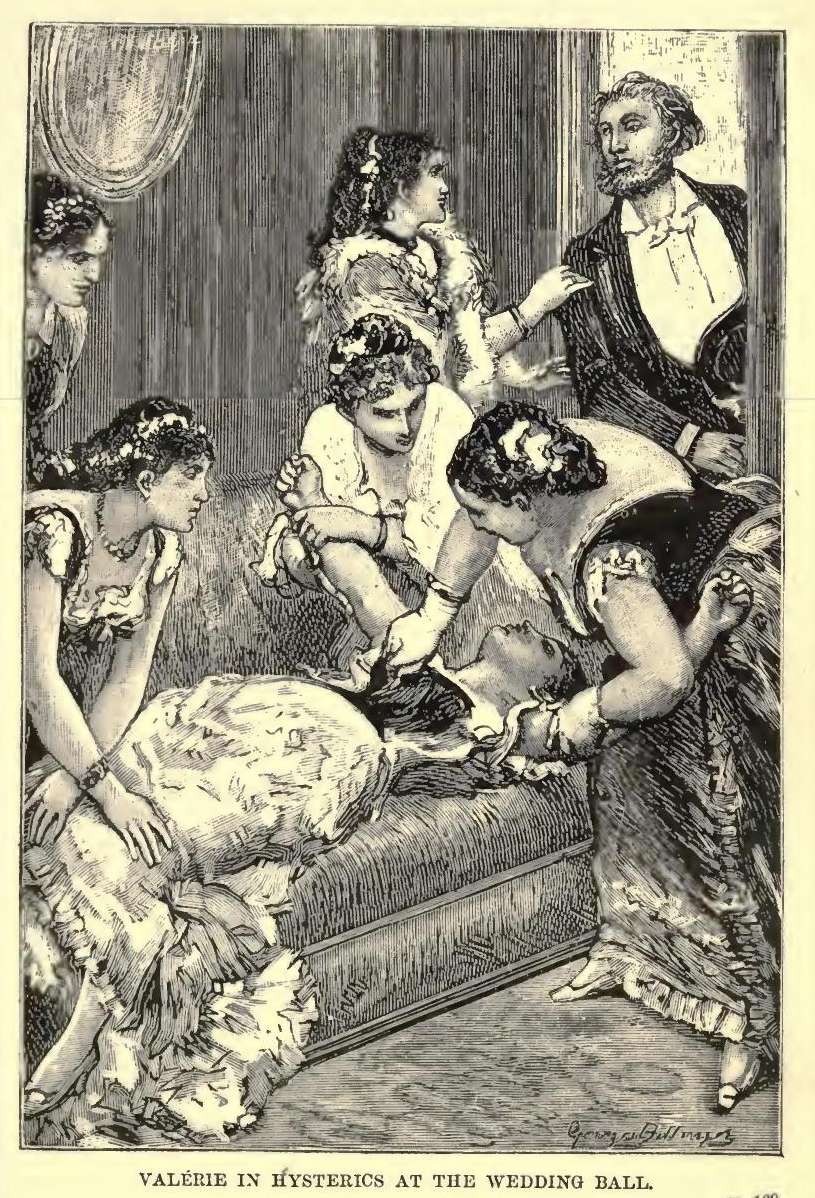

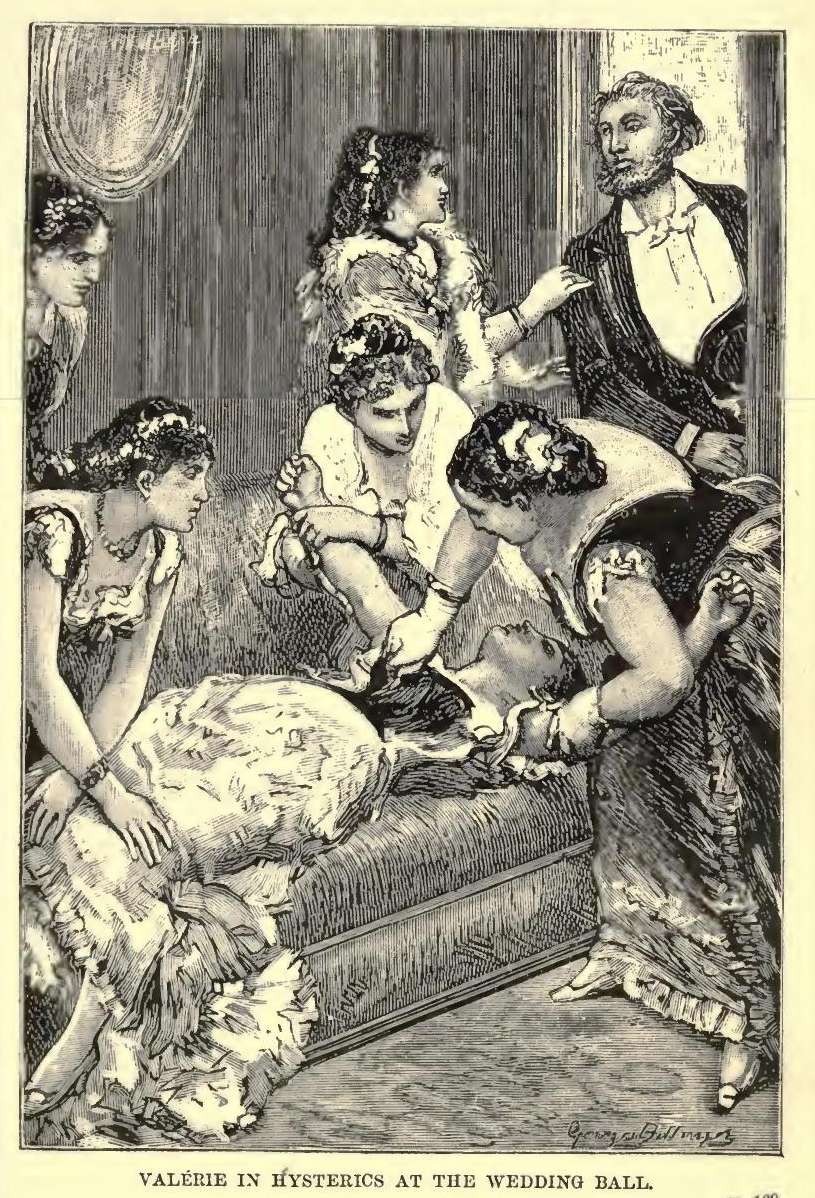

The young woman, frightened, and stifling a cry of pain, had become quite white. Campardon felt her abandoning herself against his shoulder, succumbing to one of those nervous attacks which would shake her for hours together. He had scarcely time to lead her into the apartment reserved for the two families, where he laid her on a sofa. Some ladies had followed him—Madame Juzeur, Madame Dambreville—who unlaced her, whilst he discreetly retired.

“Sir, I beg your pardon,” said Théophile, going up to Octave, whose eyes he had encountered when twisting his wife’s arm. “Every one in my place would have suspected you; is it not so? But I wish to shake hands with you, to prove to you that I admit myself to have been in the wrong.”

He shook hands with him, and led him one side, tortured by a necessity to unbosom himself, to find a confidant for the outpourings of his heart.

“Ah! sir, if I were to tell you——”

And he talked for a long while of his wife. When a young girl, she was delicate, it was said jokingly that marriage would set her right. She had not sufficient air in her parents’ shop, where, every evening for three months, she had appeared to him very nice, obedient, of a rather sad disposition, but charming.

“Well! sir, marriage did not set her right—far from it. After a few weeks she became terrible; we could no longer agree together. There were quarrels about nothing at all. Changes of temper at every minute—laughing, crying, without my knowing why. And absurd sentiments, ideas that would knock a person down, a perpetual mania for making people wild. In short, sir, my home has become a hell.”

“It is very remarkable,” murmured Octave, who felt a necessity for saying something.

Then, the husband, ghastly pale, and drawing himself up on his short legs, to override the ridiculous, came to what he called the wretched woman’s bad behavior. Twice he had suspected her; but he was too honorable; he could not retain such an idea in his head. This time, though, he was obliged to yield to evidence. It was not possible to doubt, was it? And, with his trembling fingers, he felt the pocket of his waistcoat which contained the letter.

“If she did it for money, I might understand it,” added he. “But they never gave her any; I am sure of that; I should know it. Then, tell me what it can be that she has in her skin? I am very nice myself; she has everything at home. I cannot understand it. If you can understand it, sir, explain it to me, I beg of you.”

“It is very curious, very curious,” repeated Octave, embarrassed by all these disclosures, and trying to make his escape.

But the husband, in a state of fever, and tormented by a want of certitude, would not let him go. At this moment, Madame Juzeur, reappearing, went and whispered a word to Madame Josserand, who was greeting the arrival of a big jeweler of the Palais-Royal with a grand curtesy; and she, quite upset, hastened to follow her.

“I think that your wife has a very violent attack,” observed Octave to Théophile.

“Never mind her!” replied the latter in a fury, vexed at not being ill, so as to be coddled up also; “she is only to pleased to have an attack! It always puts every one on her side. My health is no better than hers, yet I have never deceived her!”

Madame Josserand did not return. The rumor circulated among the intimate friends that Valérie was struggling in frightful convulsions. There should have been men present to hold her down; but, as they had been obliged to half undress her, they declined Trublot’s and Gueulin’s offers of assistance.

“Doctor Juillerat! where is Doctor Juillerat?” asked Madame Josserand, rushing back into the room.

The doctor had been invited, but no one had as yet seen him. Then she no longer strove to hide the slumbering rage which had been collecting within her since the morning. She spoke out before Octave and Campardon, without mincing her words.

“I am beginning to have enough of it. It is not very pleasant for my daughter, all this cuckoldom paraded before us!”

She looked about for Hortense, and at length caught sight of her talking to a gentleman, of whom she could only see the back, but whom she recognized by its breadth. It was Verdier. This increased her ill-humor. She sharply called the young girl to her, and, lowering her voice, told her that she would do better to remain at her mother’s disposal on such a day as that. Hortense did not listen to the reprimand. She was triumphant; Verdier had just fixed their marriage at two months from then, in June.

“Shut up!” said the mother.

“I assure you, mamma. He already sleeps out three nights a week so as to accustom the other to it, and in a fortnight he will stop away altogether. Then it will be all over, and I shall have him.”

“Shut up! I have already had more than enough of your romance! You will just oblige me by waiting near the door for Doctor Juillerat, and by sending him to me the moment he arrives. And, above all, not a word of all this to your sister!”

She returned to the adjoining room, leaving Hortense muttering that, thank goodness! she required no one’s approbation, and that they would all be nicely caught one day, when they saw her make a better marriage than the others. Yet, she went to the door, and watched for the doctor’s arrival.

The orchestra was now playing a waltz. Berthe was dancing with one of her husband’s young cousins, so as to dispose of the relations in turn. All the guests had an air of amusing themselves immensely, and expatiated before them on the liveliness of the ball. It was, according to Campardon, a liveliness of a good standard.

The architect, with an effusion of gallantry, concerned himself a great deal about Valérie’s condition, without, however, missing a dance. He had the idea to send his daughter Angèle for news in his name. The child, whose fourteen years had been burning with curiosity since the morning around the lady that every one was talking about, was delighted at being able to penetrate into the little room. And, as she did not return, the architect was obliged to take the liberty of slightly opening the door and thrusting his head in. He beheld his daughter standing up beside the sofa, deeply absorbed by the sight of Valérie, whose bosom, shaken by spasms, had escaped from the unhooked bodice. Protestations arose, the ladies called to him not to come in; and he withdrew, assuring them that he merely wished to know how she was getting on.

“She is no better, she is no better,” said he, in a melancholy way to the persons who happened to be near the door. “There are four of them holding her. How strong a woman must be, to be able to bound about like that without hurting herself!”

But Doctor Juillerat quickly crossed the ball-room, accompanied by Hortense, who was explaining matters to him. Madame Duveyrier followed them. Some persons showed their surprise, more rumors circulated. Scarcely had the doctor disappeared than Madame Josserand left the little room with Madame Dambreville. Her rage was increasing; she had just emptied two water bottles over Valerie’s head; never before had she seen a woman as nervous as that. Then she had decided to make the round of the ball-room, so as to stop all remarks by her presence. Only, she walked with such a terrible step, she distributed such sour smiles, that every one behind her was let into the secret.

Madame Dambreville did not leave her. Ever since the morning she had been speaking to her of Léon, making vague complaints, trying to bring her to speak to her s