CHAPTER IX.

Two days later, toward seven o’clock, as Octave arrived at the Campardons’ for dinner, he found Rose by herself, dressed in a cream-color dressing-gown, trimmed with white lace.

“Are you expecting any one?” asked he.

“No,” replied she, rather confused. “We will have dinner directly Achille comes in.”

The architect was abandoning his punctual habits; was never there at the proper time for his meals, arrived very red in the face, with a wild expression, and cursing business. Then he went off again every evening, on all kinds of pretexts, talking of appointments at cafés, inventing distant meetings. Octave, on these occasions, would often keep Rose company till eleven o’clock, for he had understood that the husband had him there to board to amuse his wife, and she would gently complain, and tell him her fears: ah! she left Achille very free, only she was so anxious when he came home after midnight!

“Do you not think he has been rather sad lately?” asked she, in a tenderly frightened tone of voice.

The young man had not noticed it.

“I think he is rather worried, perhaps. The works at Saint-Roch cause him some anxiety.”

But she shook her head, without saying anything further about it. Then she was very kind to Octave, questioning him with a motherly and sisterly affection as to how he had employed the day. During nearly nine months that he had been boarding with them, she had always treated him thus as a child of the house.

At length the architect appeared.

“Good evening, my pet; good evening, my duck,” said he, kissing her with his doting air of a good husband. “Another fool has been detaining me in the street!”

Octave moved away, and he heard them exchange a few words in a low voice.

“Will she come?”

“No; what is the good? and, above all, do not worry yourself.”

“You declared to me that she would come.”

“Well! yes; she is coming. Are you pleased? It is for your sake that I have done it.”

They took their seats at the table. During the whole of dinnertime they talked of the English language, which little Angèle had been learning for a fortnight past.

They were taking their dessert, when a ring at the bell caused Madame Campardon to start.

“It is madame’s cousin,” Lisa returned and said, in the wounded tone of a servant whom one has omitted to let into a family secret.

And it was indeed Gasparine who entered. She wore a black woolen dress, looking very quiet, with her thin face, and her air of a poor shop-girl. Rose, tenderly enveloped in her dressing-gown of cream-color silk, and plump and fresh, rose up so moved that tears filled her eyes.

“Ah! my dear,” murmured she, “you are good. We will forget everything; will we not?”

She took her in her arms and gave her two hearty kisses. Octave discreetly wished to retire. But they grew angry: he could remain; he was one of the family. So he amused himself by looking on. Campardon, at first greatly embarrassed, turned his eyes away from the two women, puffing about, and looking for a cigar; whilst Lisa, who was roughly clearing the table, exchanged glances with surprised Angèle.

“It is your cousin,” at length said the architect to his daughter. “You have heard us speak of her. Come, kiss her now.”

She kissed her with her sullen air, troubled by the sort of governess glance with which Gasparine took stock of her, after asking some questions respecting her age and education. Then, when the others passed into the drawing-room, she preferred to follow Lisa, who slammed the door, saying, without even fearing that she might be heard:

“Ah, well! it’ll become precious funny here now!”

In the drawing-room, Campardon, still restless, began to excuse himself.

“On my word of honor! the happy idea was not mine. It is Rose who wished to be reconciled. Every morning, for more than a week past, she has been saying to me: ‘Now, go and fetch her.’ So I ended by fetching you.”

And, as though he had felt the necessity of convincing Octave, he took him up to the window.

“Well! women are women. It bothered me, because I have a dread of rows. One on the right, the other on the left, there was no squabbling possible. But I had to give in. Rose says we shall be far happier thus. Anyhow, we will try. It depends on these two, now, to make my life comfortable.”

Meanwhile Rose and Gasparine had seated themselves side by side on the sofa. They were talking of the past, of the days lived at Plassans, with good papa Domergue.

“And your health?” asked she, in a low voice. “Achille spoke to me about it. Is it no better?”

“No, no,” replied Rose, in a melancholy tone. “You see, I eat; I look very well. But it gets no better; it will never get any better.”

As she began to cry, Gasparine, in her turn, took her in her arms and pressed her against her flat and ardent breast, whilst Campardon hastened to console them.

“Why do you cry?” asked she maternally. “The main thing is that you do not suffer. What does it matter if you have always people about you to love you?”

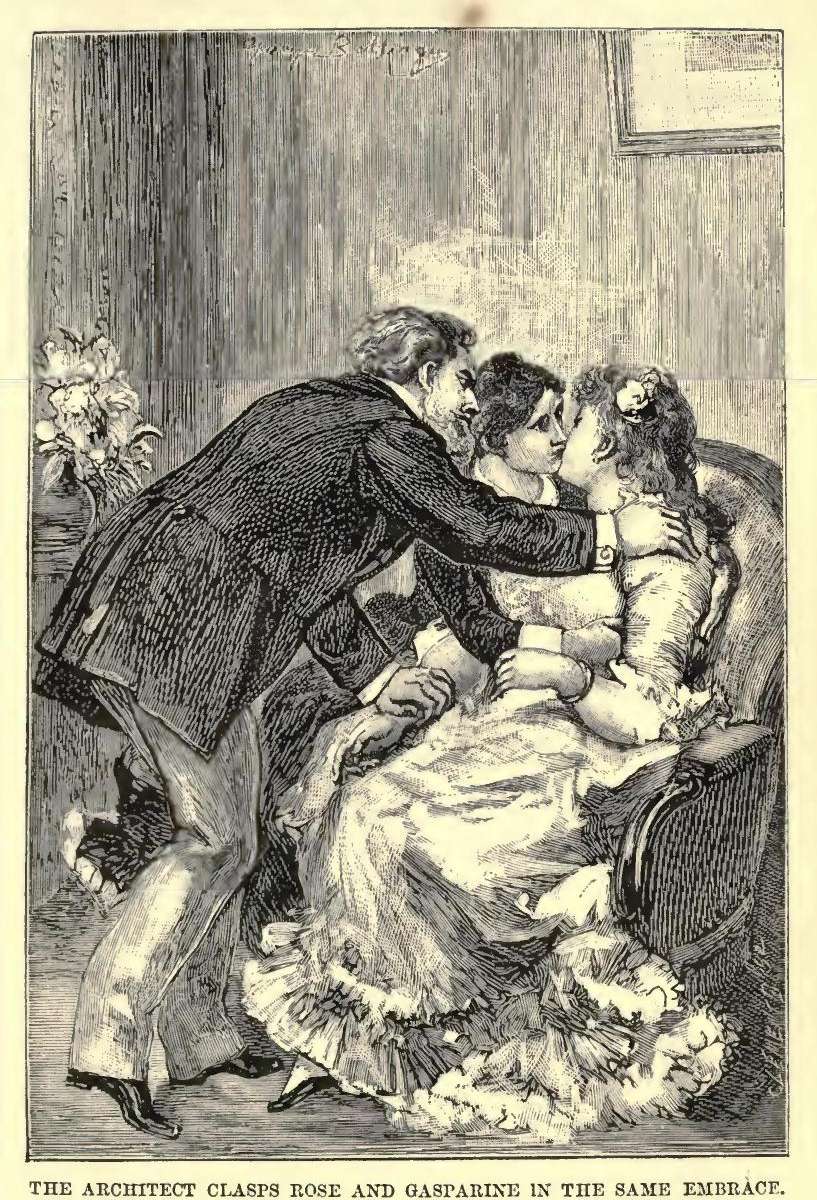

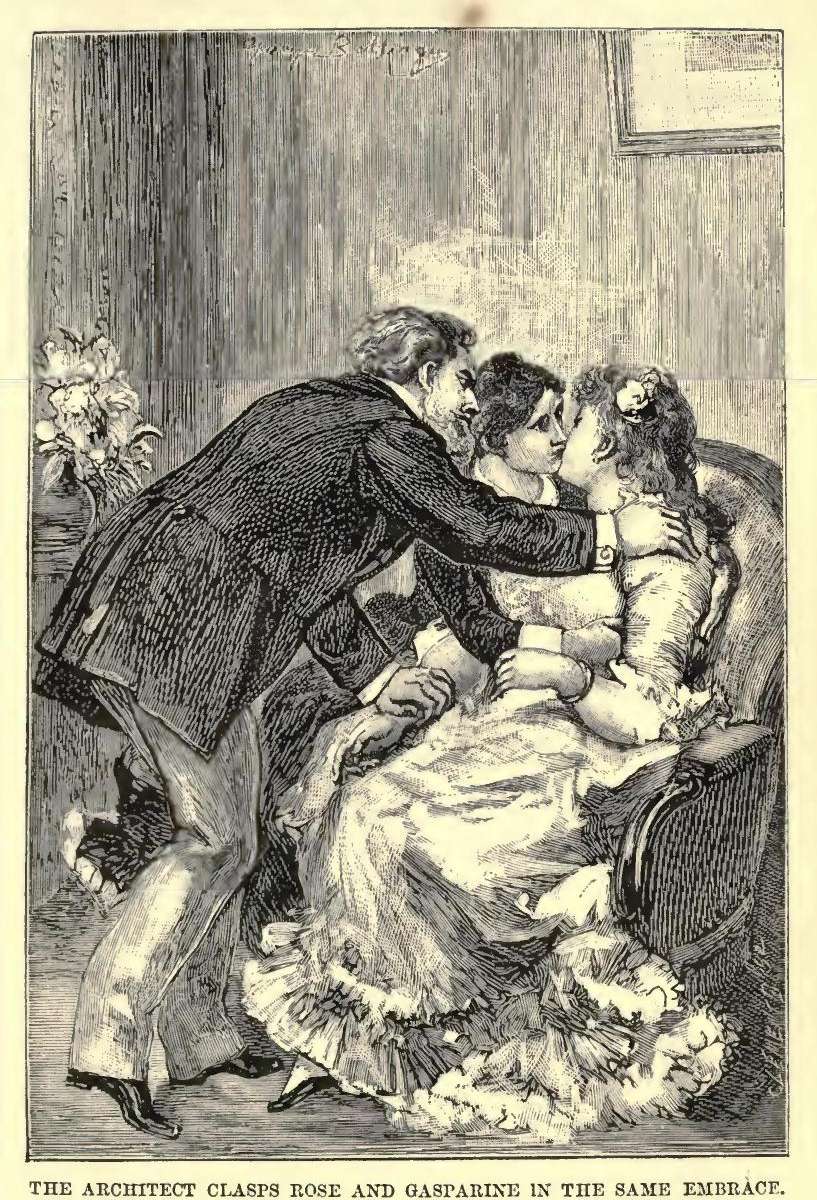

Rose was becoming calmer, and already smiling amidst her tears. Then the architect, carried away by his feelings, clasped them both in the same embrace, kissing them alternately, and stammering:

“Yes, yes, we will love each other very much, we will love you such a deal, my poor little duck. You will see how well everything will go, now that we are united.”

And, turning toward Octave, he added:

“Ah! my dear fellow, people may talk, there is nothing, after all, like family ties!”

The end of the evening was delightful. Campardon, who usually fell asleep on leaving the table if he remained at home, recovered all his artist’s gayety, the old jokes and the broad songs of the School of Fine Arts. When, toward eleven o’clock, Gasparine prepared to leave, Rose insisted on accompanying her to the door, in spite of the difficulty she experienced in walking that day: and, leaning over the balustrade, in the grave silence of the staircase, she called after her:

“Come and see us often!”

On the morrow, Octave, feeling interested, tried to make the cousin talk at “The Ladies’ Paradise,” whilst they were receiving a consignment of linen goods together. But she answered curtly, and he felt that she was hostile, annoyed at his having been a witness the evening before. Moreover, she did not like him; she even displayed a sort of rancor toward him in their business relations.

Octave had given himself six months, and, though scarcely four had passed, he was becoming impatient. Every morning he asked himself whether he should not hurry matters forward, seeing the little progress he had made in the affections of this woman, always so icy and gentle. She had ended, however, by showing a real esteem for him, won over by his enlarged ideas, his dreams of vast modern warehouses discharging millions of merchandise into the streets of Paris. Often, when her husband was not there, and she opened the correspondence with the young man of a morning, she would detain him beside her and consult him, profiting a great deal by his advice, and a sort of commercial intimacy was thus gradually established between them. Their hands met amidst bundles of invoices, their breaths mingled as they added up columns of figures, and they yielded to moments of emotion before the open cash-box after some extra fortunate receipts. He even took advantage of these occasions, his tactics being now to reach her heart through her good trader’s nature, and to conquer her on a day of weakness, in the midst of the great emotion occasioned by some unexpected sale. So he remained on the watch for some surprising occurrence which should deliver her up to him.

About this time, Monsieur Hédouin, having fallen ill, went to pass a season at Vichy to take the waters. Octave, to speak frankly, was delighted. Though as cold as marble, Madame Hédouin would become more tender-hearted during her enforced widowhood. But he fruitlessly awaited a quiver, a languidness of desire. Never had she been so active, her head so free, her eye so clear.

At heart, though, the young man did not despair. At times he thought he had reached the goal, and was already arranging his mode of living for the near day when he would be the lover of his employer’s wife. He had kept up his connection with Marie to help him to wait patiently; only, though she was convenient and cost him nothing, she might perhaps one day become irksome, with her faithfulness of a beaten cur. Therefore, at the same time that he took her in his arms on the nights when he felt dull, he would be thinking of a way of breaking off with her. To do so abruptly seemed to him to be worse than foolish. One holiday morning, when about to rejoin his neighbor’s wife, the neighbor himself having gone out early, the idea had at length come to him of restoring Marie to Jules, of sending them in a loving way into each other’s arms, so that he might withdraw with a clear conscience. It was, moreover, a good action, the touching side of which relieved him of all remorse. He waited a while, however, not wishing to find himself without a female companion of some kind.

At the Campardons’ another complication was occupying Octave’s mind. He felt that the moment was arriving when he would have to take his meals elsewhere. For three weeks past Gasparine had been making herself quite at home there, with an authority daily increasing. At first she had begun by coming every evening; then she had appeared at lunch: and, in spite of her work at the shop, she was commencing to take charge of everything, of Angèle’s education, and of the household affairs. Rose was ever repeating in Campardon’s presence:

“Ah! if Gasparine only lived with us!”

But each time the architect, blushing with conscientious scruples, and tormented with shame, cried out:

“No, no; it cannot be. Besides, where would you put her to sleep?”

And he explained that they would have to give his study as a bedroom to their cousin, whilst he would move his table and plans into the drawing-room. It would certainly not inconvenience him in the least; he would, perhaps, decide to make the alteration one day, for he had no need of a drawing-room, and his study was becoming too cramped for all the work he had in hand. Only, Gasparine might very well remain as she was. What need was there to live all in a heap?

“When one is comfortable,” repeated he to Octave, “it is a mistake to wish to be better.”

About that time he was obliged to go and spend two days at Evreux. He was worried about the work in hand at the bishop’s palace. He had yielded to the bishop’s desires without a credit having been opened for the purpose, and the construction of the range for the new kitchens and of the heating apparatus threatened to amount to a very large figure, which it would be impossible to include in the cost of repairs. Besides that, the pulpit, for which three thousand francs had been granted, would come to ten thousand at least. He wished to talk the matter over with the bishop, so as to take certain precautions.

Rose was only expecting him to return on the Sunday night. He arrived in the middle of lunch, and his sudden entrance caused quite a scare. Gasparine was seated at the table, between Octave and Angèle. They pretended to be all at their ease; but there reigned a certain air of mystery. Lisa had closed the drawing-room door at a despairing gesture from her mistress, whilst the cousin kicked beneath the furniture some pieces of paper that were lying about.

When Campardon talked of changing his things, they stopped him.

“Wait a while. Have a cup of coffee, as you lunched at Evreux.”

At length, as he noticed Rose’s embarrassment, she went and threw her arms around his neck.

“My dear, you must not scold me. If you had not returned till this evening, you would have found everything straight.”

She tremblingly opened the doors, and took him into the drawingroom and the study. A mahogany bedstead, brought that morning by a furniture dealer, occupied the place of the drawing-table, which had been moved into the middle of the adjoining room; but as yet nothing had been put straight; portfolios were knocking about amongst some of Gasparine’s clothes; the Virgin with the Bleeding Heart was lying against the wall, kept in position by a new wash-stand.

“It was a surprise,” murmured Madame Campardon, her heart bursting, as she hid her face in her husband’s waistcoat.

He, deeply moved, looked about him. He said nothing, and avoided encountering Octave’s eyes. Then, Gasparine asked, in her sharp voice:

“Does it annoy you, cousin? It is Rose who pestered me. But, if you think I am in the way, it is not too late for me to leave.”

“Oh! cousin!” at length exclaimed the architect. “All that Rose does is well done.”

And, the latter having burst out sobbing on his breast, he added:

“Come, my duck, how foolish of you to cry! I am very pleased. You wish to have your cousin with you; well! have your cousin with you. Everything suits me. Now, do not cry any more! See! I kiss you like I love you, so much! so much!”

He devoured her with caresses. Then, Rose, who melted into tears for a word, but who smiled at once, in the midst of her sobs, was consoled. She kissed him in her turn, on his beard, saying to him, gently:

“You were harsh. Kiss her also.”

Campardon kissed Gasparine. They called Angèle, who had been looking on from the dining-room, her eyes bright and her mouth wide open; and she had to kiss her also. Octave had moved away, having arrived at the conclusion that they were becoming far too loving in that family. He had noticed with surprise Lisa’s respectful attitude and smiling attentiveness toward Gasparine. She was decidedly an intelligent girl, that hussy with the blue eyelids!

Meanwhile, the architect had taken off his coat, and whistling and singing, as lively as a boy, he spent the afternoon in arranging the cousin’s room. Then Octave understood that his presence interfered with the free expansion of their hearts; he felt he was one too many in such a united family, so mentioned that he was going to dine out that evening. Moreover, he had made up his mind; on the morrow he would thank Madame Campardon for her kind hospitality, and invent some story for no longer trespassing upon it.

Toward five o’clock, as he was regretting that he did not know where to find Trublot, he had the idea to go and ask the Pichons for some dinner, so as not to pass the evening alone. But, on entering their apartments, he found himself in the midst of a deplorable family scene. The Vuillaumes were there, trembling with rage and indignation.

“It is disgraceful, sir!” the mother was saying, standing up with her arm thrust out toward her son-in-law, who was sitting in a chair in a state of collapse. “You gave me your word of honor.”

“And you,” added the father, causing his daughter to draw back trembling as far as the sideboard, “do not try to defend him, you are quite as guilty. Do you wish to die of hunger!”

Madame Vuillaume had put on her bonnet and shawl again.

“Good-bye!” uttered she, in a solemn tone. “We will at least not encourage your dissoluteness by our presence. As you no longer pay the least attention to our wishes, we have nothing to detain us here. Good-bye!”

And, as through force of habit her son-in-law rose to accompany them, she added:

“Do not trouble yourself, we shall be able to find the omnibus very well without you. Pass first, Monsieur Vuillaume. Let them eat their dinner, and much good may it do them, for they won’t always have one!”

Octave, thoroughly bewildered, drew on one side. When they had gone, he looked at Jules, who was still in a state of collapse on his chair, and at Marie leaning against the sideboard and looking very pale. Neither of them said a word.

“What is the matter?” asked he.

But, without answering him, the young woman commenced scolding her husband in a doleful voice.

“I told you how it would be. You should have waited, and let them learn the thing by degrees. There was no hurry, it does not show as yet.”

“What is the matter?” repeated Octave.

Then, without even turning her head, she said bluntly, in the midst of her emotion!

“I am in the family way.”

“I have had enough of them!” cried Jules, rising indignantly. “I thought it right to tell them at once of this bother. I wonder if they think it amuses me! I am more taken in by it all than they are. More especially, by Jove! as it is through no fault of mine. Is it not true, Marie, that we have no idea how it has come about?”

“That is so, indeed,” affirmed the young woman.

It quite affected Octave; and he felt a violent desire to do something nice for the Pichons. Jules continued to grumble: they would receive the child all the same, only it would have done better to have remained where it was. On her side, Marie, generally so gentle, became angry, and ended by agreeing with her mother, who never forgave disobedience. And the couple were coming to a quarrel, throwing the youngster from one to the other, accusing each other of being the cause of it, when Octave gayly interfered.

“It is no use quarreling, now that it is there. Come, we won’t dine here; it would be too sad. I will take you to a restaurant, if you are agreeable.”

The young woman blushed. Dining at a restaurant was her delight. She spoke, however, of her little girl, who invariably prevented her from having any pleasure. But it was decided that, for this once, Lilitte should go too. And they spent a very pleasant evening. Octave took them to the “Bœuf à la Mode,” where they had a private room, to be more at their ease, as he said. There, he overwhelmed them with food, with an earnest prodigality, without thinking of the bill, happy at seeing them eat. He even, at dessert, when they had laid Lilitte down between two of the sofa cushions, called for champagne; and they sat there, their elbows on the table, their eyes dim, all three full of heart, and feeling languid from the suffocating heat of the room. At length, at eleven o’clock, they talked of going home; but they were red, and the fresh air of the street intoxicated them. Then, as the child, heavy with sleep, refused to walk, Octave, to do things handsomely until the end, insisted on hailing a cab, though the Rue de Choiseul was close by. In the cab, he was scrupulous to the point of not pressing Marie’s knees. Only, upstairs, whilst Jules was tucking Lilitte in, he imprinted a kiss on the young woman’s forehead, the farewell kiss of a father parting with his daughter to a son-in-law. Then, seeing them very loving and looking at each other in a drunken sort of way, he left them to themselves, wishing them a good-night and many pleasant dreams as he closed the door.

“Well!” thought he, as he jumped all alone into bed, “it has cost me fifty francs, but I owed them quite that. After all, my only wish is that her husband may make her happy, poor little woman!”

And, with his heart full of emotion, he resolved, before falling asleep, to make his grand attempt on the following evening.

Every Monday, after dinner, Octave assisted Madame Hédouin to examine the orders of the week. For this purpose they both withdrew to the little closet at the back, a narrow apartment which merely contained a safe, a desk, two chairs and a sofa. But it so happened that on the Monday in question the Duveyriers were going to take Madame Hédouin to the Opéra-Comique. So, toward three o’clock, she sent for the young man. In spite of the bright sunshine, they were obliged to burn the gas, for the closet only received a pale light from an inner courtyard. He bolted the door, and, as she looked at him in surprise, he murmured:

“No one can come and disturb us.”

She nodded her head approvingly, and they set to work. The new summer goods were going splendidly, the business of the house continued increasing. That week especially the sale of the little woolens seemed so promising that she heaved a sigh.

“Ah! if we only had enough room!”

“But,” said he, commencing the attack, “it depends upon yourself. I have had an idea for some time past, which I wish to lay before you.”

It was the stroke of audacity he had been waiting for. His idea was to purchase the adjoining house in the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, to give notice to an umbrella-dealer and to a toy-merchant, and then to enlarge the warehouses, to which they could add several other vast departments. And he warmed up as he spoke, showing himself full of disdain for the old way of doing business in the depths of damp, dark shops, without any display, evoking a new commerce with a gesture, piling up in palaces of crystal all the luxury pertaining to woman, turning over millions in the light of day, and illuminating at night-time in a princely style.

“You will crush the other drapers of the Saint-Roch neighborhood,” said he; “you will secure all the small customers.”

Madame Hédouin listened to him, her elbow on a ledger, her beautiful, grave head buried in her hand. She was born at “The Ladies’ Paradise,” which had been founded by her father and her uncle. She loved the house; she could see it expanding, swallowing up the neighboring houses, and displaying a royal frontage, and this dream suited her active intelligence, her upright will, her woman’s delicate intuition of the new Paris.

“Uncle Deleuze would never give his consent,” murmured she. “Besides, my husband is too unwell.”

Then, seeing her wavering, Octave assumed his most seductive voice—an actor’s voice, soft and musical. At the same time he looked tenderly at her, with his eyes the color of old gold, which some women thought irresistible. But, though the gas-jet flared close to the nape of her neck, she remained as cool as ever; she merely fell into a revery, half stunned by the young man’s inexhaustible flow of words. He had come to studying the affair from the money point of view, already making an estimate with the impassioned air of a romantic page declaring a long pent up love. When she suddenly awoke from her reflections, she found herself in his arms. He was thinking that she was at length yielding.

“Dear me! so this is what it all meant!” said she in a sad tone of voice, freeing herself from him as from some tiresome child.

“Well! yes, I love you,” cried he. “Oh! do not repel me. With you I will do great things——”

And he went on thus to the end of the tirade, which had a false ring about it. She did not interrupt him; she was standing up and again scanning the pages of the ledger. Then, when he had finished, she replied:

“I know all that—I have already heard it before. But I thought you were more sensible than the others, Monsieur Octave. You grieve me, really you do, for I had counted upon you. However, all young men are foolish. We need a great deal of order in such a house as this, and you begin by desiring things which would disturb us from morning to night. I am not a woman here, I have too much to occupy me. Come, you who are so well organized, how is it you did not comprehend that it could never be, because in the first place it is stupid, in the second useless, and, moreover, luckily for me, I do not care the least about it!”

He would have preferred her to have been indignantly angry, displaying grand sentiments. Her calm tone of voice, her quiet reasoning of a practical woman, sure of herself, disconcerted him. He felt himself becoming ridiculous.

“Have pity, madame,” stammered he, before losing all hope. “See how I suffer.”

“No, you do not suffer. Anyhow, you will get over it. Hark! there is some one knocking, you would do better to open the door.”

Then he had to draw the bolt. It was Mademoiselle Gasparine, who wished to know if any lace-trimmed chemises were expected. The bolted door had surprised her. But she knew Madame Hédouin too well; and, when she saw her with her cold air standing in front of Octave, who was full of uneasiness, a slight mocking smile played about her lips as she looked at him. It exasperated him, and in his own mind he accused her of having been the cause of his ill-success.

“Madame,” declared he, abruptly, when Gasparine had withdrawn, “I leave your employment this evening.”

This was a surprise for Madame Hédouin. She looked at him.

“Why so? I do not discharge you. Oh! it will not make any difference; I have no fear.”

These words decided him. He would leave at once; he would not endure his martyrdom a minute longer.

“Very good, Monsieur Octave,” resumed she as serenely as ever. “I will settle with you directly. However, the firm will regret you, for you were a good assistant.”

Once out in the street, Octave perceived that he had behaved like a fool. Four o’clock was striking, the gay spring sun covered with a sheet of gold a whole corner of the Place Gaillon. And, angry with himself, he wandered at hap-hazard down the Rue Saint-Roch, discussing the way in which he ought to have acted. He would go and see if Campardon happened to be in the church, and take him to the café to have a glass of Madeira. It would help to divert his thoughts. He entered by the vestibule into which the vestry door opened, a dark, dirty passage such as is to be met with in houses of ill-repute.

“You are perhaps looking for Monsieur Campardon?” said a voice close beside him, as he stood hesitating, scrutinizing the nave with his glance.

It was the Abbé Mauduit, who had just recognized him. The architect being away, he insisted on showing the works, about which he was most enthusiastic, to the young man.

“Walk in,” said the Abbé Mauduit, gathering up his cassock. “I will explain everything to you.”

“Here we are,” continued the priest. “I had the idea of lighting the central group of the Calvary from above by means of an opening in the cupola. You can fancy what an effect it will have.”

“Yes, yes,” murmured. Octave, whose thoughts were diverted by this stroll amidst building materials.

The Abbé Mauduit, speaking in a loud voice, had the air of a stage-carpenter directing the placing of some gorgeous scenery.

And he turned round to call out to a workman:

“Move the Virgin on one side; you will be breaking her leg directly.”

The workman called a comrade. Between them they got hold of the Virgin round the small of her back, and carried her to a place of safety, like some tall white girl who had fallen down under a nervous attack.

“Be careful!” repeated the priest, following them through the rubbish, “her dress is already cracked. Wait a while!”

He gave them a hand, seizing Mary round the waist, and then, all covered with plaster, withdrew from the embrace.

“Then,” resumed he, returning to Octave, “just imagine that the two bays of the nave there before us are open, and go and stand in the chapel of the Virgin. Over the altar, and through the chapel of Perpetual Adoration, you will behold the Calvary right at the back. Just fancy the effect: these three enormous figures, this bare and simple drama in this tabernacle recess, beyond the dim, mysterious light of the stained-glass windows, the lamps and the gold candelabra. Eh? I think it will be irresistible!”

He was waxing eloquent, and, proud of his idea, he laughed joyfully.

“The most skeptical will be moved,” observed Octave, to please him.

“That is what I think!” cried he. “I am impatient to see everything in place.”

“I am going to see Monsieur Campardon this evening,” at length said the Abbe Mauduit. “Ask him to wait in for me. I wish to speak to him about an improvement without being disturbed.”

And he bowed with his worldly air. Octave was calmed now. Saint-Roch, with its cool vaults, had unbraced his nerves. He looked curiously at this entrance to a church through a private house, at the doorkeeper’s room, from whence at night time the door was often opened for the cause of the faith, at all that corner of a convent lost amidst the black conglomeration of the neighborhood. Out in the street, he again raised his eyes; the house displayed its bare frontage, with its barred and curtainless windows; but boxes of flowers were fixed by iron supports to the windows of the fourth floor; and, down below, in the thick walls, were narrow shops, which helped to fill the coffers of the clergy—a cobbler’s, a clock-maker’s, an embroiderer’s, and even a wine shop, where the mutes congregated whenever there was a funeral. Octave, who, from his rebuff, was in a mood to renounce the world, regretted the quiet lives which the priests’ servants led up there in those rooms enlivened with verbenas and sweet peas.

That evening, at half past six, as he entered the Campardons’ apartments without ringing, he came suddenly upon the architect and Gasparine kissing each other in the ante-room. The latter, who had just come from the warehouse, had not even given herself time to close the door. Both stood stock-still.

“My wife is combing her hair,” stammered the architect, for the sake of saying something. “Go in and see her.”

Octave, feeling as embarrassed as themselves, hastened to knock at the door of Rose’s room, where he usually entered like a relation. He really could no longer continue to board there, now that he caught them behind the doors.

“Come in!” cried Rose’s voice. “So it is you, Octave. Oh! there is no harm.”

She had not, however, donned her dressing-gown, and her arms and shoulders, as white and delicate as milk, were bare. Sitting attentively before the looking-glass, she was rolling her golden hair in little curls.

“So you are making yourself beautiful again to-night,” said Octave, smiling.

“Yes, for it is the only amusement I have,” replied she. “It occupies me. You know I have never been a good housewife; and, now that Gasparine will be here—Eh? d