CHAPTER X.

THEN, Octave found himself brought into closer contact with the Duveyriers. Often, when Madame Duveyrier returned from a walk, she would come through her brother’s shop, and stop to talk a minute with Berthe; and, the first time that she saw the young man behind one of the counters, she amiably reproached him for not keeping his word, reminding him of his long-standing promise to come and see her one evening, and try his voice at the piano. She wished to give a second performance of the “Benediction of the Daggers,” at one of her first Saturdays at home of the coming winter, but with two extra tenors, something very complete.

“If it does not interfere with your arrangements,” said Berthe one day to Octave, “you might go up to my sister-in-law’s after dinner. She is expecting you.”

She maintained toward him the attitude of a mistress, simply polite.

“The fact is,” he observed, “I intended arranging these shelves this evening.”

“Do not trouble about them,” resumed she, “there are plenty of people here to do that. I give you your evening.”

Toward nine o’clock, Octave found Madame Duveyrier awaiting him in her grand white and gold drawing-room. Everything was ready, the piano open, the candles lit. A lamp placed on a small round table beside the instrument only imperfectly lighted the room, one half of which remained in shadow. Seeing the young woman alone, he thought it proper to ask after Monsieur Duveyrier. She replied that he was very well; his colleagues had selected him to report on a very grave affair, and he had just gone out to obtain certain information respecting it.

“You know; the affair of the Rue de Provence,” said she simply.

“Ah! he has that in hand!” exclaimed Octave.

It was a scandal which was the talk of all Paris, quite a clandestine prostitution, young girls of fourteen procured for high personages. Clotilde added:

“Yes, it gives him a great deal of work. For a fortnight past all of his evenings have been taken up with it.”

“No doubt! for he too has the cure of souls,” murmured he, embarrassed by her clear glance.

“Well! sir, shall we begin?” resumed she. “You will excuse my importunity, will you not? And open your lungs, display all your powers, as Monsieur Duveyrier is not here. You, perhaps, heard him boast that he did not like music.”

She put such contempt into the words, that he thought it right to risk a faint laugh. Moreover, it was the sole bitter feeling which at times escaped her before other people with respect to her husband, when exasperated by his jokes on her piano, she who was strong enough to hide the hatred and the physical repulsion with which he inspired her.

“How can one help liking music?” remarked Octave with an air of ecstasy, so as to make himself agreeable.

Then she seated herself on the music-stool. A collection of old tunes was open on the piano. She had already selected an air out of “Zémire and Azor,” by Grétry. As the young man could only just manage to read his notes, she made him go through it first in a low voice. Then she played the prelude, and he sang the first verse.

“Perfect!” cried she with delight, “a tenor, there is not the least doubt of it, a tenor! Pray continue, sir.”

Octave, feeling highly flattered, gave out the two other verses. She was beaming. For three years past she had been seeking for one! And she told him of all her vexations, Monsieur Trublot, for instance; for it was a fact, the causes of which were worth studying, that there were no longer any tenors among the young men of society: no doubt it was owing to tobacco.

“Be careful, now!” resumed she, “we must put some expression into it. Begin it boldly.”

Her cold face assumed a languid expression, her eyes turned toward him with an expiring air. Thinking that she was warming, he became more animated also, and considered her charming.

“You will get along very well,” said she. “Only, accentuate the time more. See, like this.”

And she herself sang, repeating quite twenty times: “More trembling than you,” bringing out the notes with the rigor of a sinless woman, whose passion for music was not more than skin deep in her mechanism. Her voice rose little by little, filling the room with shrill cries, when they both suddenly heard some one exclaiming loudly behind their backs:

“Madame! madame!”

She started, and, recognizing her maid Clémence, exclaimed:

“Eh? what?”

“Madame, your father has fallen with his face in his papers, and he doesn’t move. We are so frightened.”

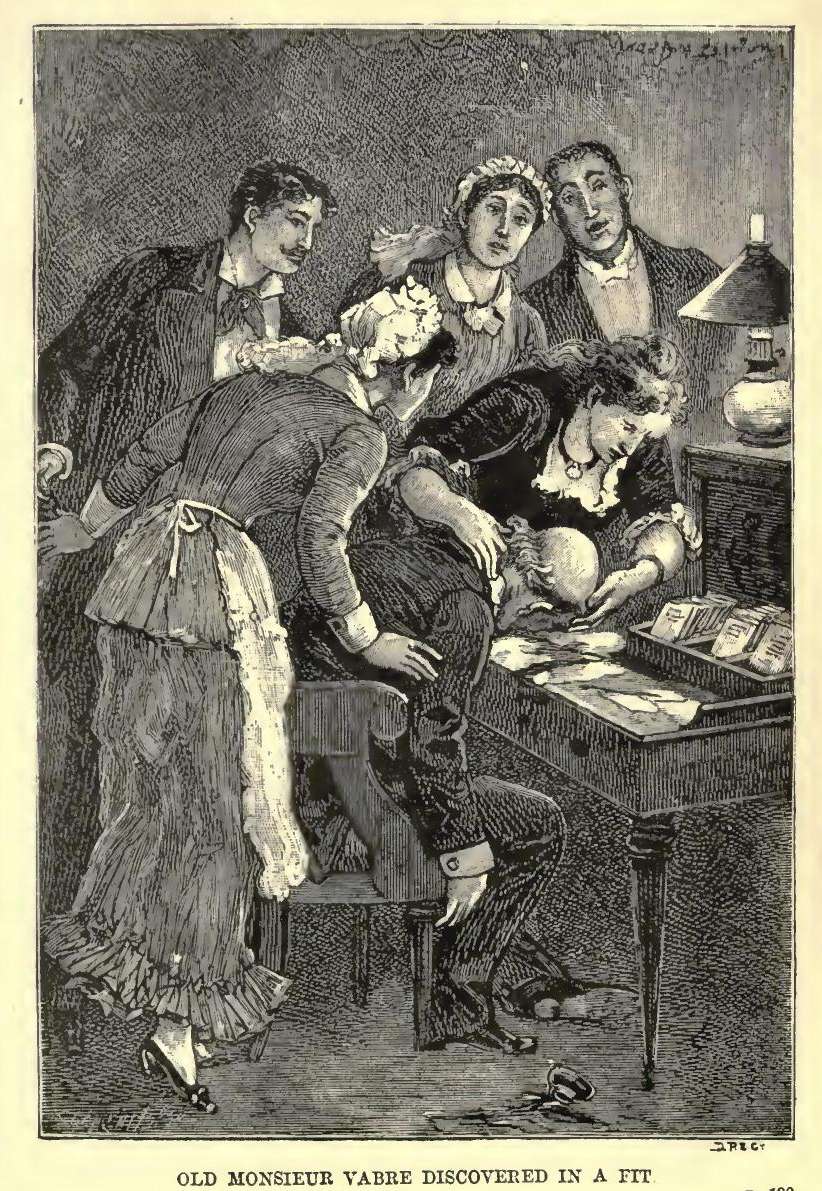

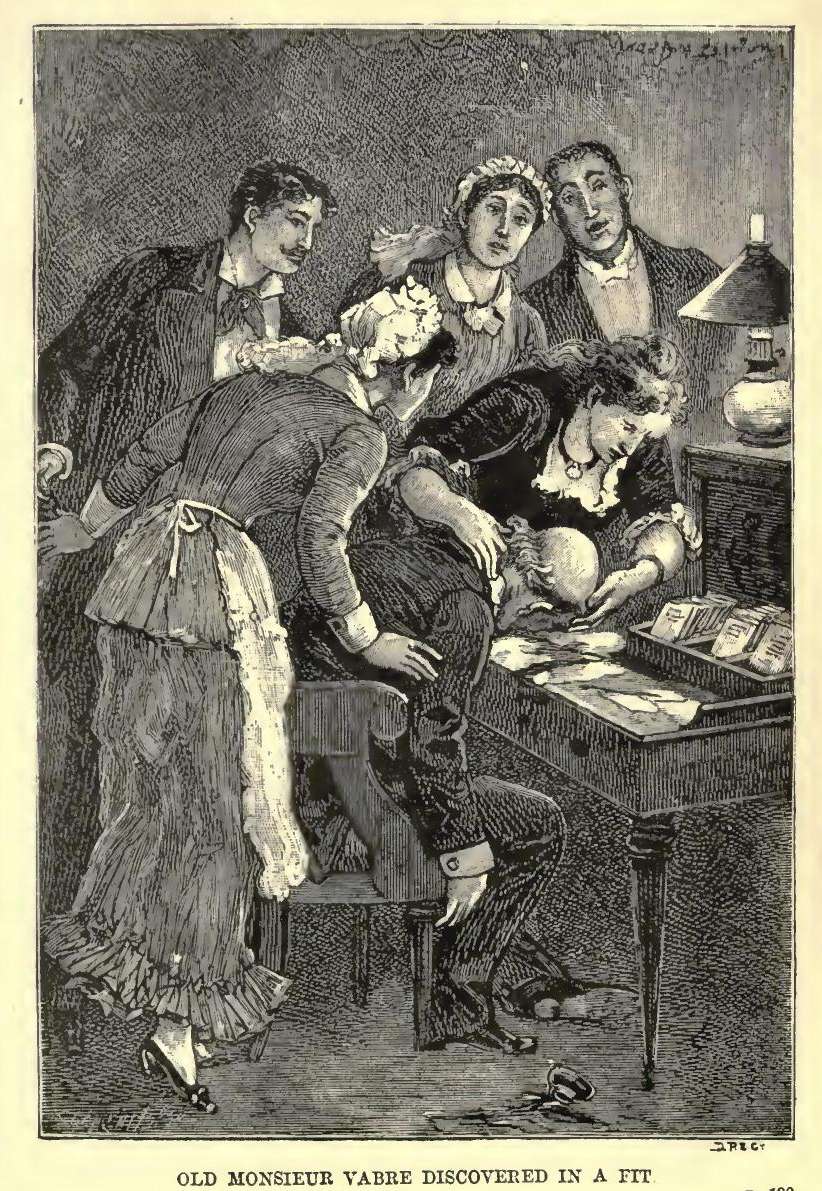

Then, without exactly understanding, and greatly surprised, she quitted the piano and followed Clémence. Octave, who was uncertain whether to accompany her, remained walking about the drawing-room. However, after a few minutes of hesitation and embarrassment, as he heard people rushing about and calling out distractedly, he made up his mind, and, crossing a room that was in darkness, he found himself in Monsieur Vabre’s bedchamber.

“He is in a fit,” said Octave. “He must not be left there. We must get him onto his bed.”

But Madame Duveyrier was losing her head. Emotion was little by little seizing upon her cold nature. She kept repeating:

“Do you think so? do you think so? O good heavens! O my poor father!”

Hippolyte, a prey to an uneasy feeling, to a visible repugnance to touch the old man, who might go off in his arms, did not hurry himself. Octave had to call to him to help. Between them they laid him on the bed.

“Bring some warm water!” resumed the young man, addressing Julie. “Wipe his face.”

Now, Clotilde became angry with her husband. Ought he to have been away? What would become of her if anything happened?

“To leave me alone like this!” continued Clotilde. “I don’t know, but there must be all sorts of affairs to settle. O my poor father!”

“Would you like me to inform the other members of the family?” asked Octave. “I can fetch your brothers. It would be prudent.” She did not answer. Two big tears swelled her eyes, whilst Julie and Clémence tried to undress the old man.

“Madame,” observed Clémence, “one side of him is already quite cold.”

This increased Madame Duveyrier’s anger. She no longer spoke, for fear of saying too much before the servants. Her husband did not, apparently, care a button for their interests! Had she only been acquainted with the law! And she could not remain still; she kept walking up and down before the bed. Octave, whose attention was diverted by the sight of the tickets, looked at the formidable apparatus which covered the table; it was a big oak box, filled with a series of cardboard tickets, scrupulously sorted, the stupid work of a lifetime. Just as he was reading on one of these tickets: “‘Isidore Charbotel;’ ‘Exhibition of 1857,’ ‘Atalanta;’ ‘Exhibition of 1859,’ ‘The Lion of Androcles;’ ‘Exhibition of 1861,’ ‘Portrait of Monsieur P——-,’” Clotilde went and stood before him and said resolutely, in a low voice:

“Go and fetch him.”

And, as he evinced his surprise, she seemed, with a shrug of her shoulders, to cast off the story about the report of the affair of the Rue de Provence, one of those eternal pretexts which she invented for her acquaintances. She let out everything in her emotion.

“You know, Rue de la Cerisaie. All our friends know it.”

He wished to protest.

“I assure you, madame———-”

“Do not stand up for him!” resumed she. “I am only too pleased; he can stay there. Ah! good heavens! if it were not for my poor father!”

Octave bowed. Julie was wiping Monsieur Vabre’s eye with the corner of a towel; but the ink had dried, and the smudge remained in the skin, which was marked with livid streaks. Madame Duveyrier told her not to rub so hard; then she returned to the young man, who was already at the door.

“Not a word to any one,” murmured she. “It is needless to upset the house. Take a cab, call there, and bring him back in spite of everything.”

When he had gone, she sank onto a chair beside the patient’s pillow. He had not recovered consciousness; his breathing alone, a deep and painful breathing, troubled the mournful silence of the chamber. Then, the doctor not arriving, finding herself alone with the two servants, who stood by with frightened looks, she burst out into a terrible fit of sobbing, in a paroxysm of deep grief.

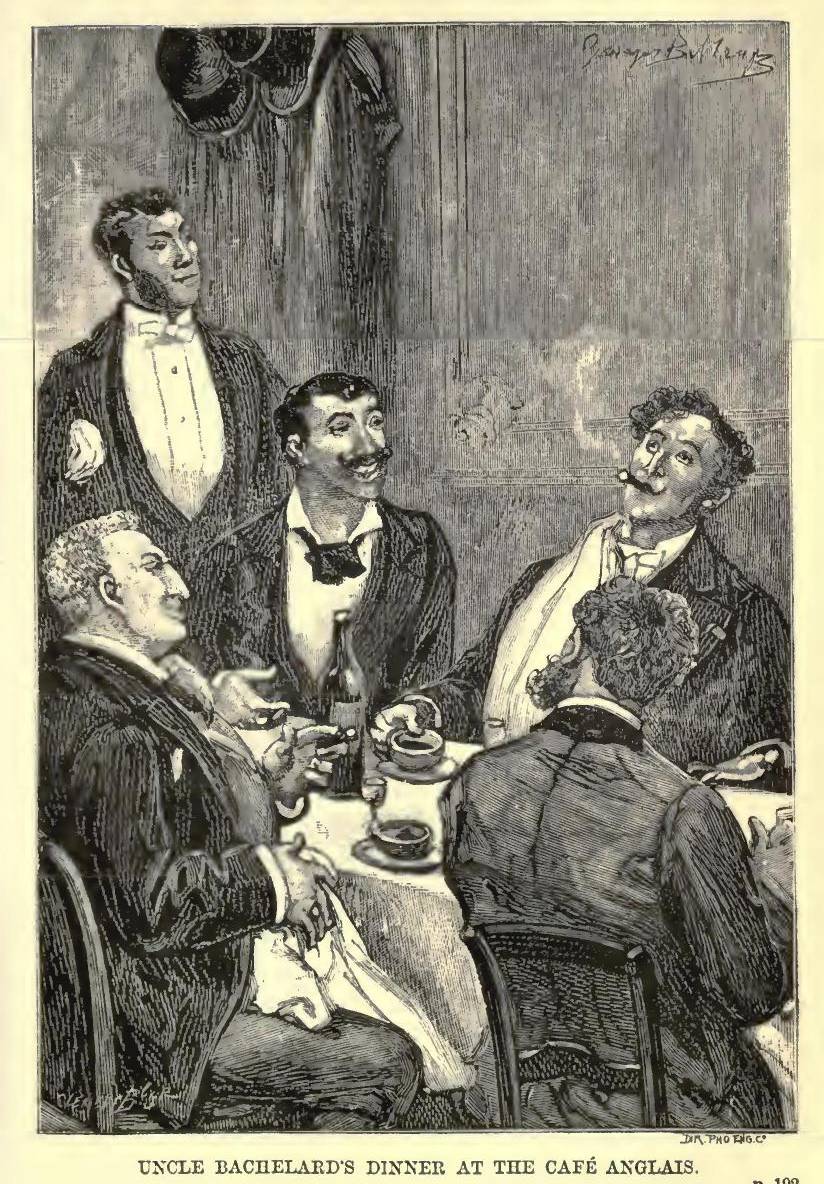

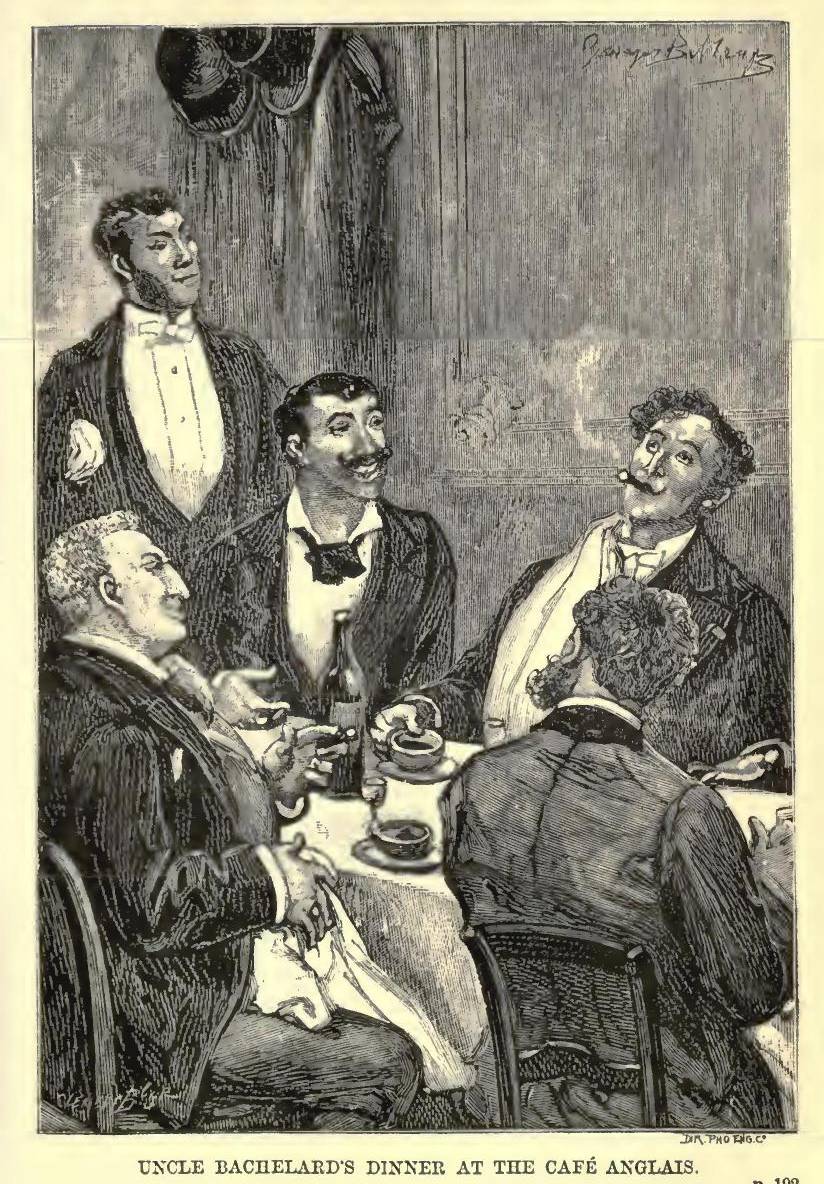

It was at the Café Anglais that uncle Bachelard had invited Duveyrier to dine, without any one knowing why, perhaps for the pleasure of treating a counselor, and of showing him that tradespeople knew how to spend their money. He had also invited Trublot and Gueulin—four men and no women—for women do not know how to eat; they interfere with the truffles, and spoil digestion.

“Drink away! drink away, sir!” he kept saying to Duveyrier; “when wines are good they never intoxicate. It’s the same with food; it never does one harm so long as it’s delicate.”

He, however, was careful. On this occasion he was posing for the gentleman, shaved and brushed up, and with a rose in his buttonhole, restraining himself from breaking the crockery, which he was in the habit of doing. Trublot and Gueulin eat of everything. The uncle’s theory seemed the right one, for Duveyrier, who suffered a great deal from his stomach, had drank considerably, and had returned to the crayfish salad, without feeling the least indisposed, the red blotches on his face merely assuming a purple hue.

Then, when the coffee had been served, with some liquors and cigars, and all the attendants had withdrawn, uncle Bachelard suddenly leaned back in his chair and heaved a sigh of satisfaction.

“Ah!” declared he, “one is comfortable.”

Trublot and Gueulin, also leaning back in their chairs, opened their arms.

“Completely!” said the one.

“Up to the eyes!” added the other.

Duveyrier, who was puffing, nodded his head, and murmured:

“Oh! the crayfish!”

All four looked at each other and chuckled. Their skins were well-nigh bursting, and they were digesting in the slow and selfish way of four worthy citizens who had just had a tuckout away from the worries of their families. It had cost a great deal; no one had partaken of it with them; there was no girl there to take advantage of their emotion; and they unbuttoned their waistcoats, and laid their stomachs as it were on the table. With eyes half-closed, they even avoided speaking at first, each one absorbed in his solitary pleasure. Then, free and easy, and whilst congratulating themselves that there were no women present, they placed their elbows on the table, and, with their excited faces close together, they did nothing but talk incessantly of them.

“As for myself, I am disabused,” declared uncle Bachelard. “It is after all far preferable to be virtuous.”

This conversation tickled Duveyrier’s fancy. He was sipping kummel, whilst sharp twinges of sensuality kept shooting across his stiff, magisterial face.

“For my part,” said he, “I cannot bear vice. It shocks me. Now, to be able to love a woman, one must esteem her, is it not so? Love could not have a nobler mission. In short, a virtuous mistress, you understand me? Then, I do not deny I might succumb.”

“Virtuous mistresses! but I have had no end of them!” cried Bachelard. “They are a far greater nuisance than the others; and such sluts too! Wenches who, behind your back, lead a life fit to give you every possible ailment! Take, for instance, my last, a very respectable-looking little lady, whom I met at a church door. I set her up in business at Les Ternes as a milliner, just to give her a position. She never had a single customer, though. Well, sir, believe me or not as you like, but she had the whole street to sleep with her.”

Gueulin was chuckling, whilst his carroty hair bristled more than usual, and his forehead was bathed in perspiration from the heat of the candles. He murmured, as he sucked his cigar:

“And the other, the tall one at Passy, who had a sweet-stuff shop. And the other, she who had a room over there, with her outfits for orphan children. And the other, the captain’s widow, you surely remember her! she used to show the mark of a sword-thrust on her body. All, uncle, all of them played the fool with you! Now, I may tell you, may I not? Well! I had to defend myself one night against the one with the sword-thrust. She wanted to, but I was not such a fool! One never knows what such women may lead a man to!”

Bachelard seemed annoyed. He recovered his good humor, however, and, blinking his heavy eyelids, said:

“My little fellow, you can have them all; I have something far better.”

And he refused to explain himself further, delighted at having awakened the others’ curiosity. Yet he was burning to be indiscreet, to let them imagine what a treasure he possessed.

“A young girl,” said he at length, “and a genuine one, on my word of honor.”

“Impossible!” cried Trublot, “Such things no longer exist.”

“Of good family!” asked Duveyrier.

“Of most excellent family,” affirmed the uncle. “Imagine something stupidly chaste. A mere chance. She submitted quite innocently. She has no idea of anything even now.”

Gueulin listened to him in surprise; then, making a skeptical gesture, murmured:

“Ah! yes, I know.”

“What? you know!” said Bachelard angrily. “You know nothing at all, my little fellow; no one knows anything. She is for yours truly. She is neither to be seen nor touched. Hands off!” And, turning to Duveyrier, he added:

“You will understand, sir, you who have feeling. It affects me so much going there, that when I come away I feel quite young again. In short, it is a cozy little nook for me, where I can recruit myself after all those hussies. And, if you only knew, she is so polite and so fresh, with a skin like a flower, and a figure not in the least thin, sir, but as round and firm as a peach!”

The counselor’s red blotches were almost bleeding through the rush of blood to his face. Trublot and Gueulin looked at the uncle; and they felt a desire to slap him as they beheld him with his set of false teeth, which were too white, and at the corners of which the saliva trickled.

Bachelard became quite tender-hearted, and resumed, licking the brim of his liquor glass with the tip of his tongue:

“After all, my sole dream is to make the child happy! But there, my pot-belly tells me I am getting old; I’m like a father to her. I give you my word! if I found a very good young fellow, I’d give her to him, oh! in marriage, not otherwise.”

“You would make two happy ones,” murmured Duveyrier sentimentally.

It was almost stifling in the small apartment. A glass of chartreuse that had been upset had made the tablecloth all sticky, and it was also covered with cigar-ash. The gentlemen were in want of some fresh air.

“Would you like to see her?” abruptly asked the uncle, rising from his seat.

They consulted one another with a glance. Well, yes, they were willing, if it could afford him any pleasure; and their affected indifference hid a gluttonous satisfaction at the thought of going and finishing their dessert with the old fellow’s little one.

“Let’s get along, uncle! Which is the way?”

Bachelard became quite grave again, tortured by his ridiculously vain longing to exhibit Fifi, and by his terror of being robbed of her. For a moment he looked to the left, then to the right, in an anxious way. At length he boldly said:

“Well! no, I won’t.”

And he obstinately adhered to his determination, without caring a straw for Trublot’s chaff, nor even deigning to explain by some pretext his sudden change of mind. They therefore had to turn their steps in Clarisse’s direction. As it was a splendid evening, they decided to walk all the way, with the hygienic idea of hastening their digestion. Then they started off down the Rue de Richelieu, pretty steady on their legs, but so full that they considered the pavements far too narrow.

The house in the Rue de la Cerisaie seemed asleep amidst the solitude and the silence of the street. Duveyrier was surprised at not seeing any lights in the third-floor windows. Trublot said, with a serious air, that Clarisse had no doubt gone to bed to wait for them; or perhaps, Gueulin added, she was playing a game of bézique in the kitchen with her maid. They knocked. The gas on the staircase was burning with the straight and immovable flame of a lamp in some chapel. Not a sound, not a breath. But, as the four men passed before the room of the doorkeeper, the latter hastily came out.

“Sir, sir, the key!”

Duveyrier stood stock-still on the first step.

“Is madame not there, then?” asked he.

“No, sir. And, wait a moment, you must take a candle with you.”

As he handed him the candlestick, the doorkeeper allowed quite a chuckle of ferocious and vulgar jocosity to pierce through the exaggerated respect depicted on his pallid countenance. Neither of the two young men nor the uncle had said a word. It was in the midst of this silence, and with bent backs, that they ascended the stairs in single file, the interminable noise of their footsteps resounding up each mournful flight. At their head, Duveyrier, who was puzzling himself trying to understand, lifted his feet with the mechanical movement of a somnambulist; and the candle, which he held with a trembling hand, cast their four shadows on the wall, resembling in their strange ascent a procession of broken puppets.

On the third floor, a faintness came over him, and he was quite unable to find the key-hole. Trublot did him the service of opening the door. The key turned in the lock with a sonorous and reverberating noise, as though beneath the vaulted roof of some cathedral.

“Jupiter!” murmured he, “it doesn’t seem as if the place was inhabited.”

“It sounds empty,” said Bachelard.

“A little family vault,” added Gueulin.

They entered. Duveyrier passed first, holding high the candle. The ante-room was empty, even the hat-pegs had disappeared. The drawing-room and the parlor were also empty: not a stick of furniture, not a curtain at the windows, not even a brass rod. Duveyrier stood as one petrified, first looking down at his feet, then raising his eyes to the ceiling, and then searchingly gazing at the walls, as though he had been seeking the hole through which everything had disappeared.

“What a clear out!” Trublot could not help exclaiming.

“Perhaps the place is going to be done up,” observed Gueulin, without as much as a smile. “Let us see the bed-room. The furniture may have been moved in there.”

But the bed-room was also bare, with that ugly and chilly bareness of plaster walls from which the paper has been torn off. Where the bedstead had stood, the iron supports of the canopy, also removed, left gaping holes; and, one of the windows having been left partly open, the air from the street filled the apartment with the humidity and the unsavoriness of a public square.

“My God! my God!” stuttered Duveyrier, at length able to weep, unnerved by the sight of the place where the friction of the mattresses had rubbed the paper off the wall.

Uncle Bachelard became quite paternal.

“Courage, sir!” he kept repeating. “The same thing happened to me, and I did not die of it. Honor is safe, damn it all!”

The counselor shook his head, and went into the dressing-room, and then into the kitchen. The evidence of the disaster increased. The piece of American cloth behind the washstand in the dressing-room had been taken down, and the hooks had been removed from the kitchen.

“No, that is too much, it is pure capriciousness!” said Gueulin, in amazement. “She might have left the hooks.”

“I can’t stand this any longer, you know,” Trublot ended by declaring, as they visited the drawing-room for the third time.

“Really! I would give ten sous for a chair.”

All four came to a halt, standing.

“When did you see her last?” asked Bachelard.

“Yesterday, sir!” exclaimed Duveyrier.

Gueulin wagged his head. By Jove! it had not taken long, it had been neatly done. But Trublot uttered an exclamation. He had just caught sight of a dirty collar and a damaged cigar on the mantelpiece.

“Do not complain,” said he, laughing, “she has left you a keepsake. It is always something.”

Duveyrier looked at the collar with sudden emotion. Then he murmured:

“Twenty-five thousand francs’ worth of furniture, there was twenty-five thousand francs’ worth! Well! no, no, it is not that which I regret!”

“You will not have the cigar?” interrupted Trublot. “Then, allow me to. It has a hole in it, but I can stick a cigarette paper over that.”

He lighted it at the candle which the counselor was still holding, and, letting himself drop down against the wall, he added:

“So much the worse! I must sit down a while on the floor. My legs will not bear me any longer.”

“I beg of you,” at length said Duveyrier, “to explain to me where she can possibly be.”

Bachelard and Gueulin looked at each other. It was a delicate matter. However, the uncle came to a manly decision, and he told the poor fellow everything, all Clarisse’s goings-on, her continual escapades, the lovers she picked up behind his back, at each of their parties. She had no doubt gone off with the last one, big Payan, that mason of whom a Southern town wished to make an artist. Duveyrier listened to the abominable story with an expression of horror. He allowed this cry of despair to escape him:

“There is, then, no honesty left on earth!”

And suddenly opening his heart, he told them all he had done for her.

“Leave her alone!” exclaimed Bachelard, delighted with the counselor’s misfortune, “she will humbug you again. There is nothing like virtue, understand! It is far better to take a little one devoid of malice, as innocent as the child just born. Then, there is no danger, one may sleep in peace.”

Trublot meanwhile was smoking, leaning against the wall with his legs stretched out. He was gravely reposing, the others had forgotten him.

“If you particularly want it, I can find the address for you,” said he. “I know the maid.”

Duveyrier turned round, surprised at that voice which seemed to issue from the boards; and, when he beheld him smoking all that remained of Clarisse, puffing big clouds of smoke, in which he fancied he beheld the twenty-five thousand francs’ worth of furniture evaporating, he made an angry gesture and replied:

“No, she is unworthy of me. She must beg my pardon on her knees.”

“Hallo! here she is coming back!” said Gueulin, listening.

And some one was indeed walking in the ante-room, whilst a voice said: “Well! what’s up? is every one dead?” And Octave appeared. He was quite bewildered by the open doors and the empty rooms. But his amazement increased still more when he beheld the four men in the midst of the denuded drawing-room, one sitting on the floor, and the other three standing up, and only lighted by the meager candle which the counselor was holding, like a taper at church. A few words sufficed to inform him of what had occurred.

“It isn’t possible!” cried he.

“Did they not tell you anything, then, down-stairs?” asked Gueulin.

“No, nothing at all; the doorkeeper quietly watched me come up. Ah! so she’s gone! It does not surprise me. She had such queer hair and eyes!”

He asked some particulars, and stood talking a minute, forgetful of the sad news which he had brought. Then, turning abruptly toward Duveyrier, he said:

“By the way, it’s your wife who sent me to fetch you. Your father-in-law is dying.”

“Ah!” simply observed the counselor.

“Old Vabre!” murmured Bachelard. “I expected as much.”

“Pooh! when one gets to the end of one’s reel!” remarked Gueulin, philosophically.

“Yes, it’s best to take one’s departure,” added Trublot, in the act of sticking a second cigarette paper round his cigar.

The gentlemen at length decided to leave the empty apartment. Octave repeated he had given his word of honor that he would bring Duveyrier back with him at once, no matter what state he was in. The latter carefully shut the door, as though he had left his dead affections there; but, down-stairs, he was overcome with shame, and Trublot had to return the key to the doorkeeper. Then, outside on the pavement, there was a silent exchange of hearty hand-shakes; and, directly the cab had driven off with Octave and Duveyrier, Uncle Bachelard said to Gueulin and Trublot, as they stood in the deserted street:

“Jove’s thunder! I must show her to you.”

For a minute past he had been stamping about, greatly excited by the despair of that big noodle of a counselor, bursting with his own happiness, with that happiness which he considered due to his own deep malice, and which he could no longer contain.

“You know, uncle,” said Gueulin, “if it’s only to take us as far as the door again, and then to leave us——”

“No, Jove’s thunder! you shall see her. It will please me. True, it’s nearly midnight, but she shall get up if she’s in bed. You know, she’s the daughter of a captain, Captain Menu, and she has a very respectable aunt, born at Villeneuve, near Lille, on my word of honor! Messieurs Mardienne Brothers, of the Rue Saint-Sulpice, will give her a character. Ah! Jove’s thunder! we’re in need of it; you’ll see what virtue is!”

And he took hold of their arms, Gueulin on his right, Trublot on his left, putting his best foot forward as he started off in quest of a cab, to arrive there the sooner.

Meanwhile Octave briefly related to the counselor all he knew of Monsieur Vabre’s attack, without hiding that Madame Duveyrier was acquainted with the address of the Rue de la Cerraise. After a pause, the counselor asked, in a doleful voice:

“Do you think she will forgive me?”

Octave remained silent. The cab continued to roll along, in the obscurity lighted up every now and then by a ray from a gas-lamp. Just as they were reaching their destination Duveyrier, tortured with anxiety, put another question:

“The best thing for me to do for the present is to make it up with my wife; do you not think so?”

“It would, perhaps, be wise,” replied the young man, obliged to answer.

Then, Duveyrier felt the necessity of regretting his father-in-law. He was a man of great intelligence, with an incredible capacity for work. However, they would, very likely, be able to set him on his legs again. In the Rue de Choiseul, they found the street-door open, and quite a group gathered before Monsieur Gourd’s room. But they held their tongues, directly they caught sight of Duveyrier.

“Well?” inquired the latter.

“The doctor is applying mustard poultices to Monsieur Vabre,” replied Hippolyte. “Oh! I had such difficulty to find him!”

Up-stairs in the drawing-room, Madame Duveyrier came forward to meet them. She had cried a great deal, her eyes sparkled beneath the swollen lids. The counselor, full of embarrassment, opened his arms; and he embraced her as he murmured:

“My poor Clotilde!”

Surprised at this unusual display of affection, she drew back. Octave had kept behind; but he heard the husband add, in a low voice:

“Forgive me, let us forget our grievances on this said occasion. You see, I have come back to you, and for always. Ah! I am well punished!”

She did not reply, but disengaged herself. Then, resuming in Octave’s presence her attitude of a woman who desires to ignore everything, she said:

“I should not have disturbed you, my dear, for I know how important that inquiry respect the Rue de Provence is. But I was all alone, I felt that your presence was necessary. My poor father is lost. Go and see him: you will find the doctor there.”

When Duveyrier had gone into the next room, she drew near to Octave, who, so as not to appear to be listening to them, was standing in front of the piano.

“Was he there?” asked she briefly.

“Yes, madame.”

“Then, what has happened? what is the matter with him?”

“The person has left him, madame, and taken all the furniture away with her. I found him with nothing but a candle between the bare walls.”

Clothilde made a gesture of despair. She understood. An expression of repugnance and discouragement appeared on her beautiful face. It was not enough that she had lost her father, it seemed as though this misfortune was also to serve as a pretext for a reconciliation with her husband! She knew him well, he would be forever after her, now that there would be nothing elsewhere to protect her; and, in her respect for every duty, she trembled at the thought that she would be unable to refuse to submit to the abominable service. For an instant, she looked at the piano. Bitter tears came to her eyes, as she simply said to Octave:

“Thank you, sir.”

They both passed in turn into Monsieur Vabre’s bed-chamber. Duveyrier, looking very pale, was listening to Doctor Juillerat, who was giving him some explanations in a low voice. It was an attack of serous apoplexy; the patient might last till the morrow, but there was not the slightest hope of his recovery. Clotilde just at that moment entered the room; she heard this giving over of the patient, and dropped into a chair, wiping her eyes with her handkerchief, already soaked with tears, and