OUT OF TUNE.

“Spirits are not finely touched

But to fine issues.”

IN a certain manufacturing town, of no great size, there lived a musician. For the most part he gained his living by playing at concerts and giving lessons; but he was young, ardent, and clever, and he had always nursed a hope that he might one day be a great composer. He felt a soul of music within him, that wanted to come out and express itself. But, though he had had a complete training in composition, and had written much music and published a little, no one took any notice of what he composed; it was too good to sell well (so he used to say, and perhaps it was true), and he had never had a chance of having any of his larger works performed in public. And he began to get rather irritable and impatient, so that his wife was sometimes at her wits’ end to know how to cheer him up and set him to work once more with a good heart.

Great was the poor man’s delight when one day a letter arrived from the town clerk, to tell him that on the approaching visit of the Prince of Wales to open the new Town Hall, a grand concert was to be given, in which works by natives of the town were to be performed; and that he was invited to write a short cantata for voices and orchestra. A liberal sum was to be paid him, and he was to train his own choir, to have the best artists from London to help him, and to conduct his composition himself. The news put him in such a state of high spirits that now the prudent wife was obliged to pour a little cold water on his ambition, and tell him that he must not expect too much success all at once. But she made him comfortable in their little parlour, and kept the neighbours from breaking in upon his work; and for some time the cantata went on at a flowing pace, until nearly half of it was done.

After a while however the musician’s brain began to rebel against being kept in all day hard at work, and to refuse to keep quiet and rest in soothing sleep at night. It said as plainly as possible—“If you will go on driving me in harness all day long, I shall be obliged to fidget at night, and what is more, it is quite impossible for me to do such good work in the day as I used to. So take your choice: either you must give me repose sometimes, or I must cease to be able to find you beautiful melodies, and to show you how to treat them to the best advantage.” But the musician did not know that his brain was complaining in this way, though his wife heard it quite well; and he went on driving it harder than ever, whipping it up and spurring it on, though it had hardly any strength left to pull the cantata along with it. And all this time he was shutting himself away from his friends, who used formerly to come often and refresh him with a friendly chat in the evenings; he refused to go with his wife and visit the very poor people whom they had been in the habit of comforting out of their slender store; he lost his temper several times with his pupils, and one day boxed a boy’s ears for playing a wrong note twice over, so that the father threatened to summon him before the magistrates and have him fined for assault; and his wife began at last to fear that his stroke of good luck had done him more harm than good.

One morning he got up after a restless night, in which his poor brain had been complaining as usual without being taken any notice of, and settled himself down in the parlour after breakfast with the cantata, feeling worried and tired both in his body and mind. With great labour and trouble he finished the last chorus of his first part, and uttered a sigh of relief. The next thing to be done was to write the first piece of the second part, which was to be an air for a single voice, and was to be sung at the concert by one of the best singers in the country. All the rest of the cantata had been thought out carefully before he began to write; but this song, for which beautiful words were chosen from an old poet, had never worked itself out in his brain so as to satisfy him. And now the poor brain was called upon for inspiration, just at a time when it was hardly fit even to do clerk’s work.

He tried to spur it up with a pipe of tobacco, but not a bit would it budge. Then he took a dose of sal volatile; but the effect of it only lasted a few minutes, and then he felt even more stupid than before. Then he opened the window and looked out into their little back-garden, just as a gleam of sunshine shot down through a murky sky. This made him feel a little better, and he returned to his desk, and sat for a few moments looking at the words which he was to set to music, feeling almost as if he were now going to make a little way. But the sunshine had also made the canary in the window feel a little warm-hearted, and it burst out into such a career of song, that the room seemed to be echoing all over with its strains. And all his own music fled at once out of the distracted composer’s head.

“You little noisy fiend!” he cried angrily, “putting in your miserable little twopenny pipe, when a poor human artist is struggling to sing. Don’t you know, you little wretch, that art is long and time is fleeting?”

He jumped up, took down the cage with an ungentle hand, and carried it into another room, where he drew a heavy shawl over it and shut the door. The canary’s song was stifled, but the musician’s song was not a bit the better for it. And after a while there came another annoyance. The house was small and not very solidly built, and though the room where he was at work did not look out on the street, any street-calls, bands, hurdy-gurdys, or such like noise-making enemies, could be heard there quite distinctly. This time it was a street-boy whistling a tune; it was not a bad tune, and it was whistled with a good heart; indeed the boy put so much energy into his performance, that he must have been in very high spirits. And why did he stop there so long? Generally they passed by, and the tails of their tunes disappeared in the distance, or they turned down the next street. But this one was clearly stopping there on purpose to annoy the composer.

He went softly into the front room, keeping out of sight from the window. He was seized with a desire to wreak vengeance on this tormentor, but he was not quite clear how to do it, and must survey his ground first. Stepping behind the window-curtain, he peeped out between the curtain and the window-frame, and saw a small boy, whistling hard, with a long string in his hand, which descended into the area below. The musician stood on tiptoe, and looked down into the area; it was a sort of relief to him to see what this urchin was about. At the end of the string he perceived a dead mouse, which was being made to jump up and down and counterfeit life, as well as was possible under the circumstances, for the benefit of a young cat of the household, who was lying in wait for it, springing on it, and each time finding it drawn away from her just as she thought her claws were fast fixed in it. This boy was in fact an original genius, who had invented this way of amusing himself; he called it cat-fishing, and it was excellent sport.

The musician suddenly flung up the window, and faced the boy, who seemed by no means disconcerted; he only left off whistling and looked hard at the musician.

“What are you doing with the cat?” said the latter, with all the dignity he could put on. “What business have you to meddle with my cat, and make that infernal din in front of my house?”

The boy began slowly to haul up the string, looking all the while steadily at the composer.

“I say, guv’nor,” he said, with a mock show of friendly interest, “do you know as you’ve got a blob of ink at the end o’ your nose?”

The composer was taken aback. He certainly did not know it, but nothing was more likely, considering how he had been pulling his moustache and scratching his head with fingers which, as he glanced at them, showed some traces of ink. He put his hand involuntarily to his nose, and half turned to the glass over the chimney-piece. There was not a stain there: the nose was innocent of ink. Instantly he returned to the window, but the boy was gone; all that was left of him was a distant sound of “There’s nae luck aboot the house” far down the street. The composer went gloomily back to his study, without a particle of music in his brain; the canary and the whistler had driven it all away. He sat down mechanically at his desk, but he might as well have sat down at the kitchen-table and tried to make it play like a piano.

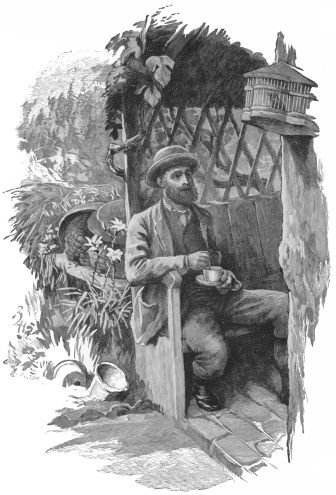

He got up once more, and looked out of the window. The sun was again shining, and the little garden, fenced in between brick walls which caught the sunshine, and enlivened with a few annuals (for it was early summer), did not look altogether uninviting. At the end of it was a little arbour which he had built himself, and a rose tree that he had planted against it was already beginning to blossom. The composer thought he would go and quiet himself down in this little arbour, and try and get his thoughts fixed upon the air he was to write. Out he went, and seated there, began to feel more at ease. After a while he began to think once more of the old poet’s lines; and feeling as if music were coming into his brain again, went and fetched his manuscript and his pen and ink, to be ready in case he should have musical thoughts to write down.

Suddenly there broke in upon his peace the loud, shrill song of a wren. It was close to him, just outside the arbour; and when a wren sings close to you, it pierces your ears like the shrillest whistle ever blown by schoolboy. It was all unconscious of the presence of the composer so close to its nest, which it had built in the branches of the rose-tree that climbed up outside; and it hopped down for a moment on the gravel just in front of the arbour to pick up some fragment of food. The composer’s nerves were quite unstrung by its sudden outburst of self-asserting song; it was an insult to music, to the poet, and to himself. No sooner did the tiny bird appear, as complacent and hearty as all wrens are, than he seized the ink-bottle, and like Luther at Wittemburg, flung it wildly at the little fiend that thus dared to disturb his peace. Of course he missed his aim; of course he broke the ink-bottle and spilt the ink; and alas! when he returned from picking up the bits, a splash from the bottle had fallen in a grand slanting puddle over the neat manuscript of the last page of the chorus which concluded his second part. And as he stood beholding it in dismay, lo! the voice of that irrepressible little wren, as shrill and pert as ever, only a little further off!

If the musician had not quarrelled with his brain, and if the struggle between them had not put his nerves all out of tune—if he had been then the gentle and sweet-tempered artist he generally was—he would have laughed at the idea of such a little pigmy flouting him in this ridiculous way. As it was, he growled under his breath that everything was against him, crushed his hat on his head, took the manuscript into the house and locked it up in a drawer, wrote a hurried note to his wife, who had gone put, to say he had gone for a long walk and would not be back till late, and sallied out of the house where no peace was any longer possible for him.

He walked fast, and was soon out of the town and among the lanes. They were decked with the full bloom of the wild roses, and the meadows were golden with buttercups; but these the composer did not even see. Birds sang everywhere, but he did not hear them. He was just conscious that the sun was shining on him, but his eyes were fixed on the ground, and his mind was so full of his own troubles that there was no room in it for anything nicer to enter there. He was thinking that his song would never be written, for he could not bear to write anything that should be unworthy of those words, or second-rate as music; and it seemed as if his brain would never again yield him any music that he could be satisfied with. “I shall be behindhand,” he thought to himself. “I shall have to write and say I can’t carry out my undertaking; my one chance will be lost, and all my hopes with it. I shall lose my reputation and my pupils, and then there will be nothing left but beggary and a blighted life!” And he worked himself up into such a dreadful state that when he was crossing a river by a bridge, it did actually occur to him whether it would not be as well to jump over the parapet and put an end to his troubles once for all. His mind was so full of himself that for a moment he forgot even his wife and child, and all his friends and well-wishers.

He stood by the parapet for some minutes looking over. The swallows and sand-martins were gliding up and down, backwards and forwards through the bridge, catching their food and talking to themselves. A big trout rose to secure a mayfly from the deep pool below, and sent a circle of wavelets spreading far and wide. A kingfisher flashed under the bridge, all blue and green, and shot away noiselessly up the stream; and then a red cow or two came down to drink, and after drinking stood in the water up to their knees, and looked sublimely cool and comfortable. And the river itself flowed on with a gentle rippling talk in the sunshine, hushing as it entered the deep pool, and passing under the bridge slowly and almost silently—“like an andante passing into an adagio,” said the musician to himself; and he walked on with eyes no longer fixed on the ground, for even this little glimpse of beauty from the bridge had been medicine to the brain, and it wanted more—it wanted to see and to hear more things that were beautiful and healing.

He went on, still gloomy, but his gloom was no longer an angry and sullen one. Through his eyes and ears came sensations that gradually gladdened his heart, and relieved the oppression on his brain: he began to notice the bloom on the hedges and in the fields; and the singing of the larks high in air, though he hardly attended to it, made part of the joyousness of nature which was beginning to steal into his weary being. Presently he came to a little hamlet, hardly more than a cottage or two, but with a little church standing at right angles to the road. The churchyard looked inviting, for rose-bushes were blooming among the graves, and it was shut out from the road by a high wall, so that he would be unobserved there. He walked in and sat down on a tombstone to rest.

He had not been there long, and was beginning to feel calmed and quieted, when there broke out on him from the ivied wall the very same shrill wren’s song that had so wounded his feelings in the morning. It sent a momentary pang through him. There started up before his eyes the broken ink-bottle, the smeared page, the bitter vexation and worry, and the song not even yet begun. But the battle of body and brain was no longer being waged, and as the tiny brown bird sang again and again, and always the same strain, he began to wonder how such cheerful music could ever have so maddened him. It brought to his mind a brilliant bit of Scarlatti, in which a certain lively passage comes up and up again, always the same, like a clear, strong spring of water bubbling up with unflagging energy, and with a never-failing supply of joyousness. And the wren and Scarlatti getting the better of him, he passed out of the churchyard, and actually began to feel that he was hungry.

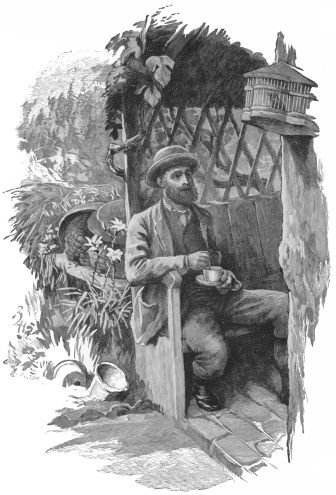

Just across the road was a thatched cottage, standing in a little garden gay with early summer flowers; beehives stood on each side of the entrance, and a vine hung on the walls. It looked inviting, and the musician stepped over the little stile, and tapped at the door, which was open. A woman of middle age came forward.

“Can you tell me,” said he, “whether there is an inn anywhere near where I could get some bread and cheese?”

She answered that there was no inn nearer than the next village, two miles away. “But you look tired and pale, sir. Come in and have a morsel before you go on; and a cup of tea will be like to do you good. Sit you down in the porch and rest a bit, and I’ll bring you something in a moment.”

The musician thanked her, and sat down in the porch by the beehives. It was delicious there!—bees, flowers, sunshine; on the ground the shadows of the vine-leaves that were clustering unkempt above his head; in the distance golden meadows and elm-trees, and the faint blue smoke of the town he had left behind him. Outside the porch hung a cage, in which was a skylark, the favourite cage-bird of the poor; it had been interrupted in its song by the stranger’s arrival, but now began again, and sang with as good a heart and as lusty a voice as its free brethren in the blue of heaven.

“What a stream of song!” thought the musician. “He sings like good old Haydn! We can’t do that now. We don’t pour out our hearts in melody, and do just what we like with our tunes.”

“How that bird does sing.”—

The lark ceased for a moment, and the ticking of the big clock within the cottage suddenly called up in his mind the andante of the Clock Symphony, and the two bassoons ticking away in thirds with that peculiar comical solemnity of theirs; and he leant back in the porch and laughed inside himself till the lark began to sing again. Then he went on mentally to the last allegro vivace, and caught up by its extraordinary force and vivacity, his brain was dancing away in a flood of delicious music, when the woman came out to him with a cup of tea and bread and butter.

“How that bird does sing!” he said to her. “It has done me worlds of good already!”

“Ah,” she answered, “he has been a good friend to us too. It was my boy that gave him to me—him as is away at sea. He sings pretty nigh all the year round, and sometimes he do make a lot of noise; but we never gets tired of him, he minds us so of our lad. Ah, ’tis a bad job when your only boy will go for to be a sailor. I never crosses the road to church of a stormy morning and sees the ripples on the puddles, but I thinks of the stormy ocean and my poor son!”

The musician asked more about the sailor; and he was shown his likeness, and various relics of him that the fond mother had cherished up. And when he rose to go he shook hands with the woman warmly, and told her that he would one day bring his wife and ask for another cup of tea. Then he started off once more, refreshed as much by the milk of human kindness as by the tea and bread and butter.

He soon began to feel sleepy, and looked for a quiet spot where he could lie down in the shade. Crossing two or three fields he came to a little dingle, where a stream flowed by a woodside; on the other side was a meadow studded with elms and beeches, and under the shade of one of these, close to the brook, and facing the wood, he lay down, and was soon fast asleep.

He was woke up by a musical note so piercing, yet so exquisitely sweet, a crescendo note of such wonderful power and volume, that he started up on his elbow and looked all round him. It was not repeated; but in a minute or two there came from the wood opposite him a liquid trill; then an inward murmur; then a loud jug-jug-jug; and then the nightingale began to sing in earnest, and carried the musician with him into a kind of paradise. He did not think now of the great composers; this was not Beethoven or Mozart; this was something new, and altogether rich and strange. Every time the bird ceased he was in suspense as to what would come next; and what came next was as surprising as what went before. At last the nightingale ceased, and dropped into the thick underwood; but the musician lay there still, and mused and dozed.

At length he started up and looked at his watch; it was past seven o’clock. He hurried off homewards in the cool air, refreshed and quieted, thinking of nothing but the things around him, and now and then of the cottage, the lark, the brookside, and the nightingale. But presently there came into his recollection the old poet’s lines, and he repeated them over to himself, for they seemed in harmony with his mood, and with the coolness, and the sunset. Then as a star comes out in the twilight, there came upon his mind a strain worthy to be married to immortal verse; like the star, it grew in brightness every moment, until he could see it clear and full. In a moment paper and pencil were in his hand, and the thought was fixed beyond all fear of forgetting. By the time he reached home, the whole strain was worked out in his mind, and he wrote the first draft of it that same evening, as he sat contented in his parlour, with his wife sewing by his side.

After this nothing went wrong with the cantata. It was finished, it was a great success, and the music to the old poet’s words was enthusiastically encored. The audience called loudly for the composer, and the Prince of Wales sent for him, and congratulated him warmly. And the day after the concert he took his wife out into the country, and they had tea at the cottage; the lark sang to them, the flowers were alive with murmuring bees, and the musician’s mind was free from all care and anxiety.

As they sat there, he told his wife the whole story of that eventful day, not even keeping from her the thought that had passed through his mind on the bridge. When he had finished, she laid her hand on his, and said, in her comfortable womanly way—

“You were out of tune, dear, that’s what it was. And you can’t make beautiful music, if you’re out of tune: everything you see and hear jars on you. You must tell me next time you feel yourself getting out of tune, and we’ll come out here and set you all right again.”

They went comfortably back to the town, after a day of complete happiness. As they neared their own door, they saw the street-boy leaning again over their railings, and cat-fishing as usual in the area. He was whistling with all his might; but this time it was “Weel may the keel row.” They took it as a good omen; and the astonished urchin found himself pounced on from behind, carried into the house by main force, and treated with cake, and all manner of good things, while the musician sat down to the piano and played him all the beautiful tunes he could remember. He did not come to fish in their area any more after this; but a few days later he was heard whistling “Vedrai carino” with an abstracted air, as he leant over a neighbour’s railings, amusing himself with his favourite pastime.