A JUBILEE SPARROW.

ON the evening of the 21st of June, 1887, a cock sparrow sat on the roof of St. James’s Palace, in London, gazing down now into St. James’s Street, now into Pall Mall, where the preparations were almost finished for the Jubilee which was to take place next day. Flags were being fixed at all the windows, and Chinese lanterns hung out for the illuminations; seats were being everywhere contrived for the spectators, and all was bustle and activity. Every one seemed in good humour; it was plain that all were bent on showing the good Queen who had reigned fifty years without a blot on her fair fame, that their hearts went out to her in sympathy and goodwill. Yet any one skilled in the ways of birds, who could have seen the sparrow as he sat there, would have judged from the set of his feathers that his mind was very far from being at ease.

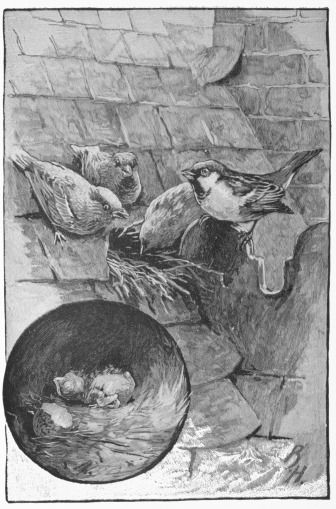

“There’s no time to lose,” he muttered to himself; “she’ll have to sit all day and all night, or we sha’n’t do it after all.” He flew down to a snug corner behind a tall brick chimney looking to the south, where his wife was sitting on a nest with four eggs in it.

“My dear,” he said; “you mustn’t leave the nest to-day; you know my hopes and wishes; you will disappoint me dreadfully if you can’t manage to hatch out an egg to-morrow. It really is our duty, as we live in a palace, to have a nestling hatched on the Jubilee day. Why, my people have lived here ever since the Queen came to the throne, and one of my ancestors was born on the very day of her accession! we must keep up the tradition, and, my dear, it all depends on you. Remember, I picked you out of a whole crowd down in St James’s Park, and I made no inquiries about your connections; you may have come from a Pimlico slum for all I know. But I saw you had good qualities and I asked no questions. Now do try and do yourself justice. Sit close, and don’t on any account leave the eggs, and I will bring you all sorts of good things from the Prince of Wales’ own kitchen.”

The hen sparrow fluttered her wings a little and meekly assured her husband that she would do her best. “It’s hard work,” she added; “my poor breast is getting quite bare, and I’m so hungry. But I’ll sit till August to please you, you beautiful and noble bird.”

“That’s right,” said the cock sparrow, much pleased; and indeed he was a fine bird, with his black throat and blue head, and mottled brown back. He flew straight down to the back door of Marlborough House, where the Prince of Wales lives (he patronized no human beings but royalty and the aristocracy), and finding the usual supply of crumbs and scraps put out by the royal kitchen-maid, he made a good meal first himself, and then set to work to carry his wife her supper.

The day was very hot and very long, and the warmth greatly helped the weary hen in performing her duties. She stuck to her post all the time she was having her supper, and she knew that her eggs would soon be hatched; but neither she nor her husband had quite reckoned for the warmth of the day. Just when the cock was going to roost, well satisfied with his wife, and certain that his fondest hopes would be realized to-morrow, crack, crack! peep, peep! out came a tiny sparrow from the egg in the warmest corner of the nest, full three hours before the Jubilee day was to begin!

She called her husband—

“Oh what a little darling,” she cried. “Oh, what a lovely little yellow beak! and what a sweet crumply little red skin!” And she forgot all about the Jubilee.

“What a horrid little wretch you mean,” said the cock sparrow. “An impudent, pushing little ugly brute, to come out just at the wrong time! And he would have seized it and thrust it out of the nest, if the poor delighted mother had not spread her wings quite over it.

“Oh, don’t be so cruel,” she said, “please don’t; I’ll hatch another to-morrow, if I possibly can. I’ll sit all day, and never even want to go and see the procession, as you promised I should.”

“Very well,” said the cock. “You stay here and sit close till you’ve hatched another. Not one bit of food shall that little monster have from me, till his brother is born. And if he is not born to-morrow, it’ll be very much the worse for you, my dear!”

He went to roost again, and his wife cuddled herself down once more on the eggs, and fondled her little new-born chick. All night long the hammering of boards went on in the streets below, where the preparations were being finished for the procession, and the poor hen passed a very sleepless night. Her body was tired, and she was dreadfully afraid of her husband’s anger, if she should fail in her duty. “But, after all,” she thought, “one must go through a good deal if one is to have a husband who lives in a palace and is connected with the highest families in the land!”

The next day was, as we all remember, another very hot one. The sun blazed down upon the poor hen sparrow, who was obliged to keep sitting close all day, until she really thought she must have died with heat and anxiety. Not for one minute would her husband allow her to leave the nest and look at the processions. He perched on a chimney whence he could see her on the nest, and also see the procession coming through from Buckingham Palace; and he described it all to her from his chimney, but what was the good of that? She might just as well have read it in the newspapers the next morning.

All day long she sat on those three remaining eggs, and it really seemed as if they would never crack. The cock got more and more angry and impatient. “We shall be disgraced,” he cried, when the processions were all over, and still no second chick; “we shall be disgraced, and we shall have to leave the Palace. I shall, at least; you may stay if you like: you have no connection with the royal family and no sense of shame.”

The hen could say nothing. She was doing her best, poor thing, and she could do no more. Hour after hour passed, and still no egg burst. At last, as the big clock on the Palace struck seven, crack! peep!—a second little sparrow poked out its bill into this wicked world.

The cock sparrow was in a state of wild excitement. He pushed his wife off the nest, and declared he was going to take charge of it all himself.

“Oh, what a beauty!” he exclaimed; “so different from that other little wretch! Fly at once, my dear, to Buckingham Palace, and let Her Majesty know. She’ll be delighted. And only think if you were to bring back some crumbs from the hand of royalty itself! I’ll take care of it meanwhile.”

Off flew poor weary Mrs. Sparrow on her errand. But when she got to Buckingham Palace, she didn’t know how to find the Queen; so she flew down into Palace Road, and picked up a crumb or two in front of a baker’s shop there, which she brought home in her beak.

“Well done!” cried her husband, without waiting to ask where they came from. “Crumbs from Her Majesty’s own hand! wasn’t she delighted? Did she say it was to be called ‘Jubilee,’ in honour of the day? Of course she did. Jubilee he shall be; and there isn’t another young one in London to compare with him.”

A Jubilee Sparrow.—

There was indeed a terrible to-do made about this little nestling, which was ugly enough in the eyes of every one but its parents. The news of it spread about, and from all parts of London sparrows came to see it. All sorts of tales were told of it, and the further you got from St. James’s, the more wonderful they were. In the Strand they told how the bird broke the egg as the Queen was passing by, and how Her Majesty happened to look up to see what o’clock it was, and seeing the old sparrow on the roof, bowed to him most graciously. Further east, the sparrows of St. Paul’s Cathedral narrated how a bird had been born on the roof of Buckingham Palace, just over the Queen’s own bedroom window, and how Her Majesty, on hearing the news, had sent for a long ladder, and ordered the Lord Chamberlain to take up some choice dainties to the parents on a plate of solid gold. And far away in the East-end, the black and sooty sparrows who inhabit those parts, and who firmly believe themselves and their race to be the most important part of the whole population of London, were much stirred by a rumour that a sparrow had been born in the West-end, which had been declared by the Queen to be heir to the throne, and that the days of the rule of man were coming to an end, and the sparrows were going to have it all their own way.

Thus the fame of little Jubilee spread over the whole of London, and even into the country, for the sparrows that were going out of town for the summer carried the news with them, and the whole world of sparrows were in a few days chattering and quarrelling about it.

Meanwhile Jubilee was being stuffed with all sorts of good things, and in the second week of his existence very nearly died of over-eating. If he had been fed with wholesome flies, like the others, he would have taken no hurt; but his father was always bringing bread-crumbs from the Prince of Wales’s back-door, and these, when forced down the wide-open yellow throat of poor Jubilee, were apt to choke him sadly.

“Never mind,” said the father, “it will all help to strengthen his blood, and make him a fit neighbour for kings and princes!”

Luckily the entreaties of his mother, who declared he would die if he were not fed properly, had some effect, and Jubilee grew to be a fledgling without falling a victim to his own greatness. When he was ready to leave the nest, the others, who had been carefully brought up to consider themselves nobodies, and to bow before Jubilee in everything, were told to go and shift for themselves—their mother might look after them if she liked. As for Jubilee, he was to be under his father’s care for a while longer, and to be introduced to the world where he was to cut such a great figure. He had by this time, as you may suppose, come to think a good deal of himself; and to say the truth, there was no such conceited young jackanapes of a sparrow to be found in the whole of London. But all the parent sparrows had taught their young ones to look up to him, and his high mightiness had things pretty much his own way.

The royal families being by this time gone out of town, it was not possible to have him presented at court; so the father sparrow was obliged to be content with taking him to the water in the park, to introduce him to the ducks. He did indeed drop a hint or two about going to Windsor Castle when Jubilee should be strong enough; but he had never been so far himself, and had some doubts in his own mind as to his reception by the rival sparrows of that royal residence. Supposing they had produced a Jubilee sparrow there too! It might be wiser not to go so far a-field.

The ducks were very gracious to Jubilee. They informed him that they were the property of the state, and under the especial care and patronage of the nobility and gentry. They lamented that the royal princes and princesses did not often come to feed them, and told him how two centuries ago, that excellent monarch Charles the Second had made it a regular practise and duty to walk in the park for the purpose of throwing bread to the ducks of that day. They said that Jubilee might come every day and share the things that were given them.

So Jubilee led a happy life for a while in the society of the ducks, and became more vain than ever. He was very bold, and would hardly get out of the way of the passers-by. And this vanity and boldness led to a turn in the fortunes of this sadly spoilt young bird, which it is now our painful duty to relate.

One day he was left by his father with the Ducks, and was listening to their aristocratic conversation, taking a bathe in the water now and then, and preening himself in the sunshine, when two very ragged and dirty boys came by. One of them had a large hunk of bread which he was eating, and as he passed the ducks he threw them a few crumbs. The ducks did not mind where they got their bread; whether it were given them by a monarch or a street-boy was all the same to them; and young Jubilee of course did as they did. So it came to pass that he flew down from the bush where he happened to be perching at the moment, and dexterously picked up a crumb which had fallen just at the edge of the water.

The boys, seeing this, threw him another and then another, nearer and nearer to themselves; and Jubilee, in all his pride and self-confidence, came close up to them. Suddenly one of the boys whipped off his cap, and flung it with such good aim, that it knocked over poor Jubilee, and half stunned him; the other boy instantly pounced down upon him, and he was a prisoner in a pair of grimy hands. He called out loud to the ducks, but they only said “quack-quack,” and went off to the other side of the water, as they saw no more bread was coming.

“Serves him right!” said an old drake: “you ducks made such a fuss about that little piece of impudence, that he was getting quite unbearable.”

Meanwhile, to prevent his escape, as he struggled and pecked with all his might, his captor put him into his pocket; where he found himself in company with a morsel of mouldy cheese, a half-eaten apple, two or three bits of string, the cork of a ginger-beer bottle, the head of a herring, and the bowl of an old clay pipe; all of which, combined with the dirtiness of the pocket itself, made up such a smell that Jubilee will never forget it to the last day of his life. The only comfort was that there was one place where light showed through the pocket; and for this he made and tried to struggle out. The boy, feeling him struggling, gave his pocket a slap, which quieted master Jubilee for a time; but after a while he recovered and began to make for fresh air again. This time the other boy saw his beak coming out and warned his companion in time; so Jubilee was taken out, and they tied the poor prisoner’s legs together with one of the bits of string, and put him into another pocket in company with a dead mouse. And now he had to lie still and take things as they came. He was tired out with fear, and struggling, and hardly had life enough left in him to be angry or cry out.

It was some time before he was released from the company of the dead mouse. When he was taken out of the pocket, he found himself in a dark and grimy room, with hardly any furniture, no fireplace, and only one small window high up in the wall. What a change from St. James’s Palace! He was in fact in the cellar of a small house in a back street in Westminster, where the father of the boys lived: a very poor man, whose wages were so small, even when he was lucky enough to get work, that he could only afford to rent a cellar; and here he and his wife and their two boys lived.

When the door was shut, Jubilee’s legs were untied and he was then put into a small box, in the lid of which one of the boys had bored a few small holes to give him air. Some crumbs were dropped through the holes, but they quite forgot to give him water, and the poor bird had to suffer great torments of thirst. When night came at last and the family lay down on their wretched mattresses in the corners of the room, Jubilee expected to get some sleep; but even this was denied him. No sooner was all quiet than the rats began to prowl about the room; and you may be sure they soon smelt out Jubilee. They came and climbed up on to the box, and when they heard him inside, they began to gnaw the wood between two of the holes. Luckily the nights were still short, and the poverty-stricken family were stirring early, or they would have got at Jubilee before morning. Even as it was, the poor bird, who used to sleep so peacefully after a good supper on the roof of the Royal Palace in the snuggest corner of the nest, had to spend his whole night within a few inches of half-a-dozen hungry monsters, who were thirsting for his blood. He was almost out of his mind by morning.

The boys had each a piece of bread given them for breakfast, some crumbs from which they gave their prisoner; and at the instance of their mother, they also gave him some water, and Jubilee felt a little better, and began to forget about the rats. Suddenly there came a knock at the door. The father had gone to work; the mother opened it. A man in uniform came in. Jubilee thought it must be a special messenger from the Queen, come to demand his instant release.

But it was only the School Board attendance officer, who had come to see why the boys were not at school. They shrank into a corner and presently made for the door, but the officer was too quick for them. He told their mother that he did not wish to have the father fined, and that if the boys would go to the school with him at once, and promise to go regularly, he would not summon him. The boys were frightened and went off with the officer: and Jubilee was left alone with the mother, who now began to try and clean up a bit, and make the room tidy; though, indeed, poor thing, she was too thin and starved to do any real work.

Soon she came to the box where Jubilee was.

“Ah, poor bird!” she thought to herself, “you have come out of fresh air, and away from kind friends, just as we did when we came to this dreadful London. Oh, why did I ever leave the village, and father and mother, and the orchards, and the meadows where we used to gather buttercups and tumble in the hay?” And she sat down on a broken chair by Jubilee’s box, and thought of the sweet air of the country, and wiped away a few slow tears with her apron. At last she got up, and took the box in her hands. “He’ll only starve here,” she thought, “and the rats will get at him. I’ve a great mind to let him go.” But then she thought how vexed the boys would be, and she gave up that idea. If she could only sell him they might all be the better for it. She would try and sell him for sixpence and they would buy a fourpenny loaf, and the boys should have a penny each to console them for the loss of their bird. She took him down the street in the box, turned down another street, and offered him at a shop where numbers of birds in cages were hanging in the window.

“Will you give me sixpence for this bird?” she asked. A pang went through Jubilee; to be sold for a sixpence, and he a royal bird!

The shopman, who was in his shirt (and very dirty it was), and had an evil face, and a short stubbly gray beard, looked with great contempt at Jubilee.

“Sixpence,” he shouted; “why, it’s only a sparrow!”

“Oh,” thought Jubilee, “if I could only tell him that I am a Jubilee sparrow, the only one in London, and worth a thousand times more than my weight in gold!” He had heard this so often from his father, that he at last had come to believe that if ever he really were to be sold they would weigh him and multiply the result by a thousand.

“Sixpence!” cried the shopman. “Sparrows are dear at a penny!”

The poor woman was sadly disappointed, and so indeed was Jubilee. She offered to sell the box as well, and after some bargaining, Jubilee and his box were handed over to the man for the sum of threepence, on which the starving family dined that day, and were thankful too.

Jubilee had not been long in the shop when the evil-faced man opened the box cautiously and seized him before he could escape. Once more his legs were tied together, and he was taken into a little dingy back room and laid upon a table. Then the man shut the door, lit a gas-lamp, and took out some paints and washes; and setting a canary in a cage before him, began to paint Jubilee’s feathers to imitate it.

“What a fat little brute you are,” he said, as he poked his dirty finger into the poor bird’s stomach. “But we’ll soon take that down; we’ll soon starve you into a nice slim canary. No more fat living for you, you little pig.”

Every feather of Jubilee’s wings and tail had to be painted separately, and washed before it was painted; and the poor worn-out bird had to lie there on the table all that day with his legs tied, and was given nothing to eat. After it was all over he was untied and put in a small cage, but kept in the same dingy inner room, away from the street. Two days later he was taken out again, and the whole process had to be gone over once more; and all this time he was getting thinner and thinner. It was a week after he had been sold, before he was pronounced fit to be taken into the shop, and hung in the window in his cage; a label was tied on to it on which was written—

“Canary, a Bargain.

“Warranted Sound. Only 3/6.”

Poor Jubilee! He was at least worth three and sixpence, and his affairs were beginning to go up again. If he could only have the luck to be bought by one of the royal family, all might be well again. But it was not to be. And for a long time nobody even offered to buy him. A fat bullfinch was sold, and Jubilee was quite glad to get rid of him; he was so fat, and so proud of his portly red waistcoat. Linnets and Goldfinches went, and others took their places, and there was always a pretty brisk sale of canaries. But Jubilee was neglected, probably because he used to sit on his perch and mope and ruffle his feathers, from hunger and hatred of the world. He looked sulky, and of course he never sang; so the customers would have nothing to say to him. It was a sad downfall for him, to sit in a cage all day and mope, and have faces made at him by street-boys, who loved to flatten their noses against the window and make all sorts of horrible noises and cat-calls, until the old man ran out with a stick and drove them away. But hunger and misfortune had done Jubilee some good, though it had made him very miserable. He had lost all his old pride, and had had all the nonsense knocked out of his head which his foolish father had stored up there.

One day he was sitting on his perch, dull and listless as usual, and terribly annoyed by the shrill singing of three canaries who were in the window with him, and were always making fun of him because he was only a sham canary and couldn’t sing; when two boys stopped at the window. They were of quite a different kind from any who had been there before; they did not flatten their noses against the glass, or make horrible noises; they wore good clothes, and had broad white collars which were quite clean, instead of dirty old handkerchiefs. They looked a good deal at Jubilee, and were evidently talking about him; but he could not hear what they said. At last they came into the shop and offered the old man two shillings for him.

“Make it half-a-crown,” said he, “and you shall have him;” for he was anxious to get rid of Jubilee. He might begin to moult, or the paint might wear off; and then there might be mischief.

The boys consented to give half-a-crown, and took Jubilee away with them. How glad he was to get out of that shop! Surely better times were coming! He was once more in the hands of the aristocracy, and certainly they handled him much more gently than the street boys. They carried him to a big house in Belgravia, put him in an empty cage, and began to examine him closely. Then they took him out and turned up his feathers.

“I thought so,” said one: “I told you so when we were looking at him through the window. That fellow’s a regular old thief. It’s nothing but a common sparrow. Run and ask father to come and see him.”

The other boy soon returned with a kind-looking gentleman, who laughed when he saw Jubilee, and told the boys they were lucky to have caught a well-known thief and impostor. Then he sent for a cab, took the cage and the boys, and drove down to the street where the old man lived, taking up a policeman on the way. And in another half-hour Jubilee found himself at a police-station; he was put in a sunny window, and the paint partly washed off him, the old man was locked up in a cell, and the gentleman and the boys were to come next day and give evidence.

The next day Jubilee was brought into court in his cage. It was not very pleasant; for he was half yellow and half his natural brown, and all the people laughed at him when he was handed up to the magistrate to be looked at. But a kind-hearted policeman, who had taken care of him the evening before, and given him seeds and water, had pity on him, and took him out of court as soon as he had been looked at, and washed the paint quite off him, and put him back in his sunny window. The case was soon proved, and when the old man had been sent away to prison for obtaining money on false pretences, the policeman asked the boys if he might keep the bird, as it was only a sparrow, and his sick wife would be very glad of it to keep her company while he was out on his beat. The boys gladly let him have it, and Jubilee was once more carried off in his cage to a new residence.

This was a small two-storied house in Pimlico. The policeman carried him up-stairs to his wife who lay ill in bed.

“Ah, Harry dear,” said she, “I’m so glad to see you; I’ve been waiting so long for you. I thought the morning would never come to an end. And what have you got there?”

“Something to make the time go quicker for you,” said the policeman; and he put the cage down on his wife’s bed, and told her the story of the sparrow.

“Poor bird,” said she, “poor thing. I can feel for him, as I’m caged up too, and can’t get out into the fresh air. But thank you, Harry, for thinking of me. He’ll be a companion to me, these long dreary mornings. But what shall we call him?”

“Well,” said Harry, “I reckon he’s about two months old; and to-day’s the 20th of August; so that just about takes us back to Jubilee day. I think he must have been born very near about the Jubilee. Let us call him Jubilee.”

And Jubilee felt that he was among friends, for now he had his right name, and was made much of, and was really of some use. And the policeman’s uniform was consoling too: for it brought back to his mind St. James’s Palace, and the policemen walking up and down the street below, and the scarlet-coated sentinels marching to and fro in front of the Prince of Wales’s gates.

And so two or three weeks went by, and Jubilee sat on his perch, and was fed well with seeds, and wished he could have sung like the canaries to show his gratitude and make the time pass quicker for the suffering wife. She grew paler and paler, and wearier and wearier, and seemed to take pleasure in nothing but Jubilee, and in looking for the time when her husband should come home. She would take the bird out of his cage, and he would hop about on the bed, and take seeds and crumbs out of her hand. He did not want to escape, and meet with new perils and adventures. Never had Jubilee been so happy before.

One day the doctor came, and told her husband that if his wife was ever to get well, she must go into the country for fresh air. It was hard on Harry, for he could not go with her; he must stay in London, and earn his living. But he took his savings out of the bank, and with these he contrived to get his wife taken to Victoria station, and thence in the train to the Sussex village where her parents lived. And of course Jubilee went with her.

I cannot stop to tell the wonders of that journey for Jubilee, or the delight of getting into pure fresh breezes among the Sussex downs. He was put into a window in an old red-brick cottage, where he soon learnt to forget all about London, and the pride of his early days, and all the horrors he had gone through. And, in spite of his being only a sparrow, and having never a song to sing, he was able to soothe the sick wife’s weary hours, and perhaps loved her as dearly as she loved him.

But she got no better; and one day the doctor said that a telegram must be sent at once to fetch her husband from London. When he came in the afternoon, she was lying unconscious, with Jubilee on a chair beside the bed. Jubilee did not know what followed; but before it was dark the policeman had taken his cage to the window and opened the door, saying in a voice that trembled as the bird had never heard it tremble before—

“We shall not want you any more, little Jubilee; go your way, and take our thanks with you.”

Jubilee flew out of the cage into the free air. What has since become of him I cannot tell you. But we may be sure that he did not go back to the perils of London streets, or to the pride and glory of a royal palace.