CHAPTER XVI.

WANTED—A NICE SOMEBODY.

When Max again looked out on the world with seeing eyes, he was lying upon his own bed, a fact which for the moment puzzled him exceedingly. Because cool air and soft sunshine were coming in at the open window; and while it was yet day, Max had been wont to work. As he still scolded himself lazily for a good-for-nothing lie-abed, and almost resolved to rise that very minute, his blinking eyes caught sight of a dark mass which resolved itself slowly into the definite shape of humanity, and became the motionless figure of a man.

“Dad!”

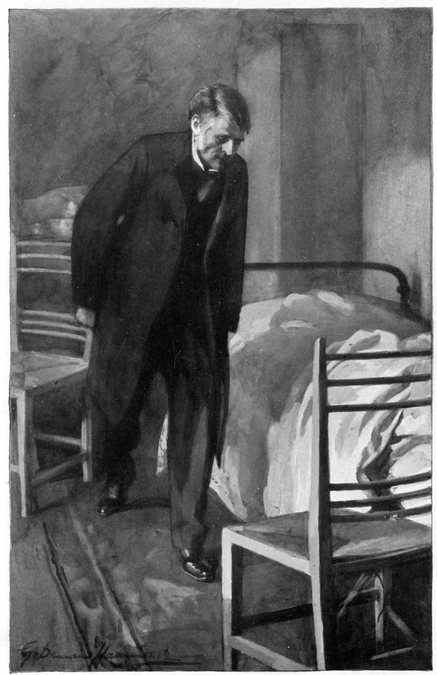

The figure moved, rose, came forward with the painful caution of dreary suspense. Dr. Brenton had doubted his ears, and Max’s eyelids were together again. But gradually they parted, tardily but surely, and Max’s lips smiled.

“THE FIGURE MOVED, ROSE, CAME FORWARD WITH THE PAINFUL CAUTION OF DREARY SUSPENSE.”

The boy heard a low-breathed murmur of thanksgiving.

“Dad!”

“Ah!—Max!...”

Round the corner of a big screen near the door came the eager face of a boy. Just one peep at that other boyish face on the pillow, and then Austin’s vanished. A minute later its owner, on shoeless feet, was dancing a wild jig of enthusiasm on the landing outside. For the great London specialist, Sir Gerald Turner, had said that if, within a certain time, Max recovered consciousness, there might be a chance for his life. And Austin had firm faith in that “chance”.

Sir Gerald had found it convenient to spend a country holiday with his brother, Betty’s father, and might be relied on to be within hail. Max’s case was interesting, and Sir Gerald liked Dr. Brenton. So now Austin, with one brief word to Janet, found his boots, dragged them on somehow, and flew to summon the famous physician. Sir Gerald came at a pace which tried Austin’s patience to the last degree; but as the man was not to be hurried, the boy ran in advance, and wondered as he went what it could feel like to give a verdict for life or death.

Dr. Brenton came to meet his coadjutor, and led him upstairs. The two friends, speaking in whispers, passed out of Austin’s ken. Then the boy, studying his watch, learned that Sir Gerald could actually be heartless enough to keep him in horrible uncertainty for a good ten minutes, and wondered how London could produce and tolerate such a monster. The distant hum of voices heard murmuringly through Max’s window overhead was so intolerable that Austin covered his ears with his hands as he rocked to and fro on the doorstep. Thus he was taken by surprise when a hand was laid kindly on his shoulder, and a voice said gently:

“Be comforted, my boy. Your playfellow is better: he is going to pull through.”

Austin’s wild shout of joy made Max stir in his health-giving sleep; but after all it did no harm, and carried to a little knot of waiting Altruists the first glad prophecy of better things to come.

Max improved slowly, and at length reached a point of improvement beyond which he seemed unable to go. No one was more disturbed than he that this should be the case. His father was palpably uneasy at leaving him, and yet work must be attended to. His own pensioners were doubtless in need of him, though the entire body of Altruists had placed themselves unreservedly at his service.

Through the cloudless days of a beautiful May the Doctor’s son struggled back to life, and learned afresh how sweet a thing it was. He never was lonely, for some boy or girl was always at hand to look after food and medicines, tell stories, and invite orders. On his own behalf Max was not exigent; but his comrades found out, during those days of vicarious work among the sick and sorry of Woodend, how busy a person “the young Doc” had become, and how many of his glad boyish hours must have been given freely to the helping of others.

“Max was an Altruist long before we started our Society,” remarked Frances meditatively. “I don’t know how he managed to do all he did.”

“‘Busy people always have most time,’” said Betty sententiously.

“Will Max ever be busy again, I wonder?” questioned Florry. “Oh, poor Max!—if he doesn’t get well! I heard Dr. Brenton tell Papa that Max didn’t get on a bit, and that he had been so badly hurt.—Oh, Frances! wasn’t it cruel?”

“Yes; but Max is a hero, and we’re proud of him. And he’s quite brave about it. If he fretted, he wouldn’t have half so good a chance; but since he’s plucky and quiet he will surely get well some day. Meanwhile, we can take care of all his ‘cases’.—I dressed a burn to-day,” finished Frances triumphantly. “The child had come to see Max—just fancy—and I took him in, and Max showed me how to do it.”

“We’ll start an ambulance class, and beg Dr. Brenton to teach us,” said Betty. “I should like it. I’m going to be a doctor some day, and live in Harley Street, and be rich and famous, and cure all the people nobody else can cure;—I’ll be just like Uncle Gerald.”

“And Florry will be rich and famous too,” sighed Frances; “she’ll write hooks and plays and be as great an author as you will be a doctor. Oh, dear! I sha’n’t be anybody particular. I’ll just have to stay at home and help Max with his easy cases.”

“I can tell you something more about Max,” said Betty. “Uncle Gerald says Dr. Brenton ought to send him away yachting with somebody who would take great care of him, and then he would get well a great deal sooner. I’m on the look-out for a nice Somebody to do it. I’ve a cousin who has a yacht, and I wrote to him, and what do you think the wretch replied? ‘Catch me plaguing myself with an invalid boy!’ I sha’n’t speak to him when he comes here again.”

“I wouldn’t,” said Florry, with equal determination.

“He doesn’t know Max,” said Frances.

“We will ask all the Altruists to ‘look out for a nice Somebody’ to take Max a sea-voyage,” said Florry. “I dare say we shall soon find someone. Now, good-bye, girls; it’s my turn to be nurse. I’ve a lovely story by Stanley Weyman to read to Max, and I’m aching to begin it.”

If the care and service of his friends could have cured the sick boy he would have made a wonderfully quick recovery. As it was, they certainly helped him loyally through the long days of his pain and weakness; and the persistent cheerfulness of their prophecies as to his future coloured insensibly his own thoughts, and made them usually bright and always contented. Then, though the details of Baker’s capture by a band of Woodend villagers, and his exemplary punishment at their hands, were still withheld from him, he had the relief of knowing that the brutal rascal of Lumber’s Yard had been packed off to America, with a threat of legal proceedings should he dare to reappear in Woodend; and that Bell Baker, free of his tyranny, was developing into a good mother and tidy housewife. Max’s friends found her as much work as she could do; and the Altruists helped her judiciously with extra food and clothing for her little ones.

Moreover, the Woodend gentlemen held a meeting, at which they said many pleasant things about the Doctor’s son, and many serious ones about the condition of the worst part of their village. Edward Carlyon gave his testimony; and it was resolved to attempt the purchase of Lumber’s Yard. This plan was actually carried out almost immediately; and a few months later the “Jolly Dog” and the surrounding wretched dwellings were pulled down, and Lumber’s Yard was no more. Instead, the proud villagers beheld a row of pretty cottages about an open green; and to the small colony was given, by universal vote, the name of young Max Brenton.