CHAPTER XVII.

LESSING OF LESSING’S CREEK.

“Things are looking up, or else the world is coming to an end. Jim has a visitor.”

“Truly?”

“On my word of honour. I say, Frances, he’s such a quaint chap to look at.”

“Somebody else is quaint to look at. I hope you weren’t in your shirt-sleeves when you answered the door?”

“Well—hardly. I believe I wore a complete shirt, likewise a pair of breeks.”

“Run away, boy. I’m busy.”

“So am I—awful. But in the goodness of my heart I just looked in to bring you the news. The fellow told me his name was Tom Lessing, of Lessing’s Creek Farm, Douglas River, Australia. Pretty wide address. He asked for Jim, and said Jim would be sure to see him, so I sent him along to the smithy. But first, as I didn’t want to miss a chance, I inquired if he had happened to meet Mr. Walter Keith—thinking that he would have run across Cousin Walter as likely as not. But he hadn’t.”

“That was remarkable. Australia, as you observed, is a wide address.”

“Well, there was no harm in asking. I hope Jim will invite Tom Lessing, of Lessing’s Creek Farm, to dinner. I’d love to hear a backwoodsman talk. I’d love to go to Australia. Isn’t it odd of Jim not to long to be a colonist? He says he wouldn’t like it a bit.”

“Cousin Walter hasn’t particularly enjoyed being a colonist, Master Adventurous.”

“Oh, that’s because he didn’t learn a trade before he went, and because he didn’t understand sheep-farming, and because he’s a bit of a duffer all round! Now, Jim’s got a kernel in his nut—”

“Austin!”

“Well, brains in his cranium, then. I’m off to peep in on Tom Lessing, of Lessing’s Creek Farm.”

“No, dear, don’t. Perhaps he and Jim are old friends.”

“Yes, they are. He said so. He said a jolly lot in two minutes, I can tell you.”

“Then I wouldn’t pry, Austin. They may have a great deal to tell each other.”

“Well, I won’t pry. I’ll just stroll past the smithy.”

“I thought you were so fearfully busy?”

“So I am. I’m busy keeping you posted up in the latest intelligence.”

“Mamma wants some peas gathered. Get them for her, there’s a dear.”

“None of your blarney! You want to watch over my manners by keeping me in sight. Not a bit! Tom Lessing, like a magnet, lures me to Lessing’s Creek Farm, Douglas River, Australia.”

Austin walked with dignity out by the backdoor, but presently put his head in again, and remarked:

“Of course I’ll gather the peas—enough for five!”

Mrs. Morland was seated shelling peas in the orchard,—it was a warm June morning,—when her stepson, walking quickly over the short, sweet-smelling grass, came to her side.

“Can you spare a minute?” he asked with his old nervousness. The sight of his stepmother taking part in the day’s household work always increased his uneasy sense of his own shortcomings.

“Oh, yes! Have you anything to tell me, James?”

“Just that an old friend has come to see me, and is still here. He’s waiting for me in the smithy. Tom Lessing and I used to be great chums once on a time, though his people were better off than mine. He went out to Australia four years ago, and he has done very well.” Mrs. Morland heard a slight sigh. “He always was a very capable chap, and he has a splendid farm out there now. I—I think the children would like him; he has seen such a lot. Please, would you mind very much if I kept him to dinner?”

“Is he very rough? I do not mean to hurt you, James; but you know I have Frances to think of.”

“I would not let a rough fellow come near the children,” said Jim in gentle reproach.

“No—no. I am sure you would not. Then, pray keep your friend. I will help Frances to prepare something extra, and he shall be made welcome.”

“Thank you very much,” said Jim gratefully. “Tom has come to England for a holiday, and he is going to take lodgings in Exham for a few days, so that we may see something of each other. I should not wish him to come here, Mrs. Morland,” added Jim simply, “if you were afraid for the children; but, indeed, Tom is a nice fellow, and I think you will not dislike him.”

The last words proved true. Tom Lessing had not long been in Mrs. Morland’s presence before she had decided that she liked him very much. He was several years older than her stepson, and as big and strong as Jim was slight and active. He treated Jim’s “lady-folk” with courteous deference, and was evidently able to polish his “backwoodsman” manners for fit converse in an English home. The dinner passed off pleasantly, Jim and Austin distinguishing themselves as waiters. The visitor enjoyed everything, and behaved in an easy, natural fashion which had nothing vulgar about it. Mrs. Morland reflected that her stepson must have followed some wise instinct in the choice of his boyhood’s friends.

That dinner was the first of several meals shared by Tom with his old chum, and his chum’s kindred. Privately, he declared that Jim was a lucky chap to have proved his right to claim relationship with such a bright, plucky little pair as his lately-discovered brother and sister; and then he added a few words in acknowledgment of Mrs. Morland’s courteous welcome, which made Jim happier than anything. Besides sharing meals, Tom found himself made free of the smithy, where he held exhaustive discussions with Jim, and of the orchard, where he romped with Austin, to the latter’s great content.

During the old friends’ exchange of confidences and record of experiences, Jim was lured into expressions of feeling with regard to his kindred which made good-hearted Tom look on the lad with kindly and pitying eyes. With him, overwrought Jim felt he might venture to unbosom himself of his anxieties and ambitions concerning the future. Jim’s desired course of action tended in only one way—the proper maintenance, in ease and comfort, of his stepmother and sister, and the careful training of his brother with a view to Austin’s adoption of some honourable profession. While uttering his aspirations, Jim revealed to his attentive chum the reality of his pride in the girl and boy who depended on him, and his deep affection for them. Tom listened and pondered, and made up his mind. His liking for “young East” had always been something more than mere boyish comradeship; and the respect and sympathy with which he quietly noted Jim’s hard and continual effort to live up to his own high standard of duty now added to Tom’s former easy liking the deeper regard of his maturer years.

One morning Frances, wandering through the orchard for a breath of cool air, came suddenly on Jim, who was lying at full length on the bank in the shadow of the hedge, his head pillowed on his folded arms. There was something so forlorn in the lad’s attitude that Frances feared some fresh trouble had overtaken him; and she was not surprised that his face, when he raised it in answer to her call, was darkened by a deep dejection.

“Jim—Jim! What is the matter? Now, it’s no use to try to hide things, Jim! You know it isn’t. Just tell me.”

Jim dragged himself up to his sister’s level as she sat down beside him, and his eyes rested very wistfully on her inquiring face. So long and sad was his gaze that the girl grew yet more uncomfortable, and repeated her question insistently.

“I’ve no bad news for you, Missy,” said Jim at last, with great effort. “None that you will find bad, at least. I have heard something, and I’ve been thinking it over; that’s all. If I weren’t a coward, it wouldn’t have wanted any thinking.”

“Well, what is it, Jim?”

“I will tell you presently, Missy. As well now as any time; only I’d like your mother and the lad to hear too.”

“Jim,” said Frances, her brave voice quivering slightly, “you speak as though your news were bad.”

“That’s just my selfishness,” muttered Jim; “I couldn’t see all at once the rights of things. I can see now.”

“Come indoors and tell us all about it,” said Frances, trying to speak cheerfully; “not much news grows better by keeping.”

“It could be only a matter of hours for this, anyway,” replied Jim gently; “and if your mother is at liberty and Austin is at home, I will do as you wish.”

So Frances led the way, and the pair walked soberly to the little house which had become to both a cherished home.

Jim waited at the back-door while his sister went to look for her mother and brother, and finding them both in the study, sharing the window-seat, and the task of snipping gooseberries, ran back to summon the “head of the family”.

All the responsibility of headship was in the lad’s countenance as he entered the study in his sister’s wake. He stood silent while Frances, in brief fashion, explained the situation; but something in her stepson’s look caught and held Mrs. Morland’s attention, and made her suspect that a tragedy might underlie Jim’s unusual calmness. She could not guess how hard he had striven to reach the degree of composure necessary to satisfy his stepmother’s ideal of good breeding.

“Yes, I’ve something to tell,” he said, when Frances paused, “and I hope it will mean a real difference to you all. I had no right to look forward to such a chance as I have had given me, and I know you’ll wonder at it too—”

“James,” interrupted Mrs. Morland, with an acute glance, “you don’t look as though the chance were altogether welcome.”

“That’s what I told him,” said Frances brightly. “He pretends to bring good news, but I believe he’s a deceiver.”

Jim flushed slightly, and hung his head. “You must please forgive me,” he murmured, “if I seem ungrateful and selfish. Indeed, I want to see how everything’s for the best. I’ll be quick now, and tell my news. You know Tom Lessing has a fine place in Australia, and is making money fast. He has a lot of hands, and seems to pay them well; and he gives every one of them a share in his profits over and above their salaries. Tom is very kind, and—you’ve all been good and kind to him, for which we both thank you.”

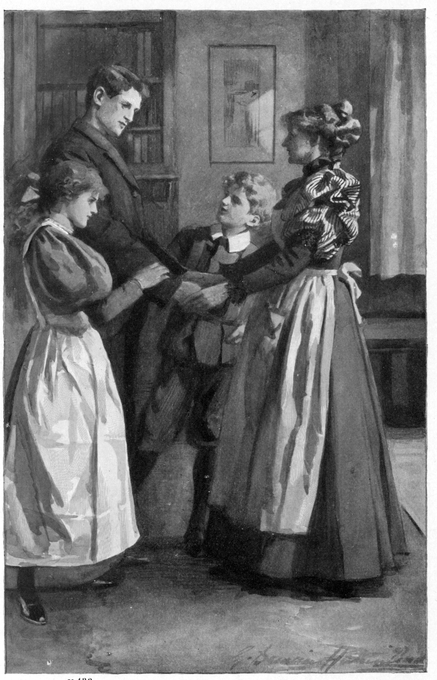

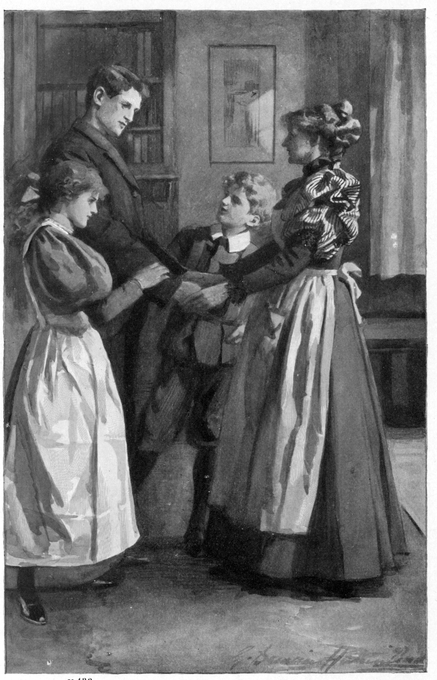

Though Jim spoke earnestly, there was an aloofness in his manner which touched all his listeners, and reminded them, with keen shame, what scanty cause he had, even now, to feel himself one of them. Frances impulsively moved a step nearer him, and stopped, overcome by the constraint she could not disguise; Austin sprang to his brother’s side, and pressed affectionately against him. Jim gently held him off, as though the lad’s caresses threatened his own self-control; but his hand kept the boy within reach, and once or twice passed tenderly over Austin’s tumbled curly head. If Mrs. Morland ever had doubted her stepson’s love for her children, the suspicion from that moment died away.

“Because he is kind, and because you have been good to him,” continued Jim, “Tom has given me a chance. He has offered to take me back with him to Australia, and to find me a good place as one of his overseers. He says I’d soon learn enough to be of use, and he’d help me to get on. I should have two hundred and fifty a year; and as I’d live with him, he’d give me board and lodging too. So, since I shouldn’t want much for clothes, I could send nearly all my earnings home; and there would be grandfather’s money as well, and we would sell the smithy. I’ve been thinking you might have a little house in Woodend, and the children would go to school again, and by and by Austin would go to college. I hope you would be very happy.”

The speaker’s lips trembled for just a second, in evidence of full heart and highly-strung nerves. Then Jim, with courageous eyes, looked across the room for comments and congratulations.

“We should be very happy?” queried Frances; and this time she went close to her brother, and took his hand. “Oh, Jim!” she exclaimed, her eyes bright with tears; “don’t go away from us, dear Jim!”

“You sha’n’t go away—so that’s all about it!” cried Austin, with a masterful toss of his fair head. “You sha’n’t oversee anybody, except us. It’s tommy-rot.”

“We are happy now,” continued Frances in trembling haste. “We don’t want any more money, if we can’t have it without giving you up to Australia. What’s the use of having found you, Jim, if you go away again?”

“AH! BUT YOU WOULD MAKE SUCH A MISTAKE IF YOU THOUGHT WE WOULD LET YOU GO.”

Boy and girl, on either side, were clinging tightly to him. Jim, trying to be calm—trying to be brave—looked desperately to his stepmother for her expected support. If she should quench Austin and Frances with some cynical reproof—if she should accept Jim’s final sacrifice with just a word of contemptuous indifference—surely his pride would help his judgment to keep fast hold of his failing courage.

Mrs. Morland had already risen, and was coming towards him now with hands outstretched, and in her face the light of a motherly love to which Jim could not try to be blind.

“Would you really do that for us?” she asked, smiling, though her voice was not quite steady. “Ah! but you would make such a mistake if you thought we would let you go. Frances is right;—we can do without wealth, but we can’t do without you!”