CHAPTER VII

THE WONDERFUL ANTENNÆ

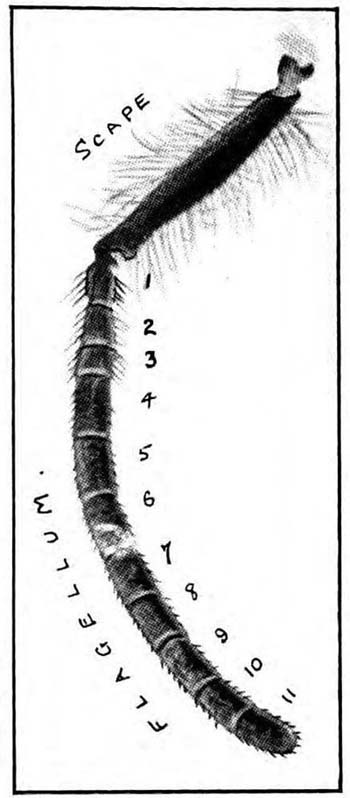

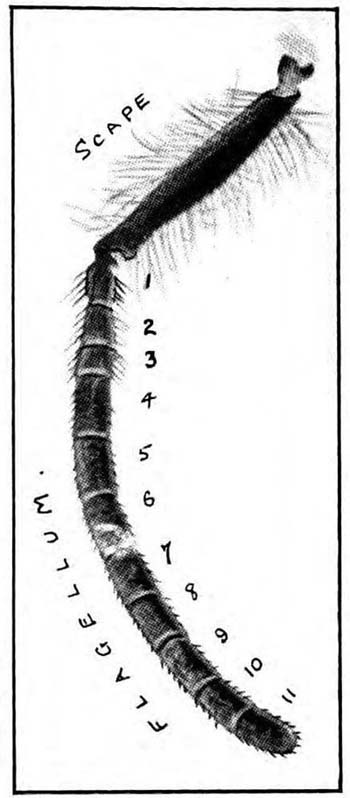

WONDERFUL as all the parts of the bee are, there are none so wonderful as the antennæ. This word comes from the Latin, and means horns or feelers, and the antennæ serve many purposes. In the hive, although all is dark, the bees are able to find their way about by means of them; they build the combs by their aid, and with them they communicate one with another. The antennæ are used, too, for the purpose of smelling, and curious to relate, the ears of the bee are situated in them. We generally expect to find the ears of living creatures in their heads, but in the insect world ears are found in many queer places. For instance, who would look for the ears of the cricket in one of its legs? yet this is where they are situated. This is not the only insect which has its ears in its legs, for those of the grasshopper are found in a similar position. Then there is a kind of shrimp, called the Mysis, and this creature actually has its hearing apparatus in its tail! And so, when we remember these peculiarities, the fact that the bee’s ears are situated in its antennæ is not so strange as it at first seemed. In (b) Plate VI. you will see the position the antennæ occupy on the worker bee’s head, whilst (a) Plate VII. will show you the feeler in detail. The antennæ of the worker bee each consist of a single long joint, and eleven small joints. The long joint is called the “scape,” meaning a shaft or stem, whilst the small ones are called the flagellum, a Latin word meaning “a little whip.” In (a) Plate VII. they have been numbered 1 to 11, as you will see. The antennæ of the drone, while resembling those of the worker, have one more small joint in the flagellum, thus making the total number twelve.

PLATE VII

(a)

Photo-micro. by] [E. Hawks

Antenna of Bee

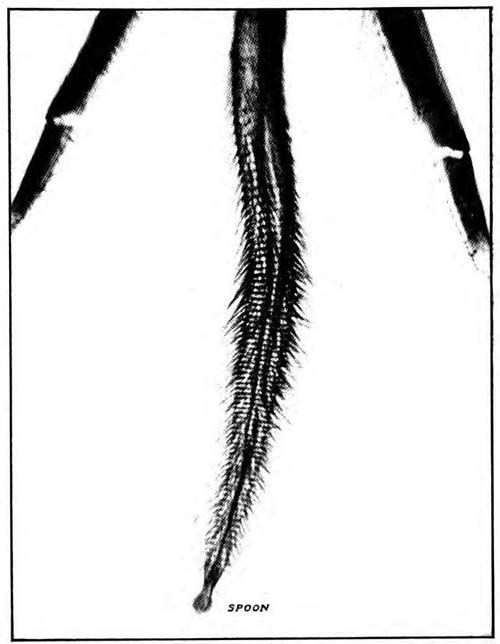

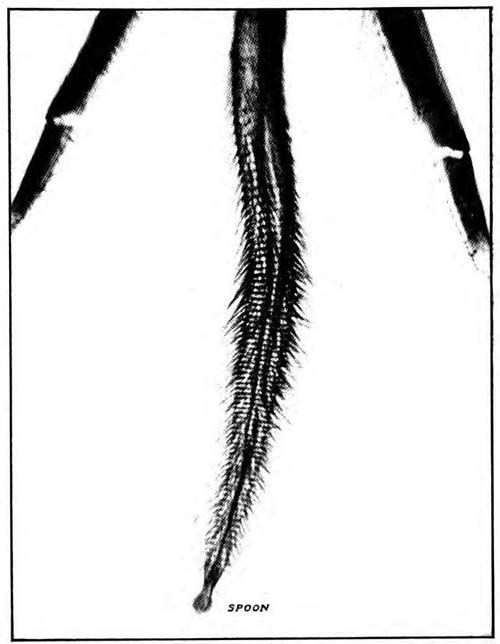

(b)

Photo-micrograph by] [E. Hawks

Tongue of Bee

The construction and movements of the antennæ closely resemble those of our own arms, the flagellum corresponding to the forearm, whilst the scape is like the upper part of the arm, between the elbow and the shoulder. Further than this, the antennæ are fixed to the head in much the same way as our arms are joined to our shoulders. This joint is called a cup-and-ball joint, and it enables the antennæ to be moved in practically every direction. In addition, each of the eleven joints of the flagellum is able to be moved separately; so you will see that a bee can very easily and quickly place its antennæ in almost any position.

On again looking at the plate, you will observe that the scape is covered by numerous hairs, which are both long and fine. The first three joints of the flagellum are also covered with hairs, which, however, are not like those of the scape, for they are much shorter and thicker. They look more like bristles, and all point in a downward direction. The remaining eight joints are covered with multitudes of still smaller hairs, and these again differ in their construction. To give you some idea of the complicated nature of the antennæ, I may tell you that the drone possesses over 2000 of these hairs on each one, whilst the worker has about 14,000. Each hair is connected with a nerve which is so delicate that the faintest touch of anything would be easily felt. The nerves are contained in the central part of the antennæ, which is hollow, and from there they lead to the ganglia. The bee can tell instantly the shape, height, and nature of any object by simply passing the antennæ over it. You know that if a person comes noiselessly behind you, say whilst you are reading, and lightly touches one of your hairs, you can feel the touch instantly. That is because each hair, like those of the bee, is connected with a nerve. You will easily understand, however, that the hairs and nerves of the bee are infinitely more sensitive than ours. It is necessary that the tiny workers should be provided with some means of doing things in the dark, for all the work of the hive has to be done under these conditions. The antennæ serve this purpose perfectly.

In a very powerful microscope it is found that the places between the hairs, in most of the antennæ joints at any rate, are covered with tiny oval-shaped holes and depressions. The nature and use of these holes are most difficult for us to understand, and it is not yet properly known for what they are really intended. In the first place, they are so very tiny that we can hardly imagine their size. They measure only about 1⁄10,000th part of an inch across, and each is surrounded by a minute ring of a bright orange colour. It is supposed, and I think it is quite probable, that by the aid of these holes the bee hears. There is not the slightest doubt that bees can hear, though at one time people had quite decided that they were perfectly deaf!

In addition to these little hearing holes, there are others called the “smell hollows”; they too are exceedingly numerous and minute. Each of the last eight joints of the worker bee’s antennæ is stated to have fifteen rows, and twenty smell hollows in each row! That is to say, there are over 2400 in each antenna. The queen has not quite so many, having, as a matter of fact, about 1600 on each; but the drone is possessed of the most of all, and his number reaches the astonishing figure of 37,000 hollows on each antenna. Every one of those hollows is a little nose, so that the bee’s power of smell must be very keen. What with the different kinds of hairs, so numerous and yet each with a separate nerve, the hearing holes, and lastly the smell hollows, you will, I feel sure, agree that the antennæ are most complicated, and you will understand why I call this chapter “The Wonderful Antennæ.”