CHAPTER VIII

THE EYES

THE same tiny head, which carries the marvelous antennæ, is provided with two large “compound” eyes, as they are called. If you are able to examine these eyes with a magnifying glass, you will at once see that they are lovely objects. The eye itself is of a deep purplish-black colour, and has an appearance which is rather difficult to describe. It seems almost as though it is covered with the finest satin, for it glistens in the sunlight.

The microscope shows that this appearance is due to the eye being composed of multitudes of six-sided cells, resembling, in fact, nothing so much as a piece of honeycomb. These cells are called facets, which means “little faces,” and each one measures about 1⁄1000th part of an inch in diameter. Over the surface of the eye are distributed numerous long, straight hairs; the chief purpose of these hairs is to protect the delicate facets, just as the eyelashes of our own eyes protect them. Bees have no eyelids, as we have, and so they have to rely upon these hairs to protect their eyes from dust and other such foreign bodies. The construction of the eye itself is wonderful to a degree, but it is also very difficult to understand, because it is so complicated and minute.

Each eye consists of a great number of facets, which are really smaller eyes, and this is the reason the eye is called compound. The eye of the worker contains over 6000 of them, and each one points in a slightly different direction. Large as this number may appear, it is less than half that possessed by the drone, whose facets actually number 13,000 in each eye. As a matter of interest, I may tell you that the queen bee has the least number of all, having but 5000. Each facet acts as a tiny lens. A lens, as you perhaps know, is something so shaped as to throw an image of the object to which it is directed. A camera has a lens of glass, and by the aid of this lens a picture can be taken of any object to which the camera is pointed. In that case the image of the object is thrown upon what is called a photographic plate. Our own eyes act as lenses, and throw an image of whatever we look at, not upon a photographic plate, but upon a sensitive surface called the retina. This word comes from the Latin, and means a “small net,” and it is a very good name, for the retina catches the picture from the pupil of the eye, and passes it on to the brain.

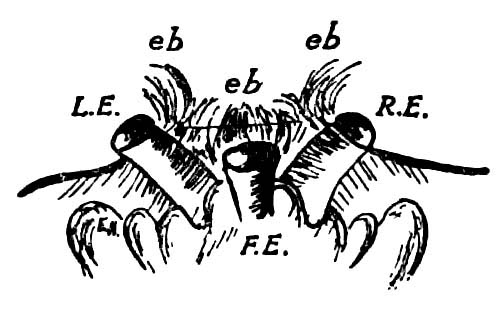

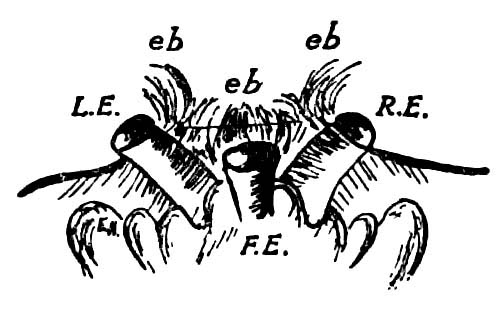

Although we might imagine that these compound eyes were sufficient for any purpose, yet we find that the bee has three more eyes; these are called the “simple” eyes. They are situated on the top of the head, and you may see one of them in (b) Plate VI. The other two are over the top of the head, for the three eyes are arranged in this manner ∵ so as to form a triangle. You will remember that the drone is furnished with a far greater number of facets than the worker. Consequently the compound eyes of the drone are much larger, and they not only take up the whole of the space at the sides of the head, but also extend right over the top, covering the position occupied by the simple eyes in the worker. Owing to this fact, the drone’s simple eyes are placed lower down, on the front of his head, their position corresponding pretty closely to the place our own eyes occupy. The simple eyes are so called because they do not seem to be nearly so complicated in their construction as the compound eyes, but the microscope shows that they also have an elaborate structure. If we were to cut open the front of a bee’s head, we should find that the simple eyes are set like this:—

You will notice that the two top ones (marked L. E. left eye and R. E. right eye) point in an outward direction, and it is by their aid that the bee can see sideways. The lower eye (F. E. front eye) is directed forwards, and with it things in front can be seen. The simple eyes are surrounded with tufts of hair (marked e. b. eyebrows), which are so placed that they do not interfere with the range of vision.

I must just tell you something of the uses of the five eyes. At one time it was supposed that each facet of the compound eyes made a separate image of the object to which it was directed. But this is very improbable, for what possible use could there be in the insect seeing, instead of the one flower at which it was looking, several thousands of flowers each exactly like the other? It is much more likely that every facet forms a picture of only that part of the object which is exactly in front of it, all the pictures combining to form a single image. No doubt the compound eyes are used for seeing things at a distance, and the simple eyes for objects near at hand.

It has been proved that bees can distinguish between colours, and even that they prefer certain colours to others; one of their favourite colours is pale blue. An experiment, which is both interesting and instructive, has often been performed, and it shows us that not only is the bee able to tell one colour from another, but also that it possesses a memory. Pieces of blue, yellow, and red paper are obtained, and upon each is placed a slip of glass. A little honey is placed upon the slip of glass which is over the blue paper, and all three are put near a hive. A bee is caught and placed on the honey. After sucking some of it she flies to the hive to store her treasure and quickly returns for more. She is allowed to make several journeys between the honey and the hive, so as to impress upon her memory that the honey is to be found on the blue paper. Then while she is away at the hive, the slip of glass is placed upon the yellow paper. She returns, as before, to the blue paper, and seems puzzled at not finding the honey there, but after a careful search, she discovers the honey on the yellow paper. The fact that the bee came back to the blue paper proves that she has a memory and that she is able to distinguish one colour from another.