CHAPTER IX

THE TONGUE AND MOUTH

PARTS

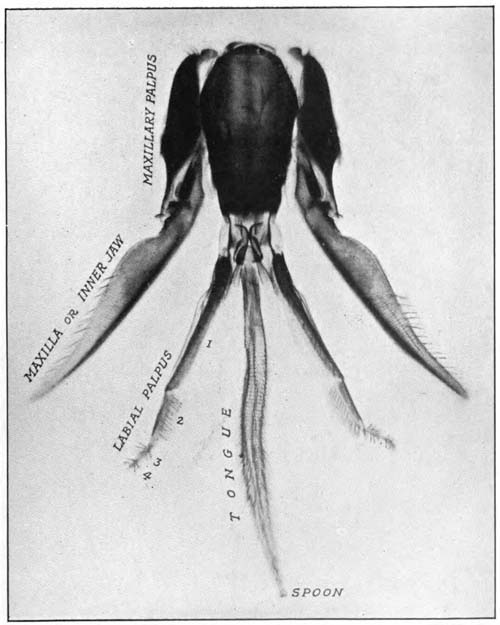

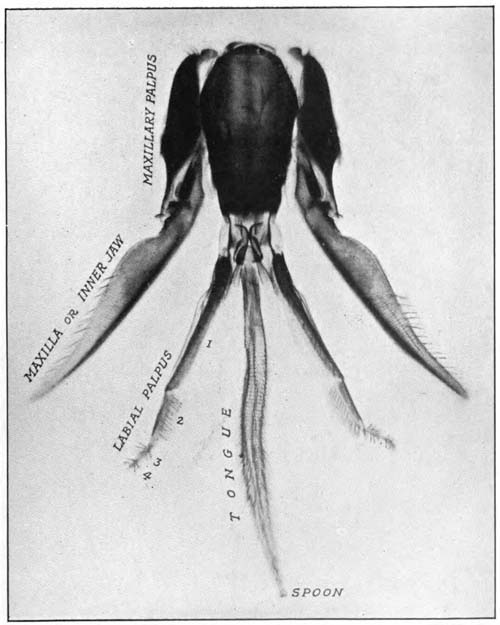

THE tongue of an insect is called the proboscis, a Greek word meaning a front feeder, or trunk, and indeed the bee’s tongue is not unlike the trunk of an elephant. Let us glance at Plate VIII., where a picture of the mouth parts of the bee is shown. The tongue itself is in the centre, and it appears long and hairy, tapering to a fine point. On each side of the tongue are the Labial palpi, which are part of the case in which the tongue is kept, when not in use. Beyond these are the Maxillæ, or inner jaws, which form the other part of the case.

Each labial palpus consists of four joints, the upper two (Nos. 1 and 2 on the picture) being much larger and broader than the lower ones, which are quite tiny in comparison. They have several hairs growing upon them, and these hairs are used for feeling. The importance of hairs to the bee is very great, and we find them all over the body. They are of different shapes and sizes, and we shall read more about them as we come to consider each kind in turn. When the labial palpi are closed, they protect the back part of the tongue, the front part being protected by the maxillæ. These four parts, when closed, make a kind of tube, in which the tongue rests. Although this protecting case cannot be drawn up into the mouth, the bee is able to draw up the tongue at will.

PLATE VIII

From a photo-micrograph by] [E. Hawks

Tongue and Mouth Parts of Bee

(b) Plate VII. shows a good view of the tongue itself, as seen with a high magnifying power. It is composed of a number of ring-like structures, and is covered with hairs which are regularly placed and point in a downward direction. The tongue of the worker bee, it is interesting to note, is nearly twice as long as that of the queen or of the drone. This is because neither of the latter gather nectar, and so they do not need such long tongues as the worker. Her tongue being longer, she is the more easily able to reach the nectar, which, in some flowers, is only to be found at the bottom of a long corolla. The tongue of the worker has from 90 to 100 rows of hairs, but those of the queen and the drone have only from 60 to 65 rows each.

The tongue is extremely elastic, and is capable of being moved in any direction at will. Some of the hairs with which the tongue is clothed are of use for feeling, but most of them are for a different purpose altogether. When a bee pushes her head into the corolla of a flower, her tongue sweeps from side to side. If there is any nectar there, it sticks to the hairs of the tongue in tiny droplets, and in this way it is collected. Later on we shall find how it is dealt with after it has been gathered.

On (b) Plate VII., at the very tip of the tongue, there is to be seen a small object like a spoon. This is indeed its name, and it is used for collecting the most minute quantities of nectar. It is covered with a number of tiny hairs, some of which are split into several branches.

From this description you will see that a bee’s tongue is very fully equipped for gathering small, as well as large, quantities of nectar. Even the tiniest drop is carefully treasured, for the bees know that “every little helps.”