CHAPTER XIX

THE ANCIENTS AND BEES

BEFORE we go on to consider the habits of the bees, I think you will be interested to hear something about their early history, and how they used to be kept in bygone ages. Thus we shall be able to trace the progress of bee-keeping from its earliest sources to the present day, and to realise the wonderful improvements of modern methods upon those of the ancients.

It is not possible for us to tell with any certainty when bee-keeping actually commenced, but it has a very ancient origin. No doubt for ages past it has been the custom of men to obtain honey from the store of wild bees. For instance, we read in the Bible that John the Baptist lived for some time in the wilderness on locusts and wild honey. The earliest records in existence show us that the Egyptians kept bees in some kind of hive, and that they carefully studied their habits. If you visit the Egyptian rooms at the British Museum, you may perhaps see the sarcophagus which contains the mummified remains of a great king, called Mykernos. This coffin dates back to 3633 years B.C., and Mykernos was at that time the King of Lower Egypt. On the outside of the coffin is a peculiar drawing, or hieroglyphic as it is called. It is something like this:—

This funny little figure represents a bee, for at that time it was thought that the bees were ruled over by a king-bee, which the Egyptians knew to be larger than all the others. Because the bees always appeared to be so happy under their king, the Egyptians thought it would be a good symbol to place on the coffin of their ruler. This is the very earliest known record relating to bees, but we know now, of course, that the large bee, which seemed to the Egyptians to rule the others, is not a king but a queen.

Those of you who learn Latin may some day have to translate some books called the Georgics. They were written by a clever man called Virgil, and although schoolboys do not always like them, yet they are most interesting, especially the Fourth Book, which tells us a great deal about bees. Virgil lived in a town called Parthenope, which we now know as Naples. He was a great bee-keeper, and was never tired of watching his bees at their work, and moreover he left very accurate accounts of his observations. Hives in those days were dome-shaped, and made from pieces of bark stitched together, or sometimes of osiers or plaited willows. We can imagine the learned Virgil walking in his garden, surrounded by sweet-smelling flowers and herbs, and by his quaint bee-hives. Below, down the mountain side, lay “sweet Parthenope,” as he called it, with its orange and lemon groves. Beyond the town lay the most beautiful bay in the world, the Bay of Naples, whose water, as blue as turquoise, shimmered in the summer sun. Over all stood the crater of mighty Vesuvius, from the cone of which a thin wisp of smoke hung lazily in the atmosphere. In this way Virgil spent many happy days, and in the book I have mentioned we may read of his doings, and of his bees. Most of his ideas about bees were false, but some of the rules which he laid down for bee-keeping hold good even at the present time.

Up to the time of Virgil, and even later, the duties of the workers in the hive were not properly understood. It was not known even that the largest bee was really the mother of them all, and that the workers looked after and tended the eggs, which later on would develop into young bees. In the days of Virgil it was supposed that bees were born in flowers, or that if an ox was killed and left to decay, a swarm of bees would be formed in its body and could then be put into a hive. In the Fourth Georgic very careful instructions are given by Virgil as to how to prepare an ox for this purpose. Many years ago this was translated into our language by a bee-keeper, and the wording is so quaint that I think you will be interested to read the following extract from the curious directions. We are told that we must find “a two-year-old bull calf, whose crooked horns be just beginning to bud. The beaste, his nose-holes and breathing are stopped, in spite of his much kicking! After he hath been thumped to death, he is left in the place, and under his sides are put bits of boughs and thyme and fresh-plucked rosemarie. In time the warm humor beginneth to ferment inside the soft bones of the carcase, and wonderful to tell there appear creatures, footless at first, but which soon getting unto themselves wings, mingle together and buzz about, joying more and more in their airy life. At last they burst forth, thick as raindroppes from a summer cloude....”

The supposition that bees were obtained from a dead ox lasted right down to the seventeenth century, and there is no doubt that the Egyptians believed in this too, for in some of their records we find that they buried the body of an ox, leaving the horn-tips just above the soil. After it had been left so for about a week, the tips of the horns were sawn off, and a swarm of bees issued, like smoke from a chimney. What a foolish idea this was, just as though the body of an ox could, in any manner imaginable, change into a swarm of bees! It probably originated in the fact that the decaying body of an ox or other animal quickly becomes surrounded by swarms of flies, wasps, and other insects.

Up to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the people had no other substance than honey with which to sweeten their food, for the mode of extracting the sweet juice contained in the sugar-cane was not known till later. Sugar-cane was actually discovered somewhere about the first century A.D. and a learned writer, Strabo by name, has told how the chief admiral of the fleet of Alexander the Great found what he called “a wonderful honey-bearing reed,” whilst on a voyage of discovery to India. It was not until the fifteenth century, however, that the Spaniards set up a sugar plantation in Madeira, and extracted the juice from the cane: even then it was only the rich people who could afford the new luxury, and others had still to use honey. From these remarks, then, we can easily understand how necessary bees were to the people, and how much depended on a good honey year.

Besides using honey for sweetening purposes, the Anglo-Saxons made from it a drink called Mead. You have no doubt read of this in your history books, but perhaps you did not know that it was made principally from honey. Sometimes the juice of mulberries was added to it, to give the drink a flavour, and it was then called Morat. People who could afford to do so flavoured it with spices, or sometimes even added wine, and in this form it was used in the royal palace. In some country places old-fashioned people still make and drink mead, but it is very rarely heard of nowadays.

Bees also provided the ancients with wax, from which a sort of candle was made, for in those times there was no electricity or even gas, and so the people were very glad to be able to use the wax for lighting purposes. Nowadays, beeswax, mixed with a little turpentine, is used for polishing furniture and oilcloth.

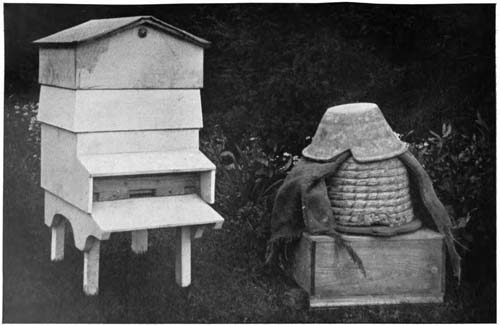

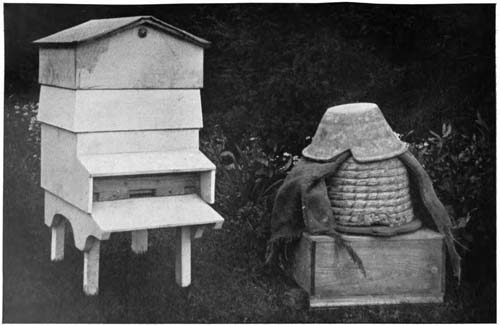

PLATE XIV

The New and the Old