CHAPTER XX

THE HIVE

A HIVE may with all truth be called a bee-city, for in it there live thousands upon thousands of little workers. In this chapter I hope to tell you about the actual construction of this wonderful city, so that you may understand more easily the chapters that will follow.

Hives used to be made of straw, and were called “skeps.” Some of these skeps may still be seen in country places, but they are rapidly being superseded by the more convenient wooden hive. The two kinds are shown in Plate XIV. The wooden hive is a kind of box made in a special way, and it is usually painted white, for this not only looks clean but also keeps out the heat of the summer sun. You will notice that, like one of our own houses, it is divided into three storeys. Close to the floor of the hive, at the bottom of the lowest storey, is the door, and this is made by cutting a slit in the wooden wall. Two little slips of wood slide in front of it, so that it can be made narrower, or even completely closed at the wish of the bee-keeper. If the bees themselves wish to close up the entrance for any reason, they are able to do so by blocking it up with wax. The top chamber of all is the roof, which is empty, and serves to protect the hive from the rain. It must, of course, be lifted off by the bee-keeper each time he wishes to look into the hive. The second chamber is a sort of extra storehouse, and it is used by the bees to store honey when the third chamber is full. This third chamber is the most important of all, for it is here that the bees live. It consists of rows upon rows of combs, some of which are storeplaces for honey, but the greater part form the nurseries where the young bees are brought up.

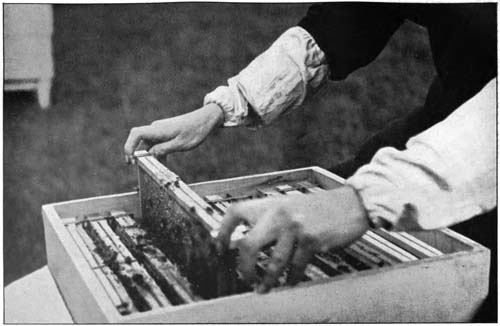

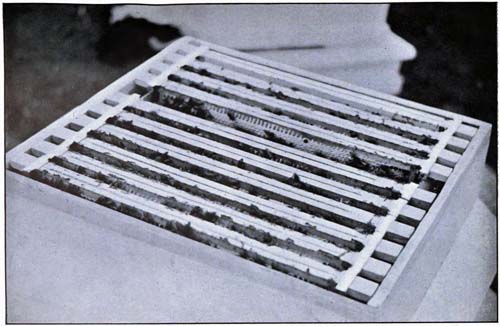

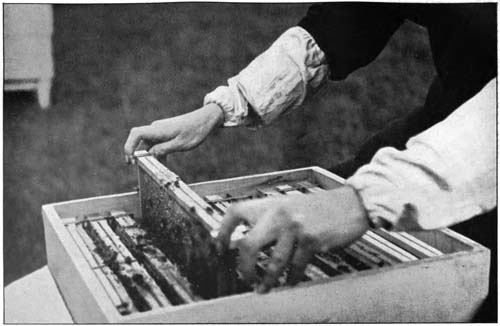

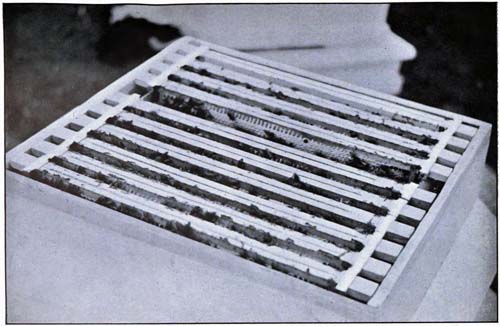

All the cells are built of wax, no matter whether they be honey cells or cradles, and they are constructed in wooden frames which the bee-keeper places in the hive for the purpose. In Plate XV. we see the roof and the second chamber removed, exposing the inside of the bottom chamber. The bee-man in the picture is lifting out one of these frames of combs in order to examine it. The frames are simply four pieces of wood, and are used so that the bees may not fasten their combs to the walls of the hive, for if this were done it would not be possible for us to remove them from the hive. The number of frames a hive contains depends on the size and prosperity of the bee-city, and also on the particular time of the year. If the city is a large one, and the inhabitants numerous, there may be twelve or fourteen frames, each containing thousands of separate cells. On the other hand, if the bees are few, or suffering from any disease, the frames may be reduced to half this number. Of course, the more numerous the frames, the greater is the amount of work to be done, and the more workers will be required to attend to the young bees, and to the duties of the hive. When all the frames are in position, they look something like the picture in Plate XVI.

PLATE XV

Lifting out a Frame of Comb

PLATE XVI

From a photograph by] [E. Hawks

Showing the Frames in Position

When we are examining a frame, we generally cover the others over with a cloth, for the bees do not like the light to penetrate their city. The frame having been replaced and the second chamber put on, we cover all over with thick pieces of felt to keep the hive warm, and on top is placed the roof. The hive stands on four legs, a few inches above the level of the ground, and the door is generally sheltered by a kind of porch. In front of the door there is a board which projects a few inches, and this is called the alighting-board. On it the bees settle when returning from the fields, and from it they commence their flight when leaving the hive.