CHAPTER XXV

THE COMB BUILDERS

IN order to trace the history of a hive, and to learn about the round of work which goes on day by day, we will suppose that a swarm of bees has been placed in an empty hive. We shall then be able to follow them as they commence with the first necessary work of building the combs. Our later chapters will lead us through the whole cycle of hive life.

We have already seen how the frames are placed within the hive, but we have yet to learn how the combs are built in them. Before the builders can set to work, however, it is necessary that the wax, of which the combs are constructed, should be made.

When a swarm of bees first enters the empty hive, numbers of them climb to the roof, and fasten themselves, by means of their tiny claws, to points of vantage. Other bees then join them, each hooking its claws in the claws of another, and in this manner chains of living bees hang from the roof in festoons. As time goes on these chains become more numerous, until the hanging bees look like a large cluster, for the chains cross and intertwine. All the bees do not form themselves into chains, for guards are posted at the hive door, while others examine every corner of their new home. The scavengers have to clean the floor and carry away twigs or gravel, so that everything shall be perfectly tidy for the builders to start work.

Now commences that wonderful and mysterious process of wax forming, which is carried on in perfect silence by the cluster of hanging bees. You will remember that the abdomen of the worker is composed of six rings; underneath these are the eight wax-pockets. There are two in each ring except in the first and last. It is perhaps interesting to note that the queen and the drone have no wax-pockets because they do not take part in the making of wax. For a similar reason their legs are not furnished with wax-pincers, like those of the worker. As the bees hang from the roof of the hive, in solemn and impressive silence, tiny scales are to be seen protruding from the wax-pockets. They look almost like a letter which has been pushed half-way into the slot of a pillar-box. A wax-pocket produces one wax scale, and so the workers each make eight tiny pieces of wax. In order that wax may be made in this manner it is necessary for the bees to consume a large quantity of honey, 10 or 15 lbs. of which produces only 1 lb. of wax.

We have already seen that the hind leg of the worker is provided with a set of wax-pincers (see Plate X.), and when the tiny scale of wax has been formed, these pincers take hold of it and remove it from the pocket. By means of the front legs it is then passed to the mouth, and here the strong little jaws come in useful. In its present state the wax is hard and rough, and it must be made smooth and pliable. It is mixed with juices supplied by glands in the bee’s mouth, and worked by the jaws until it is so soft that it can be moulded into any desired shape. Often, when wax is being made, the floor of the hive becomes covered with wax plates which have fallen from the cluster above. When the wax has been kneaded to the correct degree of softness, the worker will leave the cluster of hanging bees, and crawl to the highest part of the roof of the hive. This is the foundation-stone of the combs, for they are not built upwards from the ground as our houses are, but downwards from the roof.

PLATE XX

From a photograph by] [E. Hawks

Queen Cells on Comb

When the first plate of wax is in position, the little worker will take the other plates one by one from her wax-pockets, and knead them as she did the first. Each in turn will be placed on the foundation, and then the bee will again join the cluster. Immediately she disappears, however, her place will be taken by another, who goes through exactly the same process. She in turn will be followed by another, and so on, until a small piece of beautiful white wax hangs from the roof. At this stage it is time for the architects to plan out the position and shape of the first cells, which are to be sculptured out of the wax. If we watch, we may see one of these bees appear, and it is evident that she knows exactly what to do, and just what shape the first cell is to be. She moulds the unformed wax by means of her jaws, and very soon the outline of the cell is seen. It is hollowed out, and the wax removed in this process is carefully placed so as to form the walls. Meanwhile, another architect has been doing a similar thing on the opposite side of the piece of wax, for the cells are built back to back, as by this arrangement there is a saving of material. The wax-makers continue to add more and more wax, the sculptors go on with their work, and soon the form of the comb becomes apparent.

CRADLE CELLS.

HONEY CELLS.

I suppose every one knows that bee cells are hexagonal, or six-sided. If they were made circular, you can easily understand that there would be a great deal of space and material wasted, for the spaces between the cells would need to be filled up. Then, again, if they were made diamond-shaped, there would still be places to fill in. It is true they might be made four-sided, but apart from the fact that such cells would not be strong enough, it is not possible for them to be made thus, for the angles would be too great for the bees to get their jaws into the corners. It has been found that six-sided cells are the strongest and the most economical, but how the bees found this out, too, is a mystery.

There are three kinds of bee cells: firstly the cradle cells, in which the young bees are reared. They are 1⁄2 inch deep and 1⁄5th inch in diameter. There will therefore be about twenty-eight in a square inch of comb, but as the drone is slightly larger than the worker, his cradle must be bigger. We find accordingly that the drone cells are 1⁄4th inch in diameter, or about eighteen to the square inch.

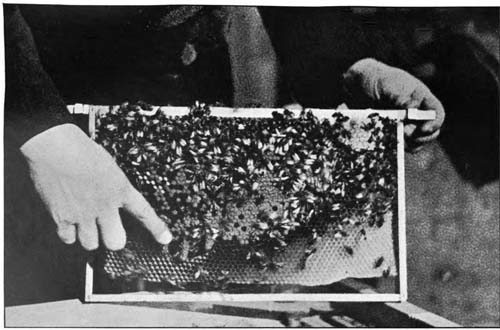

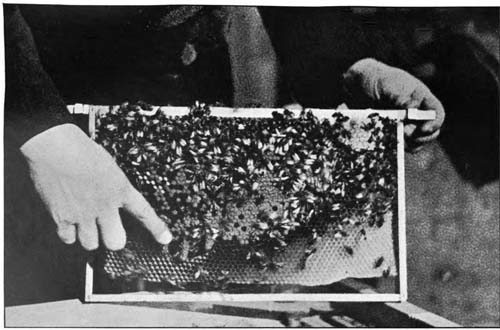

Then there are the royal cells, which are altogether different. In them the young queens are reared, and in appearance they are something like acorn cups. In Plate XX. you see a picture of a frame of comb, taken from the hive with the bees still on it. The bee-man is pointing to two of these queen cells, and you will see that they hang downwards, in a place where the ordinary comb has been cut away to make room for them.

Lastly there are the honey cells, which are of the same size as the cradle cells, but instead of being built horizontal they are made sloping upwards. By constructing them in this way honey stored in them is prevented from running out over the combs.

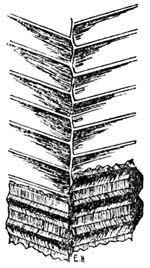

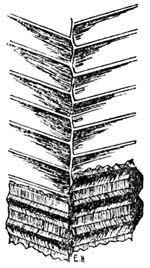

The back of the cells, or the dividing wall between the two sets, is not flat, as we might imagine. If you look at the sketches you will see that the cells are fitted into one another so cleverly that the bottom of one cell forms half of the bottoms of two cells of the other side of the comb. All the cells of one sort, say for instance the honey cells, are made exactly the same size, and do not differ by the fraction of an inch. How the bees are able to measure the width when building them is a mystery. Perhaps the antennæ have some important part to play in this matter, but if so it has yet to be discovered. Another thing which is as curious as it is mysterious is how the sculptors on each side of the comb are able to fit in the cells so neatly that each one is in its right place with regard to the cells on the other side of the dividing wall. It is certain that the workers cannot see through the wall of wax, and yet the two lots of cells correspond exactly.