CHAPTER XXVI

THE LIFE OF THE BEE

ALL the time the cells are being built the queen wanders about the hive in a distracted fashion, because there are no cells ready for her to fill. Now that some are ready, however, her movements change. Surrounded by her councillors, or ladies-in-waiting, as we might call them, she clambers over the comb and selects a cell in which to lay the first egg. She very carefully examines the cell by placing her head in it and feeling the sides with her antennæ. Being satisfied that it is in a fit state to become the cradle of a young bee, she withdraws her head and then the egg is laid. All this time the ladies-in-waiting stand round, and in the season for egg-laying you may quickly pick out the queen by the circle of bees about her (see Plate III.). They guide her over the comb, feed and clean her; sometimes, too, we may see them stroking her very tenderly with their antennæ. After the first egg is deposited in the cell, the queen moves to the next, and so on all through the summer. During this time she lays day and night, and does not appear to sleep.

The eggs are little pearly-looking objects something like tiny rice grains, and each one is fastened to its cell by a drop of gummy liquid.

In the meantime the bees are at work building combs with all haste, for the queen is close on their heels, demanding more and more cells. She does not rest until the whole of the ten or twelve frames have been completely filled with cells and eggs. By this time the first eggs which were laid will have hatched out into young bees, who will leave their cradles to take part in the duties of the hive. These first cells will then be cleaned out by the scavengers, and the queen will lay more eggs in them. In this way the queen goes on all the summer, and as a matter of fact, if the hive be a prosperous one, she may lay as many as 3000 eggs each day! After the eggs have been laid the queen does not appear to take the slightest interest in what may become of them. On the other hand, the worker bees do, for they know that on these tiny little eggs depends the future of the hive.

In three or four days an egg will hatch into a tiny white grub, which the nurse bees immediately commence to feed. It is not fed upon honey, though, for that would be like feeding a baby on roast beef! The nurse bees have certain glands in their bodies by which they are able to turn honey into a kind of bee-milk, and this is called “chyle food.” For three days the little grub is carefully fed upon this preparation, and then it is given “modified chyle food,” as it is called, which is also bee-milk, but richer than before. During these few days the grub casts its skin and grows very quickly, until on the fifth day it turns into a chrysalis, just as a caterpillar does before becoming a butterfly. The bee-grub spins a soft silken cocoon, and the sculptor bees come along and seal over the mouth of the cell with a cover, which admits air so that the grub may breathe.

The grub then commences what is called its metamorphosis—a Greek word meaning “a change of form”—and a wonderful change it is. In sixteen days from the time that the cell was closed up, the fat little grub turns into a perfect worker, just like a caterpillar changes into a butterfly. The young bee is now ready to emerge from her cell, and the porous capping is the only barrier. The little prisoner, however, finds that she has a sharp pair of jaws and so begins to bite the capping. Slowly it is all snipped away, and we see a tiny hole appear, which grows larger and larger. In a few moments out comes one of the antennæ, and waves about as though to explore the world beyond the cell. It seems to give a good report to the little bee, for the biting of the cap is redoubled, and before long, assisted perhaps by some of the nurse bees, the youngster slowly emerges. She is, however, very pale and weak as yet, and so the nurse bees commence to clean and feed her. She soon gains sufficient strength to take an interest in what is going on around, and we may imagine that she is somewhat surprised to find how busy is the city into which she has stepped—every one rushing here, there, and all over, none seeming to take any notice of the young bee, and everybody apparently having something to do, and to be in a great hurry to do it!

A fortunate insect is the little bee, none the less; for she has no need to attend school or to have any lessons. She knows all that she need know as soon as she is born. In a few hours’ time, for instance, she will be feeding grubs, just as she was fed by other bees some days before. She will know all about the city, the duties which she has to perform, and the respect which she must pay to the queen, her mother. After perhaps a fortnight or so of nurses’ work she will join the ranks of the foragers, and seek the nectar of the sweet-scented flowers.

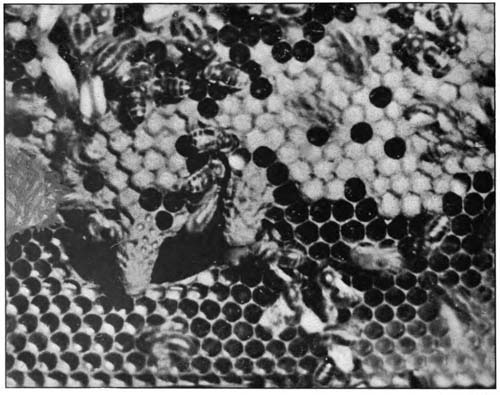

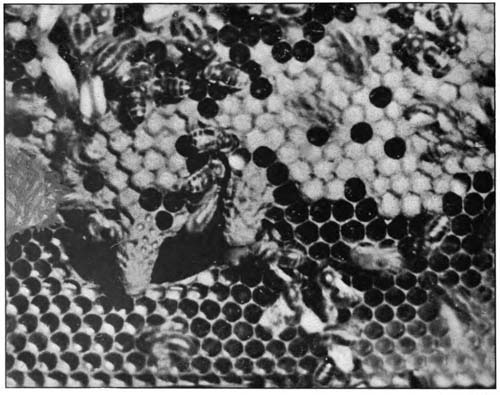

PLATE XXI

From a photograph by] [E. Hawks

Queen Cells

This, then, is the history of the birth of a worker bee, of which a prosperous hive may contain anything from 30,000 to 60,000. The history of the birth of a drone is practically the same, except that in his case it takes twenty-five days for the egg to change into the complete insect.